Imagine that you’ve always considered your own beliefs to be somewhere in the political center. Maybe a little to the left. Now imagine that, in the space of two years, your country’s politics have shifted so radically that you find yourself on the “Reactionary Right”, on the way to execution by your government.

And your personal convictions have never changed.

America’s strongest Revolution-era ally lost its collective mind in 1792, when France descended into a revolution of its own. 17,000 Frenchmen were officially tried and executed during the 1793-94 “Reign of Terror” (la Terreur) alone, including King Louis XVI himself and his queen, Marie Antoinette. Untold thousands died in prison or without benefit of trial. The monarchical powers of Europe were quick to intervene. For the 32nd time since the Norman invasion of 1066, England and France once again found themselves at war.

France had been the strongest ally the Americans had during the late revolution, yet the United States remained neutral in the later conflict, straining relations between the former allies. Making matters worse, America repudiated its war debt in 1794, arguing that it owed the money to “l’ancien régime”, and not to the French First Republic which had overthrown it, and executed its King.

By this time, Revolution-era America’s most important French allies were off the stage, the Comte de Grasse dead, the Marquis de Lafayette and the Comte de Rochambeau languishing, in prison.

Both sides in the European conflict seized neutral ships which were trading with their adversary. The “Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation” with Great Britain, ratified in 1795 and better known as the “Jay Treaty”, put an end for now to such conflict with Great Britain, but destroyed relations with the French Republic.

French privateers cruised the length of the Atlantic seaboard preying on American merchant shipping, seizing 316 civilian ships in one eleven-month period, alone.

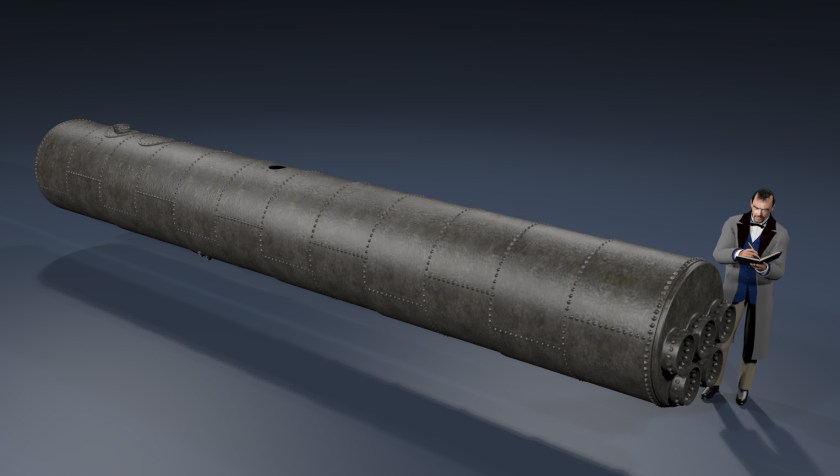

At this point, the United States had virtually no means of fighting back. The government had disbanded the Navy along with its Marine contingent at the end of the Revolution, selling the last warship in 1785 and retaining only a handful of “revenue cutters” for customs enforcement. The Naval Act of 1794 had established a standing Navy for the first time in American history and begun construction on six heavy frigates, the first three of which would launch in 1797: the USS United States, USS Constellation, and USS Constitution.

In 1796, France formally broke diplomatic relations with the United States by rejecting the credentials of President Washington’s representative, Ambassador Charles Cotesworth Pinckney.

The following year, President John Adams dispatched a delegation of two, with instructions to join with Pinckney in negotiating a treaty with France, on terms similar to those of the Jay treaty with Great Britain.

These were the future Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Marshall, and future Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry, a man who later became the 5th Vice President and lent his name to the term “Gerrymander”.

The American commission arrived in Paris in October 1797, requesting a meeting with French Foreign Minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand. Talleyrand, unkindly disposed toward the Adams administration to begin with, demanded bribes before meeting with the American delegation. The practice was not uncommon in European diplomacy of the time, but the Americans refused.

Documents later released by the Adams administration describe Nicholas Hubbard, an English banker identified only as “W”. W introduced “X” (Baron Jean-Conrad Hottinguer) as a “man of honor”, who wished an informal meeting with Pinckney. Pinckney agreed and Hottinguer reiterated Talleyrand’s demands, specifying the payment of a $12 million “loan” to the French government, and a personal bribe of some $250,000 to Talleyrand himself. Met with flat refusal by the American commission, X then introduced Pierre Bellamy (“Y”) to the American delegation, followed by Lucien Hauteval (“Z”), sent by Talleyrand to meet with Elbridge Gerry. X, Y and Z, each in their turn, reiterated the Foreign Minister’s demand for a loan, and a personal bribe.

Believing that Adams sought war by exaggerating the French position, Jeffersonian members of Congress joined with the more warlike Federalists in demanding the release of the commissioner’s communications. It was these dispatches, released in redacted form, which gave the name “X-Y-Z Affair” to the diplomatic and military crisis which followed.

American politics were sharply divided over the European war. President Adams and his Federalists, always the believers in strong, central government, took the side of the Monarchists. Thomas Jefferson and his “Democratic-Republicans” found more in common with the liberté, égalité and fraternité espoused by French revolutionaries.

In the United Kingdom, the ruling class appeared to enjoy the chaos. A British political cartoon of the time depicted the United States, represented by a woman being groped by five Frenchmen while John Bull, the fictional personification of all England, looks on in amusement from a nearby hilltop.

Adams’ commission left without entering formal negotiations, their failure leading to a political firestorm in the United States. Congress rescinded all existing treaties with France on July 7, 1798, the date now regarded as the beginning of the undeclared “Quasi-War” with France.

Four days later, President John Adams signed “An Act for Establishing and Organizing a Marine Corps,” permanently establishing the United States Marine Corps as an independent service branch, in order to defend the American merchant fleet.

Talleyrand himself raised the stakes, saying that attacks on American shipping would cease if the United States paid him $250,000 and gave France 50,000 pounds sterling and a loan for $100 million. At a 1798 Philadelphia dinner in honor of John Marshall, South Carolina Congressman Robert Goodloe Harper’s toast, spoke for the American side: “Millions for defense but not one cent for tribute.”

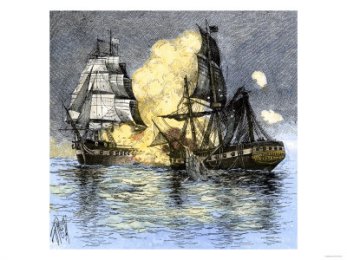

America’s “quasi-war” with France, begun this day in 1798, would see the first combat service of the heavy frigate USS Constitution, better known as “Old Ironsides” and today, the oldest commissioned warship in the world, still afloat. The undeclared war would be fought across the world’s oceans, from the Atlantic to the Caribbean, to the Indian Ocean, and the Mediterranean Sea.

The Convention of 1800 ended the Quasi-War on September 30, nullifying the Franco-American alliance of 1778 and ensuring American neutrality in the Napoleonic wars. $20,000,000 in American “Spoliation Claims” would remain, unpaid.

For the United States, military escalation proved decisive. Before naval intervention, the conflict with France resulted in the loss of over 2,000 merchant ships captured, with 28 Americans killed and another 42 wounded. Military escalation with the French First Republic cost the Americans 54 killed and 43 wounded, and an unknown number of French. Only a single ship was lost, the aptly named USS Retaliation, and that one was later recaptured.

Indeed, such a system has imperfections, not least among them those who would ascend to political office.

Indeed, such a system has imperfections, not least among them those who would ascend to political office.

Humphreys then used a hailing trumpet and ordered the American ship to comply, to which Barron responded “I don’t hear what you say”. Humphreys fired two rounds across Chesapeake’s bow, followed immediately by four broadsides.

Humphreys then used a hailing trumpet and ordered the American ship to comply, to which Barron responded “I don’t hear what you say”. Humphreys fired two rounds across Chesapeake’s bow, followed immediately by four broadsides.

United States Naval Captain James Lawrence was eager to comply, confident in the wake of a number of American victories in single-ship actions.

United States Naval Captain James Lawrence was eager to comply, confident in the wake of a number of American victories in single-ship actions.

CSS Alabama steamed out of Cherbourg harbor on the morning of June 19, 1864, escorted by the French ironclad Couronne, which remained nearby to ensure that the combat remained in international waters. Kearsarge steamed further to sea as the Confederate vessel approached. There would be no one returning to port until the issue was decided.

CSS Alabama steamed out of Cherbourg harbor on the morning of June 19, 1864, escorted by the French ironclad Couronne, which remained nearby to ensure that the combat remained in international waters. Kearsarge steamed further to sea as the Confederate vessel approached. There would be no one returning to port until the issue was decided. Captain Winslow put his ship around and headed for his adversary at 10:50am. Alabama fired first from a distance of a mile, and continued to fire as the range decreased.

Captain Winslow put his ship around and headed for his adversary at 10:50am. Alabama fired first from a distance of a mile, and continued to fire as the range decreased.

Boston was all but an island in those days, connected to the mainland only be a narrow “neck” of land. A Patriot force some 20,000 strong took positions in the days and weeks that followed, blocking the city and trapping four regiments of British troops (about 4,000 men) inside of the city.

Boston was all but an island in those days, connected to the mainland only be a narrow “neck” of land. A Patriot force some 20,000 strong took positions in the days and weeks that followed, blocking the city and trapping four regiments of British troops (about 4,000 men) inside of the city.

A group of Machias men approached Margaretta from the land and demanded her surrender, but Moore lifted anchor and sailed off in attempt to recover the Polly. A turn of his stern through a brisk wind resulted in a boom and gaff breaking away from the mainsail, crippling the vessel’s navigability. Unity gave chase followed by Falmouth.

A group of Machias men approached Margaretta from the land and demanded her surrender, but Moore lifted anchor and sailed off in attempt to recover the Polly. A turn of his stern through a brisk wind resulted in a boom and gaff breaking away from the mainsail, crippling the vessel’s navigability. Unity gave chase followed by Falmouth.

Perhaps the man was ill at the time but, be that as it may, the die was cast. The conspirators now needed only the right set of circumstances, to put their plans in motion.

Perhaps the man was ill at the time but, be that as it may, the die was cast. The conspirators now needed only the right set of circumstances, to put their plans in motion.

“…Venturing still farther under the buried hulk, he held tenaciously to his purpose, reaching a place immediately above the other man just as another cave-in occurred and a heavy piece of steel pinned him crosswise over his shipmate in a position which protected the man beneath from further injury while placing the full brunt of terrific pressure on himself. Although he succumbed in agony 18 hours after he had gone to the aid of his fellow divers, Hammerberg, by his cool judgment, unfaltering professional skill and consistent disregard of all personal danger in the face of tremendous odds, had contributed effectively to the saving of his 2 comrades…”.

“…Venturing still farther under the buried hulk, he held tenaciously to his purpose, reaching a place immediately above the other man just as another cave-in occurred and a heavy piece of steel pinned him crosswise over his shipmate in a position which protected the man beneath from further injury while placing the full brunt of terrific pressure on himself. Although he succumbed in agony 18 hours after he had gone to the aid of his fellow divers, Hammerberg, by his cool judgment, unfaltering professional skill and consistent disregard of all personal danger in the face of tremendous odds, had contributed effectively to the saving of his 2 comrades…”.

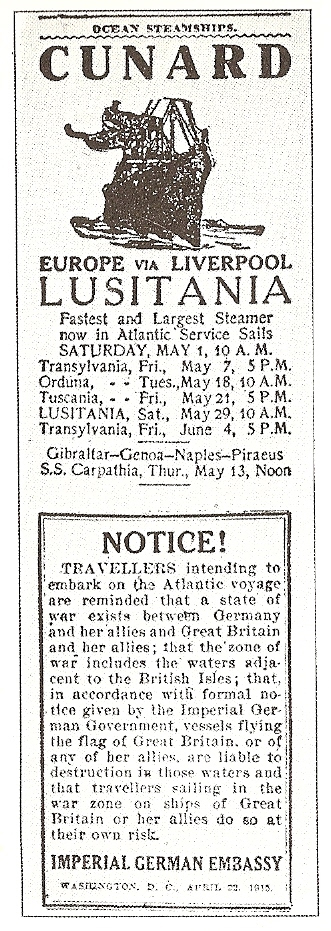

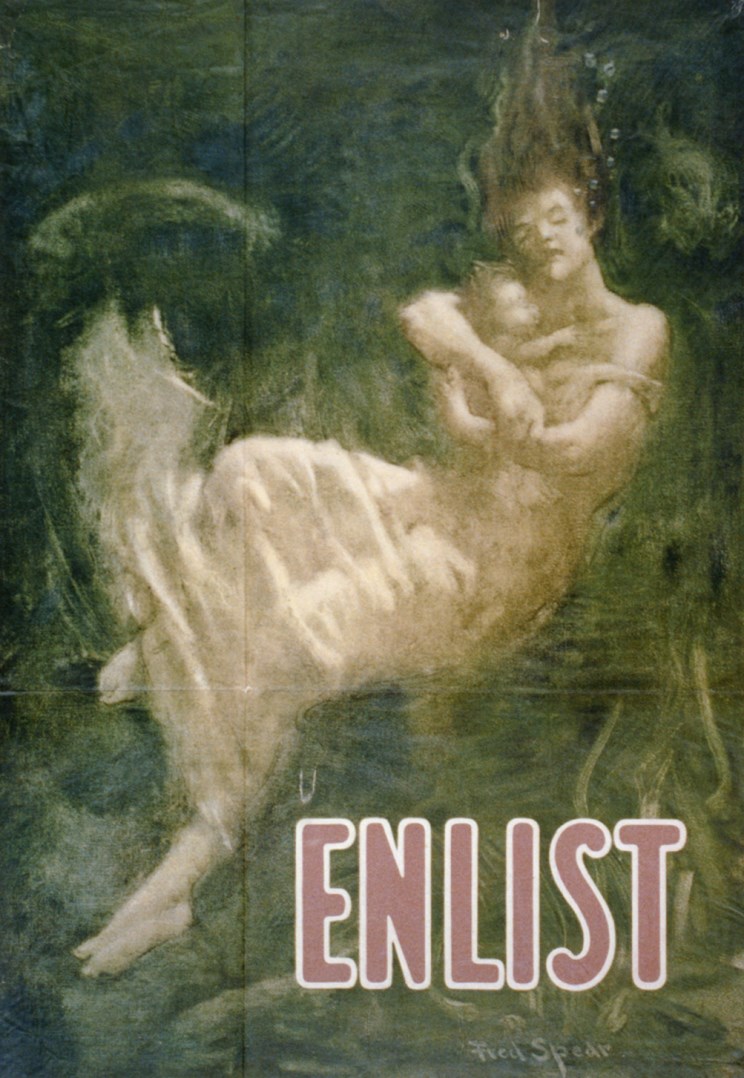

Germany adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare on February 18, 1915. The German embassy took out ads in American newspapers, warning that ships sailing into the war zone, did so at their own risk. That didn’t seem to bother anyone as they boarded RMS Lusitania.

Germany adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare on February 18, 1915. The German embassy took out ads in American newspapers, warning that ships sailing into the war zone, did so at their own risk. That didn’t seem to bother anyone as they boarded RMS Lusitania.

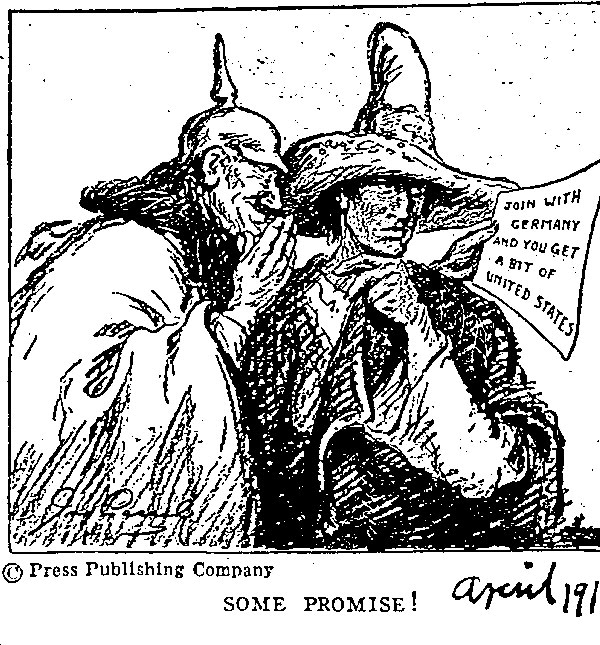

Unrestricted submarine warfare was resumed the same month. In February a German U-boat fired two torpedoes at the SS California off the Irish coast, killing 43 of her 205 passengers and crew. President Wilson asked for a declaration of war in a speech to a joint session of Congress on April 2. From the text of the speech, it seems the Germans were right. It was the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare which provoked the United States to enter the war against Germany, which it did when Congress declared war on April 6.

Unrestricted submarine warfare was resumed the same month. In February a German U-boat fired two torpedoes at the SS California off the Irish coast, killing 43 of her 205 passengers and crew. President Wilson asked for a declaration of war in a speech to a joint session of Congress on April 2. From the text of the speech, it seems the Germans were right. It was the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare which provoked the United States to enter the war against Germany, which it did when Congress declared war on April 6.

You must be logged in to post a comment.