Emil Joseph Kapaun was the son of Czech immigrants, a farm kid who grew up in 1920s Kansas. Graduating from Pilsen High, class of 1930, he spent much of the 30s in theological seminary, becoming an ordained priest of the Roman Catholic faith on June 9, 1940.

Kapaun served as military chaplain toward the end of WWII, before leaving the army in 1946 and rejoining, in 1948.

Father Kapaun was ordered to Korea a month after the North invaded the South, joining the 8th Cavalry Regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division, out of Fort Bliss.

Kapaun’s unit entered combat at the Pusan perimeter, moving steadily northward through the summer and fall of 1950. He would minister to the dead and dying performing baptisms, hearing first confessions, offering Holy Communion and celebrating Mass from an improvised altar set up on the hood of a jeep.

Father Kapaun once lost his Mass kit to enemy fire. He earned a Bronze Star in September that year, when he ran through intense enemy fire to rescue a wounded soldier. This was no rear-echelon ministry.

A single regiment was attacked by the 39th Chinese Corps on November 1, and completely overrun the following day. For the 8th Cav., the battle of Unsan was one of the most devastating defeats of the Korean War. Father Kapaun was ordered to evade, an order he defied. He was performing last rites for a dying soldier, when he was seized by Chinese communist forces.

Prisoners were force marched 87 miles to a Communist POW camp near Pyoktong, in North Korea. Conditions in the camp were gruesome. 1st Lt. Michael Dowe was among the prisoners, it’s through him that we know much of what happened there. Dowe later described Father Kapaun trading his watch for a blanket, only to cut it up to fashion socks for the feet of fellow prisoners.

Father Kapaun would risk his life, sneaking into the fields around the prison compound to look for something to eat. He would always bring it back to the communal pot.

Chinese Communist guards would taunt him during daily indoctrination sessions, “Where is your god now?” Before and after these sessions he would move through the camp, ministering to Catholic and non-Catholic alike. Kapaun would slip in behind every work detail, cleaning latrines while other prisoners argued over who’d get the job. He’d wash the filthy laundry of those made weak and incontinent with dysentery.

Starving, suffering from a blood clot in his leg and a severe eye infection, Father Kapaun led Easter services in April, 1951. A short time later, he was incapacitated. Chinese guards carried him off to a “hospital” – a fetid, stinking part of the camp known to prisoners as the “Death House”, from which few ever returned. “If I don’t come back”, he said, “tell my Bishop that I died a happy death.”

In the end, Father Kapaun was too weak to lift the plate holding the meager ration the guards had left for him. United States Army records report that Fr. Kapaun died of pneumonia on May 6, 1951.

His fellow prisoners will tell you that he died on the 23rd, of malnutrition and starvation. He was only 35.

Scores of men credit their survival to Chaplain Kapaun. In 2013, President Barack Obama presented Kapaun’s family with the Medal of Honor, posthumously, for his heroism at Unsan. The New York Times reported that April, “The chaplain “calmly walked through withering enemy fire” and hand-to-hand combat to provide medical aid, comforting words or the last rites of the Roman Catholic Church to the wounded, the citation said. When he saw a Chinese soldier about to execute a wounded comrade, Sgt. First Class Herbert A. Miller, he rushed to push the gun away. Mr. Miller, now 88, was at the White House for the ceremony with other veterans, former prisoners of war and members of the Kapaun family”.

Pope John Paul II named Father Kapaun a “Servant of God” in 1993, the first step toward Roman Catholic Sainthood. On November 9, 2015, the Catholic Diocese of Wichita submitted a 1,066 page report on the life of Chaplain Kapaun, to the Roman Curia at the Vatican. A team of six historians reviewed the case for beatification and delivered a unanimous decision on June 21, 2016, approving the petition.

In January 2022 it was announced, that the Vatican is considering a declaration of martyrdom for the Catholic faith. If granted it’s an important step on Father Emil Kapaun’s continuing road, to canonization.

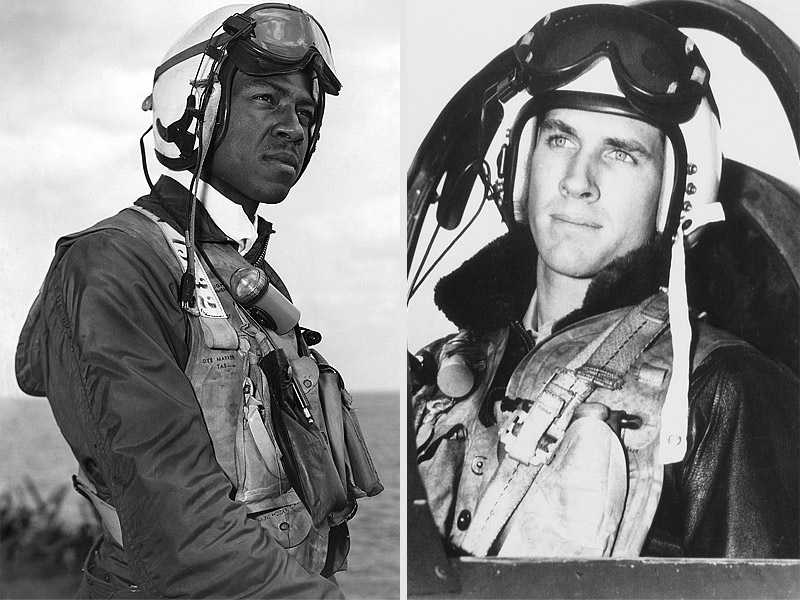

Hudner acted on instinct, deliberately crash landing his own aircraft and, now injured, running across the snow to the aid of his friend and wing man. Hudner scooped snow onto the fire with his bare hands in the bitter 15° cold, burning himself in the progress while Brown faded in and out of consciousness. Soon, a Marine Corps helicopter pilot landed, to help out. The two tore into the stricken aircraft with an axe for 45 minutes, but could not free the trapped pilot.

Hudner acted on instinct, deliberately crash landing his own aircraft and, now injured, running across the snow to the aid of his friend and wing man. Hudner scooped snow onto the fire with his bare hands in the bitter 15° cold, burning himself in the progress while Brown faded in and out of consciousness. Soon, a Marine Corps helicopter pilot landed, to help out. The two tore into the stricken aircraft with an axe for 45 minutes, but could not free the trapped pilot.

On June 25, 1950, ten divisions of the North Korean People’s Army launched a surprise invasion of their neighbor to the south. The 38,000-man army of the Republic of Korea didn’t have a chance against 89,000 men sweeping down in six columns from the north. Within hours, the shattered remnants of the army of the ROK and its government, were streaming south toward the capital of Seoul.

On June 25, 1950, ten divisions of the North Korean People’s Army launched a surprise invasion of their neighbor to the south. The 38,000-man army of the Republic of Korea didn’t have a chance against 89,000 men sweeping down in six columns from the north. Within hours, the shattered remnants of the army of the ROK and its government, were streaming south toward the capital of Seoul.

Untold thousands of Tootsie roll wrappers littered the seventy-eight miles back to the sea. Most credit their survival to the energy provided by the chocolate candy. It turns out that frozen tootsie rolls make a swell putty too, useful for patching up busted hoses and vehicles.

Untold thousands of Tootsie roll wrappers littered the seventy-eight miles back to the sea. Most credit their survival to the energy provided by the chocolate candy. It turns out that frozen tootsie rolls make a swell putty too, useful for patching up busted hoses and vehicles.

Emil Joseph Kapaun was the son of Czech immigrants, a farm kid who grew up in 1920s Kansas. Graduating from Pilsen High, class of 1930, he spent much of the 30s in theological seminary, becoming an ordained priest of the Roman Catholic faith on June 9, 1940.

Emil Joseph Kapaun was the son of Czech immigrants, a farm kid who grew up in 1920s Kansas. Graduating from Pilsen High, class of 1930, he spent much of the 30s in theological seminary, becoming an ordained priest of the Roman Catholic faith on June 9, 1940. A single regiment was attacked by the 39th Chinese Corps on November 1, and completely overrun the following day. For the 8th Cav., the battle of Unsan was one of the most devastating defeats of the Korean War. Father Kapaun was ordered to evade, an order he defied. He was performing last rites for a dying soldier, when he was seized by Chinese communist forces.

A single regiment was attacked by the 39th Chinese Corps on November 1, and completely overrun the following day. For the 8th Cav., the battle of Unsan was one of the most devastating defeats of the Korean War. Father Kapaun was ordered to evade, an order he defied. He was performing last rites for a dying soldier, when he was seized by Chinese communist forces. Chinese Communist guards would taunt him during daily indoctrination sessions, “Where is your god now?” Before and after these sessions, he would move through the camp, ministering to Catholic and non-Catholic alike. Kapaun would slip in behind every work detail, cleaning latrines while other prisoners argued over who’d get the job. He’d wash the filthy laundry of those made weak and incontinent with dysentery.

Chinese Communist guards would taunt him during daily indoctrination sessions, “Where is your god now?” Before and after these sessions, he would move through the camp, ministering to Catholic and non-Catholic alike. Kapaun would slip in behind every work detail, cleaning latrines while other prisoners argued over who’d get the job. He’d wash the filthy laundry of those made weak and incontinent with dysentery. In the end, he was too weak to lift the plate that held the meager meal the guards left for him. US Army records report that he died of pneumonia on May 6, 1951, but his fellow prisoners will tell you that he died on May 23, of malnutrition and starvation. He was 35.

In the end, he was too weak to lift the plate that held the meager meal the guards left for him. US Army records report that he died of pneumonia on May 6, 1951, but his fellow prisoners will tell you that he died on May 23, of malnutrition and starvation. He was 35.

Kapaun served as military chaplain toward the end of WWII, before leaving the army in 1946, and rejoining in 1948.

Kapaun served as military chaplain toward the end of WWII, before leaving the army in 1946, and rejoining in 1948.

Starving, suffering from a blood clot in his leg and a severe eye infection, Father Kapaun led Easter services in April, 1951. He was incapacitated a short time later. Chinese guards carried him off to a “hospital” – a fetid, stinking part of the camp known to prisoners as the “Death House”, from which few ever returned. “If I don’t come back”, he said, “tell my Bishop that I died a happy death.”

Starving, suffering from a blood clot in his leg and a severe eye infection, Father Kapaun led Easter services in April, 1951. He was incapacitated a short time later. Chinese guards carried him off to a “hospital” – a fetid, stinking part of the camp known to prisoners as the “Death House”, from which few ever returned. “If I don’t come back”, he said, “tell my Bishop that I died a happy death.” Pope John Paul II named Father Kapaun a “Servant of God” in 1993, the first step toward Roman Catholic Sainthood. On November 9, 2015, the Catholic Diocese of Wichita submitted a 1,066 page report on the life of Chaplain Kapaun, to the Roman Curia at the Vatican. A team of six historians reviewed the case for beatification. On June 21, 2016, the committee unanimously approved the petition. At the time I write this, Father Emil Joseph Kapaun’s supporters continue working to have him declared a Saint of the Roman Catholic Church, for his lifesaving ministrations at Pyoktong.

Pope John Paul II named Father Kapaun a “Servant of God” in 1993, the first step toward Roman Catholic Sainthood. On November 9, 2015, the Catholic Diocese of Wichita submitted a 1,066 page report on the life of Chaplain Kapaun, to the Roman Curia at the Vatican. A team of six historians reviewed the case for beatification. On June 21, 2016, the committee unanimously approved the petition. At the time I write this, Father Emil Joseph Kapaun’s supporters continue working to have him declared a Saint of the Roman Catholic Church, for his lifesaving ministrations at Pyoktong.

Sixteen countries sent troops to South Korea’s aid, about 90% of whom were Americans. The Soviets sent material aid to the North, while Communist China sent troops. The Korean War lasted three years, causing the death or disappearance of over 2,000,000 on all sides, combining military and civilian.

Sixteen countries sent troops to South Korea’s aid, about 90% of whom were Americans. The Soviets sent material aid to the North, while Communist China sent troops. The Korean War lasted three years, causing the death or disappearance of over 2,000,000 on all sides, combining military and civilian. The night-time satellite image of the two Koreas, tells the story of what happened next. In the south, the Republic of Korea (ROK) developed into a successful constitutional Republic, a G-20 nation with an economy ranking 11th in the world in nominal GDP, and 13th in terms of purchasing power parity.

The night-time satellite image of the two Koreas, tells the story of what happened next. In the south, the Republic of Korea (ROK) developed into a successful constitutional Republic, a G-20 nation with an economy ranking 11th in the world in nominal GDP, and 13th in terms of purchasing power parity. Son of the founder of the Juche Ideal, Kim Jung Il, was an enthusiastic film buff. In a move that would make Caligula blush, Kim had South Korean film maker Shin Sang Ok kidnapped along with his actress ex-wife, Choi Eun Hee. After four years spent starving in a North Korean gulag, the couple accepted Kim’s “suggestion” to re-marry and go to work for him, producing the less-than-box-office-smash “Pulgasari”, a kind of North Korean Godzilla film.

Son of the founder of the Juche Ideal, Kim Jung Il, was an enthusiastic film buff. In a move that would make Caligula blush, Kim had South Korean film maker Shin Sang Ok kidnapped along with his actress ex-wife, Choi Eun Hee. After four years spent starving in a North Korean gulag, the couple accepted Kim’s “suggestion” to re-marry and go to work for him, producing the less-than-box-office-smash “Pulgasari”, a kind of North Korean Godzilla film.

You must be logged in to post a comment.