For a variety of reasons, the eastern front of the “War to end all Wars” was a war of movement. Not so in the West. As early as October 1914, combatants burrowed into the ground like animals sheltering from what Private Ernst Jünger would come to call, the ‘Storm of Steel’.

Conditions in the trenches and dugouts must have defied description. You would have smelled the trenches long before you could see them. The collective funk of a million men and more, enduring the troglodyte existence of men who live in holes. Little but verminous scars in the earth teaming with rats and lice and swarming with flies. Time and again the shells churned up and pulverized the soil, the water and the shattered remnants of once-great forests, along with the bodies of the slain.

By the time the United States entered the ‘War to end all Wars’ in April, 1917, millions had endured three years of this existence. The first 14,000 Americans arrived ‘over there’ in June, the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) forming on July 5. American troops fought the military forces of Imperial Germany alongside their British and French allies, others joining Italian forces in the struggle against the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

You couldn’t call the stuff these people lived in mud – it was more like a thick slime, a clinging, sucking ooze capable of swallowing grown men, even horses and mules, alive.

Captain Alexander Stewart wrote “Most of the night was spent digging men out of the mud. The only way was to put duck boards on each side of him and work at one leg: poking and pulling until the suction was relieved. Then a strong pull by three or four men would get one leg out, and work would begin on the other…He who had a corpse to stand or sit on, was lucky”.

Sir Launcelot Kiggell broke down in tears, on first seeing the horror of Paschendaele, . “Good God”, he said. “Did we really send men to fight in That?”

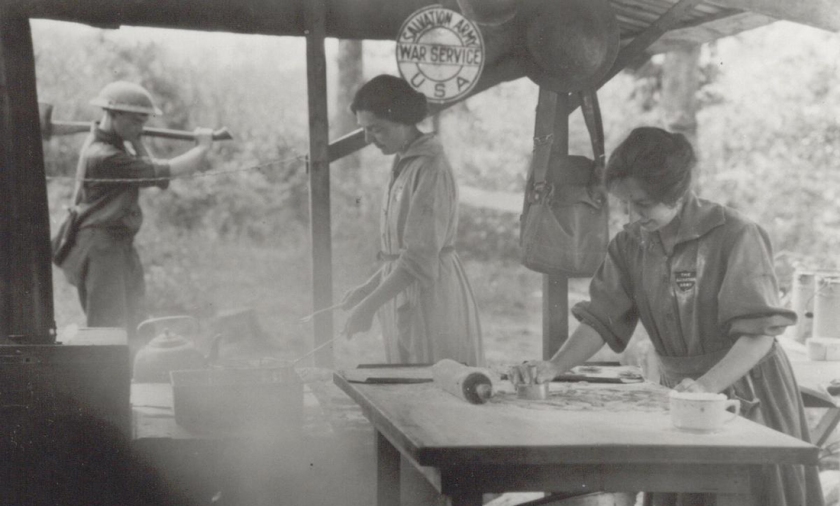

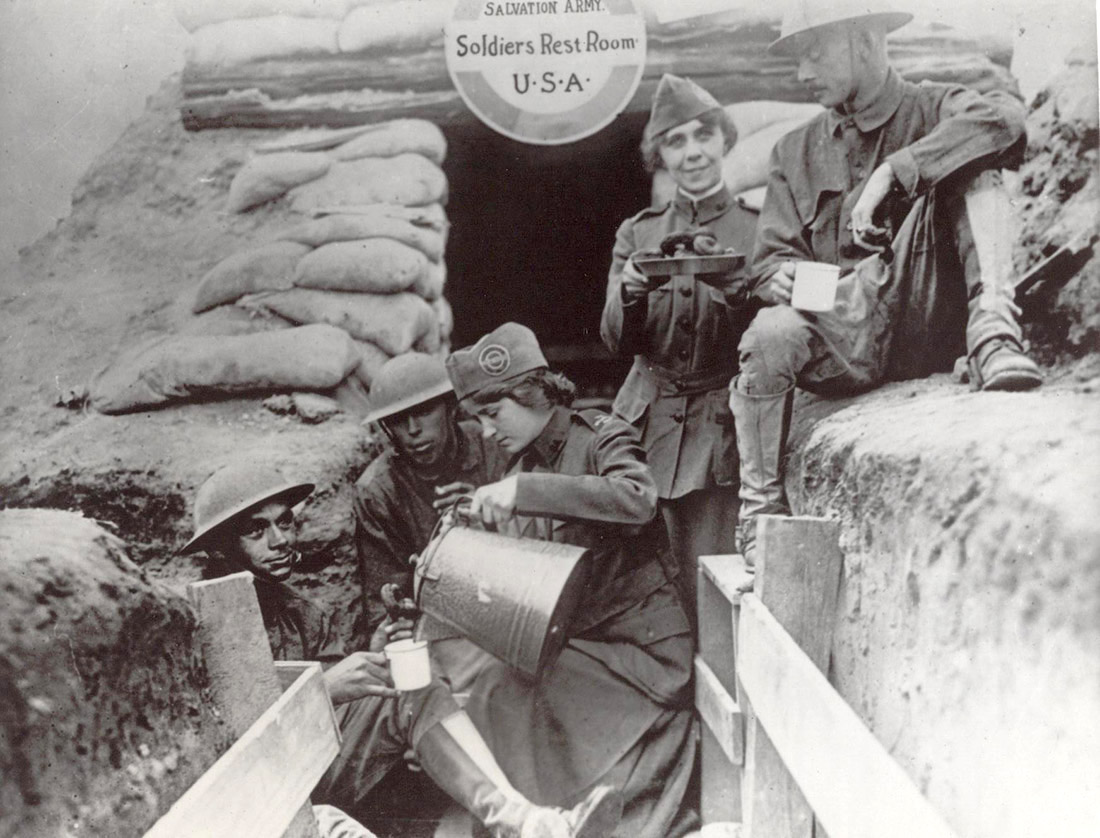

Unseen and unnoticed in times of such dread calamity, are the humanitarian workers. Those who tend to the physical and spiritual requirements and the countless small comforts, of those so afflicted.

Within days of the American declaration of war, Evangeline Booth, National Commander of the Salvation Army, responded, saying “The Salvationist stands ready, trained in all necessary qualifications in every phase of humanitarian work, and the last man will stand by the President for execution of his orders”.

These people are so much more than that donation truck, and the bell ringers we see behind the red kettles, every December.

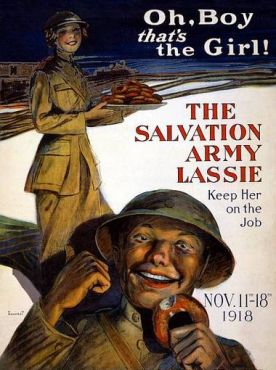

Lieutenant Colonel William S. Barker of the Salvation Army left New York with Adjutant Bertram Rodda on June 30, 1917, to survey the situation. It wasn’t long before his not-so surprising request came back in a cable from France. Send ‘Lassies’.

A small group of carefully selected female officers was sent to France on August 22. That first party comprised six men, three women and a married couple. Within fifteen months their number had expanded by a factor of 400.

In December 1917, a plea for a million dollars went out to support the humanitarian work of the Salvation Army, the YMCA, YWCA, War Camp Community Service, National Catholic War Council, Jewish Welfare Board, the American Library Association and others. This “United War Work Campaign” raised $170 million in private donations, equivalent to $27.6 billion, today.

‘Hutments’ were formed all over the front, many right out at the front lines. There were canteen services. Religious observances of all denominations were held in these facilities. Concert performances were given, clothing mended and words of kindness offered in response to all manner of personal problems. On one occasion, the Loyal Order of Moose conducted a member initiation. Pies and cakes were baked in crude ovens and lemonade served to hot and thirsty troops.

Of all these corporal works of mercy, the ones best remembered by the ‘doughboys’ themselves, were the doughnuts.

Helen Purviance, sent to France in 1917 with the American 1st Division, seems to have been first with the idea. An ensign with the Salvation Army, Purviance and fellow ensign Margaret Sheldon first formed the dough by hand, later using a wine bottle in lieu of a rolling pin. Having no doughnut cutter at the time, dough was shaped and twisted into crullers, fried seven at a time in a lard-filled helmet, on a pot-bellied wood stove.

The work was grueling. The women worked well into the night that first day, serving all of 150 hand-made doughnuts. “I was literally on my knees,” Purviance recalled, but it was easier than bending down all day, on that tiny wood stove. It didn’t seem to matter. Men stood in line for hours, patiently waiting in the mud and the rain of that world of misery, for their own little piece of warm, home-cooked heaven.

Techniques gradually improved and it certainly helped, when these there was a real pan to cook in. These ladies were soon turning out 2,500 to 9,000 doughnuts a day. An elderly French blacksmith made Purviance a doughnut cutter, out of a condensed milk can and a camphor-ice tube, attached to a wooden block.

Before long the pleasant aroma of hot doughnuts could be detected, wafting all over the dugouts and trenches of the western front. Salvation Army volunteers and others made apple pies and all manner of other goodies, but the name that stuck, was “Doughnut Lassies”.

One New York Times correspondent wrote in 1918 “When I landed in France I didn’t think so much of the Salvation Army; after two weeks with the Americans at the front I take my hat off… [W]hen the memoirs of this war come to be written the doughnuts and apple pies of the Salvation Army are going to take their place in history”.

Contrary to popular myth the doughnut was not invented in WW1. Neither was the name for soldiers of the Great War although millions of “doughboys” returned from ‘over there’ requesting wives, mothers sweethearts and local bakeries make their newfound favorite confection. Russian émigré Adolph Levitt invented the first doughnut machine in 1920. The round cake with the hole in the middle, has never looked back.

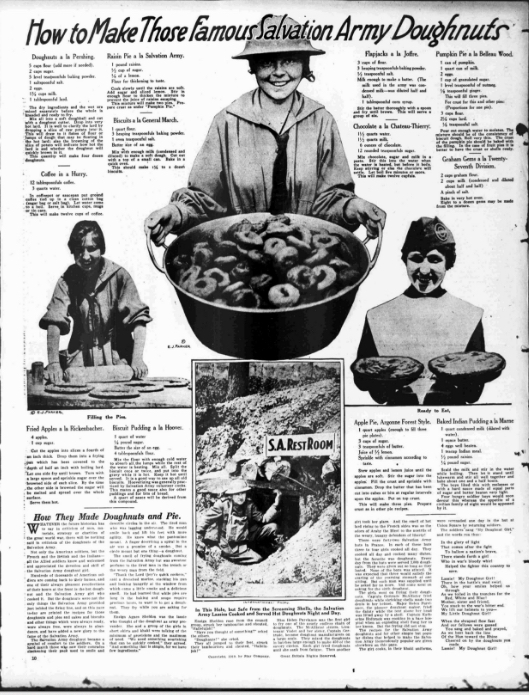

If you’re interested, the Doughnut Lassies’ original WW1 recipe may be found, HERE. Let me know how they come out.

100 years later, two fingers and a tooth were purchased at auction, and since rejoined their fellow digit at the Museo Galileo. To this day these are the only human body parts, in a museum otherwise devoted to scientific instrumentation.

100 years later, two fingers and a tooth were purchased at auction, and since rejoined their fellow digit at the Museo Galileo. To this day these are the only human body parts, in a museum otherwise devoted to scientific instrumentation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.