Over seventy years in compilation, only a single individual is credited with more entries in the greatest reference work in the history of the English language than this one murderer, working from a cell in a mental institution.

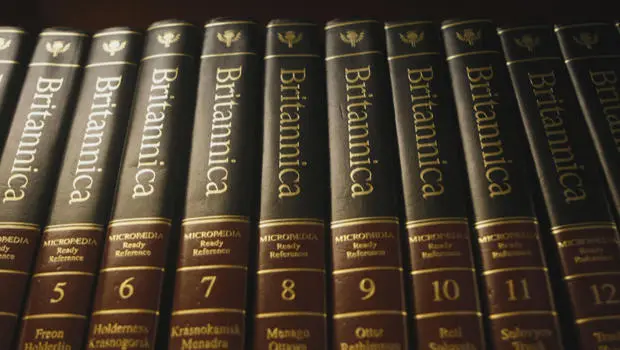

For the great reference works of the English language, the beginnings were often surprisingly modest. The outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishment known as the Scottish Enlightenment produced among other works the Encyclopedia Britannica, first published on December 6, 1768 in Edinburgh, Scotland.

Webster’s dictionary began with a single infantrymen of the American Revolution, who went on to codify what would become the standardized system of spelling for “American English“. In Noah Webster’s dictionary, ‘colour’ became ‘color’, and programme’ became ‘program’. It was a novel concept at a time when the very thought of a “correct“ way of spelling, was new and unfamiliar.

Among the entire catalog of works there is no tale so strange as the Oxford English dictionary, and the convicted murderer who helped bring it to life.

No, really. From an insane asylum, no less.

Dissatisfied with what were at that time a spare four reference works including Webster’s dictionary, the Philological society of London first discussed what was to become the standard reference work of the English language, in 1857.

The work was expected to take 10 years in compilation and cover some 64,000 pages. The editors were off, by about sixty years. Five years into the project the team had made it all the way up, to “ant“.

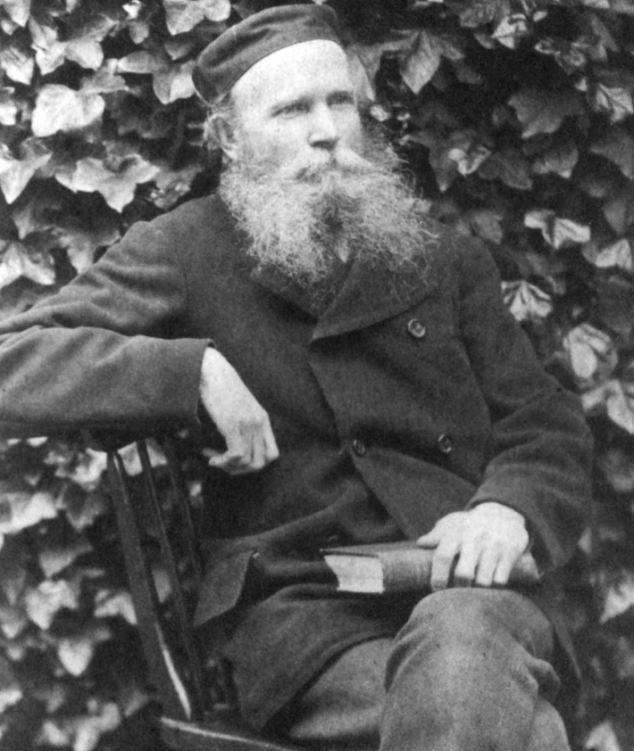

William Chester Minor was a physician around this time, serving with the Union army during the American Civil War.

The role of this experience in the man’s later psychosis, is impossible to know. Minor was in all likelihood a paranoid schizophrenic, a condition poorly understood in his day.

As a combat surgeon, Minor saw things no man was ever meant to see. Terrible mutilation was inflicted on both sides at the 1864 Battle of the Wilderness. Hundreds were wounded and unable to get out of the way of the brush fire, burning alive before the horrified eyes of comrade and foe alike, the poor unfortunate sufferers too broken to move. One soldier would later write: It was as though “hell itself had usurped the place of earth“.

At one point, Dr. Minor was ordered to brand the forehead of an Irish deserter with the letter “D”. The episode scarred the soldier, and left the doctor with paranoid delusions. The Irish were coming to ‘get him’. He Knew they were.

In his paranoid delusions, the faceless form of man would slither out of the attic at night and watch Minor as he slept, in his hands a tray of metal biscuits, slathered in poison. The Fenian Brotherhood was out to Get him. He could almost hear their dark whispered conversations, on gaslit streets.

As a child born to New England missionaries working in Ceylon, (now Sri Lanka), Minor was comfortable with the idea of foreign travel as a means of dealing with difficulty. He took a military pension and moved to London in 1871, to escape the demons who were by that time, closing in.

Minor’s tormentors followed. He would lie in his bed at night frozen with fear and each night, his tormenter would return. Regular visits to Scotland Yard would result in little more than polite thanks, and a few useless notes scribbled on paper. Dr. Minor would have to deal with this himself. He took to sleeping with a loaded Colt .38, beneath his pillow.

On February 17, 1862, Minor woke to find the shadow of a man, standing over him. The apparition dove for the window and Minor followed him, into the street.

It was 2:00 in the morning and hardly anyone was out, save for one man. George Merrett was a father of 6 with a pregnant wife, who worked at the Red Lion Brewery, as a coal stoker. He was walking to work.

Minor’s nighttime apparitions were nothing but the paranoid delusions, of a broken mind. The three or four bullets he fired at a man walking to work, were very real. George Merrett was dead before the police got there.

Minor was tried and found not guilty by reason of insanity, and remanded “until Her Majesty’s Pleasure be known” to the Broadmoor institution for the criminally insane. Victorian England was by no means ‘enlightened’ by modern standards, and inmates were always referred to as ‘criminals’ and ‘lunatics’. Never as ‘patients’. Yet Broadmoor, located on 290 acres in the village of Crowthorne in Berkshire was England’s newest such asylum, and a long way from previous such institutions.

Minor was housed in block 2, the “Swell Block”, where his military pension and family wealth afforded him two rooms instead of the usual one.

Minor would acquire books, so many over time that one room was converted to a library.

Surprisingly, it was Merritt’s widow Eliza, who delivered many of his books. The pair became friends and Minor used a portion of his wealth to “pay” for his crime, and to help the widow raise her six kids.

Dr. James Murray assumed editorship of the “Big Dictionary” of English in 1879, and issued an appeal in magazines and newspapers, for outside contributions. Whether this seemed a shot at redemption to William Minor or merely something to do with his time is anyone’s guess, but Minor had nothing but time. And books.

William Minor collected his first quotation in 1880 and continued to do so for twenty years, always signing his submissions: Broadmoor, Crowthorne, Berkshire.

The scope of the man’s work was prodigious, he himself an enigma, assumed to be some country gentlemen. Perhaps one of the overseers, at the asylum.

In 1897, “The Surgeon of Crowthorne” failed to attend the Great Dictionary dinner. Dr. Murray decided to meet his mysterious contributor in person and finally did so, in 1901. In his cell.

Oh, to have been a fly on the wall when this Oxford don was ushered into the office of Broadmoor’s director, only to learn the man he was searching for, was an inmate.

Dr. Minor would carefully index and document each entry, which editors compared with the earliest such word use submitted by other lexicographers. In this manner over 10,000 of his submissions made it into the finished work including the words ‘colander’, ‘countenance’ and ‘ulcerated’.

By 1902, Minor’s paranoid delusions had crowded out what remained, of his mind. He believed he was being kidnapped and spirited away to Istanbul where he was sexually abused and forced to commit such abuse, himself. His submissions came to an end. Home Secretary Winston Churchill ordered Minor deported back to the United States, following a 1910 episode in which the man emasculated himself, with a knife.

The madman lived out the last ten years of his life in various institutions for the criminally insane. William Chester Minor died in 1920 and went to his rest in a small and inauspicious grave, in Connecticut.

Over seventy years in compilation, only a single individual is credited with more entries in the greatest reference work in the history of the English language than this one murderer, working from a cell in a mental institution.

Bryan complained that evolution taught children that humans were no more than one among 35,000 mammals. He rejected the idea that humans were descended from apes. “Not even from American monkeys, but from old world monkeys”. The ACLU wanted to oppose the Butler Act on grounds that it violated the teacher’s individual rights and academic freedom, but it was Darrow who shaped the case, taking the position that theistic and evolutionary views were not mutually exclusive.

Bryan complained that evolution taught children that humans were no more than one among 35,000 mammals. He rejected the idea that humans were descended from apes. “Not even from American monkeys, but from old world monkeys”. The ACLU wanted to oppose the Butler Act on grounds that it violated the teacher’s individual rights and academic freedom, but it was Darrow who shaped the case, taking the position that theistic and evolutionary views were not mutually exclusive.

You must be logged in to post a comment.