Acts of heroism have a way of popping up in the most unexpected places. Ordinary people rising to the occasion, in the most extraordinary of circumstances.

Temar Boggs and Chris Garcia were two teenage boys who chased down a kidnapper – on their bicycles no less – to free a little girl. Eight-months pregnant mother-to-be Lauren Prezioso dove into an Australian undertow to save two boys, being swept out to sea. Six-year-old Bridger Walker threw himself in the path of a vicious dog to take the mauling directed at his little sister, only seconds earlier.

This is one of those stories.

Jonathon Luther Jones lived near Cayce Kentucky as a boy, and the nickname stuck. For reasons which remain unclear he preferred to spell it, “Casey”.

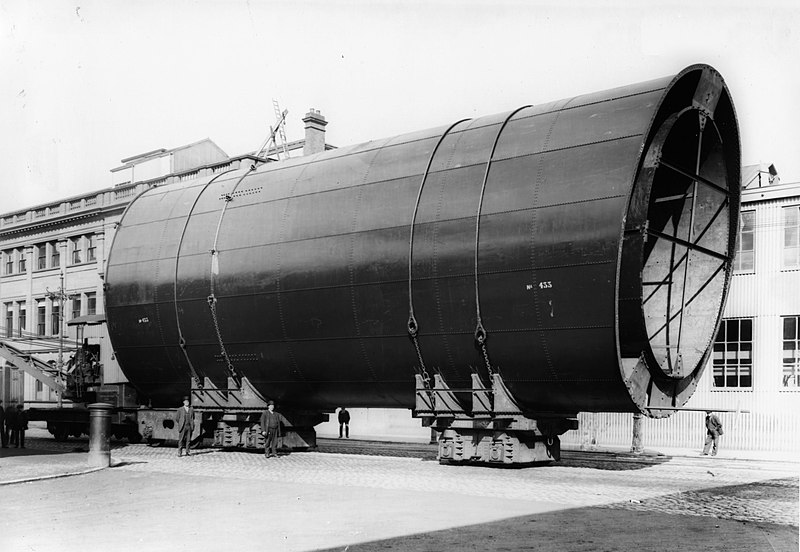

Casey Jones was a train man, working on the I.C.R.R. The Illinois Central Railroad.

An example of the man’s character comes to us from 1895, when Jones was thirty-two. Outside Michigan City Mississippi, a group of children darted across the tracks, fewer than sixty yards from a speeding train. Most made it across except one little girl, who froze in terror before the oncoming locomotive.

With fellow engineer Bob Stevenson hauling back on the emergency brakes and buying precious extra seconds, Jones ran across the running boards and inched his way down the pilot, better known as the “cow catcher”.

He was no trick rider. No circus acrobat. Casey Jones worked on the railroad and yet, bracing himself with his legs, Jones reached out and scooped up the terrified little girl, at the last possible fraction of a second.

On this occasion, the man had every hope and expectation of remaining alive. Five years later Casey Jones’ last act of heroism came in the face of certain, and violent death.

Casey Jones went to work for the Mobile & Ohio Railroad where he performed well, receiving first a promotion to brakeman, and then to fireman. He met Mary Joanna (“Janie”) Brady around this time, whose father owned the boarding house, where Jones lived. The pair fell in love and married on November 11, 1886, buying a house in Jackson Alabama where the couple raised their three children. By all accounts the man was sober and devoted to his work, a dedicated family man.

Several crews from the Illinois Central Railroad (IC) were down with yellow fever in the summer of 1887. Fireman Jones went to work for the IC the following year, firing a freight run between Jackson, Tennessee, and Water Valley, Mississippi.

Casey Jones had a knack for these complex and powerful machines. He was good at what he did and an aggressive risk taker. Ambitious for advancement, Jones was issued nine citations for rules infractions over the course of his career, resulting in 145 days’ suspension. He was well liked by fellow railroaders but widely regarded, as just this side of reckless.

Jones achieved his lifelong goal of becoming an engineer in 1891. He was well known, for being on time. Jones insisted he’d never “fall down” and get behind schedule. People learned to set their watches by his train whistle, knowing he would always “get her there on the advertised” (time).

Jones moved his family to Memphis in 1900, transferring to the “cannonball run” between Chicago and New Orleans. The run was a four train passenger relay, advertising the fastest travel times in the history of the American railroad. Experienced engineers were worried about the ambitious schedule and some even quit. Jones saw the new itinerary as an opportunity for advancement.

On this day in 1900, Engine #382 departed Memphis at 12:05am, ninety-five minutes behind schedule due to the late arrival of the first leg, of the relay. The Memphis to Canton, Mississippi run was 190 miles long and normally took 4 hours, 50 minutes at an average speed of 39 MPH. 95 minutes was a lot of time to make up but #382 was a fast engine and traveling “light” that night, with only six cars.

Fireman Simeon Taylor “Sim” Webb was one of the best. He would have to be. This would be a record breaking run.

Jones hit the Johnson bar, throttling #382 up to 80 MPH despite sharp turns and visibility reduced, by fog. There were two stops for water and a brief halt on a side track, to let another engine through. Despite all that, #382 made up most of those 95 minutes by the 155-mile mark. On leaving the side track in Goodman, Mississippi, Jones was only five minutes behind the advertised arrival, of 4:05am.

Jones was well acquainted with those last 25 miles into Vaughn Mississippi. There were few turns and the engineer throttled his engine up to breakneck speed. He was thrilled with his time, saying “Sim, the old girl’s got her dancing slippers on tonight!”

Unknown to both men there was a problem, up ahead. Three trains were in the station at Vaughn with a combined length of ten cars longer, than the main siding. Rail yard workers performed a “saw by” maneuver, backing #83 onto the main line and switching overlapping cars onto the “house track”. Then there was that problem with an air hose. Four cars remained stranded on the main line.

#382 sped through the final curve at 75MPH, only two minutes behind schedule. Clinging to the side board, Sim Webb was the first to see the red lights, of the caboose. “Oh my Lord”, he yelled, “there’s something on the main line!”

Jones didn’t have a prayer of stopping in time. He was moving too fast. He reversed throttle and slammed the air brakes into emergency stop, screaming “Jump Sim, jump!” Sim Webb jumped clear with only 300 feet to go as the piercing shriek of the engine’s whistle, split the air.

Jones could have jumped. Having ordered Webb to do so demonstrated, the man understood the situation. Casey Jones stayed on the train as “Ole 382” plowed through the red wooden caboose and three freight cars, before leaving the track.

By the moment of impact, Jones frantic efforts had slowed the engine down to 35 miles per hour. Untold numbers of passengers were saved from serious injury, or death. As the pieces came to a stop Jones himself, was the only fatality. His watch was stopped at 3:52am, only two minutes behind schedule.

Adam Hauser of the New Orleans Times-Democrat was a passenger in a sleeper car, at the time of the wreck: “The passengers did not suffer” he said, “and there was no panic. I was jarred a little in my bunk, but when fairly awake the train was stopped and everything was still. Engineer Jones did a wonderful as well as a heroic piece of work, at the cost of his life”.

Legend has it that, when Jones’ body was removed his dead hands still clutched the whistle cord, and the brake.

Since that day Casey Jones has achieved mythological status, alongside the likes of Pecos Bill and Paul Bunyan. “The Ballad of Casey Jones” was recorded by Mississippi John Hurt, Johnny Cash and the Grateful Dead, among others.

Jones’ son Charles was 12 at the time of his father’s death at age 37. Jones’ daughter Helen, was 10. The youngest, John Lloyd (“Casey Junior”) was 4. Janie received two life insurance payments totaling $3,000 as Casey was “Double Heading” at that time, as a member of two unions. Casey Jones widow would receive no other compensation. The Railroad Retirement Fund wouldn’t come about, for another 37 years.

Mary Joanna “Janie” Brady Jones lived another 58 years and never had so much as a thought, of remarrying. The idea that the hero she married was intoxicated at the time of the accident was a thorn in her side, for the rest of her life. What’s more there were allegations that she herself, was an unfaithful wife. According to one version of the song she told her heartbroken children to stop crying. They had “another papa on the Salt Lake Line.”

One particularly snotty article in Time Magazine informed the reader the “Widow Jones” … “looks well and buxom,” in a piece that couldn’t so much as get Jones’ engine number right. To their credit, Time Magazine itself criticized their tone, in 2015. 57 years after Janie died, at the age of 92.

Janie Jones lived another 58 years. She wore black every day, for the rest of her life.

A Trivial Matter

In 1907, brakeman Jesus Garcia stuck to the controls to drive a flaming train away from the small mining town of Nacozari, in the Mexican state of Sonora. The train was carrying dynamite, and blew up, Killing Garcia. His quick actions had saved the town where Jesus Garcia is remembered as a hero, to this day.

Fifteen years before Angus “Mac” MacGyver hit your television screen, mission control teams, spacecraft manufacturers and the crew itself worked around the clock to “MacGyver” life support, navigational and propulsion systems. For four days and nights, the three-man crew lived aboard the cramped, freezing Aquarius, a landing module intended to support a crew of 2 for only a day and one-half.

Fifteen years before Angus “Mac” MacGyver hit your television screen, mission control teams, spacecraft manufacturers and the crew itself worked around the clock to “MacGyver” life support, navigational and propulsion systems. For four days and nights, the three-man crew lived aboard the cramped, freezing Aquarius, a landing module intended to support a crew of 2 for only a day and one-half.

You must be logged in to post a comment.