It’s hard to turn on the TV this week, without hearing about Apollo 11. Fifty years ago, those famous words spoken by the first human being, to set foot on the moon. “That’s one small step for (a) man, one giant leap for mankind“.

The moon landing of July 20, 1969 was the culmination of tens of millions of man-hours, a twelve-years long space race with the Soviet Union, five dead astronauts and the young President who had dared them to do it, himself shot through the head some six years earlier.

On this day in 1969, two grown men descended to the face of the lunar body in a vehicle so shockingly delicate, as to be incapable of supporting its own weight outside the zero gravity of space. It was the technological triumph of the 20th century. A feat accomplished with less computing horsepower, than an old iPhone.

Ten years earlier, NASA needed to know what happened to the human body in space. The Soviet space program was halted for nearly a year, so sick was the #2 (human) “traveler in the cosmos”. Astronauts would be subjected to weightlessness, G-forces beyond imagination and constant rotation. A world where up is down and down is up and the delicate sensors of the middle ear cry out, Enough!

The vertigo and the nausea of motion sickness has played its part, from the earliest days of human history. The ancient Greek physician Hippocrates wrote about it. The Roman philosopher Seneca writes of the misery of a long voyage in which ‘he could bring nothing more up’. The lyric poet Horace writes of seasickness as a great social leveler, in which wealth is no protection and the rich man suffers just as much as the poor man. The sea-going military exploits of Julius Caesar are replete with tales of vomiting legionaries and seasick horses.

To the Great good fortune of the Protestant England of 1588, the terrifying Armada sent by Spanish King Phillip II to overthrow Queen Elizabeth I was commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an Army general with little to no experience at sea. Sidonia suffered such severe seasickness that this, combined with a stroke of exceptionally bad luck, destroyed the Spanish Armada and paved the way to the next three hundred years in which “Britannia Ruled the Waves”.

Were you to catch the early space travelers in a candid moment, many are the tales of less-than-heroic moments, spent wiping the product of space sickness from the interiors of craft from the Gemini program to the Space Shuttle.

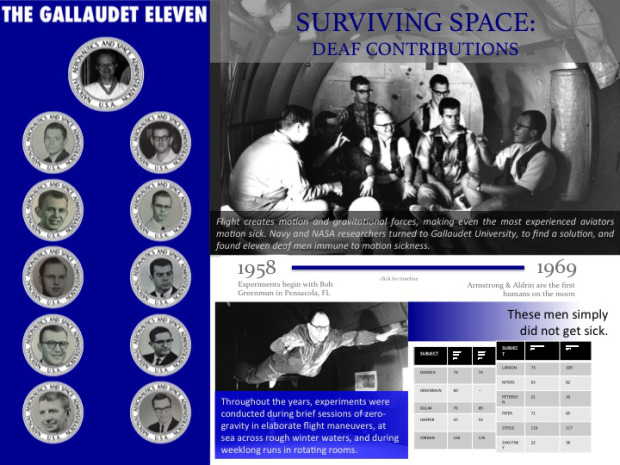

From the beginning, scientists needed to understand the mechanisms of space sickness. So it was that, in the mid-twentieth century, NASA happened upon a group of space pioneers, you’ve likely never heard of. What better group with which to study motion sickness, than those literally immune to it. The profoundly hearing impaired made deaf by spinal meningitis and without a functioning vestibular system, that delicate inner ear structure which gives us sense of balance.

Gallaudet University was founded in 1864 as a grammar school for the deaf and blind and remains to this day, the world’s premier institution for the higher education of the deaf and hearing impaired. In 1961, researchers with the US Naval School of Aviation Medicine paid a visit. Hundreds of faculty and students were tested and a handful selected, for further tests. There were parabolic flights. Some were suspended for days, in swinging cages.

One group was deliberately taken into a severe storm off the coast of Nova Scotia, an outing former students remember as a lark, a thoroughly enjoyable adventure. Researchers didn’t enjoy the trip quite so much, passing the voyage in a state of green and gut-wrenching decrepitude.

Gallaudet Eleven

Eleven Gallaudet students were selected as early as 1958, to spin for nearly two weeks in a room-sized centrifuge. Though it was hard work, participants viewed the study as an adventure. One remembers his experience as a way to serve his country, since he’d never be allowed to join the military.

Today, their names are all but forgotten. Barron Gulak. Harry Larson. David Myers and others. The forgotten pioneers of those early days of the American space program, without whom the first astronauts may well have viewed the moon landing, from the bottom of a barf bag.

Featured image, top of page: “Space Sickness”. Hat tip graphic designer Douglas Noe (aka “Robotrake”), and society6.com

Erie Engine #237 arrived at Lackawaxen at 2:30 pm pulling 50 coal cars, loaded for Jersey City. Kent gave the all clear at 2:45. The main switch was opened, and Erie #237 joined the single track heading east out of Shohola.

Erie Engine #237 arrived at Lackawaxen at 2:30 pm pulling 50 coal cars, loaded for Jersey City. Kent gave the all clear at 2:45. The main switch was opened, and Erie #237 joined the single track heading east out of Shohola. “[T]he wooden coaches telescoped into one another, some splitting open and strewing their human contents onto the berm, where flying glass, splintered wood, and jagged metal killed or injured them as they rolled. Other occupants were hurled through windows or pitched to the track as the car floors buckled and opened. The two ruptured engine tenders towered over the wreckage, their massive floor timbers snapped like matchsticks. Driving rods were bent like wire. Wheels and axles lay broken. The troop train’s forward boxcar had been compacted and within the remaining mass were the remains of 37 men”. Witnesses saw “headless trunks, mangled between the telescoped cars” and “bodies impaled on iron rods and splintered beams.”

“[T]he wooden coaches telescoped into one another, some splitting open and strewing their human contents onto the berm, where flying glass, splintered wood, and jagged metal killed or injured them as they rolled. Other occupants were hurled through windows or pitched to the track as the car floors buckled and opened. The two ruptured engine tenders towered over the wreckage, their massive floor timbers snapped like matchsticks. Driving rods were bent like wire. Wheels and axles lay broken. The troop train’s forward boxcar had been compacted and within the remaining mass were the remains of 37 men”. Witnesses saw “headless trunks, mangled between the telescoped cars” and “bodies impaled on iron rods and splintered beams.”

As the years went by, signs of all those graves were erased. Hundreds of trains carried thousands of passengers up and down the Erie Railroad, ignorant of the burial ground through which they passed.

As the years went by, signs of all those graves were erased. Hundreds of trains carried thousands of passengers up and down the Erie Railroad, ignorant of the burial ground through which they passed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.