The name of Vermont conjures many things, the forested landscapes, ski slopes, maple syrup and mountain trout brooks. The first state to be admitted into the union formed by the 13 former colonies, the 14th state existed for as many years as an independent Republic, a distinction shared with only three other states: Texas, Hawaii and California.

Fun Fact: For a time, western districts of Florida also formed their own sovereign state: the Republic of West Florida. If you ever want to get a Texan going, ask them about the Original “Lone Star Republic“.

In the late 18th century, lands granted by the governor of New Hampshire led the colony into conflict with the neighboring province of New York. Conflict escalated over jurisdiction and appeals were made to the King, as the New York Supreme Court invalidated the “New Hampshire grants”.

Infuriated residents of the future Vermont Republic including Ethan Allen and his “Green Mountain Boys”, rose up in anger. On March 13, 1775, two Westminster Vermont natives were killed by British Colonial officials. Today we remember the event as the “Westminster Massacre”.

The battles at Lexington and Concord broke out a month later, ushering in a Revolution and eclipsing events to the north. New York consented to admitting the “Republic of Vermont” into the union in 1790, ceding all claims on the New Hampshire land grants in exchange for a payment of $30,000. Vermont was admitted as the 14th state on March 4, 1791, the first state so admitted following adoption of the federal Constitution.

Organized in 1785, the city of St. Albans forms the county seat of Franklin County, Vermont. 15 miles from the northern border and located on the eastern shore of Lake Champlain, it’s not the kind of place you’d expect for a Civil War story.

The Confederate States of America maintained government operations north of the border, from the earliest days of the Civil War. Toronto was a logical relay point for communications with Great Britain, from which the Confederate government unsuccessfully sought to gain support.

Secondly, the future Canadian nation provided a safe haven for prisoners of war, escaped from Union camps.

Former member of Congress and prominent Ohio “Peace Democrat” Clement Vallandigham fled the United States to Canada in 1863, proposing to detach the states of Illinois, Indiana and Ohio from the Union in exchange for sufficient numbers of Confederate troops, to enforce the separation. Vallandigham’s five-state “Northwestern Confederacy” would include Kentucky and Missouri, breaking the Union into three pieces. Surely that would compel Washington to sue for peace.

In April 1864, President Jefferson Davis dispatched former Secretary of the Interior Jacob Thompson, ex-Alabama Senator Clement Clay, and veteran Confederate spy Captain Thomas Henry Hines to Toronto, with the mission of raising hell in the North.

This was no small undertaking. A sizeable minority of Peace Democrats calling themselves “Copperheads” were already in vehement opposition to the war. So much so that General Ambrose Burnside declared in his General Order No. 38, that “The habit of declaring sympathy for the enemy will not be allowed in this” (Ohio) “department. Persons committing such offenses will be at once arrested with a view of being tried. . .or sent beyond our lines into the lines of their friends. It must be understood that treason, expressed or implied, will not be tolerated in this department“.

Hines and fellow Confederates worked closely with Copperhead organizations such as the Knights of the Golden Circle, the Order of the American Knights, and the Sons of Liberty, to foment uprisings in the upper Midwest.

In the late Spring and early Summer of 1864, residents of Maine may have noted an influx of “artists”, sketching the coastline. No fewer than fifty in number, these nature lovers were in fact Confederate topographers, sent to map the Maine coastline.

The Confederate invasion of Maine never materialized, thanks in large measure to counter-espionage efforts by Union agents.

J.Q. Howard, the U.S. Consul in St. John, New Brunswick, informed Governor Samuel Cony in July, of a Confederate party preparing to land on the Maine coast.

The invasion failed to materialize, but three men declaring themselves to be Confederates were captured on Main Street in Calais, preparing to rob a bank.

Disenchanted Rebel Francis Jones confessed to taking part in the Maine plot, revealing information leading to the capture of several Confederate weapons caches in the North, along with operatives in Maine, Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee and Ohio.

Captain Hines planned an early June uprising in the Northwest, timed to coincide with a raid planned by General John Hunt Morgan. Another uprising was planned for August 29, timed with the 1864 Democratic Convention in Chicago. The conspirators’ actions never lived up to the heat of their rhetoric, and both operations fizzled. A lot of these guys were more talk than action, yet Captain Hines continued to send enthusiastic predictions of success, back to his handlers in Richmond.

“Canada” itself was a loose confederation of independent provinces in 1864. At the September 1, Charlottetown Conference, politicians from the United Province of Canada and Britain’s Maritime colonies discussed a possible union.

The Toronto operation tried political methods as well, supporting Democrat James Robinson’s campaign for governor of Illinois. If elected they believed, Robinson would turn over the state’s militia and arsenal to the Sons of Liberty. They would never know. Robinson lost the election.

All this fomenting cost money, and lots of it. In October 1864, the Toronto operation came south to St. Albans, to make a withdrawal.

Today, St. Albans is a quiet town of 6,869. In 1864 the town was quite wealthy, home to manufacturing and repair facilities for railroad locomotives. Located on a busy rail line, St. Albans was also home to four banks.

Nicholasville, Kentucky native Bennett Henderson Young was a member of the Confederate 8th Kentucky Cavalry, captured during Morgan’s 1863 raid into Ohio. By January, Young escaped captivity and fled to Canada. On October 10, Bennett crossed the Canadian border with two others, taking a room at the Tremont House, in St. Albans. The trio claimed they had come for a “sporting vacation”.

Small groups filtered into St. Albans in the following days, quietly taking rooms across the town. There were 21 altogether, former POWs and cavalrymen, hand selected by Young for their daring and resourcefulness.

On October 19, 1864, the group sprang into action. Splitting into four groups and declaring themselves Confederate soldiers, the groups simultaneously robbed three of St. Albans’ four banks while eight or nine held the townspeople at gunpoint, on the village green. One resident was killed before it was over and another wounded. Young ordered his troops to burn the town, but bottles of “Greek Fire” carried for the purpose, failed to ignite. Only one barn was burned down and the group got away with a total of $208,000, and all the horses they could muster. It was the northernmost Confederate action by land, of the Civil War.

The group was arrested on crossing the border and held in Montreal. The Lincoln administration sought extradition but Canadian courts decided otherwise, ruling that the raiders were under military orders at the time and neutral Canada could not extradite them to America. The $88,000 found with the raiders, was returned.

American sensibilities were outraged. At least, those in the north. The Chicago Tribune urged the Northern states to invade, to “…take Canada by the throat and throttle her as a St. Bernard would a poodle pup.” President Abraham Lincoln announced that our neighbors to the north would now be required to produce passports, to travel south. The Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 abolishing duties on cross-border imports, was abolished.

33 delegates were in Quebec City at this time, deadlocked over the Maritime Provinces’ objections to the proceedings.

Upper Canadian politician John A Macdonald declared, “For the sake of securing peace to ourselves and our posterity we must make ourselves powerful…The great security for peace is to convince the world of our strength by being united.” MacDonald, the only member of the Quebec Conference with a background in constitutional law drafted 50 of the 72 resolutions, emerging from the meeting.

So it is a Confederate robbery of a Vermont bank provided the final impetus, toward a united Canada. The dominion of Canada was established on July 1, 1867.

The million dollars the Confederate government sank into its Canadian office, probably did more harm than good. Those resources could have been put to better use, but we have the advantage of hindsight. Neither Captain Hines nor Jefferson Davis could know how their story would turn out. In the end, both men fell victim to that greatest of human weaknesses: of believing to be true, that which they wanted to believe.

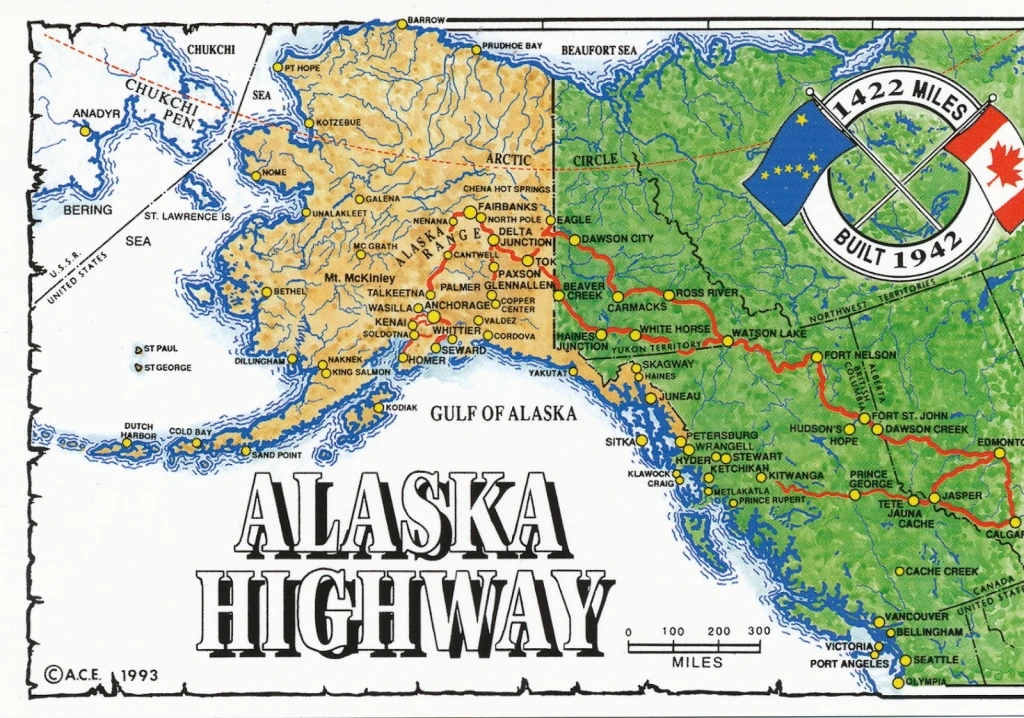

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC.

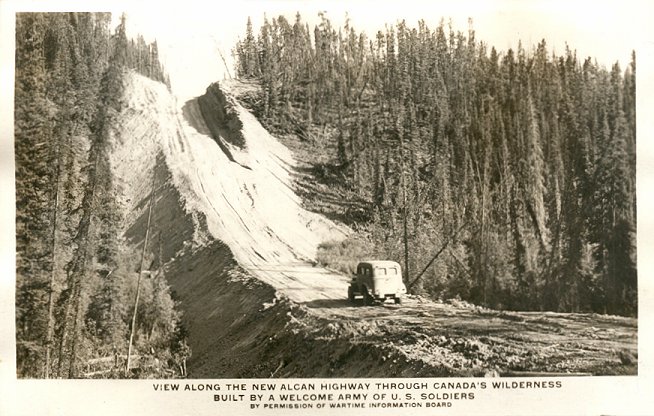

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC. Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food.

Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food.

NPR ran an interview about this story back in the eighties, in which an Inupiaq elder was recounting his memories. He had grown up in a world as it existed for hundreds of years, without so much as an idea of internal combustion. He spoke of the day that he first heard the sound of an engine, and went out to see a giant bulldozer making its way over the permafrost. The bulldozer was being driven by a black operator, probably one of the 97th Engineers Battalion soldiers. The old man’s comment, as best I can remember it, was a classic. “It turned out”, he said, “that the first white person I ever saw, was a black man”.

NPR ran an interview about this story back in the eighties, in which an Inupiaq elder was recounting his memories. He had grown up in a world as it existed for hundreds of years, without so much as an idea of internal combustion. He spoke of the day that he first heard the sound of an engine, and went out to see a giant bulldozer making its way over the permafrost. The bulldozer was being driven by a black operator, probably one of the 97th Engineers Battalion soldiers. The old man’s comment, as best I can remember it, was a classic. “It turned out”, he said, “that the first white person I ever saw, was a black man”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.