In 1915, Albert Marr and his family lived at a farm called Cheshire just outside Pretoria, South Africa. It was there that he found a small Chacma baboon and adopted the monkey, as a pet. He called the animal, “Jackie”.

The Great War had not yet reached it second year when Marr was sworn into the 3rd (Transvaal) Regiment of the 1st South African Infantry Brigade. He was now Private Albert Marr, #4927.

Private Marr asked for permission to bring Jackie along. Mascots are good for morale in times of war, a fact about which military authorities, were well aware.

To Marr’s great surprise, permission was granted. It wasn’t long before Jackie became the official Regimental Mascot.

Jackie drew rations like any other soldier, eating at the mess table, using his knife and fork and washing it all down with his own drinking basin. He even knew how to use a teacup.

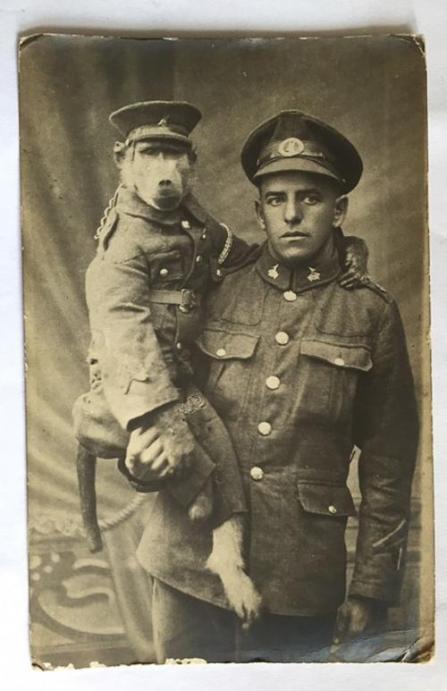

Jackie drilled and marched with his company in a special uniform and cap complete with buttons, regimental badges, and a hole for his tail.

He would entertain the men during quiet periods, lighting their pipes and cigarettes and saluting officers as they passed on their rounds. He learned to stand at ease when ordered, placing his feet apart and hands behind his back, regimental style.

These two inseparable buddies, Albert Marr and Jackie, first saw combat during the Senussi Campaign in North Africa. On February 26, 1916, Albert took a bullet in the shoulder at the Battle of Agagia. The monkey, beside himself with agitation, licked the wound and did everything he could to comfort the stricken man. It was this incident more than any other that marked Jackie’s transformation from pet and mascot, to a full-fledged member and comrade, of the regiment.

Jackie would accompany Albert at night, on guard duty. Marr soon learned to trust Jackie’s keen eyesight and acute hearing. The monkey was almost always first to know about enemy movements or impending attack, sounding an early warning with a series of sharp barks, or by pulling on Marr’s tunic.

The pair went through the nightmare of Delville Wood together early in the Somme campaign, when the First South African Infantry held its position despite eighty percent casualties.

The third Battle of Ypres, known as the battle of Passchendaele, began in the early morning hours of July 31, 1917. The pair experienced the sucking, nightmare mud of that place and the desperate fighting, around Kemmel Hill. The two were at Belleau Wood, a mostly American operation in which Marine Captain Lloyd Williams of the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, was famously informed he was surrounded, by Germans. “Retreat?” Williams snorted, “hell, we just got here.”

Through all of it, Marr and Jackie come through World War 1 mostly unscathed. That all changed in April, 1918.

Withdrawing through the West Flanders region of Belgium, the South African brigade came under heavy bombardment. Jackie was frantically building a wall of stones around himself, a shelter from the hammer blow concussion of the shells and the storm of flying metal buzzing through the air, as angry hornets. A jagged piece of shrapnel wounded Jackie’s arm and another all but tore off the animal’s leg. Even then, Jackie refused to be carried off by the stretcher-bearers, trying instead to finish his wall as he hobbled about on the bloody stump which had once been, his leg.

Lt. Colonel R. N. Woodsend of the Royal Medical Corps described the scene: “It was a pathetic sight; the little fellow, carried by his keeper, lay moaning in pain, the man crying his eyes out in sympathy, ‘You must do something for him, he saved my life in Egypt. He nursed me through dysentery’. The baboon was badly wounded, the left leg hanging with shreds of muscle, another jagged wound in the right arm. We decided to give the patient chloroform and dress his wounds…It was a simple matter to amputate the leg with scissors and I cleaned the wounds and dressed them as well as I could. He came around as quickly as he went under. The problem then was what to do with him. This was soon settled by his keeper: ‘He is on army strength’. So, duly labelled, number, name, ATS injection, nature of injuries, etc. he was taken to the road and sent by a passing ambulance to the Casualty Clearing Station”.

No one was quite sure that the chloroform used for the operation, wouldn’t kill him. When the officer commanding the regiment went to the aid station to check on him Jackie sat up in bed, and saluted.

As the “War to End All Wars” drew to a close, Jackie was promoted to the rank of Corporal and given a medal, for bravery. He may be the only monkey in history, ever to be so honored.

The war ended that November. Jackie and Albert were shipped to England and soon became, media celebrities. The two were hugely successful raising money for the widows and orphans fund, where members of the public could shake Jackie’s hand for half a crown. A kiss on the baboon’s cheek, would cost you five shillings.

On his arm he wore a gold wound stripe and three blue service chevrons, one for each of his three years’ front line service.

Jackie was the center of attention on arriving home to South Africa when a parade was held, officially welcoming the Regiment home. On July 31, 1920, Jackie received the Pretoria Citizen’s Service Medal, at the Peace Parade in Church Square, Pretoria.

All thing must come to an end. The Marr family farm burned to the ground in May 1921. Jackie died in the fire. Albert Marr lived to the age of 84 and passed away, in 1973. There wasn’t a day in-between when the man didn’t miss his little battle buddy Jackie, the baboon who went to war.

To the Central Powers, such trade had the sole purpose of killing their boys, fighting for the Fatherland on the battlefields of Europe.

To the Central Powers, such trade had the sole purpose of killing their boys, fighting for the Fatherland on the battlefields of Europe.

Known fatalities in the explosion included a Jersey City police officer, a Lehigh Valley Railroad Chief of Police, a ten week old infant, and the barge captain.

Known fatalities in the explosion included a Jersey City police officer, a Lehigh Valley Railroad Chief of Police, a ten week old infant, and the barge captain.

You must be logged in to post a comment.