In June 1812, neither the United States nor the British Empire were prepared for war. Most of the British war machine was busy with a “Little Corporal” whose “Waterloo” lay two years into in an uncertain future.

The Fledgling United States had only just disbanded the National Bank and now had no means of paying for war, while private northeastern bankers were reluctant to provide financing.

Support for the War of 1812 was bitterly divided, between the Democratic-Republicans of President James Madison, and the Federalist strongholds of Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Of the six New England states, New Hampshire alone complied with President Madison’s requests for state militia.

It may have been the most unpopular war in United States’ history. Much of New England threatened to secede, their position bolstered by the sack of Washington in August, 1814.

New England may have followed through with secession following the Hartford Convention of 1814, had not the Federalist position been made risible by future President Andrew Jackson’s overwhelming victory at the Battle of New Orleans.

Hartford Convention delegates ended with a formal report, resolutions from which would resurface decades later in a doctrine we know as nullification.

Opposition to America’s first declared war was vehement, and often bloody. Four days after it began, the office of the Baltimore Federal Republican newspaper was burned to the ground by an angry mob, infuriated by the anti-war editorials of Alexander Contee Hanson.

Hanson reopened his paper a month later, shielded by Revolutionary War veterans James Lingan and “Lighthorse Harry Lee”, father of Civil War General Robert E. Lee. The armed protection did him little good. Another mob formed within hours, this time torturing and severely beating Hanson, Lignan and Lee, before leaving them for dead.

James Lignan died of his injuries. Hanson recovered and went on to serve in the House of Representatives. Lee survived the beating but remained partially blind from hot wax poured into his eyes by the mob.

Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake claimed 200 years later, that, “Our city has a long history of peaceful demonstrations.” With all due respect to Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, Baltimore has been known as “Mobtown”, for at least that long.

The war of 1812 was fought in a series of land and sea battles along three fronts: The Atlantic Ocean & East Coast, the Southern States, and the Great Lakes & Canadian Frontier.

The British Navy had virtually unchallenged control of the Great Lakes in 1812, with several warships already on station. The only American warship on Lake Erie was the brig USS Adams, pinned down in Detroit and not yet fitted for service.

Detroit fell almost immediately and remained in British hands for over a year. The Adams was captured along with the town and renamed “HMS Detroit”.

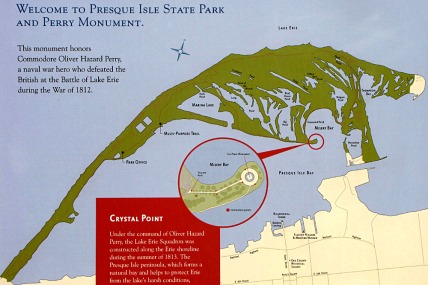

Meanwhile, Americans captured an English brig, the Caledonia, and acquired three civilian vessels, the schooners Somers and Ohio and the sloop-rigged Trippe. All four were converted into warships, which Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry had towed by oxen up the Niagara River. The operation which took six days. Once in Lake Erie they sailed down the coast to Presque Isle, on the Pennsylvania coast.

Chesapeake Bay and Pittsburgh foundries produced guns and fittings, while two more warships were ordered built at Presque Isle. Meanwhile, Perry drafted 50 experienced sailors from USS Constitution, then undergoing refit in Boston Harbor.

The American squadron was almost complete by mid-July, but there was a problem. The sand bar at the mouth of Presque Isle Bay is only 5-feet deep. This sand bar kept the British blockade at bay, with a little help from 2,000 Pennsylvania militia and several shore batteries. Once ready though, American ships had to contend with the same obstacle.

British Commander Robert Heriot Barclay was forced to lift his blockade on July 29, due to a supply shortage and bad weather. Perry immediately began the exhausting process of moving his vessels across the sandbar. Guns had to be removed, the larger boats raised between “camels”: barges lashed together and emptied of ballast to lift the ships high in the water. When Barclay returned four days later, he found the Americans had nearly completed the task.

What followed was one of history’s great head fakes. Naval warfare in the age of sail was typically conducted by two parallel lines of ships, pounding one another with cannon until one side could no longer take the punishment. Perry’s largest brigs were unready when the British fleet returned, yet the American gunboats formed into line of battle so quickly and with such confidence, that Barclay withdrew to await completion of HMS Detroit.

Perry’s fleet established anchorage at Put-in-Bay on the Ohio coast. It was there that Barclay’s fleet came for them on September 10.

Battle lines converged outside the harbor shortly after 11:00am. Perry’s flagship USS Lawrence took a savage beating, the longer guns of HMS Detroit having 20 minutes to do their work before Lawrence could effectively reply.

HMS Queen Charlotte added her gunfire to that of Detroit. Soon the American flagship was a wreck, with 80% casualties. Perry transferred his flag and rowed to the USS Niagara half a mile away, the brig being almost unscathed in the action, up to this point.

Damaged masts and rigging on the British side resulted in collision between Detroit and Queen Charlotte. They were still snarled up as Niagara broke through the British line, pounding them with broadsides from 18 32-pounder carronades and two 12-pounder long guns. Smaller English ships attempted to flee but were quickly overtaken.

That afternoon American and English vessels, the latter now prizes of war, were anchored with hasty repairs already underway. Oliver Hazard Perry took an old envelope and scrawled his now famous message to future President William Henry Harrison. “Dear General, We have met the enemy and they are ours. Two ships, two brigs, one schooner and one sloop. Yours with great respect and esteem, O.H. Perry“.

Niagara remains in service to this day, a Coast Guard sail trainer and outdoor exhibit for the Erie Maritime Museum. One of the last surviving ships, from the War of 1812.

The monarchical powers of Europe were quick to intervene. For the 32nd time since the Norman invasion of 1066, England and France once again found themselves in a state of war.

The monarchical powers of Europe were quick to intervene. For the 32nd time since the Norman invasion of 1066, England and France once again found themselves in a state of war.

Humphreys then used a hailing trumpet and ordered the American ship to comply, to which Barron responded “I don’t hear what you say”. Humphreys fired two rounds across Chesapeake’s bow, followed immediately by four broadsides.

Humphreys then used a hailing trumpet and ordered the American ship to comply, to which Barron responded “I don’t hear what you say”. Humphreys fired two rounds across Chesapeake’s bow, followed immediately by four broadsides.

United States Naval Captain James Lawrence was eager to comply, confident in the wake of a number of American victories in single-ship actions.

United States Naval Captain James Lawrence was eager to comply, confident in the wake of a number of American victories in single-ship actions.

The American public was outraged and there were calls for war in 1807, when HMS Leopard overtook the USS Chesapeake, kidnapping three American-born sailors and one British deserter, leaving another three dead and 18 wounded.

The American public was outraged and there were calls for war in 1807, when HMS Leopard overtook the USS Chesapeake, kidnapping three American-born sailors and one British deserter, leaving another three dead and 18 wounded. Outside of the British Royal Navy, the practice of kidnapping people to serve as shipboard labor was known as “crimping”. Low wages combined with the gold rushes of the 19th century left the waterfront painfully short of manpower, skilled and unskilled, alike. “Boarding Masters” had the job of putting together ship’s crews, and were paid for each recruit. There was strong incentive to produce as many able bodies, as possible. Unwilling men were “shanghaied” by means of trickery, intimidation or violence, most often rendered unconscious and delivered to waiting ships, for a fee.

Outside of the British Royal Navy, the practice of kidnapping people to serve as shipboard labor was known as “crimping”. Low wages combined with the gold rushes of the 19th century left the waterfront painfully short of manpower, skilled and unskilled, alike. “Boarding Masters” had the job of putting together ship’s crews, and were paid for each recruit. There was strong incentive to produce as many able bodies, as possible. Unwilling men were “shanghaied” by means of trickery, intimidation or violence, most often rendered unconscious and delivered to waiting ships, for a fee.

San Francisco political bosses William T. Higgins, (R) and Chris “Blind Boss” Buckley (D) were both notable crimps, and well positioned to look after their political interests. Notorious crimps such as Joseph “Frenchy” Franklin and George Lewis were elected to the California state legislature. There was no better spot, from which to ensure that no legislation would interfere with such a lucrative trade.

San Francisco political bosses William T. Higgins, (R) and Chris “Blind Boss” Buckley (D) were both notable crimps, and well positioned to look after their political interests. Notorious crimps such as Joseph “Frenchy” Franklin and George Lewis were elected to the California state legislature. There was no better spot, from which to ensure that no legislation would interfere with such a lucrative trade. Imagine the hangover the next morning, to wake up and find you’re now at sea, bound for somewhere in the far east. Regulars knew about the trap door and avoided it at all costs, knowing that anyone going over there, was “fair game”.

Imagine the hangover the next morning, to wake up and find you’re now at sea, bound for somewhere in the far east. Regulars knew about the trap door and avoided it at all costs, knowing that anyone going over there, was “fair game”.

Barbary pirates were a problem for Mediterranean shipping, and throughout parts of the Atlantic. Predominantly North African Muslims with the occasional outcast European, the Barbary pirates operated with the blessing of the Ottoman Empire, the Barbary Coast states of Algiers, Tunis & Tripoli, and the independent Sultanate of Morocco. The Barbary Corsairs had long since stripped the shorelines of Spain and Italy in search of loot and Christian slaves.

Barbary pirates were a problem for Mediterranean shipping, and throughout parts of the Atlantic. Predominantly North African Muslims with the occasional outcast European, the Barbary pirates operated with the blessing of the Ottoman Empire, the Barbary Coast states of Algiers, Tunis & Tripoli, and the independent Sultanate of Morocco. The Barbary Corsairs had long since stripped the shorelines of Spain and Italy in search of loot and Christian slaves. Constitution’s first duties involved the “quasi-war” with France, but this was not the France which helped us win our independence. France had been swallowed up in a revolution of its own by this time. Leftists calling themselves “Jacobins” had long since sent their Bourbon King and his Queen Consort to the guillotine. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier,

Constitution’s first duties involved the “quasi-war” with France, but this was not the France which helped us win our independence. France had been swallowed up in a revolution of its own by this time. Leftists calling themselves “Jacobins” had long since sent their Bourbon King and his Queen Consort to the guillotine. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier,  Two months after the War of 1812 broke out in June, Constitution faced off with the 38 gun HMS Guerriere, about 400 miles off the coast of Halifax. Watching Guerriere’s shots bounce off Constitution’s 21” thick oak hull, an American sailor exclaimed “Huzzah! her sides are made of iron!” Guerriere was reduced to an unsalvageable hulk in twenty minutes, and the nickname “Old Ironsides” was born.

Two months after the War of 1812 broke out in June, Constitution faced off with the 38 gun HMS Guerriere, about 400 miles off the coast of Halifax. Watching Guerriere’s shots bounce off Constitution’s 21” thick oak hull, an American sailor exclaimed “Huzzah! her sides are made of iron!” Guerriere was reduced to an unsalvageable hulk in twenty minutes, and the nickname “Old Ironsides” was born.

Perry’s fleet established anchorage at Put-in-Bay on the Ohio coast. It was there that Barclay’s fleet came for them on September 10.

Perry’s fleet established anchorage at Put-in-Bay on the Ohio coast. It was there that Barclay’s fleet came for them on September 10.

The Corsican’s defeat at Waterloo and subsequent exile to Elba freed up some of the most elite, battle hardened troops in the world.

The Corsican’s defeat at Waterloo and subsequent exile to Elba freed up some of the most elite, battle hardened troops in the world.

General Ross sent two hundred men to secure a fort on Greenleaf’s Point. The fort had already been destroyed by American forces, but 150 barrels of gunpowder remained. The powder ignited while the British were trying to drop it into a well, killing at least a dozen and injuring many others.

General Ross sent two hundred men to secure a fort on Greenleaf’s Point. The fort had already been destroyed by American forces, but 150 barrels of gunpowder remained. The powder ignited while the British were trying to drop it into a well, killing at least a dozen and injuring many others.

You must be logged in to post a comment.