On June 25, 1950, ten divisions of the North Korean People’s Army (KPA) launched a surprise invasion of their neighbor to the south. The 38,000-man army of the Republic of Korea (ROK) didn’t have a chance against 89,000 men sweeping down in six columns from the north. Within hours, the shattered remnants of the Republic of Korea Army and its government were retreating south toward their capital of Seoul.

The UN security council voted to send troops to the Korean peninsula.

Poorly prepared and under-strength for what they were about to face, units of the 24th Division United States Army were hastily sent from bases in Japan. It was not until August when General Douglas MacArthur’s forces in theater, designated United Nations Command (UNC), was able to slow and finally stop North Korean forces around the vital southern port city of Pusan.

American forces and ROKA defenders were in danger of being hurled into the sea. Most of the KPA was committed to doing just that, as plans were hastily drawn up for an amphibious landing on Inch’ŏn, the port outlet for the South Korean capital of Seoul.

With a narrow, labyrinthine channel and a tidal variation of nearly 30-feet, Inch’ŏn was a terrible choice for a major amphibious landing, with no more than a six-hour window permitting use of the beaches.

The Inch’ŏn landing was one of the great operations in military history, recapturing the capital and all but destroying North Korean military operations in the South. Meanwhile, a storm was building north of the border, in the form of a quarter-million front-line Chinese troops, assembling in Manchuria.

The war seemed all but over in October as UNC forces streamed into the north, the US 8th Army to the west of the impassable Taebaek mountains, the ROK I Corps and US X Corps to the east, reinforced by the US 1st Marine landing at Wonsan. North and South would be reunited by the end of the year, and everyone would be home by Christmas.

Except, that’s not how things worked out.

By the end of November, 30,000 UN troops were spread along a 400-mile line near the Chosin Reservoir, all but overrun and fighting for their lives against 150,000 Chinese forces of the “People’s Volunteer Army (PVA).

Weather conditions were savage at the “Frozen Chosin”, a Siberian cold front dropping day-time highs to -5° Fahrenheit, with lows exceeding -25°. Vehicles and radios failed to start in the cold. Medical supplies froze. Morphine syrettes had to be thawed in the medic’s mouth, prior to use. Frozen blood plasma was useless. Just to cut off clothing to deal with a wound, risked frostbite. Perhaps worst of all, gun lubricants turned to gel and springs froze. There must be no more demoralizing sound in combat than the impotent click of a firing pin, too weak to work.

Clifford Meyer remembers: “During November 1950 the First Marine Division with elements of two Regimental combat teams of the U.S. Army, a Detachment of British Commandos and some South Korean Policemen — about 15,000 men — faced the Chinese Communist Army’s ten Divisions totaling 120,000 men. At a mountain reservoir called Chang Jin (we called it “Chosin”) temperatures ranged from minus five degrees below zero in the day to minus twenty-five degrees below zero at night. The ground froze so hard that bulldozers could not dig emplacements for our Artillery. The cold impeded our weapons from firing automatically, slowing down the recoil of our artillery and automatic weapons. The cold numbed our minds, froze our fingers and toes and froze our rations. [We were] seventy-eight miles from the sea, surrounded, supplies cut, facing an enemy whose sole objective was the annihilation of the First Marine Division as a warning to other United Nations troops, and written off as lost by the high command“.

The PVA launched multiple attacks and ambushes over the night of November 27. The “Chosin Few” were all but surrounded by the morning of the twenty-eighth, locked in a fight for their lives.

Over two weeks of bitter combat, fifteen thousand soldiers and Marines fought their way over seventy-eight miles of gravel road, back to the sea. One war correspondent asked 1st Marine General Oliver Prince Smith if they were retreating. “Retreat? Hell”, Smith said, “we are attacking in another direction”.

Survival depended on air drops from US Navy Task Force 77 running 230 forays per day providing close-air support, food, medicine & combat supplies, and US Air Force Far East Combat Cargo Command in Japan, airdropping 250-tons of supplies. Every day.

Everything had a code name to throw off Chinese anti-aircraft units. Marines sent out a frantic call for 60-mm mortar ammunition, code named “Tootsie Rolls”. Somebody didn’t read up on his code book. Fighting for their lives in the frozen wastes of Chosin, that’s what they got. Chocolate candy. By the ton.

What at first seemed a screw-up of biblical proportions, soon proved a blessing in disguise. With no way to build a fire and frozen rations unusable, those Tootsie rolls were all that stood between survival and starvation. 15,000 soldiers and Marines suffered 12,000 casualties before it was over: 3,000 dead, 6,000 wounded and thousands of frostbite cases.

Untold thousands of Tootsie roll wrappers littered the seventy-eight miles back to the sea. Most credit their survival to the energy provided by the chocolate candy. It turns out that frozen tootsie rolls make a swell putty too, useful for patching up fractured hoses and vehicles.

The Korean War Gallery at the National Marine Corps Museum in Quantico features a lone Marine, 30-mm machine gun at the ready, marching out of the frozen wastes of the Chosin reservoir. There’s a paper candy wrapper in the snow at his feet. Though age has diminished their numbers, the “Chosin Few” still get together, for the occasional reunion. Tootsie Roll Industries has always sent the candy and continues to do so, to this day.

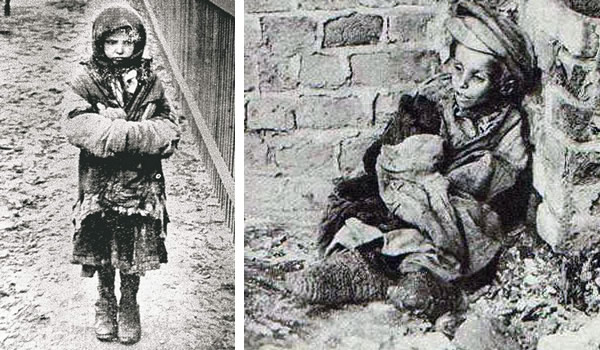

Armed “dekulakization brigades” confiscated land, livestock and other property by force, evicting entire families. Nearly half a million individuals were dragged from their homes in 1930-’31 alone, packed into freight trains and shipped off to remote areas like Siberia and often left without food or shelter. Many of them, especially children, died in transit or soon after arrival.

Armed “dekulakization brigades” confiscated land, livestock and other property by force, evicting entire families. Nearly half a million individuals were dragged from their homes in 1930-’31 alone, packed into freight trains and shipped off to remote areas like Siberia and often left without food or shelter. Many of them, especially children, died in transit or soon after arrival.

At the height of the famine, Ukrainians starved to death at a rate of 22,000 per day, almost a third of those, children 10 and under. How many died in total, is anyone’s guess. Estimates range from two million Ukrainian citizens murdered by their own government, to well over ten million.

At the height of the famine, Ukrainians starved to death at a rate of 22,000 per day, almost a third of those, children 10 and under. How many died in total, is anyone’s guess. Estimates range from two million Ukrainian citizens murdered by their own government, to well over ten million.

To this day, the New York Times has failed to repudiate Walter Duranty’s Pulitzer.

To this day, the New York Times has failed to repudiate Walter Duranty’s Pulitzer. To do so at all was an act of courage. single Jewish woman who’d lost part of a leg in a childhood streetcar accident, traveling to a place where the Russian empire and its successor state had a long and wretched history. Particularly when it came to the treatment of its own Jews.

To do so at all was an act of courage. single Jewish woman who’d lost part of a leg in a childhood streetcar accident, traveling to a place where the Russian empire and its successor state had a long and wretched history. Particularly when it came to the treatment of its own Jews.

The Holodomor Memorial to Victims of the Ukrainian Famine-Genocide of 1932–1933 was opened in Washington, D.C. on November 7, 2015

The Holodomor Memorial to Victims of the Ukrainian Famine-Genocide of 1932–1933 was opened in Washington, D.C. on November 7, 2015

You must be logged in to post a comment.