In 1928, Soviet Dictator Josef Stalin introduced a program of agricultural collectivization in Ukraine, the “Bread Basket” of the Soviet Union, forcing family farmers off their land and into state-owned collective farms.

Ukrainian “kulaks”, peasant farmers successful enough to hire labor or own farm machinery, refused to join the collectives, regarding such as a return to the serfdom of earlier centuries. Stalin claimed that these factory collectives would not only feed industrial workers in the cities, but would also provide a surplus to be sold abroad, raising money to further his industrialization plans.

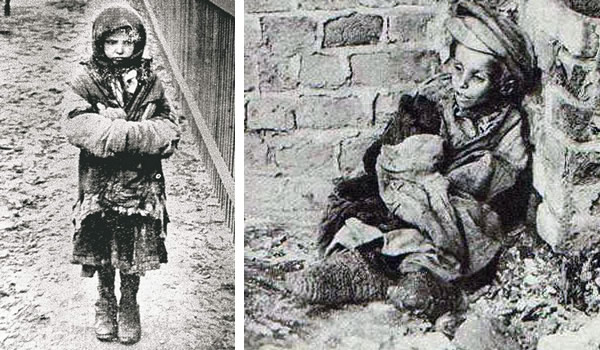

Armed “dekulakization brigades” confiscated land, livestock and other property by force, evicting entire families. Nearly half a million individuals were dragged from their homes in 1930-’31 alone, packed into freight trains and shipped off to remote areas like Siberia and often left without food or shelter. Many of them, especially children, died in transit or soon after arrival.

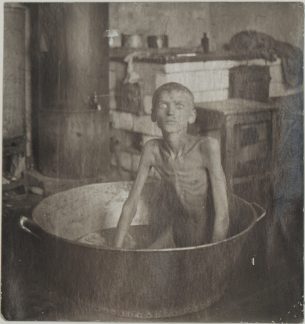

Resistance continued, which the Soviet government could not abide. Ukraine’s production quotas were sharply increased in 1932-’33, making it impossible for farmers to meet assignments and feed themselves, at the same time. Starvation became widespread, as the Soviet government decreed that any person, even a child, would be arrested for taking as little as a few stalks of wheat from the fields in which they worked.

Military blockades were erected around villages preventing the transportation of food, while brigades of young activists from other regions were brought in to sweep through villages and confiscate hidden grain.

Warm and well fed with Russian mistress comfortably ensconced in Moscow, French wife hidden away on the Riviera, the British born New York Times Times reporter-turned international playboy opined, “You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.”

Walter Duranty, New York Times

Eventually all food was confiscated from farmers’ homes, as Stalin determined to “teach a lesson through famine” to the Ukrainian rural population.

At the height of the famine, Ukrainians starved to death at a rate of 22,000 per day, almost a third of those, children 10 and under. How many died in total, is anyone’s guess. Estimates range from two million Ukrainian citizens murdered by their own government, to well over ten million.

Millions of tons of grain were exported during this time, more than enough to save every man, woman and child.

2,500 people were arrested and convicted during this time, for eating the flesh of their neighbors. The problem was so widespread that the Soviet government put up signs reminding survivors: “To eat your own children is a barbarian act.”

Stalin denied to the world there was any famine in Ukraine, a position supported by the likes of Louis Fischer reporting for “The Nation”, and Walter Duranty of the New York Times. Duranty went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for his “coverage”, with comments like “any report of a famine in Russia is today an exaggeration or malignant propaganda”. Such stories were “mostly bunk,” according to the New York Times.

Warm and well fed with Russian mistress comfortably ensconced in Moscow, French wife hidden away on the Riviera, the British born New York Times Times reporter-turned international playboy opined, “You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.”

To this day, the New York Times has failed to repudiate Walter Duranty’s Pulitzer.

Like many on the international Left, Canadian journalist Rhea Clyman had great expectations of the “worker’s paradise” built by the Communist state, where no one was unemployed, everyone was “equal”, and Everyman had what he needed.

Unlike most, Clyman went to the Soviet Union to see for herself.

To do so at all was an act of courage. single Jewish woman who’d lost part of a leg in a childhood streetcar accident, traveling to a place where the Russian empire and its successor state had a long and wretched history. Particularly when it came to the treatment of its own Jews.

Virtually all of the international press preferred the comfortable confines of Moscow, cosseted in a world of Soviet propaganda and ignorant of the world as it was.

Duranty’s idea of “bon voyage” was the cynical offer, to write her obituary.Rhea Clyman

In four years, Clyman not only learned the language, but set out on a 5,000-mile odyssey to discover the Soviet countryside, as it really was.

It is through this “Special Correspondent in Russia of The Toronto Evening Telegram, London Daily Express, and Other Newspapers“, that we know much about the government’s extermination of its own citizens in Ukraine.

To read what Clyman wrote about abandoned villages, is haunting. The moment of discovery: “They wanted something of me, but I could not make out what it was. At last someone went off for a little crippled lad of fourteen, and when he came hobbling up, the mystery was explained. This was the Village of Isoomka, the lad told me. I was from Moscow, yes; we were a delegation studying conditions in the Ukraine, yes. Well, they wanted me to take a petition back to the Kremlin, from this village and the one I had just been in. “Tell the Kremlin we are starving; we have no bread!”

A tall, bearded peasant was spokesman. His two sons and the rest of the men and women nodded approval at every word. The little crippled boy stood with his right hand on his crutch, translating everything he said into Russian for me, word by word. “We are good, hard-working peasants, loyal Soviet citizens, but the village Soviet has taken our land from us. We are in the collective farm, but we do not get any grain. Everything, land, cows and horses, have been taken from us, and we have nothing to eat. Our children were eating grass in the spring….”

I must have looked unbelieving at this, for a tall, gaunt woman started to take the children’s clothes off. She undressed them one by one, prodded their sagging bellies, pointed to their spindly legs, ran her hand up and down their tortured, mis-shapen, twisted little bodies to make me understand that this was real famine. I shut my eyes, I could not bear to look at all this horror. “Yes,” the woman insisted, and the boy repeated, “they were down on all fours like animals, eating grass. There was nothing else for them.” What have you to eat now?” I asked them, still keeping my eyes averted from those tortured bodies. “Are all the villages round here the same? Who gets the grain?”” – Rhea Clyman, Toronto Telegram, 16 May 1933

22,000 of these poor people starved to death, every day. Pitifully, many yet believed the government in Moscow was going to help. If only comrade Stalin knew…

The Holodomor Memorial to Victims of the Ukrainian Famine-Genocide of 1932–1933 was opened in Washington, D.C. on November 7, 2015

Today, the province of Alberta is home to about 300,000 Canadians of Ukrainian Heritage. Alberta Premier Rachel Notley once explained “Holodomor is a combination of two Ukrainian words: Holod, meaning hunger, and moryty, meaning a slow, cruel death. That is exactly what Ukrainians suffered during this deliberate starvation of an entire people“.

Ukrainians around the world recognize November 23 as Holodomor Memorial Day, commemorated by a simple statue in Kiev. A barefoot little girl, gaunt and hollow eyed, clutches a few stalks of wheat.Holodomor memorial. The Holodomor was a man-made famine in the Ukrainian SSR between 1932 and 1933. During the famine, 2.4 – 7.5 millions of Ukrainians died of starvation.

Here in the United States, you could line up 100 randomly selected adults. I don’t believe that five could tell you what Holodomor even means. We are a self-governing Republic. All 100 should be well acquainted with the term

Armed “dekulakization brigades” confiscated land, livestock and other property by force, evicting entire families. Nearly half a million individuals were dragged from their homes in 1930-’31 alone, packed into freight trains and shipped off to remote areas like Siberia and often left without food or shelter. Many of them, especially children, died in transit or soon after arrival.

Armed “dekulakization brigades” confiscated land, livestock and other property by force, evicting entire families. Nearly half a million individuals were dragged from their homes in 1930-’31 alone, packed into freight trains and shipped off to remote areas like Siberia and often left without food or shelter. Many of them, especially children, died in transit or soon after arrival. At the height of the famine, Ukrainians starved to death at a rate of 22,000 per day, almost a third of those, children 10 and under. How many died in total, is anyone’s guess. Estimates range from two million Ukrainian citizens murdered by their own government, to well over ten million.

At the height of the famine, Ukrainians starved to death at a rate of 22,000 per day, almost a third of those, children 10 and under. How many died in total, is anyone’s guess. Estimates range from two million Ukrainian citizens murdered by their own government, to well over ten million. To this day, the New York Times has failed to repudiate Walter Duranty’s Pulitzer.

To this day, the New York Times has failed to repudiate Walter Duranty’s Pulitzer. To do so at all was an act of courage. single Jewish woman who’d lost part of a leg in a childhood streetcar accident, traveling to a place where the Russian empire and its successor state had a long and wretched history. Particularly when it came to the treatment of its own Jews.

To do so at all was an act of courage. single Jewish woman who’d lost part of a leg in a childhood streetcar accident, traveling to a place where the Russian empire and its successor state had a long and wretched history. Particularly when it came to the treatment of its own Jews. The Holodomor Memorial to Victims of the Ukrainian Famine-Genocide of 1932–1933 was opened in Washington, D.C. on November 7, 2015

The Holodomor Memorial to Victims of the Ukrainian Famine-Genocide of 1932–1933 was opened in Washington, D.C. on November 7, 2015

Armed dekulakization brigades confiscated land, livestock and other property by force, evicting entire families. Nearly half a million individuals were dragged from their homes in 1930-’31 alone, packed into freight trains and shipped off to remote areas like Siberia and often left without food or shelter. Many of them, especially children, died in transit or soon after arrival.

Armed dekulakization brigades confiscated land, livestock and other property by force, evicting entire families. Nearly half a million individuals were dragged from their homes in 1930-’31 alone, packed into freight trains and shipped off to remote areas like Siberia and often left without food or shelter. Many of them, especially children, died in transit or soon after arrival. Military blockades were erected around villages preventing the transportation of food, while brigades of young activists from other regions were brought in to sweep through villages and confiscate hidden grain.

Military blockades were erected around villages preventing the transportation of food, while brigades of young activists from other regions were brought in to sweep through villages and confiscate hidden grain. At the height of the famine, Ukrainians starved to death at a rate of 22,000 per day, almost a third of those, children 10 and under. How many died in total, is anyone’s guess. Estimates range from two million Ukrainian citizens murdered by their own government, to well over ten million.

At the height of the famine, Ukrainians starved to death at a rate of 22,000 per day, almost a third of those, children 10 and under. How many died in total, is anyone’s guess. Estimates range from two million Ukrainian citizens murdered by their own government, to well over ten million. 2,500 people were arrested and convicted during this time, for eating the flesh of their neighbors. The problem was so widespread that the Soviet government put up signs reminding survivors: “To eat your own children is a barbarian act.”

2,500 people were arrested and convicted during this time, for eating the flesh of their neighbors. The problem was so widespread that the Soviet government put up signs reminding survivors: “To eat your own children is a barbarian act.” To this day, the New York Times has failed to repudiate Walter Duranty’s Pulitzer.

To this day, the New York Times has failed to repudiate Walter Duranty’s Pulitzer. To do so at all was an act of courage. single Jewish woman who’d lost part of a leg in a childhood streetcar accident, traveling to a place where the Russian empire and its successor state had a long and wretched history. Particularly when it came to the treatment of its own Jews.

To do so at all was an act of courage. single Jewish woman who’d lost part of a leg in a childhood streetcar accident, traveling to a place where the Russian empire and its successor state had a long and wretched history. Particularly when it came to the treatment of its own Jews.

The Holodomor Memorial to Victims of the Ukrainian Famine-Genocide of 1932–1933 was opened in Washington, D.C. on November 7, 2015

The Holodomor Memorial to Victims of the Ukrainian Famine-Genocide of 1932–1933 was opened in Washington, D.C. on November 7, 2015

A tall, bearded peasant was spokesman. His two sons and the rest of the men and women nodded approval at every word. The little crippled boy stood with his right hand on his crutch, translating everything he said into Russian for me, word by word.

A tall, bearded peasant was spokesman. His two sons and the rest of the men and women nodded approval at every word. The little crippled boy stood with his right hand on his crutch, translating everything he said into Russian for me, word by word.

As Stalin’s Soviet Union imposed the “terror famine” of 1932-’33, the deliberate starvation of millions of Ukrainian peasant farmers known as the

As Stalin’s Soviet Union imposed the “terror famine” of 1932-’33, the deliberate starvation of millions of Ukrainian peasant farmers known as the  As director of the Soviet Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Lysenko put his theories to work, with unsurprisingly dismal results. He’d force Soviet farmers to plant WAY too close together, on the theory that plants of the same “class” would “cooperate” with one another, and that “mutual assistance” takes place within and even across plant species.

As director of the Soviet Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Lysenko put his theories to work, with unsurprisingly dismal results. He’d force Soviet farmers to plant WAY too close together, on the theory that plants of the same “class” would “cooperate” with one another, and that “mutual assistance” takes place within and even across plant species.

By the siege’s end in the Spring of 1944, nine of them had starved to death, standing watch over all that food. These guys had stood guard over their seed bank for twenty-eight months, without eating so much as a grain.

By the siege’s end in the Spring of 1944, nine of them had starved to death, standing watch over all that food. These guys had stood guard over their seed bank for twenty-eight months, without eating so much as a grain.

In the “Killing Fields” of 1975-’79 Cambodia, Pol Pot and a cadre of nine or so individuals, the Ang-Ka, led the Khmer Rouge in the extermination of between 1.7 and 2.5 million, in a country of barely 8 million.

In the “Killing Fields” of 1975-’79 Cambodia, Pol Pot and a cadre of nine or so individuals, the Ang-Ka, led the Khmer Rouge in the extermination of between 1.7 and 2.5 million, in a country of barely 8 million. Many Ukrainian farmers refused to join the collectives, regarding them as a return to the serfdom of earlier centuries. Stalin introduced “class warfare”, that age old bugaboo of the Left, to break down resistance to collectivization.

Many Ukrainian farmers refused to join the collectives, regarding them as a return to the serfdom of earlier centuries. Stalin introduced “class warfare”, that age old bugaboo of the Left, to break down resistance to collectivization. Eventually all food was confiscated from farmers’ homes, as Stalin determined to “teach a lesson through famine” to the backbone of the region, the rural population of Ukraine.

Eventually all food was confiscated from farmers’ homes, as Stalin determined to “teach a lesson through famine” to the backbone of the region, the rural population of Ukraine.

You must be logged in to post a comment.