From the earliest years of the “new world” period, every economy from Canada to Argentina was, to varying degrees, involved with slavery. Spanish and Portuguese settlers brought the first African slaves to the Americas in 1501, establishing the new world’s first international slave port in Santo Domingo, modern capital city of the Dominican Republic.

Hundreds of thousands of Africans entered the Americas through the sister ports of Veracruz, Mexico, and Portobelo, Panama, “products” of the “Asiento” system wherein the contractor (asientista) was awarded a monopoly in the slave trade to Spanish colonies in exchange for royalties, paid to the crown.

The first such contractor was a Genoese company which agreed to supply 1,000 slaves over an 8-year period, beginning in 1517. A German company entered into such a contract eight years later with a pledge of 4,000.

By 1590, as many as 1.1 million Africans had come through the port of Cartagena, Colombia, sorted and surnamed under the “casta de nación” classification system.

In the American colonies, 17th century attitudes toward race appear to have been more fluid than they would later become. The first black Africans, 19 of them, came to the Virginia Colony in 1619 not as slaves, but as indentured servants. Their passage, involuntary as it was, was paid for by a term of indenture, a sort of ‘temporary slavery’, usually lasting seven years.

John Punch ran away from his term of indenture along with two Europeans, in 1640. The trio was captured in Maryland and sentenced to extended terms of indenture. Alone among the three, Punch was punished with indenture for life, effectively making him the first African ‘slave’ in the American colonies.

Meanwhile, black Africans both enslaved and free had arrived in the north American colonies, for nearly a hundred years.

Juan Garrido moved from the west coast of Africa to Lisbon, Portugal, possibly as a slave, or perhaps the son of an African King, sent for a Christian education. Be that as it may, Garrido came to the new world a free man in 1513, with Juan Ponce de León. A black Conquistador who spent thirty years with the conquest, “pacifying” indigenous peoples and searching for gold, and the mythical fountain of youth.

He was not alone. Other black Africans entered Spanish society as free men, and joining the conquest as soldiers. Some did so in exchange for freedom, some for land, official jobs, or public pensions. Ponce was fatally injured by a native arrow in 1521. Garrido went on to marry and settle in Mexico city, where he is credited with the first commercial cultivation of wheat, in the new world.

Twenty years before the “Lost” English colonists first landed at Roanoke, Pedro Menendez de Aviles founded St. Augustine, in the Spanish colony of Florida. Aviles’ colonial expedition included many black Africans, both free men and slaves, who remained a part of St. Augustine society, from that time forward. The first recorded birth in the New World of an American child of African descent took place in 1606 according to St. Augustine Catholic parish records, a year before the English settlement, at Jamestown.

The Spanish government in Florida began to offer asylum to slaves from British colonies as early as 1687, when eight men, two women and a three year old nursing child arrived there, seeking refuge. It probably wasn’t as altruistic as it sounds, given the history. The primary interest seems to have been disrupting the English agricultural economy, to the north.

The Florida governor required only that such runaways convert to Catholicism, and then he put the men to work for wages.

In 1693, King Charles of Spain officially proclaimed that runaways would find freedom in Florida, provided they would convert to Catholicism and perform four years of service to the Crown. Spain had effectively created a maroon colony (from the Spanish word cimarrón, meaning “fugitive, runaway”, literally “living on mountaintops”), forming a front-line defense against English attack, from the north.

Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mosé (pronounced “Moh-say”), was a military fortification two miles north of St. Augustine, established by Colonial Governor Manuel de Montiano, in 1738. Spanish militia would place incoming freedom seekers into military service at the fort, under the leadership of an African Creole man known as Francisco Menendez.

Fort Mosé was the first legally sanctioned free black settlement, in what would become the United States.

Long before the famous “underground railroad”, the first such track pointed not north, but south, to St. Augustine. Word of the settlement reached into Georgia and South Carolina to the north, attracting escaping slaves. It was probably the “final straw” that set off the unsuccessful 1739 slave insurrection known as the Stono Rebellion, in which several dozen runaway slaves attempted to reach Spanish Florida.

In the early phase of the War of Jenkins Ear, Fort Mosé was abandoned and occupied by General James Oglethorpe, colonial governor of Georgia, along with a force of British colonial rangers, Scottish Highlanders, enslaved black auxiliaries and native Creek and Uchise allies.

The British garrison was caught by surprise in the pre-dawn hours of June 16, 1740 and all but annihilated, by a force of Spanish soldiers, free black militia and native Yamasee allies. The coquina fortification was destroyed in the process, and would not be rebuilt until 1752.

In June of this year, Florida Living History, Inc. and the Fort Mosé Historical Society presented the latest in a series of re-enactments, celebrating the 277th anniversary of the “Bloody Battle of Fort Mosé “. The site has seen several archaeological excavations in recent years, and is considered the “premier site on the Florida Black Heritage Trail.” Fort Mosé was officially designated an Historic State Park on October 12, 1994.

2,500 years ago, Bantu farmers on the African continent began to spread out across the land as the first Africans penetrated the dense rain forests of the equator, to take up a new life on the west African coast.

2,500 years ago, Bantu farmers on the African continent began to spread out across the land as the first Africans penetrated the dense rain forests of the equator, to take up a new life on the west African coast.

Home to one of the few safe harbors on the surf-battered “windward coast”, Sierra Leone soon became a favorite of European mariners, some of whom remained for a time while others came to stay, intermarrying with local women.

Home to one of the few safe harbors on the surf-battered “windward coast”, Sierra Leone soon became a favorite of European mariners, some of whom remained for a time while others came to stay, intermarrying with local women. While this type of “slave” retained rudimentary rights at this time, those unfortunate enough to be captured by Dutch, English and French slavers, did not.

While this type of “slave” retained rudimentary rights at this time, those unfortunate enough to be captured by Dutch, English and French slavers, did not. This was the world of John Newton, born July 24 (old style) 1725 and destined to a life, in the slave trade.

This was the world of John Newton, born July 24 (old style) 1725 and destined to a life, in the slave trade. Newton hated life on the Pegasus as much as they, hated him. In 1745, they left him in West Africa with slave trader Amos Clowe. Newton was now himself a slave, given by Clowe to his wife Princess Peye of the Sherbro tribe. Peye treated Newton as horribly as any of her other slaves. Newton himself later described these three years as “once an infidel and a libertine, [now] a servant of slaves in West Africa”.

Newton hated life on the Pegasus as much as they, hated him. In 1745, they left him in West Africa with slave trader Amos Clowe. Newton was now himself a slave, given by Clowe to his wife Princess Peye of the Sherbro tribe. Peye treated Newton as horribly as any of her other slaves. Newton himself later described these three years as “once an infidel and a libertine, [now] a servant of slaves in West Africa”. Moving to London in 1780 as the Rector of St. Mary Woolnoth church, Newton became involved with the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

Moving to London in 1780 as the Rector of St. Mary Woolnoth church, Newton became involved with the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. William Cowper was an English poet and hymnist who came to worship in Newton’s church, in 1767. The pair collaborated on a book of Newton’s hymns including “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken,” “How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds!,” “Come, My Soul, Thy Suit Prepare” and others.

William Cowper was an English poet and hymnist who came to worship in Newton’s church, in 1767. The pair collaborated on a book of Newton’s hymns including “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken,” “How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds!,” “Come, My Soul, Thy Suit Prepare” and others.

Barack Obama wrote in his memoir “Dreams from my Father”, that his grandfather Hussein Onyango Obama was captured and tortured by British authorities during the Mau Mau uprising. The now-former President wrote that his father was “selected by Kenyan leaders and American sponsors to attend a university in the United States, joining the first large wave of Africans to be sent forth to master Western technology and bring it back to forge a new, modern Africa“.

Barack Obama wrote in his memoir “Dreams from my Father”, that his grandfather Hussein Onyango Obama was captured and tortured by British authorities during the Mau Mau uprising. The now-former President wrote that his father was “selected by Kenyan leaders and American sponsors to attend a university in the United States, joining the first large wave of Africans to be sent forth to master Western technology and bring it back to forge a new, modern Africa“. If you’re interested in a little pop culture sauce to go with this turkey, the Mau Mau uprising inspired a number of similar rebellions throughout the region. One of them occurred in the East African coastal city of Zanzibar.

If you’re interested in a little pop culture sauce to go with this turkey, the Mau Mau uprising inspired a number of similar rebellions throughout the region. One of them occurred in the East African coastal city of Zanzibar.

At the outset of the “Great War”, a map of Africa looked nothing like it does today. From the

At the outset of the “Great War”, a map of Africa looked nothing like it does today. From the

At one point in the battle for Tanga (November 7-8, 1914), a British landing force and their Sepoy allies were routed and driven back to the sea by millions of

At one point in the battle for Tanga (November 7-8, 1914), a British landing force and their Sepoy allies were routed and driven back to the sea by millions of

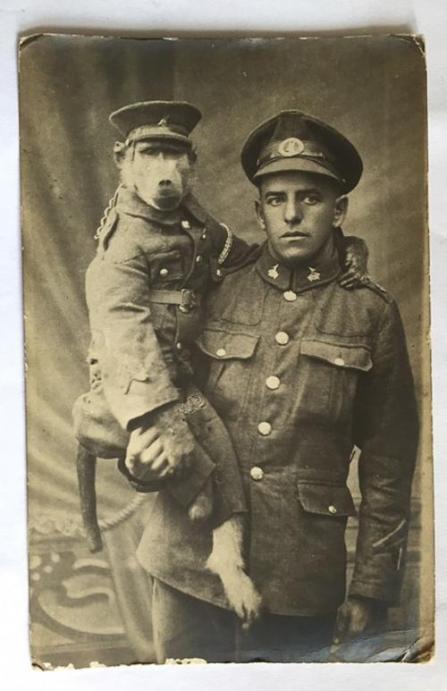

In 1964, the year Lettow-Vorbeck died, the Bundestag voted to give back pay to former African warriors who had fought with German forces in WWI. Some 350 elderly Ascaris showed up. A few could produce certificates given them back in 1918, some had scraps of old uniforms. Precious few could prove their former service to the German Empire.

In 1964, the year Lettow-Vorbeck died, the Bundestag voted to give back pay to former African warriors who had fought with German forces in WWI. Some 350 elderly Ascaris showed up. A few could produce certificates given them back in 1918, some had scraps of old uniforms. Precious few could prove their former service to the German Empire. A Trivial Matter

A Trivial Matter

By the 80s, market analysts believed that baby boomers were likely to switch to diet drinks as they aged, and any growth in the full calorie segment was going to come from younger consumers who preferred the sweeter taste of Pepsi.

By the 80s, market analysts believed that baby boomers were likely to switch to diet drinks as they aged, and any growth in the full calorie segment was going to come from younger consumers who preferred the sweeter taste of Pepsi.

Even Max Headroom and his “C-c-c-catch the wave!” couldn’t save the company.

Even Max Headroom and his “C-c-c-catch the wave!” couldn’t save the company.

You must be logged in to post a comment.