For the Islamic world, the 11th century was a time of political instability. The Fatimid Caliphate, established in 909 and headquartered in Cairo, found itself in sharp decline by the year 1090.

Within 100 years, the Fatimids would disappear altogether, eclipsed by the Abbasid Caliphate of An-Nasir Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, better known to anyone familiar with the story of Richard Lionheart, as Saladin.

To the east lay the Great Seljuk Empire, the Turko-Persian, Sunni Muslim state established in 1037 and stretching from the former Sassanid domains of modern-day Iran and Iraq, to the Hindu Kush. An “appanage” or “family federation” state, the Seljuk empire was itself in flux after a series of succession contests and destined to disappear in 1194.

Into the gap there arose the “Old Man of the Mountain”, Hassan-i Sabbah, and a fanatically loyal, secret sect of Nizari Ismaili followers, called Assassins.

The name derives from the Arabic “Hashashin”, meaning “those faithful to the foundation”. Marco Polo related a tale that the old man got such fervent loyalty from his young followers by drugging and leading them to a “paradise” of earthly delights, to which only he could bring them back. The story is most likely apocryphal. There is little evidence that hashish was ever used by the sect.

More likely that Sabbah’s followers believed him to be divine, personally selected by Allah. The man didn’t need to drug his “Fida’i” (self-sacrificing agents), he was infallible. His every whim would be obeyed as the literal Word of God.

The mountain fortification of Alamut in northern Persia was all but impervious to defeat by military means, but not to the two-years long campaign of stealth and pretend friendship practiced by Sabbah and his followers. Alamut fell in a virtually bloodless takeover in 1090, becoming the headquarters of the Nizari Ismaili state.

Why Sabbah would have founded such an order is unclear, if not in pursuit of his own personal and political goals. By the time of the first Crusade (1095-1099) the Nizari Isma’ili leader found himself pitted against Muslim and Christian rivals, alike.

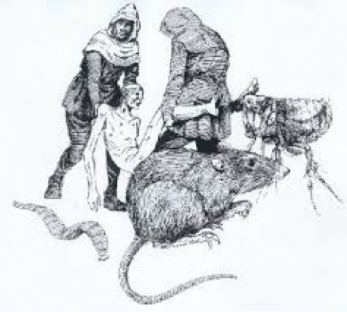

Western, Arabic, Syriac and Persian sources alike depicted the Assassins as trained killers, equally adept with dagger, arrow and poison alike.

Sabbah would order the elimination of his rivals, often up close. From religious figures to politicians and generals, assassinations were preferably carried out in broad daylight, lest everyone absorb the intended message.

The assassin could carry out the hit or insert himself and wait for years, for the opportunity to strike. Either way, he fully expected to die in carrying out his charge, a fact which troubled him not at all, knowing that he would awake, in paradise.

While the “Fida’in” occupied the lowest rank of the order, great care was devoted to their education and training. Possessed of all the physical prowess of youth, the individual assassin was intelligent and well-read, highly trained in combat tactics, the art of disguise and the skills of the expert horseman. All the necessary traits for anyone who would penetrate enemy territory, insinuate himself into their ranks, and murder the victim who had learned to trust him.

Sometimes, a credible threat of assassination was as effective as murder itself. When the new Seljuk Sultan Ahmad Sanjar rebuffed Hashashin diplomatic overtures in 1097, the sultan awoke one morning to find a dagger struck fast in the ground, next to his bed. A messenger arrived sometime later from the old man of the mountain. “Did I not wish the sultan well” he asked, “that the dagger which was struck in the hard ground would have been planted on your soft breast?” The technique worked nicely. For the rest of his days, Sanjar was happy to allow the Hashashin to collect tolls from travelers. The Sultan even provided them with a pension, collected from the inhabitants of the lands they occupied.

The great Saladin himself awoke one morning, to find a note resting on his chest, along with a poisoned cake. The message was clear. Sultan of all Egypt and Syria though he was, Saladin made an alliance with the rebel sect. There were no more attempts on his life.

Over the course of 200 years, the assassins occupied scores of mountain redoubts, while Alamut remained its principle quarters.

It’s impossible to know how many of the hundreds of political assassinations of this period were attributable to the followers of Hassan-i Sabbah. Without a doubt, their fearsome reputation ascribed more political murder to the sect than it was actually responsible for.

The Fida’in of Hassan-i Sabbah were some of the most feared killers of the middle ages. Scary as they were, there came a time when the order of the assassins tangled with someone far scarier than themselves.

In 1250, the grand master dispatched his killers to Karakorum in order to murder the Great Khan of the “Golden Horde” and great grandson of Genghis Kahn himself, Möngke. That turned out to be a bad idea.

The Nestorian Christian ally of the Mongol Empire Kitbuqa Noyan, was ordered to destroy several Hashashin fortresses in 1253. In 1255. Möngke’s brother Hulagu rode out at the head of the largest Mongol army ever assembled and no fewer than 1,000 Chinese engineer squads. Their orders were to treat those who submitted with kindness, and to utterly destroy those who did not.

That he did. Rukn al-Dīn Khurshāh, fifth and final Imam who ruled at Alamut, submitted after four days of preliminary bombardment. On December 15, 1256, Mongol forces under the command of Hulagu Khan entered the Hashshashin stronghold at Alamut Castle.

Alamut was destroyed, the defeated hashashin leader paraded before subordinate fortresses, each of which was destroyed in its turn.

Some Hashashin continued to exist in small, fractured groups, though their power was at an end. Destroyed by the power of the Mongol horde, 767 years ago today.

Charles consolidated his power in a series of wars between 718 and 732, subjugating Bavarians Allemanii, and pagan Saxons, and combining the formerly separate Kingdoms of Nuestria in the northwest of modern day France with that of Austrasia in the east.

Charles consolidated his power in a series of wars between 718 and 732, subjugating Bavarians Allemanii, and pagan Saxons, and combining the formerly separate Kingdoms of Nuestria in the northwest of modern day France with that of Austrasia in the east.

You must be logged in to post a comment.