From the 7th century BC, the Roman calendar attempted to follow the cycles of the moon. The method frequently fell out of phase with the change of seasons, requiring the random addition of days. The Pontifices, the Roman body charged with overseeing the calendar, made matters worse. They were known to add days to extend political terms, and to interfere with elections. Military campaigns were won or lost due to confusion over dates. By the time of Julius Caesar, things needed to change.

Caesar hired the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes to help straighten things out. The astronomer calculated that a proper year was 365¼ days, which more accurately tracked the solar, and not the lunar year. “Do like the Egyptians”, he might have said, the new “Julian” calendar went into effect in 46BC. Caesar decreed that 67 days be added that year, moving the New Year’s start from March to January 1. The first new year of the new calendar was January 1, 45BC.

Caesar synchronized his calendar with the sun by adding a day to every February, and changed the name of the seventh month from Quintilis to Julius, to honor himself. Rank hath its privileges.

Not to be outdone, Caesar’s successor changed the 8th month from Sextilis to Augustus. 2,062 years later, we still have July and August.

Sosigenes was close with his 365¼ day long year, but not quite there. The correct value of a solar year is 365.242199 days. By the year 1000, that 11-minute error had added seven days. To fix the problem, Pope Gregory XIII commissioned Jesuit astronomer Christopher Clavius to come up with yet another calendar. The Gregorian calendar was implemented in 1582, omitting ten days and adding a day on every fourth February.

Sosigenes was close with his 365¼ day long year, but not quite there. The correct value of a solar year is 365.242199 days. By the year 1000, that 11-minute error had added seven days. To fix the problem, Pope Gregory XIII commissioned Jesuit astronomer Christopher Clavius to come up with yet another calendar. The Gregorian calendar was implemented in 1582, omitting ten days and adding a day on every fourth February.

Most of the non-Catholic world took 170 years to adopt the Gregorian calendar. Britain and its American colonies “lost” 11 days synchronizing with it in 1752. The last holdout, Greece, would formally adopt the Gregorian calendar in 1923. Since then, we’ve all gathered to celebrate New Year’s Day on the 1st of January.

For years, New Years’ eve celebrations were held at Trinity Church, where revelers would gather to “ring in the new”. The New York Times newspaper moved into “Longacre Square” just after the turn of the 20th century. Times owner Adolph Ochs held his first fireworks celebration on December 31, 1903, with almost 200,000 people attending the event. Four years later, Ochs wanted a bigger spectacle to draw attention to the newly renamed Times Square. He asked the newspaper’s chief electrician, Walter Painer, for an idea. Painer suggested a time ball.

A time ball is a marine time signaling device, a large painted ball which is dropped at a predetermined rate, enabling mariners to synchronize shipboard marine chronometers for purposes of navigation. The first one was built in 1829 in Portsmouth, England, by Robert Wauchope, a Captain in the Royal Navy.

Time balls were obsolete technology by the 20th century, but it fit the Times’ purposes, nicely. A young immigrant metalworker named Jacob Starr designed a 5′ wide, 700-lb iron and wooden ball, decorated with 100 25-watt incandescent bulbs. For most of the twentieth century the company he founded, sign maker Artkraft Strauss, was responsible for lowering the ball.

That first ball was hoist up a flagpole by five men on December 31, 1907. Once it hit the roof of the building, the ball completed an electric circuit, lighting up a sign and touching off a fireworks display.

That first ball was hoist up a flagpole by five men on December 31, 1907. Once it hit the roof of the building, the ball completed an electric circuit, lighting up a sign and touching off a fireworks display.

The newspaper no longer occupies the building at 1 Times Square, but the tradition continues. One of seven versions of the Times Square ball has marked the coming of the new year ever since, with the exceptions of 1942 and ’43, due to the wartime need to dim out the lights.

The version used the last few years is 12′ wide, weighing in at 11,875lbs; a great sphere of 2,688 Waterford Crystal triangles, illuminated by 32,256 Philips LED bulbs and producing more than 16 million colors. It used to be that the ball only came out for New Year. The last few years, you can see the thing, any time you like.

In most English-speaking countries, the singing of “Auld Lang Syne”, is the traditional end to the New Year’s celebration. Written by the Scottish poet Robert Burns in 1788, the tune comes from an old pentatonic Scots folk melody. The original verse, phonetically spelled as a Scots-speaker would pronounce it, sounds like this:

“Shid ald akwentans bee firgot, an nivir brocht ti mynd?

Shid ald akwentans bee firgot, an ald lang syn?”

CHORUS

“Fir ald lang syn, ma jo, fir ald lang syn,

wil tak a cup o kyndnes yet, fir ald lang syn.

An sheerly yil bee yur pynt-staup! an sheerly al bee myn!

An will tak a cup o kyndnes yet, fir ald lang syn”.

CHORUS

“We twa hay rin aboot the braes, an pood the gowans fyn;

Bit weev wandert monae a weery fet, sin ald lang syn”.

CHORUS

“We twa hay pedilt in the burn, fray mornin sun til dyn;

But seas between us bred hay roard sin ald lang syn”.

CHORUS

“An thers a han, my trustee feer! an gees a han o thyn!

And we’ll tak a richt gude-willie-waucht, fir ald lang syn”.

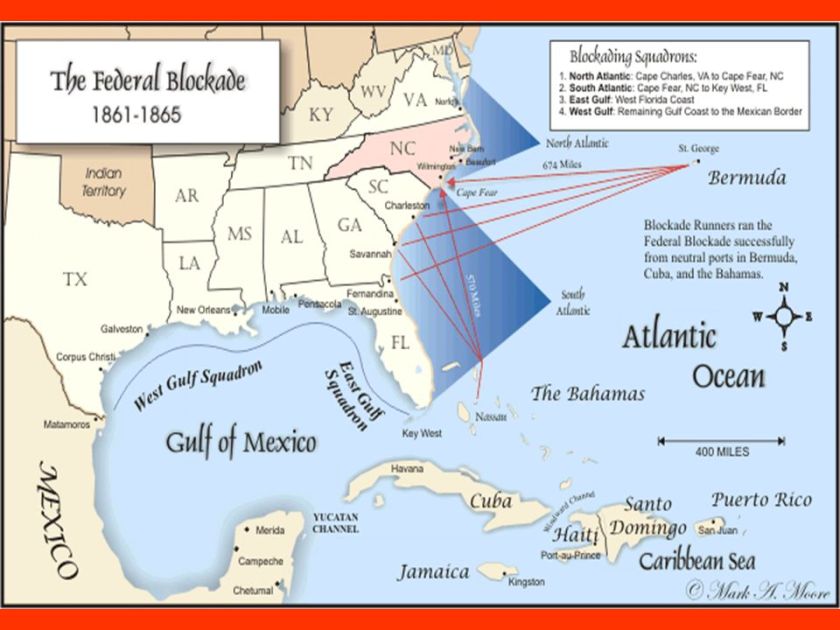

President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation soon after taking office, threatening to blockade southern coastlines. It wasn’t long before the “Anaconda Plan” went into effect, a naval blockade extending 3,500 miles along the Atlantic coastline and Gulf of Mexico, up into the lower Mississippi River.

President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation soon after taking office, threatening to blockade southern coastlines. It wasn’t long before the “Anaconda Plan” went into effect, a naval blockade extending 3,500 miles along the Atlantic coastline and Gulf of Mexico, up into the lower Mississippi River. Cotton would ship out of Mobile, Charleston, Wilmington and other ports, while weapons and other manufactured goods would come back in. Sometimes, these goods would make the whole trans-Atlantic voyage. Often, they would stop at neutral ports in Cuba or the Bahamas.

Cotton would ship out of Mobile, Charleston, Wilmington and other ports, while weapons and other manufactured goods would come back in. Sometimes, these goods would make the whole trans-Atlantic voyage. Often, they would stop at neutral ports in Cuba or the Bahamas.

Forty years later and half a world away, what would one day become South Africa was divided into four entities: the two British possessions of Cape Colony and Natal, and the two Boer (Dutch) Republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic, better known as Transvaal. Of the four states, Natal and the two Boer Republics were mainly agricultural, populated by subsistence farmers. The Cape Colony was by far the largest, dominating the other three economically, culturally, and socially.

Forty years later and half a world away, what would one day become South Africa was divided into four entities: the two British possessions of Cape Colony and Natal, and the two Boer (Dutch) Republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic, better known as Transvaal. Of the four states, Natal and the two Boer Republics were mainly agricultural, populated by subsistence farmers. The Cape Colony was by far the largest, dominating the other three economically, culturally, and socially.

Sixteen countries sent troops to South Korea’s aid, about 90% of whom were Americans. The Soviets sent material aid to the North, while Communist China sent troops. The Korean War lasted three years, causing the death or disappearance of over 2,000,000 on all sides, combining military and civilian.

Sixteen countries sent troops to South Korea’s aid, about 90% of whom were Americans. The Soviets sent material aid to the North, while Communist China sent troops. The Korean War lasted three years, causing the death or disappearance of over 2,000,000 on all sides, combining military and civilian. The night-time satellite image of the two Koreas, tells the story of what happened next. In the south, the Republic of Korea (ROK) developed into a successful constitutional Republic, a G-20 nation with an economy ranking 11th in the world in nominal GDP, and 13th in terms of purchasing power parity.

The night-time satellite image of the two Koreas, tells the story of what happened next. In the south, the Republic of Korea (ROK) developed into a successful constitutional Republic, a G-20 nation with an economy ranking 11th in the world in nominal GDP, and 13th in terms of purchasing power parity. Son of the founder of the Juche Ideal, Kim Jung Il, was an enthusiastic film buff. In a move that would make Caligula blush, Kim had South Korean film maker Shin Sang Ok kidnapped along with his actress ex-wife, Choi Eun Hee. After four years spent starving in a North Korean gulag, the couple accepted Kim’s “suggestion” to re-marry and go to work for him, producing the less-than-box-office-smash “Pulgasari”, a kind of North Korean Godzilla film.

Son of the founder of the Juche Ideal, Kim Jung Il, was an enthusiastic film buff. In a move that would make Caligula blush, Kim had South Korean film maker Shin Sang Ok kidnapped along with his actress ex-wife, Choi Eun Hee. After four years spent starving in a North Korean gulag, the couple accepted Kim’s “suggestion” to re-marry and go to work for him, producing the less-than-box-office-smash “Pulgasari”, a kind of North Korean Godzilla film.

A few tried to replicate the event the following year, but there were explicit orders preventing it. Captain Llewelyn Wyn Griffith recorded that after a night of exchanging carols, dawn on Christmas Day 1915 saw a “rush of men from both sides … [and] a feverish exchange of souvenirs” before the men were quickly called back by their officers.

A few tried to replicate the event the following year, but there were explicit orders preventing it. Captain Llewelyn Wyn Griffith recorded that after a night of exchanging carols, dawn on Christmas Day 1915 saw a “rush of men from both sides … [and] a feverish exchange of souvenirs” before the men were quickly called back by their officers. German soldier Richard Schirrmann wrote in December 1915, “When the Christmas bells sounded in the villages of the Vosges behind the lines …. something fantastically unmilitary occurred. German and French troops spontaneously made peace and ceased hostilities; they visited each other through disused trench tunnels, and exchanged wine, cognac and cigarettes for Westphalian black bread, biscuits and ham. This suited them so well that they remained good friends even after Christmas was over”.

German soldier Richard Schirrmann wrote in December 1915, “When the Christmas bells sounded in the villages of the Vosges behind the lines …. something fantastically unmilitary occurred. German and French troops spontaneously made peace and ceased hostilities; they visited each other through disused trench tunnels, and exchanged wine, cognac and cigarettes for Westphalian black bread, biscuits and ham. This suited them so well that they remained good friends even after Christmas was over”. Even so, there is evidence of a small Christmas truce occurring in 1916, previously unknown to historians. 23-year-old Private Ronald MacKinnon of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, wrote home about German and Canadian soldiers reaching across battle lines near Arras, sharing Christmas greetings and trading gifts. “I had quite a good Christmas considering I was in the front line”, he wrote. “Christmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Christmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars”. The letter ends with Private MacKinnon noting that “Christmas was ‘tray bon’, which means very good.”

Even so, there is evidence of a small Christmas truce occurring in 1916, previously unknown to historians. 23-year-old Private Ronald MacKinnon of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, wrote home about German and Canadian soldiers reaching across battle lines near Arras, sharing Christmas greetings and trading gifts. “I had quite a good Christmas considering I was in the front line”, he wrote. “Christmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Christmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars”. The letter ends with Private MacKinnon noting that “Christmas was ‘tray bon’, which means very good.”

The American public was outraged and there were calls for war in 1807, when HMS Leopard overtook the USS Chesapeake, kidnapping three American-born sailors and one British deserter, leaving another three dead and 18 wounded.

The American public was outraged and there were calls for war in 1807, when HMS Leopard overtook the USS Chesapeake, kidnapping three American-born sailors and one British deserter, leaving another three dead and 18 wounded. Outside of the British Royal Navy, the practice of kidnapping people to serve as shipboard labor was known as “crimping”. Low wages combined with the gold rushes of the 19th century left the waterfront painfully short of manpower, skilled and unskilled, alike. “Boarding Masters” had the job of putting together ship’s crews, and were paid for each recruit. There was strong incentive to produce as many able bodies, as possible. Unwilling men were “shanghaied” by means of trickery, intimidation or violence, most often rendered unconscious and delivered to waiting ships, for a fee.

Outside of the British Royal Navy, the practice of kidnapping people to serve as shipboard labor was known as “crimping”. Low wages combined with the gold rushes of the 19th century left the waterfront painfully short of manpower, skilled and unskilled, alike. “Boarding Masters” had the job of putting together ship’s crews, and were paid for each recruit. There was strong incentive to produce as many able bodies, as possible. Unwilling men were “shanghaied” by means of trickery, intimidation or violence, most often rendered unconscious and delivered to waiting ships, for a fee.

San Francisco political bosses William T. Higgins, (R) and Chris “Blind Boss” Buckley (D) were both notable crimps, and well positioned to look after their political interests. Notorious crimps such as Joseph “Frenchy” Franklin and George Lewis were elected to the California state legislature. There was no better spot, from which to ensure that no legislation would interfere with such a lucrative trade.

San Francisco political bosses William T. Higgins, (R) and Chris “Blind Boss” Buckley (D) were both notable crimps, and well positioned to look after their political interests. Notorious crimps such as Joseph “Frenchy” Franklin and George Lewis were elected to the California state legislature. There was no better spot, from which to ensure that no legislation would interfere with such a lucrative trade. Imagine the hangover the next morning, to wake up and find you’re now at sea, bound for somewhere in the far east. Regulars knew about the trap door and avoided it at all costs, knowing that anyone going over there, was “fair game”.

Imagine the hangover the next morning, to wake up and find you’re now at sea, bound for somewhere in the far east. Regulars knew about the trap door and avoided it at all costs, knowing that anyone going over there, was “fair game”.

Stranded and alone in the high Andes, meager supplies soon gave out. A few chocolate bars, assorted snacks and several bottles of wine. It was gone within days, as the survivors scoured the wreckage for crumbs. They ate leather from suitcases, tore apart seats hoping to find straw, finding nothing but inedible foam. Nothing grew at this altitude. There were no animals. There was nothing in that desolate place but metal, glass, ice and rock. And the frozen bodies of the dead.

Stranded and alone in the high Andes, meager supplies soon gave out. A few chocolate bars, assorted snacks and several bottles of wine. It was gone within days, as the survivors scoured the wreckage for crumbs. They ate leather from suitcases, tore apart seats hoping to find straw, finding nothing but inedible foam. Nothing grew at this altitude. There were no animals. There was nothing in that desolate place but metal, glass, ice and rock. And the frozen bodies of the dead.

The Juan Valdez of the coffee commercials is an “Arriero”, a man who transports goods using pack animals. Parrado and Canessa had hiked for almost two weeks when they were building a fire by a river, and spotted such a man on the other side. Sergio Catalán probably didn’t believe his eyes at first, but he shouted across the river. “Tomorrow”.

The Juan Valdez of the coffee commercials is an “Arriero”, a man who transports goods using pack animals. Parrado and Canessa had hiked for almost two weeks when they were building a fire by a river, and spotted such a man on the other side. Sergio Catalán probably didn’t believe his eyes at first, but he shouted across the river. “Tomorrow”.

Augusta Marie Chiwy (“Shee-wee”) was the bi-racial daughter of a Belgian veterinarian and a Congolese mother, she never knew.

Augusta Marie Chiwy (“Shee-wee”) was the bi-racial daughter of a Belgian veterinarian and a Congolese mother, she never knew. Chiwy married after the war, and rarely talked about her experience in Bastogne. It took King a full 18 months to coax the story out of her. The result was the 2015 Emmy award winning historical documentary, “Searching for Augusta, The Forgotten Angel of Bastogne”.

Chiwy married after the war, and rarely talked about her experience in Bastogne. It took King a full 18 months to coax the story out of her. The result was the 2015 Emmy award winning historical documentary, “Searching for Augusta, The Forgotten Angel of Bastogne”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.