During the early colonial period, American newspapers were little more than “wretched little” sheets according to America’s “1st newsboy”, Benjamin Franklin. Scarcely more than sidelines to keep the presses occupied.

Newspapers were distributed by mail in the early years, thanks to generous subsidies from the Postal Act of 1792. In 1800, the United States could boast somewhere between 150 – 200 newspapers. Thirty-five years later, some 1,200 were competing for readership.

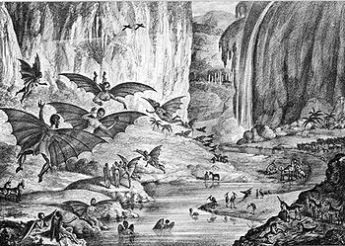

We hear a lot these days about “fake news”, but that’s nothing new. In 1835, the New York Sun published a six-part series describing civilization, on the moon. The “Great Moon Hoax”, ostensibly reprinted from the Edinburgh Courant, was falsely attributed to the work of Sir John Herschel, one of the best known astronomers of the age.

Whatever it took, to sell newspapers.

Two years earlier, Sun publisher Benjamin Day ran a Help-Wanted advertisement, looking for adults to help expand circulation. “To the unemployed — A number of steady men can find employment by vending this paper. A liberal discount is allowed to those who buy and sell again“. To Day’s surprise, his ad didn’t produce adult applicants as expected. Instead, the notice attracted children.

Today, kids make up a minimal part of the American workforce, but that wasn’t always so. Child labor played an integral part in the agricultural and handicraft economy, working on family farms or hiring out to other farmers. Boys customarily apprenticed to the trades by ages 10 – 14. As late as 1900, fully 18% of the American workforce was under the age of sixteen.

Benjamin Day’s first newspaper “hawker” was Bernard Flaherty, a ten-year-old Irish immigrant. The kid was good at it too, crying out lurid headlines, to passers-by: “Double Distilled Villainy!” “Cursed Effects of Drunkenness!” “Awful Occurrence!” “Infamous Affair!” “Extra! Extra! Read all about it!”

Hordes of street urchins swarmed the tenements and alleyways of American cities. During the 1870s, homeless children were estimated at 20,000 – 30,000 in New York alone, as much as 12% of school-age children in the city.

For thousands of them newspapers were all that stood in the way, of an empty belly.

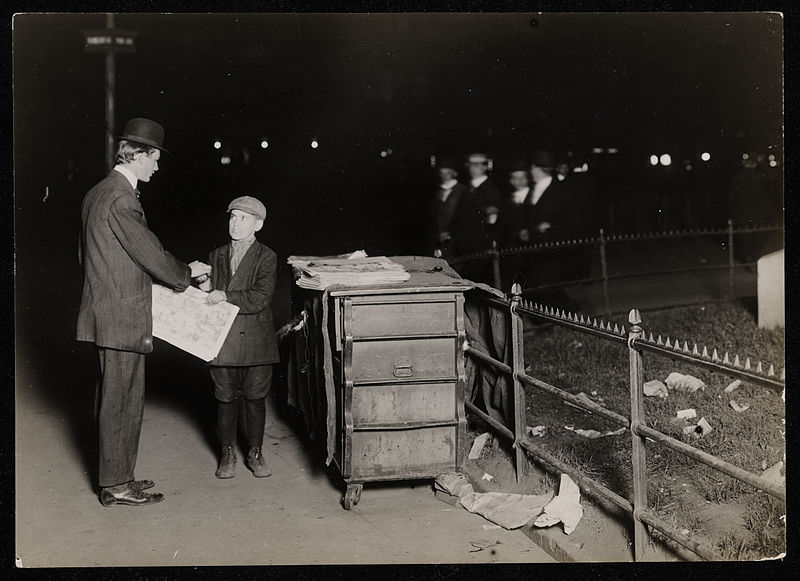

Adults had no interest in the minuscule income, and left the newsboys (and girls) to their own devices. “Newsies” bought papers at discounted prices and peddled them on the street. Others worked saloons and houses of prostitution. They weren’t allowed to return any left unsold, and worked well into the night to sell every paper.

For that, newsies earned about 30¢ a day. Enough for a bite to eat, to afford enough papers to do it again the following day, and maybe a 5¢ bed in the newsboy’s home.

Competition was ferocious among hundreds of papers, and business practices were lamentable. In 1886, the Brooklyn Times tried a new idea. The city was expanding rapidly, swallowing up previously independent townships along the Long Island shore. The Times charged Western District newsboys a penny a paper, while Eastern District kids paid 1 1/5¢.

The plan was expected to “push sales vigorously in new directions.” It took about a hot minute for newsies to get wise, and hundreds of them descended on the Times’ offices with sticks and rocks. On March 29, several police officers and a driver’s bullwhip were needed to get the wagons out of the South 8th Street distribution offices. One of the trucks was overturned, later that day.

That time, the newsboy strike lasted a couple of days, enforced by roving gangs of street kids and “backed by a number of roughs”. In the end, the Times agreed to lower its price to a penny apiece, in all districts. Other such strikes would not be ended so quickly, or so easily.

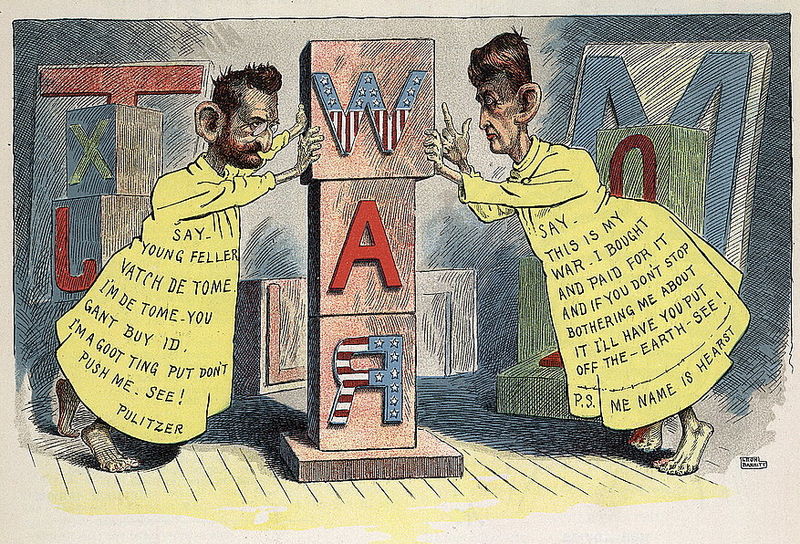

In those days, the Caribbean island of Cuba was ruled from Spain. After decades spent in the struggle for independence, many saw parallels between the “Cuba Libre” movement, and America’s own Revolution of the previous century. In 1897-’98, few wanted war with Spain over Cuban interests more than Assistant Naval Secretary Theodore Roosevelt, and New York publishers Joseph Pulitzer & William Randolph Hearst.

This was the height of the Yellow Journalism period, and newspapers clamored for war. Hearst illustrator Frederic Remington was sent to Cuba, to document “atrocities”. On finding none, Remington wired: “There will be no war. I wish to return”. Hearst wired back: “Please remain. You furnish the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war.” President McKinley urged calm, but agreed to send the armored cruiser USS Maine, to protect US “interests”.

The explosion that sank the Maine on February 15 killing 268 Americans was almost certainly accidental, but that wouldn’t be known for decades. Events quickly spun out of control and, on April 21, 1898, the US blockaded the Caribbean island. Spain gave notice two days later, that it would declare war if US forces invaded its territory. Congress declared on April 25 that a state of war had existed between Spain and the United States, since the 21st.

Several days later, newsboys were shouting the headline: “How do you like the Journal’s war?”

The Spanish-American War was over in 3 months, 3 weeks and 2 days, but circulation was great while it lasted. Publishers cashed in, raising the cost of newsboy bundles from 50¢ to 60¢ – the increase temporarily offset by higher sales. Publishers reverted to 50¢ per 100 after the war, with the notable exceptions of Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, and William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal.

Newsies struck the two in 1899, refusing to sell their papers. 5,000 newsboys blocked the Brooklyn Bridge, bringing traffic to a standstill. Competing papers such as the New York Tribune couldn’t get enough of the likes of strike “President” Dave Simmons, the boy “prize-fighter”, Barney “Peanuts”, “Crutch” Morris, and others. The charismatic, one-eyed strike leader “Kid Blink”, was a favorite: “Friens and feller workers. This is a time which tries de hearts of men. Dis is de time when we’se got to stick together like glue…. We know wot we wants and we’ll git it even if we is blind”.

Neither Hearst nor Pulitzer ever dropped their price, but they did agree to take back unsold papers.

Long before modern notions of child welfare, street kids had precious few to look out for them, beyond themselves. “Dutch” Johnson, Brooklyn’s “Racetrack Newsie”, caught cold, in 1905. The illness soon turned more serious, and he was found unconscious on a pile of catalogs. Brought to Bellevue Hospital by the East River, the 16-year-old was informed that it was pneumonia. This was before the age of antibiotics. There was no chance.

“It goes”, Dutch said, in a voice barely audible. “Only I ain’t got no money and I’d like to be put away decent”.

Bookmaker “Con” Shannon offered to take up a collection for the burial. He could have easily produced hundreds from bookies and gamblers. Dutch’s diminutive successor “Boston”, spoke up. “Naw”, he said “we’re on de job and nobody else”. So it was that “Gimpy”, “Dusty”, and the other urchins of Sheepshead Bay pitched in with their pennies, their nickels and their dimes. For $53.40, Dutch Johnson would have his plot in Linden Hill Cemetery, complete with small stone marker. Not a plain black wagon and a nameless grave in some anonymous Potter’s Field.

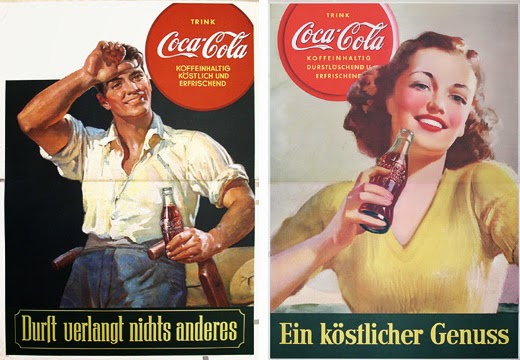

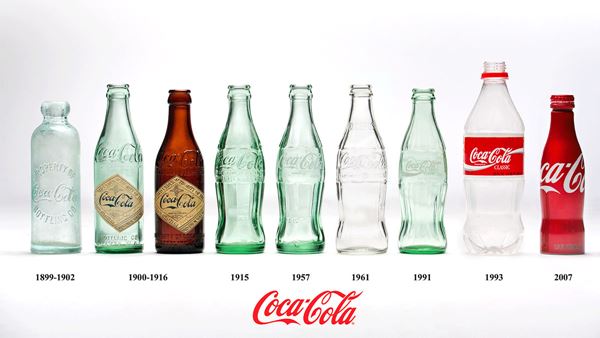

At first sold for their therapeutic value, consumers increasingly bought carbonated beverages for refreshment.

At first sold for their therapeutic value, consumers increasingly bought carbonated beverages for refreshment. The most famous rivalry in the soft drink business began in the 1930s, when Pepsi offered a 12oz bottle for the same 5¢ as Coca Cola’s six ounces.

The most famous rivalry in the soft drink business began in the 1930s, when Pepsi offered a 12oz bottle for the same 5¢ as Coca Cola’s six ounces. By the ’80s, market analysts believed that aging baby boomers were likely to switch to diet drinks and any growth in the full calorie segment was going to come from younger consumers, who preferred the sweeter taste of Pepsi.

By the ’80s, market analysts believed that aging baby boomers were likely to switch to diet drinks and any growth in the full calorie segment was going to come from younger consumers, who preferred the sweeter taste of Pepsi. On an April Friday in 1985, Coke let the media know that a major announcement was coming the following Tuesday. Coca Cola officials spent a busy weekend preparing for the re-launch, while Pepsi Executives announced a company-wide holiday, taking out a full page ad in the New York Times, crowing that “Pepsi had Won the Cola Wars”.

On an April Friday in 1985, Coke let the media know that a major announcement was coming the following Tuesday. Coca Cola officials spent a busy weekend preparing for the re-launch, while Pepsi Executives announced a company-wide holiday, taking out a full page ad in the New York Times, crowing that “Pepsi had Won the Cola Wars”.

Not even Max Headroom and his stuttering “C-c-c-catch the wave!” could save the company.

Not even Max Headroom and his stuttering “C-c-c-catch the wave!” could save the company. So it was that, in 1985, Coca Cola announced they’d bring back the 91-year old formula. One reporter asked Keough if the whole thing had been a publicity stunt. Keough’s answer should be taught in business schools the world over, if it isn’t already. “We’re not that dumb,” he said, “and we’re not that smart”.

So it was that, in 1985, Coca Cola announced they’d bring back the 91-year old formula. One reporter asked Keough if the whole thing had been a publicity stunt. Keough’s answer should be taught in business schools the world over, if it isn’t already. “We’re not that dumb,” he said, “and we’re not that smart”.

By the 80s, market analysts believed that baby boomers were likely to switch to diet drinks as they aged, and any growth in the full calorie segment was going to come from younger consumers who preferred the sweeter taste of Pepsi.

By the 80s, market analysts believed that baby boomers were likely to switch to diet drinks as they aged, and any growth in the full calorie segment was going to come from younger consumers who preferred the sweeter taste of Pepsi.

Even Max Headroom and his “C-c-c-catch the wave!” couldn’t save the company.

Even Max Headroom and his “C-c-c-catch the wave!” couldn’t save the company.

NBC executives, were thrilled. The AFL was only eight years old in 1968 and as yet unproven compared with the older league, the NFL/AFL merger still two years in the future.

NBC executives, were thrilled. The AFL was only eight years old in 1968 and as yet unproven compared with the older league, the NFL/AFL merger still two years in the future.

The “Heidi Bowl” was prime time news the following night, on all three networks. NBC’s Huntley-Brinkley Report aired the last sixty seconds while ABC Evening News anchor Frank Reynolds read excerpts from the movie, with clips of the Raiders’ two touchdowns cut in. CBS Evening News’ Harry Reasoner announced the “result” of the game: “Heidi married the goat-herder“.

The “Heidi Bowl” was prime time news the following night, on all three networks. NBC’s Huntley-Brinkley Report aired the last sixty seconds while ABC Evening News anchor Frank Reynolds read excerpts from the movie, with clips of the Raiders’ two touchdowns cut in. CBS Evening News’ Harry Reasoner announced the “result” of the game: “Heidi married the goat-herder“.

You must be logged in to post a comment.