Only hours from now, families will gather from far and near, around the Christmas table. There will be moist and savory stuffing, and green bean casserole. Creamy mashed potatoes and orange cranberry sauce. And there, the centerpiece of the feast. Slow-roasted and steaming in that silver tray the golden brown, delicious, roast hippopotamus.

Wait…Uhh…What?

The World Cotton Centennial and World’s Fair of 1884 began its second week on December 23. Located in New Orleans, Louisiana that year, among its many wonders was the never-before seen Eichornia crassipes, a gift from the Japanese delegation. The Water Hyacinth.

Visitors marveled at this beautiful aquatic herb, with yellow spots accentuating the petals of delicate purple and blue flowers floating across tranquil ponds on a mat of thick, green leaves.

The seeds of Eichornia crassipes are spread by wind, flood, birds and humans and remain viable, for 30 years. Beautiful as it is to look at, the Water Hyacinth is an “alpha plant”, an aquatic equivalent to the Japanese invasive perennial Kudzu, the “vine that ate the south”. Impenetrable floating mats choke out native habitats and species while thick roots impede the passage of vessels, large and small. The stuff is toxic if ingested by humans and most animals and costs a fortune, to remove.

This plant native from the Amazon basin quickly broke the bounds of the 1884 World’s Fair, spreading across the bayous and waterways of Louisiana, and beyond.

During the first decade of the 20th century, an exploding American population could barely keep up with its own need for food. Especially, meat. The problem reached crisis proportions in 1910, with over grazing and a severe cattle shortage. Americans were seriously discussing the idea of eating dogs.

Enter Louisiana member of the House of Representatives, New Iberia’s own Robert Foligny Broussard, with a solution to both problems. Lake Bacon.

The attorney from Louisiana’s 3rd Congressional district proposed H.R. 23621 in 1910, otherwise known as the “American Hippo” bill. Broussard’s proposed legislation enjoyed enthusiastic support from Theodore Roosevelt and the New York Times, alike. One Agricultural official estimated that a free-range hippo herd could produce up to a million tons of meat, every year.

Lippincott’s monthly magazine waxed rhapsodic: “This animal, homely as a steamroller, is the embodiment of salvation. Peace, plenty and contentment lie before us, and a new life with new experiences, new opportunities, new vigour, new romance, folded in that golden future, when the meadows and the bayous of our southern lands shall swarm with herds of hippopotami”.

With a name deriving from the Greek term “River Horse”, the common hippopotamus is the third largest land animal living today. Despite a physical resemblance to hogs and other even-toed ungulates, Hippopotamidae’s closest living relatives are cetaceans such as whales, dolphins and porpoises.

All well and good. The problem is, those things are dangerous.

The adult bull hippopotamus is skittish, extremely aggressive, unpredictable and highly territorial. Heaven help anyone caught between a cow and her young. Hippos can gallop at short sprints of 19 mph, only a little less than the top speed of Jamaican Sprinter Usain Bolt, and he’s “the fastest man who ever lived”.

To keyword search the “10 most dangerous animals in Africa” is to be rewarded with the knowledge that hippos are #1, responsible for more human fatalities than any other large animal in Africa.

Be that at it as it may, the animal is a voracious herbivore, spending daylight hours at the bottom of rivers & lakes, happily munching on vegetation.

Back to Broussard’s bill, what could be better than taking care of two problems at once? Otherwise unproductive swamps and bayous from Florida to East Texas would become home to great hordes of free-range hippos. The meat crisis would be averted. America would become a nation of hippo ranchers.

As Broussard’s bill wended its way through Congress, the measure picked up steam with the enthusiastic support of two men, mortal enemies who’d spent ten years in the African bush trying to kill each other. No, really.

Frederick Russell Burnham argued for four years for the introduction of African wildlife into the American food stream. A freelance scout and American adventurer, Burnham was known for his service to the British South Africa company, and to the British army in colonial Africa. The “King of Scouts’, commanding officers described Burnham as “half jackrabbit and half wolf”. A “man totally without fear.” One writer described Burnham’s life as “an endless chain of impossible achievements”, another “a man whose senses and abilities approached that of a wild predator”. He was the inspiration for the Indiana Jones character and for the Boy Scouts. Forget the Dos Equis guy. Frederick Burnham really was the real-life “most interesting man in the world“.

Fritz Duquesne? Well that’s another story. Frederick “Fritz” Joubert Duquesne was a Boer of French Huguenot ancestry, descended from Dutch settlers to South Africa. A smooth talking guerrilla fighter, the self-styled “Black Panther” once described himself as every bit the wild African animal, as any creature of the veld. An incandescent tower of hate for all things British, Duquesne was a liar, a chameleon, a man of 1,000 aliases who once spent seven months feigning paralysis, just so he could fool his jailers long enough to cut through his prison bars.

Destined to become a German spy it is he who lends his name to the infamous Duquesne Spy Ring, of World War 2.

Frederick Burnham described Duquesne, his mortal adversary: “He was one of the craftiest men I ever met. He had something of a genius of the Apache for avoiding a combat except in his own terms; yet he would be the last man I should choose to meet in a dark room for a finish fight armed only with knives“.

During the 2nd Boer war, these two men had sworn to kill each other. Now in 1910 the pair became partners in a mission to bring hippopotamus, to the American dinner table.

Biologically, there is little reason to believe that Hippo ranching wouldn’t work along the Gulf coast. Decades ago, Colombian drug kingpin Pablo Escobar introduced four hippos to the Columbian interior. Today, officials estimate that, within a few years, the hippo descendants of Escobar’s exotic animal menagerie will number 100 or more individuals.

Back to the American Hippo bill. Broussard’s measure went down to defeat by a single vote, but never entirely went away. Always the political calculator, Representative and later-Senator Broussard died with the bill on his legislative agenda, waiting for the right moment to reintroduce the thing.

Over time, the solution to the meat question became a matter of doubling down on what was already taking shape. Factory farms and confinement operations came to replace free ranges while the massive use of antibiotics replaced even the notion of balanced biological systems.

We may or may not have “traded up”. Today we contend with all manner of antibiotic-resistant “Superbugs”. The Louisiana department of wildlife and fisheries maintains no fewer than 85 separate aquatic vegetation control plans, aimed at the water hyacinth.

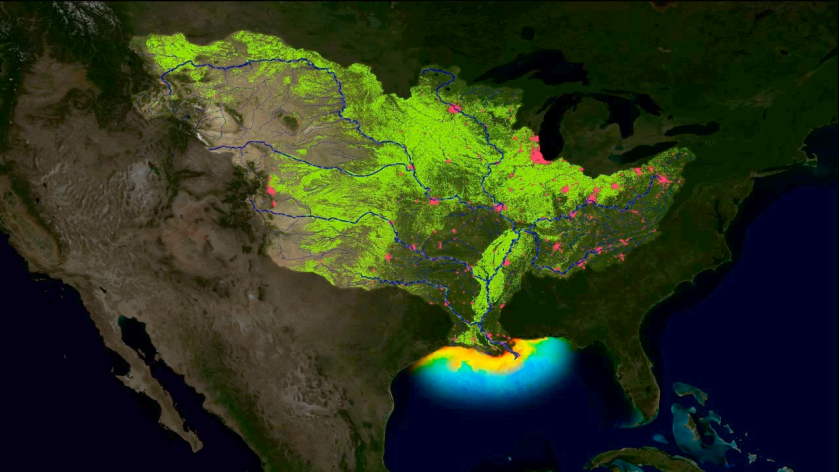

The effluent from factory farms from Montana to Pennsylvania works its way into the nation’s rivers and streams, washing out to the Mississippi Delta to a biological dead zone, the size of New Jersey.

As for that once golden future, Lippincott’s hippo herds roam only in the meadows and bayous of the imagination. Who knows, it may be for the best. I don’t know if we could’ve seen each other across the table, anyway. Not when that hippo came out of the oven.

You must be logged in to post a comment.