You’ve worked all your life. You’ve taken care of your family, paid your taxes, and paid your bills. You’ve even managed to put a few bucks aside, in hopes of a long and happy retirement. So…what if you never touched it and that “nest egg” was suddenly reduced by 10%…40%…70%.

The subject of currency devaluation is normally left to eggheads and academics. Hyperinflation is treated as an historical curiosity. But I wonder. Any economic textbook will tell you what fuels inflation. Even hyperinflation. What makes us think it couldn’t happen here?

Throughout antiquity, Roman law required that coinage retain a certain silver content. Precious metal made the coins themselves objects of value, and the Roman economy remained relatively stable for 500 years. Republic morphed into Empire over the 1st century BC, leading to a conga line of Emperors minting mountains of coins in their own likenesses. Slaves worked to death in Spanish silver mines. Birds fell from the sky over vast smelting fires, yet there was never enough silver. Silver content was inexorably reduced until the currency itself collapsed, in the 3rd century reign of Diocletian. A once powerful empire and its citizens were left to barter as best they could, in a world where currency had no value.

In the waning days of the Civil War, the Confederate dollar wasn’t worth the paper it was printed on. Paper money crashed in the post-Revolution Articles of Confederation period as well, when you could buy a sheep for two silver dollars, or 150 paper “Continental” dollars. Creditors literally hid from debtors, not wanting to be repaid in worthless paper currency. For generations after our founding, a thing could be described as worthless as, not worth a Continental.

The assistance of French King Louis XIV was invaluable to Revolutionary era Americans, but French state income was only about 357 million livres at the time, with expenses of over half a billion. France descended into its own Revolution, as the government printed “assignat”, notes purportedly backed by 4 billion livres in property expropriated form the church. 912 million livres were in circulation in 1791, rising to almost 46 billion in 1796. One historian described the economic policy of the Jacobins, the leftist radicals behind the Reign of Terror: “The attitude of the Jacobins about finances can be quite simply stated as an utter exhaustion of the present at the expense of the future”.

That sounds depressingly familiar.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was on the losing side of WW1, and was broken up after the war. Lacking the governmental structures of established states, the newly independent nation of Hungary began to experience inflation. Before the war, a US Dollar would have bought you 5 Kronen. by 1924 that number had risen, to 70,000.

Hungary replaced the Kronen with the Pengö in 1926, pegged to a rate of 12,500 to one.

Hungary became a battleground in the latter stages of WW2, between the military forces of Nazi Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. 90% of Hungarian industrial capacity was damaged, half of it destroyed altogether. Transportation was difficult with most of the nation’s rail capacity, damaged or destroyed. What remained was either carted off to Germany or seized by the Russians, as reparations.

The loss of all that productive capacity led to scarcity of goods, and prices began to rise. The government responded by printing money. Total currency in circulation in July 1945 stood at 25 billion Pengö. Money supply rose to 1.65 trillion by January, 65 quadrillion and 47 septillion July. That’s a Trillion Trillion. Twenty-four zeroes.

47,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000.00

Banks received low rate loans, so that money could be loaned to companies to rebuild. The government hired workers directly, giving out loans to others and in many cases, outright grants. The country was flooded with money, the stuff virtually grew on trees, but there was nothing to back it up.

Inflation took a straight line into the stratosphere. An item that cost 379 Pengö in September 1945, cost 1,872,910 by March, 35,790,276 in April, and 862 billion in June. Inflation neared 150,000% per day as the currency became all but worthless. Massive printing of money had accomplished the cube root of zero.

The worst hyperinflation in history peaked on July 10, 1946, when that 379 Pengö item back in September, cost 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000.

The government responded by changing the name, and the color, of the currency. The Pengö was replaced by the Milpengö (1,000,000 Pengö), which was replaced by the Bilpengö (1,000,000,000,000) and finally the (supposedly) inflation-indexed Adopengö. The spiral resulted in the largest denominated note in history: the Milliard Bilpengö. A Billion Trillion Pengö.

The thing was worth twelve cents.

One more currency replacement and all that Keynesian largesse would finally stabilize the currency, but at what price? Real wages were reduced by 80%. If you were owed money you were wiped out. The fate of the nation was sealed when communists seized power in 1949. Hungarians could now share in that old Soviet joke. “They pretend to pay us, and we pretend to work”.

The ten worst hyperinflations in history occurred during the 20th century, including Zimbabwe in 2008, Yugoslavia 1994, Germany 1923, Greece 1944, Poland 1921, Mexico 1982, Brazil 1994, Argentina 1981, and Taiwan 1949. The common denominator in all ten were government debt, and a currency with no inherent value, except the tacit agreement of a willing buyer, and a willing seller.

In 2015, Boston University economist Laurence Kotlikoff testified before the Senate Budget Committee. “The first point I want to get across” he said, “is that our nation is broke. Our nation’s broke, and it’s not broke in 75 years or 50 years or 25 years or 10 years. It’s broke today”. Kotlikoff went on to describe the “fiscal gap”, the difference between US’ projected revenue, and the obligations our government has saddled us with. “We have a $210 trillion fiscal gap at this point”, Kotlikoff said. 11.6 times GDP – the total of all goods and services produced in the United States.

US fiscal operating debt stood at 18 trillion dollars when Professor Kotlikoff testified before congress. That’s just the on-the-books stuff. We are now north of twenty-eight, seemingly hell-bent, for thirty. The printing presses are working overtime, our currency is unmoored from any objective value.

What could go wrong?

Adults had no interest in the minuscule income, and left the newsboys (and girls) to their own devices. “Newsies” bought papers at discounted prices and peddled them on the street. Others worked saloons and houses of prostitution. They weren’t allowed to return any left unsold, and worked well into the night to sell every paper.

Adults had no interest in the minuscule income, and left the newsboys (and girls) to their own devices. “Newsies” bought papers at discounted prices and peddled them on the street. Others worked saloons and houses of prostitution. They weren’t allowed to return any left unsold, and worked well into the night to sell every paper. For all that, newsies earned about 30¢ a day. Enough for a bite to eat, to afford enough papers to do it again the following day, and maybe a 5¢ bed in the newsboy’s home.

For all that, newsies earned about 30¢ a day. Enough for a bite to eat, to afford enough papers to do it again the following day, and maybe a 5¢ bed in the newsboy’s home.

Frank Bench, a personal friend of the inventor, was the first to install the machine. The first pre-sliced loaf was sold in July of the following year. Customers loved the convenience and Bench’s bread sales shot through the roof.

Frank Bench, a personal friend of the inventor, was the first to install the machine. The first pre-sliced loaf was sold in July of the following year. Customers loved the convenience and Bench’s bread sales shot through the roof.

Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution includes the “Commerce Clause”, permitting the Congress “To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes”. That’s it.

Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution includes the “Commerce Clause”, permitting the Congress “To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes”. That’s it. The United States Supreme Court, apparently afraid of President Roosevelt and his aggressive and illegal “

The United States Supreme Court, apparently afraid of President Roosevelt and his aggressive and illegal “ The stated reasons for the ban never did make sense. At various times, Wickard claimed that it was to conserve wax paper, wheat or steel, but one reason was goofier than the one before. According to the War Production Board, most bakeries had plenty of wax paper supplies on hand, even if they didn’t buy any. Furthermore, the federal government had a billion bushels of wheat stockpiled at the time, about two years’ supply, and the amount of steel saved by not making bread slicers has got to be marginal, at best.

The stated reasons for the ban never did make sense. At various times, Wickard claimed that it was to conserve wax paper, wheat or steel, but one reason was goofier than the one before. According to the War Production Board, most bakeries had plenty of wax paper supplies on hand, even if they didn’t buy any. Furthermore, the federal government had a billion bushels of wheat stockpiled at the time, about two years’ supply, and the amount of steel saved by not making bread slicers has got to be marginal, at best.

History records 58 such instances of hyperinflation. The economic train wreck socialism has wrought on Venezuela, constitutes #59. This in a country with the largest proven oil reserves on the planet.

History records 58 such instances of hyperinflation. The economic train wreck socialism has wrought on Venezuela, constitutes #59. This in a country with the largest proven oil reserves on the planet. The assistance of French King Louis XIV was invaluable to Revolution-era Americans, at a time when colonial inflation rates approached 50% per month. Even so, French state income was only about 357 million livres at that time, with expenses exceeding one-half Billion.

The assistance of French King Louis XIV was invaluable to Revolution-era Americans, at a time when colonial inflation rates approached 50% per month. Even so, French state income was only about 357 million livres at that time, with expenses exceeding one-half Billion. Paper money crashed in the post-Revolutionary Articles of Confederation period as well, when you could buy a live sheep for two silver dollars, or 150 “Continental” (paper) dollars.

Paper money crashed in the post-Revolutionary Articles of Confederation period as well, when you could buy a live sheep for two silver dollars, or 150 “Continental” (paper) dollars. While the French third Republic levied an income tax to pay for the “Great War”, the Kaiser suspended the gold standard and fought the war on credit, believing he’d get it back from conquered territories.

While the French third Republic levied an income tax to pay for the “Great War”, the Kaiser suspended the gold standard and fought the war on credit, believing he’d get it back from conquered territories. The thing was worth twelve cents.

The thing was worth twelve cents. In 2015, Boston University economist Laurence Kotlikoff testified before the Senate Budget Committee. “The first point I want to get across” he said, “is that our nation is broke. Our nation’s broke, and it’s not broke in 75 years or 50 years or 25 years or 10 years. It’s broke today”. Kotlikoff went on to describe a “fiscal gap”, the difference between US’ projected revenue, and the obligations our government has saddled us with. “We have a $210 trillion fiscal gap at this point”. Nearly twelve times GDP – the sum total of all goods and services produced in the United States.

In 2015, Boston University economist Laurence Kotlikoff testified before the Senate Budget Committee. “The first point I want to get across” he said, “is that our nation is broke. Our nation’s broke, and it’s not broke in 75 years or 50 years or 25 years or 10 years. It’s broke today”. Kotlikoff went on to describe a “fiscal gap”, the difference between US’ projected revenue, and the obligations our government has saddled us with. “We have a $210 trillion fiscal gap at this point”. Nearly twelve times GDP – the sum total of all goods and services produced in the United States.

For the American colonies, the conflict took the form of the French and Indian War. Across the “pond”, the never-ending succession of English wars meant that, not only were colonists left alone to run their own affairs, but individual colonists learned an interdependence of one upon another, resulting in significant economic growth during every decade of the 1700s.

For the American colonies, the conflict took the form of the French and Indian War. Across the “pond”, the never-ending succession of English wars meant that, not only were colonists left alone to run their own affairs, but individual colonists learned an interdependence of one upon another, resulting in significant economic growth during every decade of the 1700s.

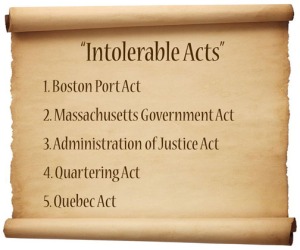

7,000 gathered at Old South Meeting House on December 16th, 1773, the last day of deadline, for Dartmouth’s cargo. Royal Governor Hutchinson held his ground, refusing the vessel permission to leave. Adams announced that “This meeting can do nothing further to save the country.”

7,000 gathered at Old South Meeting House on December 16th, 1773, the last day of deadline, for Dartmouth’s cargo. Royal Governor Hutchinson held his ground, refusing the vessel permission to leave. Adams announced that “This meeting can do nothing further to save the country.”

Boston by British troops. Minutemen clashed with “Lobster backs” a few months later, on April 19, 1775. When it was over, eight Lexington men lay dead or dying, another ten wounded. One British soldier was wounded. No one alive today knows who fired the first shot at Lexington Green. History would remember the events of that day as “

Boston by British troops. Minutemen clashed with “Lobster backs” a few months later, on April 19, 1775. When it was over, eight Lexington men lay dead or dying, another ten wounded. One British soldier was wounded. No one alive today knows who fired the first shot at Lexington Green. History would remember the events of that day as “

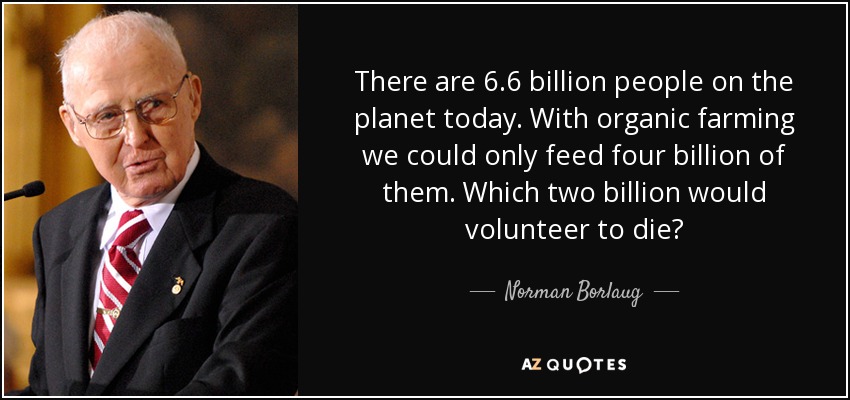

Borlaug earned his Bachelor of Science in Forestry, in 1937. Nearing the end of his undergraduate education, he attended a lecture by Professor Elvin Charles Stakman discussing plant rust disease, a parasitic fungus which feeds on phytonutrients in wheat, oats, and barley crops.

Borlaug earned his Bachelor of Science in Forestry, in 1937. Nearing the end of his undergraduate education, he attended a lecture by Professor Elvin Charles Stakman discussing plant rust disease, a parasitic fungus which feeds on phytonutrients in wheat, oats, and barley crops.

A tall, bearded peasant was spokesman. His two sons and the rest of the men and women nodded approval at every word. The little crippled boy stood with his right hand on his crutch, translating everything he said into Russian for me, word by word.

A tall, bearded peasant was spokesman. His two sons and the rest of the men and women nodded approval at every word. The little crippled boy stood with his right hand on his crutch, translating everything he said into Russian for me, word by word.

Harding’s Treasury Secretary, Andrew Mellon, believed that money was driven underground or overseas as income tax rates increased. Mellon held the heretical belief for that time, that lower tax rates led to greater levels of economic activity and that, as people had more of their own money to work with, increased activity resulted in higher tax revenues.

Harding’s Treasury Secretary, Andrew Mellon, believed that money was driven underground or overseas as income tax rates increased. Mellon held the heretical belief for that time, that lower tax rates led to greater levels of economic activity and that, as people had more of their own money to work with, increased activity resulted in higher tax revenues.

Fears of the Smoot-Hawley tariff act fueled a further contraction in the following weeks, for apparently good reason. When President Hoover signed the protectionist measure into law in 1930, American imports and exports plunged by more than half.

Fears of the Smoot-Hawley tariff act fueled a further contraction in the following weeks, for apparently good reason. When President Hoover signed the protectionist measure into law in 1930, American imports and exports plunged by more than half.

You must be logged in to post a comment.