Hannah Reitsch wanted to fly. Born March 29, 1912 into an upper-middle-class family in Hirschberg, Silesia, it’s all she ever thought about. At the age of four, she tried to jump off the family balcony, to experience flight. In her 1955 autobiography The Sky my Kingdom, Reitsch wrote: ‘The longing grew in me, grew with every bird I saw go flying across the azure summer sky, with every cloud that sailed past me on the wind, till it turned to a deep, insistent homesickness, a yearning that went with me everywhere and could never be stilled.’

Reitsch began flying gliders in 1932, as the treaty of Versailles prohibited anyone flying “war planes” in Germany. In 1934, she broke the world’s altitude record for women (9,184 feet). In 1936, Reitsch was working on developing dive brakes for gliders, when she was awarded the honorary rank of Flugkapitän, the first woman ever so honored. In 1937 she became a Luftwaffe civilian test pilot. She would hold the position until the end of WW2.

Reitsch began flying gliders in 1932, as the treaty of Versailles prohibited anyone flying “war planes” in Germany. In 1934, she broke the world’s altitude record for women (9,184 feet). In 1936, Reitsch was working on developing dive brakes for gliders, when she was awarded the honorary rank of Flugkapitän, the first woman ever so honored. In 1937 she became a Luftwaffe civilian test pilot. She would hold the position until the end of WW2.

A German Nationalist who believed she owed her allegiance to the Fatherland more than to any party, Reitsch was patriotic and loyal, and more than a little politically naive. Her work brought her into contact with the highest levels of Nazi party officialdom. Like the victims of Soviet purges who went to their death believing that it would all stop “if only Stalin knew”, Reitsch refused to believe that Hitler had anything to do with events such as the Kristallnacht pogrom. She dismissed any talk of concentration camps, as “mere propaganda”.

As a test pilot, Reitsch won an Iron Cross, Second Class, for risking her life in an attempt to cut British barrage-balloon cables. On one test flight of the rocket powered Messerschmitt 163 Komet in 1942, she flew the thing at speeds of 500 mph, a speed nearly unheard of at the time. She spun out of control and crash-landed on her 5th flight, leaving her with severe injuries. Her nose was all but torn off, her skull fractured in four places. Two facial bones were broken, and her upper and lower jaws out of alignment. Even then, she managed to write down what had happened, before she collapsed.

Doctors did not expect her to live, let alone fly again. She spent five months in hospital, and suffered from debilitating dizzy spells. She put herself on a program of climbing trees and rooftops, to regain her sense of balance. Soon, she was test flying again.

Doctors did not expect her to live, let alone fly again. She spent five months in hospital, and suffered from debilitating dizzy spells. She put herself on a program of climbing trees and rooftops, to regain her sense of balance. Soon, she was test flying again.

On this day in 1944, Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring awarded her a special diamond-encrusted version of the Gold Medal for Military Flying. Adolf Hitler personally awarded her an Iron Cross, First Class, the first and only woman in German history, so honored.

It was while receiving this second Iron Cross in Berchtesgaden, that Reitsch suggested the creation of a Luftwaffe suicide squad, “Operation Self Sacrifice”.

Hitler was initially put off by the idea, though she finally persuaded him to look into modifying a Messerschmitt Me-328B fighter for the purpose. Reitsch put together a suicide group, becoming the first to take the pledge, though the idea would never take shape. The pledge read, in part: “I hereby voluntarily apply to be enrolled in the suicide group as a pilot of a human glider-bomb. I fully understand that employment in this capacity will entail my own death.”

Hitler was initially put off by the idea, though she finally persuaded him to look into modifying a Messerschmitt Me-328B fighter for the purpose. Reitsch put together a suicide group, becoming the first to take the pledge, though the idea would never take shape. The pledge read, in part: “I hereby voluntarily apply to be enrolled in the suicide group as a pilot of a human glider-bomb. I fully understand that employment in this capacity will entail my own death.”

The plan came to an abrupt halt when an Allied bombing raid wiped out the factory in which the prototype Me-328s were being built.

In the last days of the war, Hitler dismissed his designated successor Hermann Göring, over a telegram in which the Luftwaffe head requested permission to take control of the crumbling third Reich. Hitler appointed Generaloberst Robert Ritter von Greim, ordering Hannah to take him out of Berlin and giving each a vial of cyanide, to be used in the event of capture. The Arado Ar 96 left the improvised airstrip on the evening of April 28, under small arms fire from Soviet troops. It was the last plane to leave Berlin. Two days later, Adolf Hitler was dead.

Taken into American custody on May 9, Reitsch and von Greim repeated the same statement to American interrogators: “It was the blackest day when we could not die at our Führer’s side.” She spent 15 months in prison, giving detailed testimony as to the “complete disintegration’ of Hitler’s personality, during the last months of his life. She was found not guilty of war crimes, and released in 1946. Von Greim committed suicide, in prison.

In her 1951 memoir “Fliegen – mein leben”, (Flying is my life), Reitsch offers no moral judgement one way or the other, on Hitler or the Third Reich.

She resumed flying competitions in 1954, opening a gliding school in Ghana in 1962. She later traveled to the United States, where she met Igor Sikorsky and Neil Armstrong, and even John F. Kennedy.

Hannah Reitsch remained a controversial figure, due to her ties with the Third Reich. Shortly before her death in 1979, she responded to a description someone had written of her, as `Hitler’s girlfriend’. “I had been picked for this mission” she wrote, “because I was a pilot…I can only assume that the inventor of these accounts did not realize what the consequences would be for my life. Ever since then I have been accused of many things in connection with the Third Reich”.

Toward the end of her life, she was interviewed by the Jewish-American photo-journalist, Ron Laytner. Even then she was defiant: “And what have we now in Germany? A land of bankers and car-makers. Even our great army has gone soft. Soldiers wear beards and question orders. I am not ashamed to say I believed in National Socialism. I still wear the Iron Cross with diamonds Hitler gave me. But today in all Germany you can’t find a single person who voted Adolf Hitler into power … Many Germans feel guilty about the war. But they don’t explain the real guilt we share – that we lost“.

Toward the end of her life, she was interviewed by the Jewish-American photo-journalist, Ron Laytner. Even then she was defiant: “And what have we now in Germany? A land of bankers and car-makers. Even our great army has gone soft. Soldiers wear beards and question orders. I am not ashamed to say I believed in National Socialism. I still wear the Iron Cross with diamonds Hitler gave me. But today in all Germany you can’t find a single person who voted Adolf Hitler into power … Many Germans feel guilty about the war. But they don’t explain the real guilt we share – that we lost“.

Hannah Reitsch died in Frankfurt on August 24, 1979, of an apparent heart attack. Former British test pilot and Royal Navy officer Eric Brown received a letter from her earlier that month, in which she wrote, “It began in the bunker, there it shall end.” There was no autopsy, or at least there’s no report of one. Brown, for one, believes that after all those years, she may have finally taken that cyanide capsule.

The Father/Son team tee’d off in match against the brothers Willie and Mungo Park on September 11, 1875. With two holes to go, Young Tom received a telegram with upsetting news. His wife Margaret had gone into a difficult labor. The Morrises finished those last two holes winning the match, and hurried home by ship across the Firth of Forth and up the coast. Too late. Tom Morris Jr. got home to find that his young wife and newborn baby, had died in childbirth.

The Father/Son team tee’d off in match against the brothers Willie and Mungo Park on September 11, 1875. With two holes to go, Young Tom received a telegram with upsetting news. His wife Margaret had gone into a difficult labor. The Morrises finished those last two holes winning the match, and hurried home by ship across the Firth of Forth and up the coast. Too late. Tom Morris Jr. got home to find that his young wife and newborn baby, had died in childbirth.

The military and governing structure of the time was based on a rigid and inflexible class system, placing the feudal lords or daimyō at the top, followed by a warrior-caste of samurai, and a lower caste of merchants and artisans. At the bottom of it all stood some 80% of the population, the peasant farmer forbidden to engage in non-agricultural work, and expected to provide the income to make the whole system work.

The military and governing structure of the time was based on a rigid and inflexible class system, placing the feudal lords or daimyō at the top, followed by a warrior-caste of samurai, and a lower caste of merchants and artisans. At the bottom of it all stood some 80% of the population, the peasant farmer forbidden to engage in non-agricultural work, and expected to provide the income to make the whole system work. In time, these internal Japanese issues and the growing pressure of western encroachment led to the end of the Tokugawa period and the restoration of the Meiji Emperor, in 1868. The divisions would last, well into the 20th century.

In time, these internal Japanese issues and the growing pressure of western encroachment led to the end of the Tokugawa period and the restoration of the Meiji Emperor, in 1868. The divisions would last, well into the 20th century.

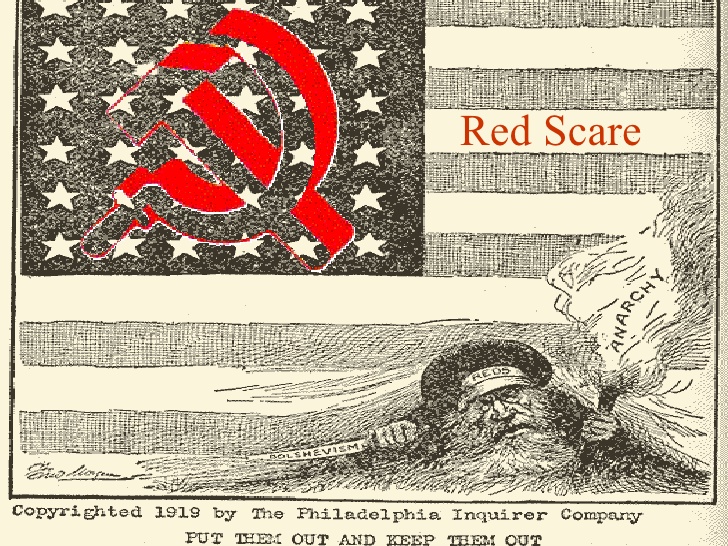

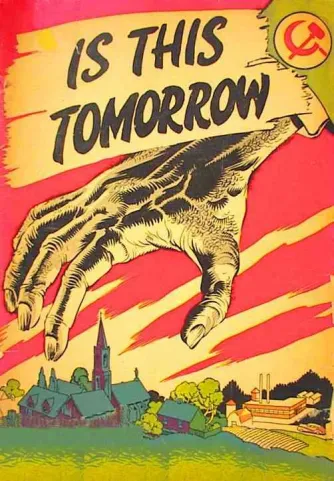

Far-left anarchists mailed no fewer than 36 dynamite bombs to prominent political and business leaders in April 1919, alone. In June, another nine far more powerful bombs destroyed churches, police stations and businesses.

Far-left anarchists mailed no fewer than 36 dynamite bombs to prominent political and business leaders in April 1919, alone. In June, another nine far more powerful bombs destroyed churches, police stations and businesses. To this day there are those who describe the period as the “First Red Scare”, as a way to ridicule the concerns of the era. The criticism seems unfair. The thing about history, is that we know how their story ends. The participants don’t, any more than we know what the future holds for ourselves.

To this day there are those who describe the period as the “First Red Scare”, as a way to ridicule the concerns of the era. The criticism seems unfair. The thing about history, is that we know how their story ends. The participants don’t, any more than we know what the future holds for ourselves.

Before defecting from the Left, Chambers had secreted documents and microfilms, some of which he hid inside a pumpkin at his Maryland farm. The collection was known as the “Pumpkin Papers”, consisting of incriminating documents, written in what appeared to Hiss’ own hand, or typed on his Woodstock no. 230099 typewriter.

Before defecting from the Left, Chambers had secreted documents and microfilms, some of which he hid inside a pumpkin at his Maryland farm. The collection was known as the “Pumpkin Papers”, consisting of incriminating documents, written in what appeared to Hiss’ own hand, or typed on his Woodstock no. 230099 typewriter. Hiss’ theory never explained why Chambers side needed another typewriter, if they’d had the original long enough to mimic its imperfections with a second.

Hiss’ theory never explained why Chambers side needed another typewriter, if they’d had the original long enough to mimic its imperfections with a second.

Though Wilson didn’t mention it directly, HMS Lusitania had been torpedoed only three days earlier with the loss of 1,198, 128 of whom were Americans.

Though Wilson didn’t mention it directly, HMS Lusitania had been torpedoed only three days earlier with the loss of 1,198, 128 of whom were Americans. The reaction to the Lusitania sinking was immediate and vehement, portraying the attack as the act of barbarians and huns and demanding a German return to “prize rules”, requiring submarines to surface and search merchantmen while placing crews and passengers in “a place of safety”.

The reaction to the Lusitania sinking was immediate and vehement, portraying the attack as the act of barbarians and huns and demanding a German return to “prize rules”, requiring submarines to surface and search merchantmen while placing crews and passengers in “a place of safety”. The American cargo vessel SS Housatonic was stopped off the southwest coast of England on February 3, and boarded by German submarine U-53. Captain Thomas Ensor was interviewed by Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose, who explained he was sorry, but Housatonic was “carrying food supplies to the enemy of my country”. She would be destroyed. The American Captain and crew were allowed to launch lifeboats and abandon ship, while German sailors raided the American’s soap supplies. Apparently, WWI-vintage German subs were short on soap.

The American cargo vessel SS Housatonic was stopped off the southwest coast of England on February 3, and boarded by German submarine U-53. Captain Thomas Ensor was interviewed by Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose, who explained he was sorry, but Housatonic was “carrying food supplies to the enemy of my country”. She would be destroyed. The American Captain and crew were allowed to launch lifeboats and abandon ship, while German sailors raided the American’s soap supplies. Apparently, WWI-vintage German subs were short on soap. President Woodrow Wilson retaliated, breaking off diplomatic relations with Germany the following day. Three days later, a German U-boat fired two torpedoes at the

President Woodrow Wilson retaliated, breaking off diplomatic relations with Germany the following day. Three days later, a German U-boat fired two torpedoes at the  The contents of Zimmermann’s note were published in the American media on March 1. Even then, there was considerable antipathy toward the British side, particularly among Americans of German and Irish ethnicity. “Who says this thing is genuine, anyway”, they might have said. “Maybe it’s a British forgery”.

The contents of Zimmermann’s note were published in the American media on March 1. Even then, there was considerable antipathy toward the British side, particularly among Americans of German and Irish ethnicity. “Who says this thing is genuine, anyway”, they might have said. “Maybe it’s a British forgery”.

Estimates of the Alamo garrison have ranged between 189 and 257 at this stage, but current sources indicate that defenders never numbered more than 200.

Estimates of the Alamo garrison have ranged between 189 and 257 at this stage, but current sources indicate that defenders never numbered more than 200.

Eminent domain exists for a purpose, but the most extreme care should be taken in its use. Plaintiffs argued that this was not a “public use”, but rather a private corporation using the power of government to take their homes for economic development, a violation of both the takings clause of the 5th amendment and the due process clause of the 14th.

Eminent domain exists for a purpose, but the most extreme care should be taken in its use. Plaintiffs argued that this was not a “public use”, but rather a private corporation using the power of government to take their homes for economic development, a violation of both the takings clause of the 5th amendment and the due process clause of the 14th. Clarence Thomas took an originalist view, stating that the majority opinion had confused “Public Use” with “Public Purpose”. “Something has gone seriously awry with this Court’s interpretation of the Constitution“, Thomas wrote. “Though citizens are safe from the government in their homes, the homes themselves are not“. Antonin Scalia concurred, seeing any tax advantage to the municipality as secondary to the taking itself.

Clarence Thomas took an originalist view, stating that the majority opinion had confused “Public Use” with “Public Purpose”. “Something has gone seriously awry with this Court’s interpretation of the Constitution“, Thomas wrote. “Though citizens are safe from the government in their homes, the homes themselves are not“. Antonin Scalia concurred, seeing any tax advantage to the municipality as secondary to the taking itself.

Some 70 charges were made against her by the pro-English Bishop of Beauvais, Pierre Cauchon, including witchcraft, heresy, and perjury.

Some 70 charges were made against her by the pro-English Bishop of Beauvais, Pierre Cauchon, including witchcraft, heresy, and perjury. After fifteen such interrogations her inquisitors still had nothing on her, save for the wearing of soldier’s garb, and her visions. Yet, the outcome of her “trial” was already determined. She was found guilty of heresy, and sentenced to be burned at the stake.

After fifteen such interrogations her inquisitors still had nothing on her, save for the wearing of soldier’s garb, and her visions. Yet, the outcome of her “trial” was already determined. She was found guilty of heresy, and sentenced to be burned at the stake.

Imperial Japan would rage for another 33 years.

Imperial Japan would rage for another 33 years.

Several went on to fight for the Viet Minh against French troops in Indochina.

Several went on to fight for the Viet Minh against French troops in Indochina.

On February 7, the 71st Infantry and supporting tanks reached Ramree town where they found determined Japanese resistance, the town falling two days later. Naval forces blockaded small tributaries called “chaungs”, which the retreating Japanese used in their flight to the mainland. A Japanese air raid damaged an allied destroyer on the 11th as a flotilla of small craft crossed the strait, to rescue survivors of the garrison. By February 17, Japanese resistance had come to an end.

On February 7, the 71st Infantry and supporting tanks reached Ramree town where they found determined Japanese resistance, the town falling two days later. Naval forces blockaded small tributaries called “chaungs”, which the retreating Japanese used in their flight to the mainland. A Japanese air raid damaged an allied destroyer on the 11th as a flotilla of small craft crossed the strait, to rescue survivors of the garrison. By February 17, Japanese resistance had come to an end.

You must be logged in to post a comment.