Begun on November 1, 1955, the American war in Southeast Asia lasted 19 years, 5 months and a day. On March 29, 1973, two months after signing the Paris Peace accords, the last US combat troops left South Vietnam as Hanoi freed the remaining POWs held in North Vietnam.

It was the longest war in American history, until Afghanistan.

Jan Scruggs served in that war. Two tours, returning home with a Purple Heart and three army commendation medals as well as a medal for valor. Theirs was an unpopular war. Like many he found readjustment to civilian life, difficult.

In 1979 he and Becky, his wife of five years, went to see a movie. The Deer Hunter. The film seemed to bring it all back. The RPG that had left him so grievously wounded. The accidental explosion of those mortar rounds that had killed his buddies. Twelve of them.

That night passed without sleep, a waking nightmare of flashbacks and alcohol. By dawn he’d envisioned a memorial. With names on it. Maybe an obelisk. On the Mall, in Washington DC. Becky feared he was losing his mind.

Scruggs was working for the department of labor at the time when he took a week off, to pursue the project.

The idea received little support. The project was impractical it was said, and besides, the project would distract veterans organizations from more important work. Undaunted, Scruggs left his job to pursue the project, full time.

It was tough going. Becky was now the sole breadwinner. In two months the project raised a scant $144.50.

Always a sign of the contemptible times in which we live, the CBS Evening News ridiculed the project. Late night “comedians” joined in the mockery and yet, that CBS report attracted the attention of powerful allies. Thousands of dollars came in from not-so-powerful contributors, mostly in $5 and $10 denominations.

Chuck Hagel, then deputy administrator for the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, took interest. Likewise John Wheeler, a fellow Vietnam vet – turned attorney who’d spearheaded the effort to erect the Southeast Asia Memorial on the military academy, at West Point.

$8 million came in over the next two years and then came the competition. The actual design. There were 1,422 submissions, so many that selections were carried out in an aircraft hangar.

Much to her surprise, the winner was 1st-generation American of Chinese ancestry Maya Lin, then an undergraduate studying architecture, at Yale University.

“The Wall” was dedicated on this day. November 13, 1982.

Lin’s design takes the form of a black granite wall, 493½-feet long and 10-feet, 3-inches high at its peak, laid out in a great wedge of stone seeming to rise from the earth and return to it. The name of every person lost in the war in Vietnam sandblasted onto stone, appearing in the order in which they were killed.

Go to the highest point on the memorial, panel 1E, the very first name is that of Air Force Tech Sgt. Richard B. Fitzgibbon, Jr. of Stoneham, Massachusetts, killed on June 8, 1956. Some distance to his right you will find the name of Marine Corps Lance Cpl. Richard B. Fitzgibbon III, killed on Sept. 7, 1965. The Fitzgibbons are one of three Father/Son pairs so memorialized.

The names begin at the center and move outward, the east wing ending on May 25, 1968. The same day continues at the far end of the west wing, moving back toward the center at panel 1W. The last name on the wall, the last person killed in the war, meets the first. The circle is closed.

There you will find the name of Kelton Rena Turner of Los Angeles, an 18-year old Marine, killed in action on May 15, 1975 during the “Mayaguez incident”, two weeks after the evacuation of Saigon.

Approach from the east and the first name you will encounter is that of Sergeant Jessie C. Alba of Port Lavaca, Tex., who served in the 101st Airborne Division and was killed near Hue in a mortar attack. Sgt. Alba was engage to be married on the day he was killed. Mary Ann Lopez later wrote in an on-line tribute, “Even now after so many years past, I still think of him and what our lives, could of been.”

Those who go to war are never the only ones to serve and to sacrifice, on behalf of the rest of us.

Most sources list Gary L. Hall, Joseph N. Hargrove and Danny G. Marshall as the last to die in Vietnam, though their fate remains, unknown. These were United States Marines, an M-60 machine gun squad, mistakenly left behind while covering the evacuation of their comrades, from the beaches of Koh Tang Island. Their names appear along with Turner’s on panel 1W, lines 130-131.

There were 57,939 names inscribed on the Memorial when it opened in 1982. 39,996 died at age 22 or younger. 8,283 were 19 years old. The 18-year-olds are the largest age group, with 33,103. Twelve of them were 17. Five were 16. There is one name on panel 23W, line 096, that of PFC Dan Bullock, United States Marine Corps. He was 15 years old on June 7, 1969. The day he died.

Left to right: PFC Gary Hall, KIA age 19, LCPL Joseph Hargrove, KIA on his 24th birthday, Pvt Danny Marshall, KIA age 19, PFC Dan Bullock, KIA age 15

Eight names belong to women, killed while nursing the wounded. 997 soldiers were killed on their first day in Vietnam. 1,448 died on their last. There are 31 pairs of brothers on the Wall. 62 parents left to endure the loss of two sons.

As of Memorial Day 2015, there are 58,307, as the names of military personnel who succumbed to wounds sustained during the war, were added to the wall.

Over the years, the Wall has inspired a number of tributes, including a traveling 3/5ths scale model of the original and countless smaller ones, bringing the grandeur of Lin’s design to untold numbers without the means or the opportunity, to travel to the nation’s capital.

In South Lyons Michigan, the black marble Michigan War Dog Memorial pays tribute to the names and tattoo numbers of 4,234 “War Dogs” who served in Southeast Asia, the vast majority of whom were left behind as “surplus equipment”.

There is even a Vietnam Veterans Dog Tag Memorial, at the Harold Washington Library, in Chicago.

Ten years ago, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, www.vvmf.org began work on a virtual “Wall of Faces”, where each name is remembered with a face, and a story to go with it. In 2017, the organization was still looking for 6,000+ photographs. As I write this there remain only 200, yet to be discovered.

Check it out. Pass it around. You might be able to help.

I was nine years old in May 1968, the single deadliest month of that war with 2,415 killed. All these decades later later I still recall the way so many disgraced themselves, in the way they treated those returning home from that place.

Even today as veterans of the war in Vietnam know the appreciation that is their due, the scars run deep for the recognition too often denied, those many years ago.

Now in the modern era we trust and expect our countrymen will remember. Any issue taken with US war policy, needs to brought up with the politicians who craft that policy. Not a member of the Armed Services, doing what his nation called on him to do.

Gary Childs of Paxton Massachusetts, my uncle, was one among hundreds of sailors and marines who fought to bring the fire under control. He was below decks when the fire broke out, leaving moments before his quarters were engulfed in flames. Only by that slimmest of margins did he and any number of sailors aboard the USS Forrestal on this day in 1967, escape being #135.

Gary Childs of Paxton Massachusetts, my uncle, was one among hundreds of sailors and marines who fought to bring the fire under control. He was below decks when the fire broke out, leaving moments before his quarters were engulfed in flames. Only by that slimmest of margins did he and any number of sailors aboard the USS Forrestal on this day in 1967, escape being #135.

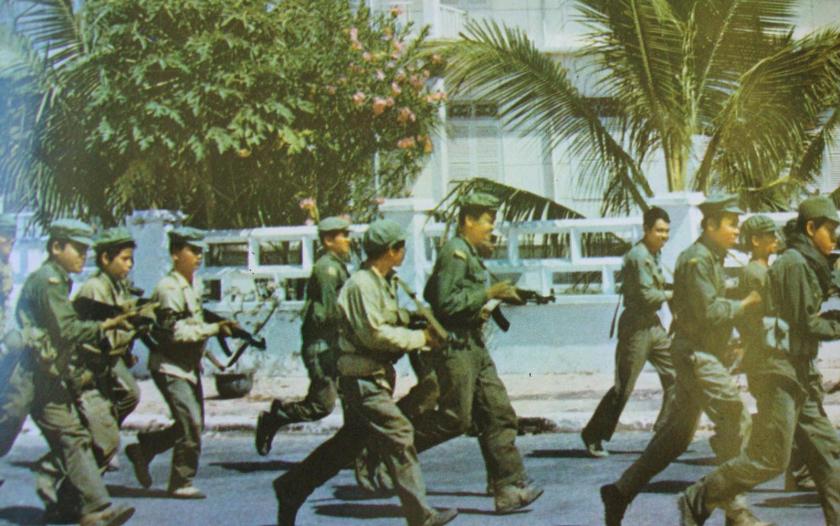

The war in Vietnam pitted as many as 1.8 million allied forces from South Vietnam, the United States, Thailand, Australia, the Philippines, Spain, South Korea and New Zealand, against about a half million from North Vietnam, China, the Soviet Union and North Korea. Begun on November 1, 1955, the conflict lasted 19 years, 5 months and a day. On March 29, 1973, two months after signing the Paris Peace accords, the last US combat troops left South Vietnam as Hanoi freed the remaining POWs held in North Vietnam.

The war in Vietnam pitted as many as 1.8 million allied forces from South Vietnam, the United States, Thailand, Australia, the Philippines, Spain, South Korea and New Zealand, against about a half million from North Vietnam, China, the Soviet Union and North Korea. Begun on November 1, 1955, the conflict lasted 19 years, 5 months and a day. On March 29, 1973, two months after signing the Paris Peace accords, the last US combat troops left South Vietnam as Hanoi freed the remaining POWs held in North Vietnam.

The humanitarian disaster that was the Indochina refugee crisis was particularly acute between 1979 – ’80, but reverberated into the 21st century.

The humanitarian disaster that was the Indochina refugee crisis was particularly acute between 1979 – ’80, but reverberated into the 21st century.

In the end, US public opinion would not sustain what too many saw as an endless war in Vietnam. We feel the political repercussions, to this day. I was ten at the time of the Tet Offensive in 1968. Even then I remember that searing sense of humiliation and disgrace, at the behavior of some fellow Americans.

In the end, US public opinion would not sustain what too many saw as an endless war in Vietnam. We feel the political repercussions, to this day. I was ten at the time of the Tet Offensive in 1968. Even then I remember that searing sense of humiliation and disgrace, at the behavior of some fellow Americans.

You must be logged in to post a comment.