In an alternate history, the June 1914 assassination of the heir-apparent to the Habsburg Empire may have led to nothing more than a regional squabble. Little more than a policing action, in the Balkans. As it was, mutual distrust and entangling alliances drew the Great Powers of Europe into the vortex. On August 3, the “War to End Wars” exploded across the European continent.

The early 20th century has been called the “Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration”, and for good reason. As the diplomatic wrangling, mobilizations and counter-mobilizations of the “period preparatory to war” advanced through July, 1914, Sir Ernest Shackleton made the final arrangements for his third expedition into the Antarctic. Despite the outbreak of war, 1st Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill ordered Shackleton to proceed. The “Endurance” expedition” departed British waters on August 8.

The German invasion of France ground to a halt that September. The first entrenchments were being dug as Shackleton himself remained in England, departing on September 27 to meet up with the Endurance expedition in Buenos Aires.

As the unofficial Christmas Truce descended over the trenches of Europe, Shackleton’s expedition slowly picked their way through the ice floes of the Weddell Sea.

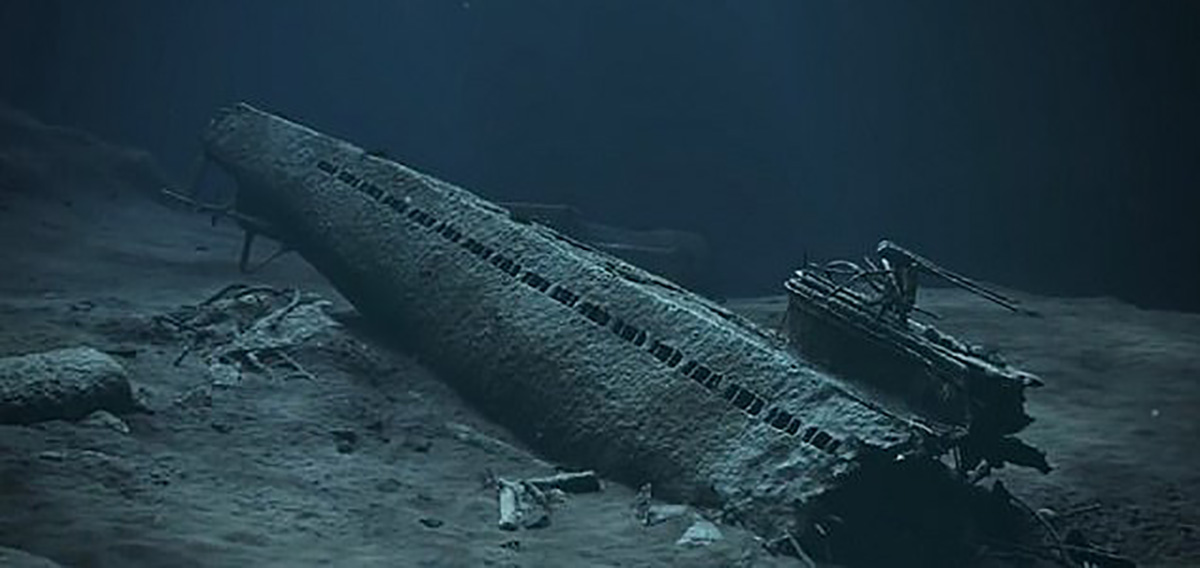

The disaster of WWI became “Total War” with the zeppelin raids of January, as Endurance met with disaster of her own. The ship was frozen fast, with no hope of escape. As the nine-month battle unfolded across the Gallipoli Peninsula, Shackleton’s men abandoned ship’s routine and converted to winter station. Finally, camps were set up across the drifting ice. On November 21, the wreck of the Endurance slipped below the surface.

In December 1915, Allies began preparations for a summer offensive along the upper reaches of the river Somme. In February, Erich von Falkenhayn began an offensive in Verdun designed to “bleed France white”. The Shackleton party was at this time camped on an ice pack, adrift in open ocean.

The ice began to break up that April, forcing Shackleton and his party into three small lifeboats. Five brutal days would come and go in those open boats, the last of 457 days spent at sea before finally reaching the desolate shores of Elephant Island.

The whaling station at South Georgia Island some 720 miles distant, was the nearest outpost of civilization. The only hope for survival. Shackleton and a party of five set out on April 24 in a 20-foot lifeboat. They shouldn’t have made it, but somehow did. In hurricane-force winds, the cliffs of South Georgia Island came into view four weeks later.

Scaling those terrible cliffs alone was a survival epic, worthy of its own story. Somehow, not a man was lost. They must have been a sight, with thick ice encrusting long, filthy beards, saltwater-soaked sealskin clothing rotting from their bodies. The first people they came across were children, who ran in fright at the sight of them. At last, on May 20, 1916, the Shackleton expedition was saved.

Like a latter-day Robinson Crusoe emerged from the frozen wastes of the Antarctic, Shackleton asked for news on the war. How it had all ended. The response came back as if every word of it, was a hammer blow.

“The war isn’t over. Millions are dead. Europe is mad. The world is mad”.

Preparatory bombardment for the Somme offensive began that June, 1,500 guns firing 1.7 million shells into a twelve-mile front. 27 shells for every foot of the front. Allies went “over the top” on July 1, the single worst day in British military history. 19,240 British soldiers were killed in that single day, along with 1,590 French. German losses numbered 10,000–12,000. By July 19, 1916, the Somme offensive was just getting started. The battle would last another 122 days.

The toll exacted by the 1st World War was cataclysmic in human, economic and environmental terms. After the war, hundreds of square miles along the north of France were identified, thusly:

“Completely devastated. Damage to properties: 100%. Damage to Agriculture: 100%. Impossible to clean. Human life impossible”.

Vast quantities of human and animal remains permeate this “Zone Rouge”, an area saturated with unexploded shells and munitions of all sizes and types: gas, high explosive, anti-personnel. There are hand grenades and bombs, small arms and rusted ammunition, by the truckload.

Lead, mercury, chlorine, arsenic and other toxins permeate the soil. In two areas near Ypres and Woëvre, arsenic constitutes up to 17% of some soil samples. The Red Zone is smaller today than it once was but, to this day, 99% of all plants still die in some of these places.

During World War 1 the two sides fired an estimated ton of explosives at each other, for every square meter of the western Front. As many as one in three shells failed to explode. The Ypres salient alone was believed to contain as many as 300 million unexploded shells at the war’s end. 87 years after the cessation of hostilities, one “Red Zone” survey uncovered up to 150 shells per 5,000 square meters in the top six inches of soil, alone.

By means of comparison, an American football field covers 5,351.215 square meters.

100 years after WW1, more than 20 members of Belgian Explosive Ordnance Disposal (DOVO) were killed in 1998, alone.

In June 2016, head of the bomb disposal unit at Amiens Michel Colling, said: “Since the start of the year we’ve been called out 300 times to dispose of 25 tons of bombs. As soon as you start turning the earth up”, Colling said, “you find them. At this rate, we have another 500 years to clear the area, so the work is far from over.”

The rotor blades from farmers’ tractors sometimes set them off. In June 2016, farmer Claude Samain plowed up a Lee-Enfield rifle. Last held in all probability by a British infantryman, the rifle was now seeing the sun for the first time, in 100 years. He placed it on a pile rusted old shells and ironworks. As a farm kid of the 1930s, Claude remembered turning up bodies in his fields. ‘We find shells every time we turn the earth over for potatoes or sugar beet.” he explained.

French farmers call the stuff, récolte de fer. Iron harvest.

That part about Claud Samain comes from a Mirror story published July 1, 2016 and written, by Andy Lines. “As Claude, 76, passed me the gun” Lines writes, “he smiled: “You Brits are so respectful of what happened here on the Somme. “Three coachloads of children arrive every single day to learn what happened 100 years ago – you never see any French children.””

Nor I would guess, any American children, and that’s a damned shame.

You must be logged in to post a comment.