“Listen my children and you shall hear,

Of the midnight ride of” …Sybil Ludington.

Wait…What?

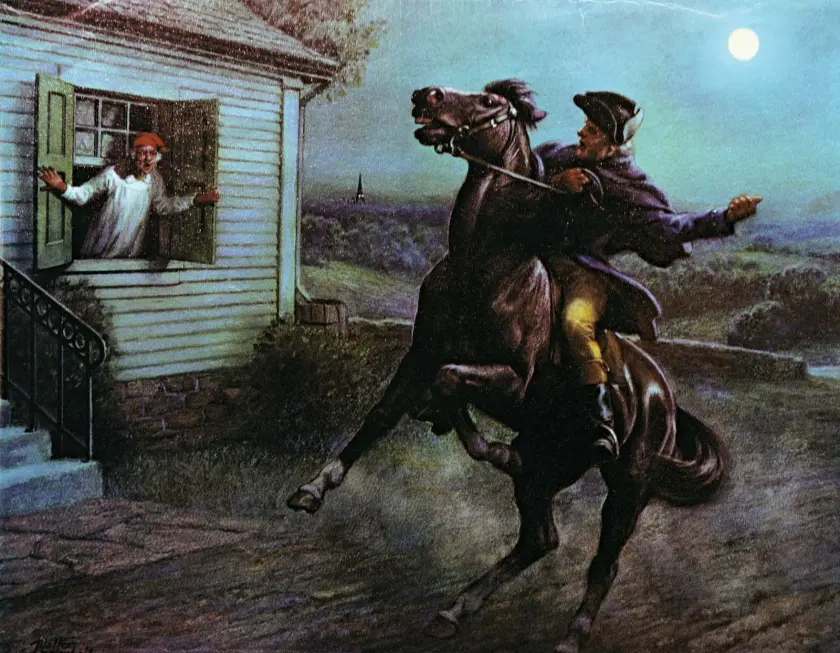

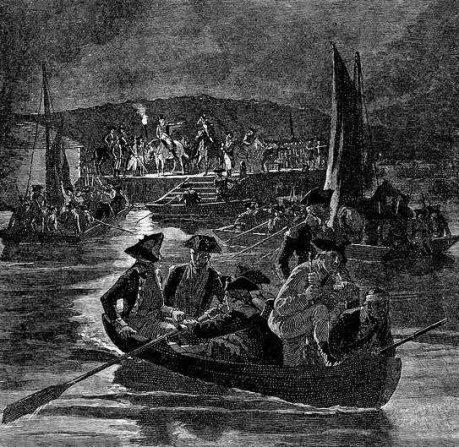

Paul Revere’s famous “midnight ride” began on the night of April 18, 1775. Revere was one of two riders, soon joined by a third, fanning out from Boston to warn of an oncoming column of “regulars”, come to destroy the stockpile of gunpowder, ammunition, and cannon located in Concord.

Revere himself covered barely 12 miles before being captured, his horse confiscated to replace the tired mount of a British sergeant. Revere would finish his “ride” on foot, arriving at sunrise on the 19th to witness the last moments of the battle on Lexington Green.

Revere himself covered barely 12 miles before being captured, his horse confiscated to replace the tired mount of a British sergeant. Revere would finish his “ride” on foot, arriving at sunrise on the 19th to witness the last moments of the battle on Lexington Green.

Two years later, Patriot forces maintained a similar supply depot in the southwest Connecticut town of Danbury.

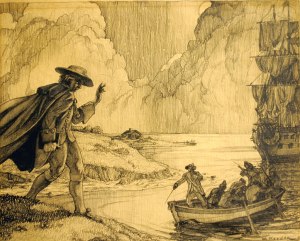

William Tryon was the Royal Governor of New York, and long-standing advocate for attacks on civilian targets. In 1777, Tryon was major-general of the provincial army. On April 25th, the General set sail for the Connecticut coast of Long Island Sound with a force of some 1,800, intending to destroy the small town.

Patriot Colonel Joseph Cooke’s small Danbury garrison was caught and quickly overpowered on the 26th, while attempting to remove food supplies, uniforms, and equipment. Facing little if any opposition, Tryon’s forces went on a bender, burning homes, farms, and storehouses. Thousands of barrels of pork, beef, and flour were destroyed, along with 5,000 pairs of shoes, 2,000 bushels of grain, and 1,600 tents.

Colonel Henry Ludington was a farmer and father of 12, with a long military career. A long-standing and loyal subject of the British crown, Ludington switched sides in 1773, joining the rebel cause and rising to command the 7th Regiment of the Dutchess County Militia, in New York’s Hudson Valley.

In April 1777, Ludington’s militia was disbanded for planting season, and spread across the countryside. An exhausted rider arrived at the Ludington farm on a blown horse on the evening of the 26th, asking for help. 15 miles away, British regulars and a force of loyalists were burning Danbury to the ground.

The Dutchess County Militia had to be called up. The Colonel had one night to prepare for battle, and this rider was done. The job would have to go to Colonel Ludington’s first-born, his daughter, Sybil.

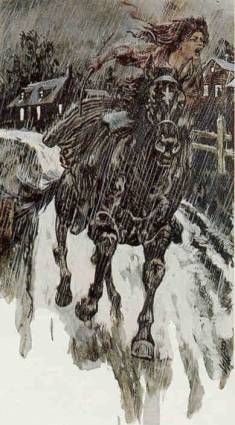

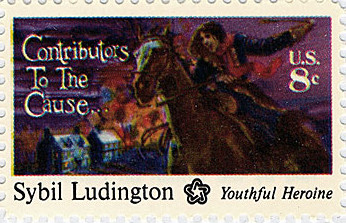

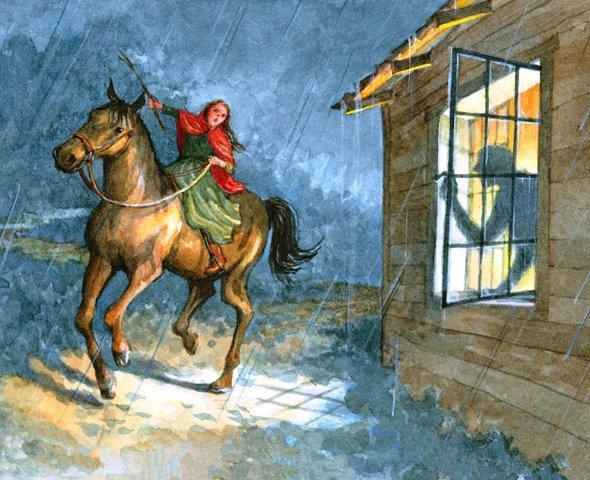

Born April 5, 1761, Sybil Ludington was barely sixteen at the time of her ride. From Poughkeepsie to what is now Putnam County and back, the “Female Paul Revere” rode across the lower Hudson River Valley, covering 40 miles in the pitch dark of night, alerting her father’s militia to the danger and urging they come out for a fight. She’d use a stick to knock on doors, even using it once to fight off a highway bandit.

By the time Sybil returned the next morning, cold, rain-soaked, and exhausted, most of 400 militia were ready to march.

Arnold’s forces arrived too late to save Danbury, but inflicted a nasty surprise on the British rearguard as the column approached nearby Ridgefield. Never outnumbered by less than three-to-one, Connecticut militia was able to slow the British advance until Ludington’s New York Militia arrived on the following day. The last phase of the action saw the same type of swarming harassment as seen on the British retreat from Concord to Boston, early in the war. 35 miles to the east of Danbury, General Benedict Arnold was gathering a force of 500 regular and irregular Connecticut militia, with Generals David Wooster and Gold Selleck Silliman.

While the British operation was a tactical success, the mauling inflicted by these colonials ensured that this was the last hostile British landing on the Connecticut coast.

The British raid on Danbury destroyed at least 19 houses and 22 stores and barns. Town officials submitted £16,000 in claims to Congress, for which town selectmen received £500 reimbursement. Further claims were made to the General Assembly of Connecticut in 1787, for which Danbury was awarded land. In Ohio.

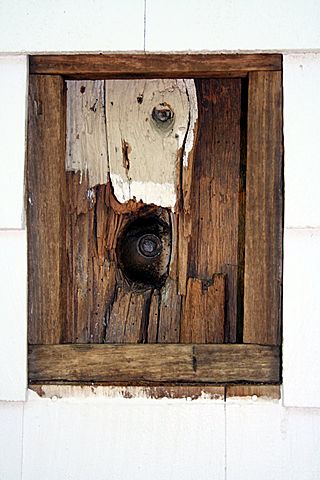

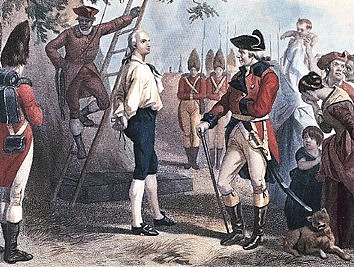

At the time, Benedict Arnold planned to travel to Philadelphia, to protest the promotion of officers junior to himself, to Major General. Arnold, who’d had two horses shot out from under him at Ridgefield, was promoted to Major General in recognition for his role in the battle. Along with that promotion came a horse, “properly caparisoned as a token of … approbation of his gallant conduct … in the late enterprize to Danbury.” For now, the pride which would one day be his undoing, was assuaged.The Keeler Tavern in Ridgefield is now a museum. The British cannonball fired into the side of the building, remains there to this day.

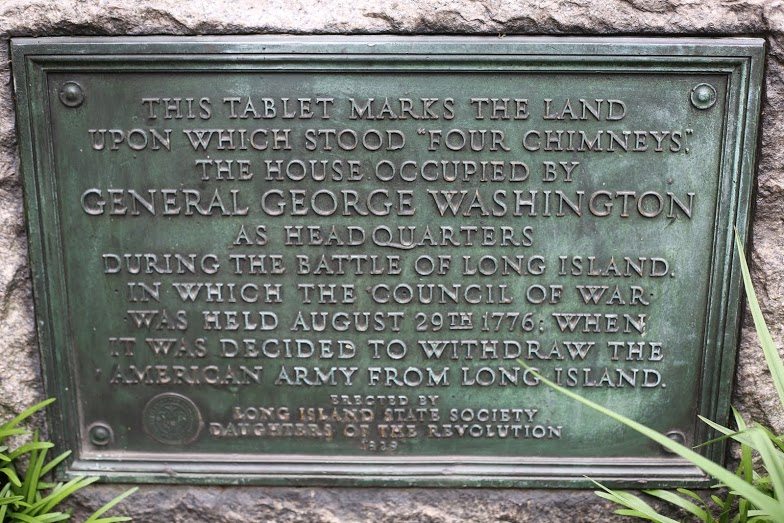

Henry Ludington would become Aide-de-Camp to General George Washington, and grandfather to Harrison Ludington, mayor of Milwaukee and 12th Governor of Wisconsin.

Gold Silliman was kidnapped with his son by a first marriage by Tory neighbors, and held for Nearly seven months at a New York farmhouse. Having no hostage of equal rank with whom to exchange for the General, Patriot forces went out and kidnapped one of their own, in the person of Chief Justice Judge Thomas Jones, of Long Island.

Mary Silliman was left to run the farm, including caring for her own midwife, who was brutally raped by English forces for denying them the use of her home. The 1993 made-for-TV movie “Mary Silliman’s War” tells the story of non-combatants, pregnant mothers and farm wives during the Revolution, as well as Mary’s own negotiations for her husband’s release from Loyalist captors.

General David Wooster was mortally wounded at the Battle of Ridgefield, moments after shouting “Come on my boys! Never mind such random shots!” Today, an archway marks the entrance to Wooster Square, in the East Rock Neighborhood of New Haven.

General David Wooster was mortally wounded at the Battle of Ridgefield, moments after shouting “Come on my boys! Never mind such random shots!” Today, an archway marks the entrance to Wooster Square, in the East Rock Neighborhood of New Haven.

Sybil Ludington received the thanks of family and friends including that of George Washington, himself. And then it was as if she had stepped off the pages of history.

Paul Revere’s famous ride would have likewise faded into obscurity, but for the poetry of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Eighty-six years, later.

“Listen my children and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive…..

In 1582, France switched from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian moving New Year to January 1 as specified by the Council of Trent, of 1563. Those who didn’t get the news and continued to celebrate New Year in late March/April 1, quickly became the butt of jokes and hoaxes.

In 1582, France switched from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian moving New Year to January 1 as specified by the Council of Trent, of 1563. Those who didn’t get the news and continued to celebrate New Year in late March/April 1, quickly became the butt of jokes and hoaxes. In Scotland, April Fools’ Day is traditionally called Hunt-the-Gowk Day. Though the term has fallen into disuse, a “gowk” is a cuckoo or a foolish person. The prank consists of asking someone to deliver a sealed message requesting unspecified assistance. The message reads “Dinna laugh, dinna smile. Hunt the gowk another mile”. On reading the message, the recipient will explain that in order to help, he’ll first need to contact another person, sending the victim on down the road with the same message.

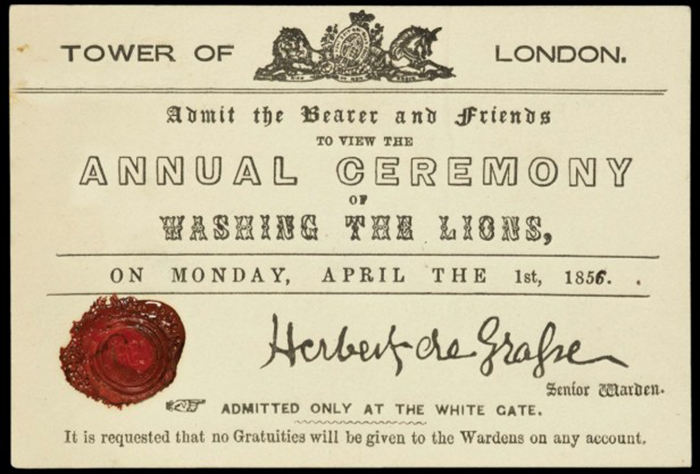

In Scotland, April Fools’ Day is traditionally called Hunt-the-Gowk Day. Though the term has fallen into disuse, a “gowk” is a cuckoo or a foolish person. The prank consists of asking someone to deliver a sealed message requesting unspecified assistance. The message reads “Dinna laugh, dinna smile. Hunt the gowk another mile”. On reading the message, the recipient will explain that in order to help, he’ll first need to contact another person, sending the victim on down the road with the same message. Animals were kept at the Tower of London since the 13th century, when Emperor Frederic II sent three leopards to King Henry III. In later years, elephants, lions and even a polar bear were added to the collection, the polar bear trained to catch fish in the Thames.

Animals were kept at the Tower of London since the 13th century, when Emperor Frederic II sent three leopards to King Henry III. In later years, elephants, lions and even a polar bear were added to the collection, the polar bear trained to catch fish in the Thames. In “Reminiscences of an Old Bohemian”, Gustave Strauss laments his complicity in the hoax in 1848. “These wretched conspirators”, as Straus called his accomplices, “had a great number of order-cards printed, admitting “bearer and friends” to the White Tower, on the 1st day of April, to witness…the famous grand annual ceremony of washing the lions”.

In “Reminiscences of an Old Bohemian”, Gustave Strauss laments his complicity in the hoax in 1848. “These wretched conspirators”, as Straus called his accomplices, “had a great number of order-cards printed, admitting “bearer and friends” to the White Tower, on the 1st day of April, to witness…the famous grand annual ceremony of washing the lions”. In 1957, (you can guess the date), the BBC reported the delightful news that mild winter weather had virtually eradicated the dread spaghetti weevil of Switzerland. Swiss farmers were now happily anticipating a bumper crop of spaghetti. Footage showed smiling Swiss, happily picking spaghetti from the trees.

In 1957, (you can guess the date), the BBC reported the delightful news that mild winter weather had virtually eradicated the dread spaghetti weevil of Switzerland. Swiss farmers were now happily anticipating a bumper crop of spaghetti. Footage showed smiling Swiss, happily picking spaghetti from the trees.

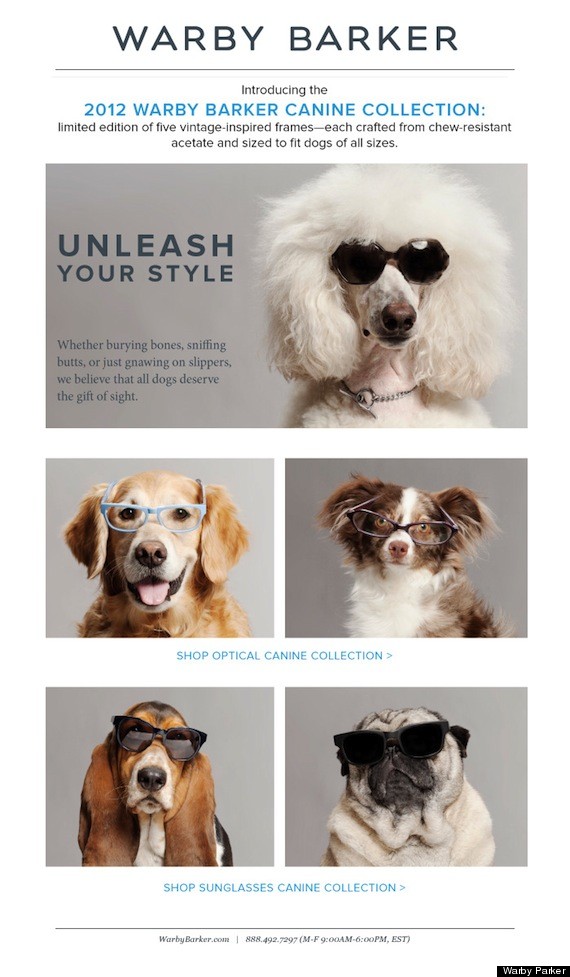

The Warby Parker Company website describes a company mission of “offer[ing] designer eyewear at a revolutionary price, while leading the way for socially conscious businesses”.

The Warby Parker Company website describes a company mission of “offer[ing] designer eyewear at a revolutionary price, while leading the way for socially conscious businesses”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.