The fifteenth child of Josiah and Abiah Franklin was born in a little house on Milk Street in Boston, across from the Old South Church.

The family moved to a larger house at Union & Hanover Street when little Benjamin was six. As the tenth son, Ben was destined to be “tithed” to the church, but Josiah changed his mind after the boy’s first year in Boston Latin School. Considering the small salary, it was too expensive to educate a minister of the church.

The boy was sent to George Brownell’s English school for writing and arithmetic where he stayed until age ten, when he went to work in his father’s shop making tallow candles and boiling soap. After that, “Dr.” Benjamin Franklin’s education came exclusively from the books he picked up along the way.

By twelve the boy was “Hankering to go to sea”. His father was concerned about his running away. Knowing of the boy’s love of books, the elder Franklin apprenticed his son to the print shop of James Franklin, one of his elder sons, where he went to work setting type for books. And reading them. He would often “borrow” a book at night, returning it “early in the Morning lest it should be miss’d or wanted.”

By 1720, James Franklin began to publish The New England Courant, the second newspaper to appear in the American colony.

Franklin often published essays and articles written by his friends, a group describing itself as “The Hell-Fire Club”. Now 16, Benjamin desperately wanted to be one of them, but James seemed to feel that little brothers should be seen and not heard.

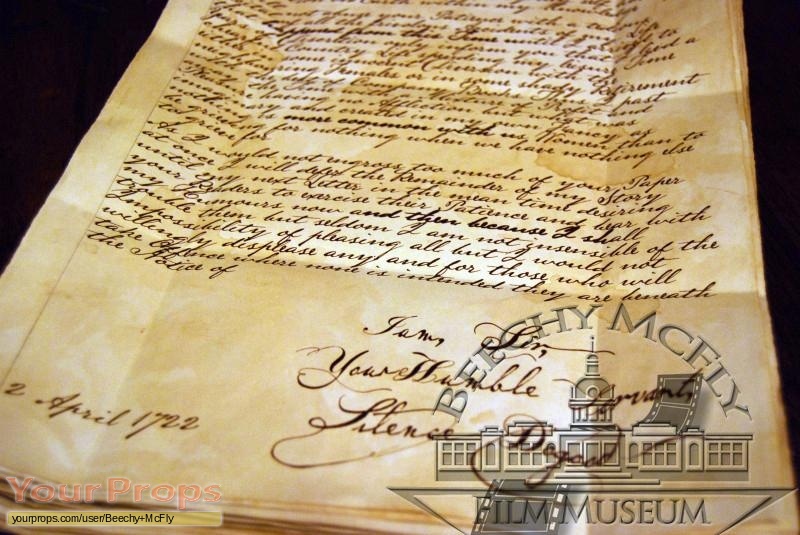

Sometime around March 1722, a letter appeared beneath the print shop door. “Sir”, the letter began, “It may not be improper in the first Place to inform your Readers, that I intend once a Fortnight to present them, by the Help of this Paper, with a short Epistle, which I presume will add somewhat to their Entertainment”. The letter went on in some detail to describe the life of its author. It was signed, Mrs. Silence Dogood.

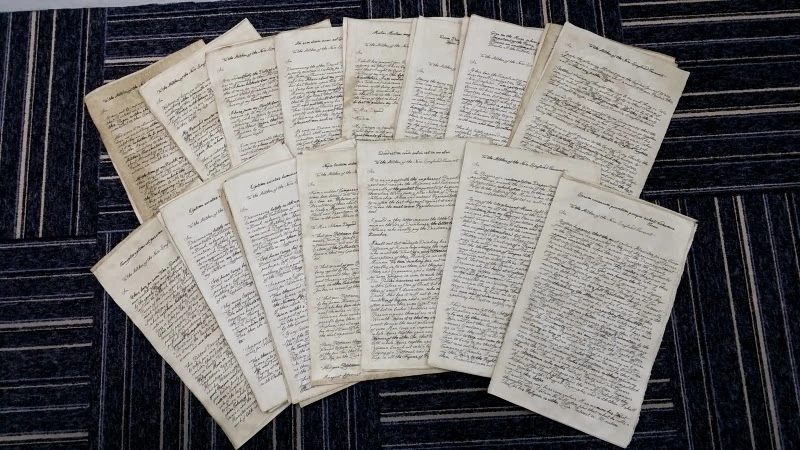

That first letter was published on April 2. True to her word, Silence Dogood wrote again in two weeks. And then again. And again. Once every other week, for over half a year. The Dogood letters were delightful, cleverly mocking the manners of Boston “Society” and freely giving advice, particularly on the way that women should be treated. Nothing was sacred. One letter suggested that the only thing students learned at Harvard College, was conceit.

James Franklin and his literary friends loved the letters, and published every one. All of Boston was charmed with Silence Dogood’s subtle mockery of the city’s Old School Puritan elite. Proposals of marriage came into the print shop, when the widow Dogood coyly suggested that she would welcome suitors.

James was jailed at one point, for printing “scandalous libel” about Massachusetts Governor Joseph Dudley. The younger Franklin ran the shop in his absence, when Mrs. Dogood came to his defense. Quoting Cato, she proclaimed: “Without freedom of thought there can be no such thing as wisdom and no such thing as public liberty without freedom of speech.”

And then the letters stopped, much to the dismay of the Courant and its readership. One wrote to the editor, saying the paper had “lost a very valuable Correspondent, and the Public been depriv’d of many profitable Amusements.”

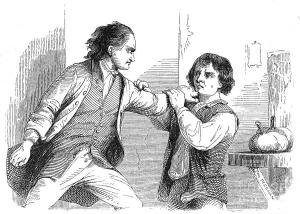

On December 3, James Franklin ran an ad. “If any Person . . . will give a true Account of Mrs. Silence Dogood, whether Dead or alive, Married or unmarried, in Town or Country, . . . they shall have Thanks for their Pains.” It was only then that his sixteen-year-old brother fessed up. Benjamin Franklin was the author of the Silence Dogood letters.

All of Boston was amused by the hoax Not James. He was so furious with his little brother, the younger Franklin broke his terms of apprenticeship and fled, to Pennsylvania.

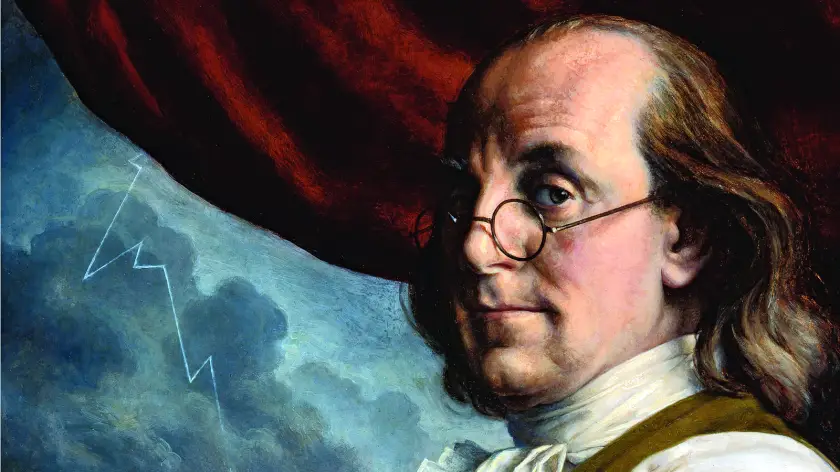

So it was a future Founding Father of the Republic, the inventor, scientist, writer and philosopher, the statesmen who appears on our $100 bill, came to Philadelphia. Within a few years, Franklin had set up his own print shop, publishing the Philadelphia Gazette as well as his own book bindery, in addition to buying and selling books.

Thanks in no small part to Franklin’s efforts, literacy standards were higher in Colonial America than among the landed gentry of 18th century England.

Franklin’s diplomacy to the Court of Versailles was every bit as important to the success of the Revolution, as the Generalship of the Father of the Republic, George Washington. Signatory to both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, it is arguably Ben Franklin who broke the impasse of the Convention of 1787, paving the way for ratification of the United States Constitution.

By that time too old and frail to deliver his own speech, Franklin had someone else read his words to the deadlocked convention.

“ON THE WHOLE, SIR, I CAN NOT HELP EXPRESSING A WISH THAT EVERY MEMBER OF THE CONVENTION WHO MAY STILL HAVE OBJECTIONS TO IT, WOULD, WITH ME, ON THIS OCCASION, DOUBT A LITTLE OF HIS OWN INFALLIBILITY, AND, TO MAKE MANIFEST OUR UNANIMITY, PUT HIS NAME TO THIS INSTRUMENT”.

Doubt a little of his own infallibility. That seems like good advice, even today.

The fifteenth child of Josiah and Abiah Franklin was born in a little house on Milk Street, across from the Old South Church, in Boston.

The fifteenth child of Josiah and Abiah Franklin was born in a little house on Milk Street, across from the Old South Church, in Boston.

James Franklin and his literary friends loved the letters, and published every one. All of Boston was charmed with Silence Dogood’s subtle mockery of the city’s Old School Puritan elite. Proposals of marriage came into the print shop, when the widow Dogood coyly suggested that she would welcome suitors.

James Franklin and his literary friends loved the letters, and published every one. All of Boston was charmed with Silence Dogood’s subtle mockery of the city’s Old School Puritan elite. Proposals of marriage came into the print shop, when the widow Dogood coyly suggested that she would welcome suitors. All of Boston was amused by the hoax, but not James. He was furious with his little brother, who soon broke the terms of his apprenticeship and fled to Pennsylvania.

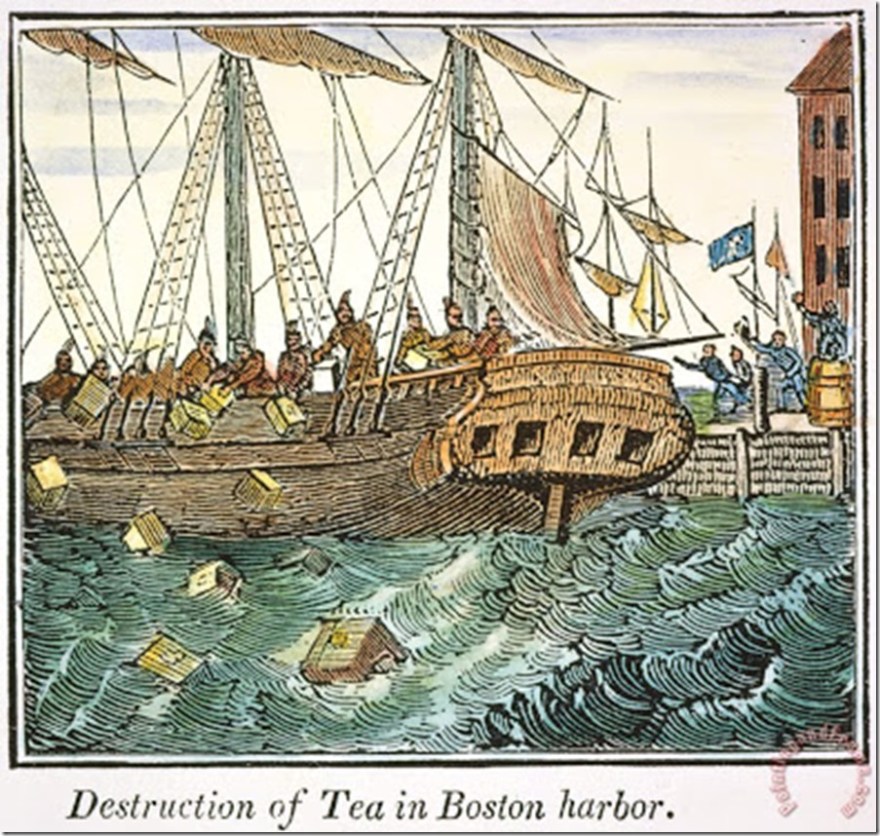

All of Boston was amused by the hoax, but not James. He was furious with his little brother, who soon broke the terms of his apprenticeship and fled to Pennsylvania. Franklin’s diplomacy to the Court of Versailles was every bit as important to the success of the Revolution, as the Generalship of the Father of the Republic, George Washington. Signatory to both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, it is arguably Ben Franklin who broke the impasse of the Convention of 1787, paving the way for ratification of the United States Constitution.

Franklin’s diplomacy to the Court of Versailles was every bit as important to the success of the Revolution, as the Generalship of the Father of the Republic, George Washington. Signatory to both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, it is arguably Ben Franklin who broke the impasse of the Convention of 1787, paving the way for ratification of the United States Constitution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.