The Roman Republic of antiquity operated on the basis of separation of powers with checks and balances, and a strong aversion to the concentration of authority. Except in times of national emergency, no single individual was allowed to wield absolute power over his fellow citizens.

The retired patrician and military leader Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus was called from his farm in 458BC to assume the mantle of Dictator and, despite his old age again, twenty years later. With the crisis averted, Cincinnatus relinquished all power and the perks which came with it, and returned to his plow.

The man’s name remains symbolic, from that day to this. A synonym for outstanding leadership, selfless service and civic virtue.

Of all the General officers who fought for American Independence, there is but one true Cincinnatus. A man who risked his life in the cause of Liberty, and truly retired from public life.

Outside of his native New Hampshire, few remember the name of John Stark. Born August 28, 1728 in Londonderry (modern day Derry), the family moved up the road when the boy was eight, to Derryfield. Today we know it as Manchester.

On April 28, 1752, 23-year-old John Stark was out trapping and fishing with his brother William, and a couple of buddies. The small group was set upon by a much larger party of Abenaki warriors. David Stinson was killed in the struggle, as John was able to warn his brother away. William escaped, in a canoe.

John was captured along with Amos Eastman. 267 years ago today, the hostages were heading north, all the way to Quebec, where the pair were subjected to a ritual torture known as “running the gauntlet”.

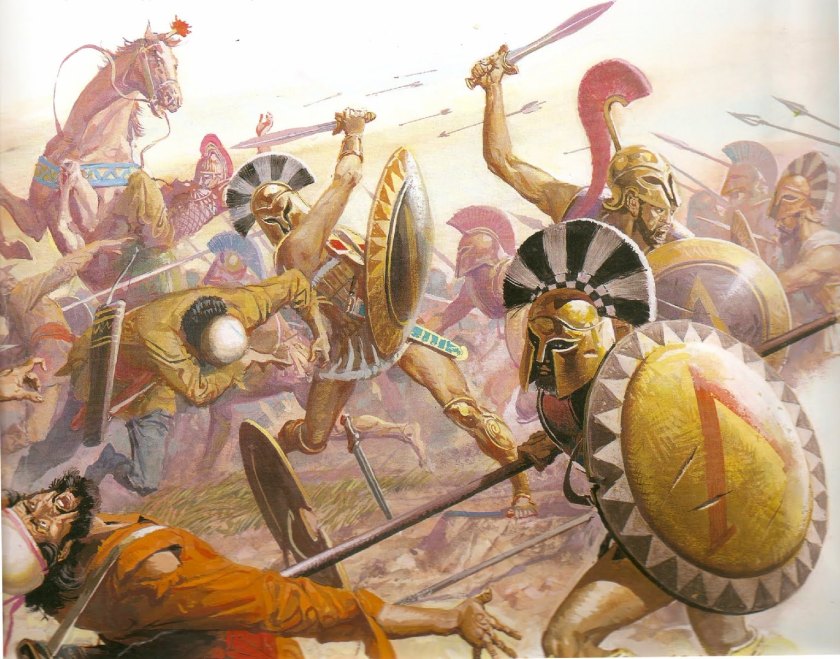

In the eastern woodlands of the United States and southern Quebec and Ontario, captives in the colonial and pre-European era often faced death by ritual torture at the hands of indigenous peoples. The process could last, for days. In running the gauntlet, the condemned is forced between two opposing rows where warriors strike out with clubs, whips and bladed weapons.

Eastman barely got out alive, but Stark wasn’t playing by the same rules. He hit the first man at a dead run, wrenching the man’s club from his grasp and striking out, at both lines. The scene was pandemonium, as the tormented captive gave as good as he got. To the chief of the Abenaki, it may have been the funniest thing, ever. He was so amused, he adopted the pair into the tribe. Eastman and Stark lived as tribal members for the rest of that year and into the following Spring, when a Massachusetts Bay agent bought their freedom. Sixty Spanish dollars for Amos and $103, for John Stark.

Seven years later during the French & Indian War, Rogers’ Rangers were ordered to attack the Abenaki village with John Stark, second in command. Stark refused to accompany the attacking force out of respect for his Indian foster family, returning instead to Derryfield and his wife Molly, whom he had married the year before.

John Stark returned to military service in 1775 following the Battles of Lexington and Concord, accepting a Colonelcy with the 1st Regiment of the New Hampshire militia.

During the early phase of the Battle of Bunker Hill, American Colonel William Prescott knew he was outgunned and outnumbered, and sent out a desperate call for reinforcements. The British warship HMS Lively was raining accurate fire down on Charlestown Neck, the narrow causeway linking the city with the rebel positions. Several companies were milling about just out of range, when Stark ordered them to step aside. Colonel Stark and his New Hampshire men then calmly marched to Prescott’s position on Breed’s Hill, without a single casualty.

Stark and his men formed the left flank of the rebel position, leading down to the beach at Mystic River. The Battle of Bunker Hill was a British victory, in that they held the ground, when it was over. It was a costly win which could scarcely be repeated. At the place in the line held by John Stark’s New Hampshire men, British dead were piled up like cord wood.

John Stark’s service record reads like a timeline of the American Revolution. The doomed invasion of Canada in the Spring of 1776. The famous crossing of the Delaware and the victorious battles at Trenton, and Princeton New Jersey. Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum and his Brunswick mercenaries ran into a buzz saw in Bennington Vermont, in the form of Seth Warner’s Green Mountain Boys and John Stark, rallying his New Hampshire militia with the cry, “There are your enemies, the Red Coats and the Tories. They are ours, or this night Molly Stark sleeps a widow!” When it was over, Stark reported 14 dead and 42 wounded. Of Lt. Col. Baum’s 374 professional soldiers, only nine walked away.

The loss of his German ally led in no small part to “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne’s defeat, at Saratoga. Stark served with distinction for the remainder of the war and, like Cincinnatus before him, returned home to his farm.

In 1809, a group of Bennington veterans gathered for a reunion. Stark was 81 at this time and not well enough to travel. Instead, he wrote his comrades a letter, closing with these words:

“Live free or die: Death is not the worst of evils.”

The name of the American Cincinnatus is all but forgotten today but his words live on, imprinted on every license plate, in the state of New Hampshire. “Live Free or Die”.

Raleigh believed that the Chesapeake afforded better opportunities for his new settlement, but Portuguese pilot Simon Fernandes, had other ideas. The caravan stopped at Roanoke Island in July, 1587, to check on the 15 men left behind a year earlier. Fernandes was a Privateer, impatient to resume his hunt for Spanish shipping. He ordered the colonists ashore on Roanoke Island.

Raleigh believed that the Chesapeake afforded better opportunities for his new settlement, but Portuguese pilot Simon Fernandes, had other ideas. The caravan stopped at Roanoke Island in July, 1587, to check on the 15 men left behind a year earlier. Fernandes was a Privateer, impatient to resume his hunt for Spanish shipping. He ordered the colonists ashore on Roanoke Island.

Photo credit to Mark Theissen with permission of Brenau University

Photo credit to Mark Theissen with permission of Brenau University Research concluded at “Site X” in 2017, the cloak & dagger moniker given to deter thieves and looters. The mystery of the lost Colony of Roanoke, remains unsolved. “We don’t know exactly what we’ve got here,” admitted one archaeologist. “It remains a bit of an enigma.”

Research concluded at “Site X” in 2017, the cloak & dagger moniker given to deter thieves and looters. The mystery of the lost Colony of Roanoke, remains unsolved. “We don’t know exactly what we’ve got here,” admitted one archaeologist. “It remains a bit of an enigma.”

Queen Elizabeth I of England granted Walter Raleigh a charter to establish a colony north of Spanish Florida in 1583, the area called “Virginia” in honor of the

Queen Elizabeth I of England granted Walter Raleigh a charter to establish a colony north of Spanish Florida in 1583, the area called “Virginia” in honor of the  Following the coastline, Gosnold discovered an island covered with wild grapes. Naming it after his deceased daughter, he called the place Martha’s Vineyard. The expedition came ashore on Cuttyhunk in the Elizabethan island chain where they briefly ran a trading post, before heading back to England. Today, Gosnold is the smallest town in Massachusetts with a population of 75 with most of the land owned by the Forbes family.

Following the coastline, Gosnold discovered an island covered with wild grapes. Naming it after his deceased daughter, he called the place Martha’s Vineyard. The expedition came ashore on Cuttyhunk in the Elizabethan island chain where they briefly ran a trading post, before heading back to England. Today, Gosnold is the smallest town in Massachusetts with a population of 75 with most of the land owned by the Forbes family.

The British warship HMS Nimrod fired on my little town during the War of 1812. It’s closed now, but the building formerly housing the Nimrod Restaurant, still sports a hole in the wall where the cannon ball came in.

The British warship HMS Nimrod fired on my little town during the War of 1812. It’s closed now, but the building formerly housing the Nimrod Restaurant, still sports a hole in the wall where the cannon ball came in.

The dredging of a canal connecting the Manomet and Scusset rivers and cutting 62 miles off the water route from Boston to New York had been talked about since the time of Miles Standish. Construction of a privately owned toll canal began on June 22, 1909. Giant boulders left by the glaciers and ghastly winter weather hampered construction, the canal finally opening on July 29, 1914 and charging a maximum of $16 per vessel. Navigation was difficult, due to a 5-plus mile-per-hour current combined with a maximum width of 100′ and a max. depth of 25-feet. Several accidents damaged the canal’s reputation and toll revenues failed to meet investors’ expectations.

The dredging of a canal connecting the Manomet and Scusset rivers and cutting 62 miles off the water route from Boston to New York had been talked about since the time of Miles Standish. Construction of a privately owned toll canal began on June 22, 1909. Giant boulders left by the glaciers and ghastly winter weather hampered construction, the canal finally opening on July 29, 1914 and charging a maximum of $16 per vessel. Navigation was difficult, due to a 5-plus mile-per-hour current combined with a maximum width of 100′ and a max. depth of 25-feet. Several accidents damaged the canal’s reputation and toll revenues failed to meet investors’ expectations. Despite the WuFlu, millions of tourists will wait countless hours this year in a sea of brake lights, to cross those two narrow roadways onto “the Cape” to enjoy that brief blessed moment of warmth hidden amidst our four seasons, known locally as “almost winter, winter, still winter and bridge construction”.

Despite the WuFlu, millions of tourists will wait countless hours this year in a sea of brake lights, to cross those two narrow roadways onto “the Cape” to enjoy that brief blessed moment of warmth hidden amidst our four seasons, known locally as “almost winter, winter, still winter and bridge construction”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.