The participants in this story have long since passed from among us. Every one. It is their countrymen who remember a debt of gratitude, one-hundred years in the making. For near-half a century, this has taken the form of a tree. A gift, from the people of Nova Scotia, to the people of Boston.

As “The Great War” dragged on to the end of its third year in Europe, Halifax harbor in Nova Scotia was the bustling scene of supply, munition, and troop ships destined for “over there”. With a population of 50,000 at the time, Halifax was the busiest port in Atlantic Canada.

The Norwegian vessel SS Imo slipped her moorings in Halifax harbor on the morning of December 6, destined for New York City. The French freighter Mont Blanc was entering the harbor at this time, intending to join the convoy which would form her North Atlantic escort. In her holds, Mont Blanc carried 200 tons of Trinitrotoluene (TNT), and 2,300 tons of TNP – Trinitrophenol or “Picric Acid”, a substance then in use as a high explosive.

In addition, the freighter carried 35 tons of high octane gasoline and 20,000 lbs of gun cotton. Not wanting to draw the attention of pro-German saboteurs, the freighter flew no flags warning of her cargo. Mont Blanc was a floating bomb.

Somehow, signals became crossed as the two ships passed, colliding in the narrows at the harbor entrance and igniting the TNP on board Mont Blanc. French sailors abandoned ship as fast as they could, warning everyone who would listen of what was about to happen.

Meanwhile, the spectacle of a flaming ship was too much to resist, as crowds gathered around the harbor. The high-pitched shriek emitted by picric acid under combustion is familiar to anyone who has ever attended a public fireworks display. You can only imagine the scene as the burning freighter brushed the harbor pier, setting that ablaze, before running aground.

The explosion and resulting fires killed over 1,800, flattening the north end of Halifax and shattering windows as far as fifty miles away. It was one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history, destroying over 1,600 homes on the cusp of a Canadian winter.

Mont Blanc’s half-ton anchor landed over two miles away, one of her gun barrels, three. Later analysis estimated an output of 2.9 kilotons, an explosive force greater than many tactical nuclear weapons.

The December 7 sun rose over a scene from the apocalypse, as a blizzard descended across Nova Scotia. Over 9,000 were injured, many gravely so, and not only homeless. Their whole town was gone.

Boston Mayor James Michael Curley wrote to the American Representative in Halifax “The city of Boston has stood first in every movement of similar character since 1822, and will not be found wanting in this instance. I am, awaiting Your Honor’s kind instruction.”

Curley was as good as his word. The Mayor and Massachusetts’ Governor Samuel McCall composed a Halifax Relief Committee to raise funds and organize aid. McCall reported the effort raised $100,000 in its first hour alone, equivalent to over $1.9 million, today.

Curley was as good as his word. The Mayor and Massachusetts’ Governor Samuel McCall composed a Halifax Relief Committee to raise funds and organize aid. McCall reported the effort raised $100,000 in its first hour alone, equivalent to over $1.9 million, today.

President Woodrow Wilson authorized a $30,000 carload of Army blankets sent to Halifax. Within twelve hours of the explosion, the Boston Globe reported on the first train leaving North Station, with “30 of Boston’s leading physicians and surgeons, 70 nurses, a completely equipped 500-bed base hospital unit and a vast amount of hospital supplies”.

Delayed by deep snow drifts, the train arrived on the morning of December 8, the first non-Canadian relief train, on the scene.

$750,000 in relief aid would arrive from Massachusetts alone, equivalent to more than $15 million today. Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden would write to Governor McCall on December 9, “On behalf of the Government of Canada, I desire to convey to Your Excellency our very sincere and warm thanks for your sympathy and aid in the appalling calamity which has befallen Halifax”.

The following year, Nova Scotia sent the city of Boston a gift of gratitude. A very large Christmas tree.

In 1971, the Lunenburg County Christmas Tree Producers Association sent another tree to Boston, both to promote Christmas tree exports, and to once again acknowledge the support of the people and government of Boston, following the 1917 disaster. The Nova Scotia government later took over the annual gift of the Christmas tree, to promote trade and tourism.

So it is that, every year, the people of Nova Scotia send the people of Boston the official Christmas tree, to be displayed on Boston Common. The tree even has its own Facebook page. More recently, the principle tree is joined by two smaller ones, donated to Rosie’s Place and the Pine Street Inn, two of Boston’s homeless shelters.

The 2018 tree begins the 600-mile journey south

This is no Charlie Brown shrub we’re talking about. The 1998 tree required 3,200 man-hours to decorate, with 17,000 lights connected by 4½ miles of wire and bedecked with 8,000 bulbs.

In 2013, the tree was accompanied by a group of runners, in recognition of the Boston Marathon bombing in April of that year.

The 2018 tree is a white spruce standing 46-feet, for the first time selected from the Cumberland County town of Oxford, and donated by Ross McKellar and Teresa Simpson. It takes two men a day and a half to prepare for cutting, a crane holding the tree upright while the chainsaw does its work. It’s a major media event as the tree is paraded through Halifax on a 53’ flatbed trailer, before beginning the 600-mile journey south.

For a small Canadian province, it’s been no small commitment. In 2016 Nova Scotia spent $242,000 on the program, including transportation, cutting & lighting ceremonies, and all the promotions which went with it. The government of the province, says the program is well worth the expense.

“This is about friendship, unity and gratitude to the people of Boston,” said Deputy Premier Karen Casey on behalf of Premier Stephen McNeil. “We are forever appreciative of Boston’s immediate response of aid after the explosion. This tree embodies the spirit of our culture and is our way of saying thank you.”

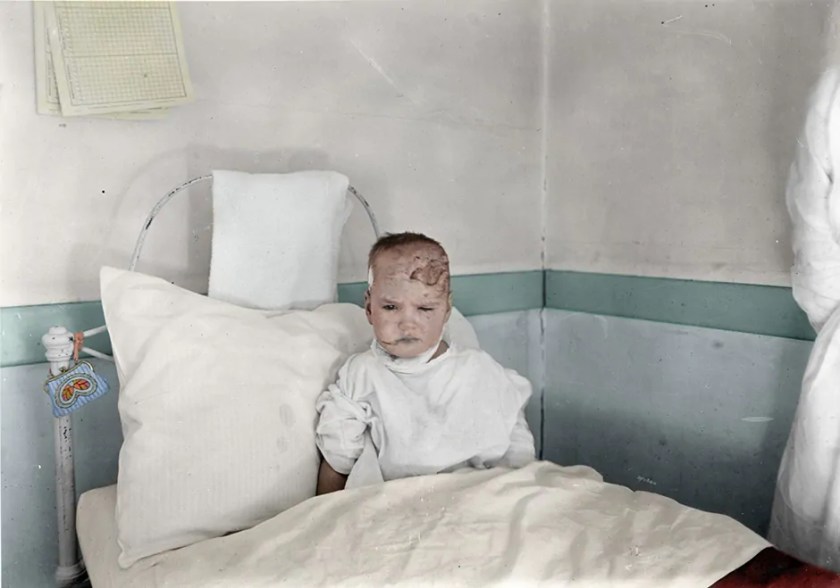

Feature image, top of page: This colorized photo only hints at the scale of the disaster. Hat tip, CBC

If you enjoyed this “Today in History”, please feel free to re-blog, “like” & share on social media, so that others may find and enjoy it as well. Please click the “follow” button on the right, to receive email updates on new articles. Thank you for your interest, in the history we all share.

There was strong sentiment at the time, that German sabotage lay behind the disaster. A front-page headline on the December 10 Halifax Herald Newspaper proclaimed “Practically All the Germans in Halifax Are to Be Arrested”.

There was strong sentiment at the time, that German sabotage lay behind the disaster. A front-page headline on the December 10 Halifax Herald Newspaper proclaimed “Practically All the Germans in Halifax Are to Be Arrested”.

This is no Charlie Brown shrub we’re talking about. The 1998 tree required 3,200 man-hours to decorate: 17,000 lights connected by 4½ miles of wire, and decorated with 8,000 bulbs.

This is no Charlie Brown shrub we’re talking about. The 1998 tree required 3,200 man-hours to decorate: 17,000 lights connected by 4½ miles of wire, and decorated with 8,000 bulbs.

You must be logged in to post a comment.