In the early days of the American Revolution, the 2nd Continental Congress looked north, to the Province of Quebec. The region was lightly defended at the time, and Congress was alarmed at its potential as a British base from which to attack and divide the colonies.

The Continental army’s expedition to Quebec ended in disaster on December 31, as General Benedict Arnold was severely injured with a bullet wound to his left leg. Major General Richard Montgomery was killed and Colonel Daniel Morgan was captured, along with about 400 fellow patriots.

Quebec was massively reinforced in the Spring of 1776, with the arrival of 10,000 British and Hessian soldiers. By June, the remnants of the Continental army had been driven south to Fort Ticonderoga and Fort Crown Point.

Congress was right about the British intent to split the colonies. General Sir Guy Carleton, provincial governor of Quebec, set about doing so almost immediately.

Retreating colonials took with them or destroyed almost every boat along the way, capturing and arming four vessels in 1775: the Liberty, Enterprise, Royal Savage, and Revenge. Determined to take back the crucial waterway, the British set about disassembling warships along the St. Lawrence, moving them overland to Fort Saint-Jean on the uppermost navigable waters leading to Lake Champlain, the 125-mile long lake dividing upstate New York from Vermont.

There they spent the summer and early fall of 1776, literally building a fleet of warships along the upper reaches of the lake. 120 miles to their south, colonials were doing the same.

The Americans had a small fleet of shallow draft bateaux used for lake transport, but needed something larger and heavier to sustain naval combat.

In 1759, British Army Captain Philip Skene founded a settlement on the New York side of Lake Champlain, built around saw mills, grist mills, and an iron foundry.

Today, the former village of Skenesborough is known as “Whitehall”, considered by many to be the birthplace of the United States Navy. In 1776, Major General Horatio Gates put the American ship building operation into motion on the banks of Skenesborough Harbor.

Hermanus Schuyler oversaw the effort, while military engineer Jeduthan Baldwin was in charge of outfitting. Gates asked General Benedict Arnold, an experienced ship’s captain, to spearhead the effort, explaining “I am intirely uninform’d as to Marine Affairs”.

200 carpenters and shipwrights were recruited to the wilderness of upstate New York. So inhospitable was this duty that workmen were paid more than anyone else in the Navy, with the sole exception of Commodore Esek Hopkins. Meanwhile, foraging parties scoured the countryside looking for guns, knowing that there was going to be a fight on Lake Champlain.

It is not widely known, that the American Revolution was fought in the midst of a smallpox pandemic. General George Washington was an early proponent of vaccination, an untold benefit to the American war effort. Nevertheless, a fever broke out among the shipbuilders of Skenesborough, that almost brought their work to a halt.

It was a hastily built and in some cases incomplete fleet that slipped into the water in the summer and autumn of 1776. In just over two months, the American shipbuilding effort produced eight 54′ gondolas (gunboats), and four 72′ galleys. Upon completion, each hull was rowed to Fort Ticonderoga, where it was fitted with masts, rigging, guns, and supplies. By October 1776, the American fleet numbered 16 vessels, determined to stop the British fleet heading south.

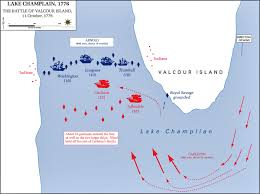

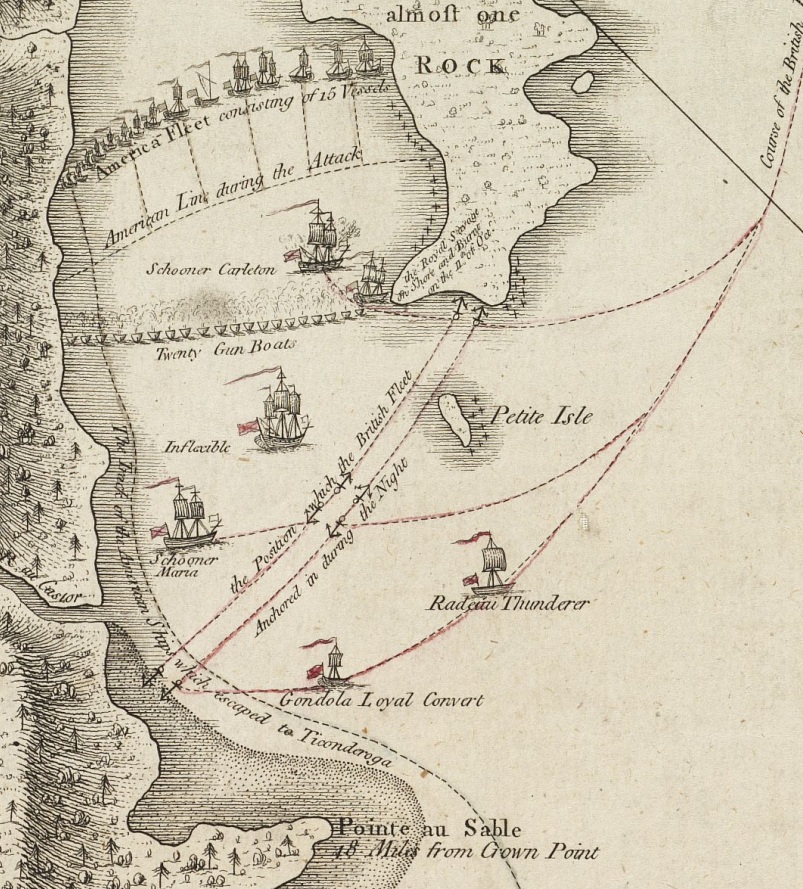

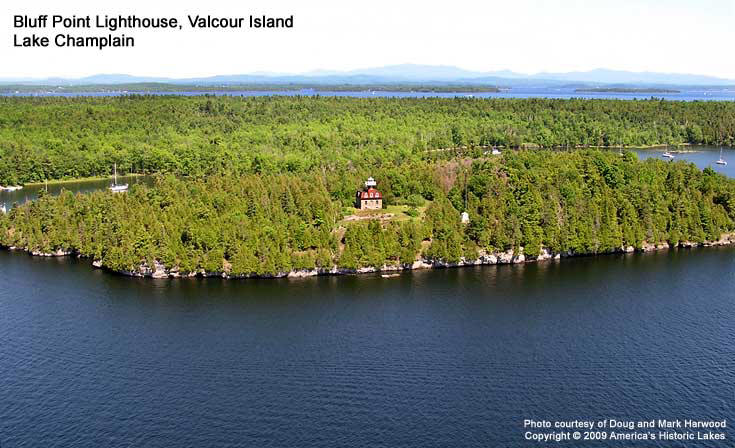

As the two sides closed in the early days of October, General Arnold knew he was at a disadvantage. The element of surprise was going to be critical. Arnold chose a small strait to the west of Valcour Island, where he was hidden from the main part of the lake. There he drew his small fleet into a crescent formation, and waited.

Carleton’s fleet, commanded by Captain Thomas Pringle, entered the northern end of Lake Champlain on October 9.

Sailing south on the 11th under favorable winds, some of the British ships had already passed the American position behind Valcour island, before realizing they were there. Some of the British warships were able to turn and give battle, but the largest ones were unable to turn into the wind.

Sailing south on the 11th under favorable winds, some of the British ships had already passed the American position behind Valcour island, before realizing they were there. Some of the British warships were able to turn and give battle, but the largest ones were unable to turn into the wind.

Fighting continued for several hours until dark, and both sides did some damage. On the American side, Royal Savage ran aground and burned. The gondola Philadelphia was sunk. On the British side, one gunboat blew up. The two sides lost about 60 men, each. In the end, the larger ships and the more experienced seamanship of the English, made it an uneven fight.

Only a third of the British fleet was engaged that day, but the battle went badly for the Patriot side. That night, the battered remnants of the American fleet slipped through a gap in the lines, limping down the lake on muffled oars. British commanders were surprised to find them gone the next morning, and gave chase.

One vessel after another was overtaken and destroyed on the 12th, or else, too damaged to go on, was abandoned. The cutter Lee was run aground by its crew, who then escaped through the woods. Four of sixteen American vessels escaped north to Ticonderoga, only to be captured or destroyed by British forces, the following year.

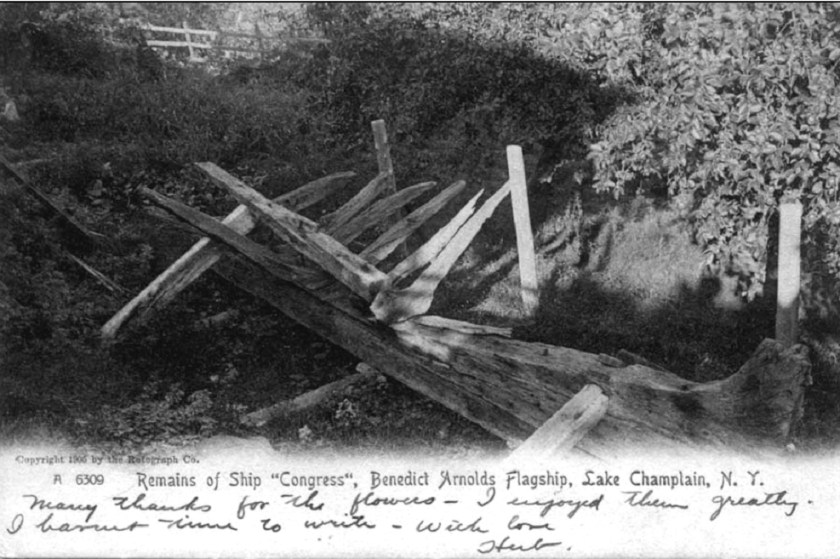

On the third day, the last four gunboats and Benedict Arnold’s flagship Congress were run aground in Ferris Bay on the Vermont side, following a 2½-hour running gun battle. Today, the small harbor is called Arnold’s Bay.

On the third day, the last four gunboats and Benedict Arnold’s flagship Congress were run aground in Ferris Bay on the Vermont side, following a 2½-hour running gun battle. Today, the small harbor is called Arnold’s Bay.

200 escaped to shore, the last of whom was Benedict Arnold himself, personally torching his own flagship before leaving it for the last time, flag still flying.

The British would retain control of Lake Champlain, through the end of the war.

The American fleet never had a chance and everyone knew it. Yet it had been able to inflict enough damage at a point late enough in the year, that Carlton’s fleet was left with no choice but to return north for the winter. One day, Benedict Arnold would enter history as a traitor to his country. For now, the General had bought his young nation, another year in which to fight.

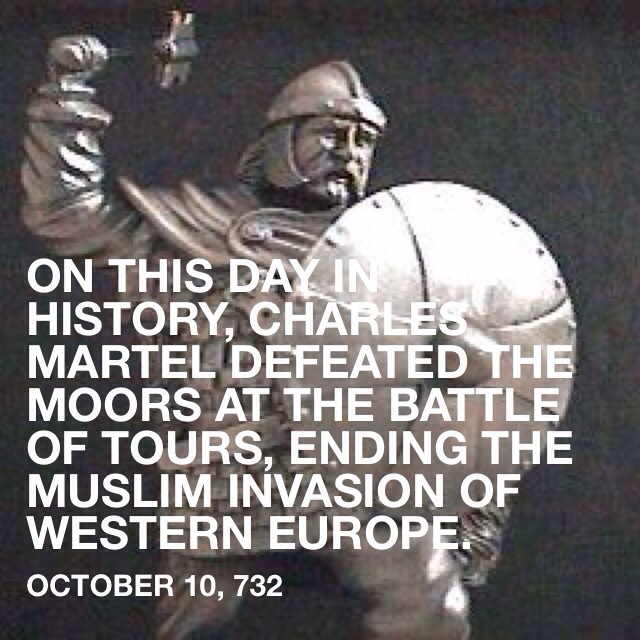

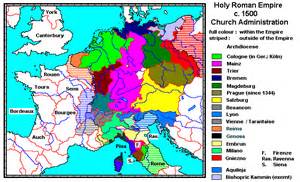

Charlemagne led an incursion into Muslim Spain, continuing his father’s policy toward the Church when he cleared the Lombards out of Northern Italy. He Christianized the Saxon tribes to his east, sometimes under pain of death.

Charlemagne led an incursion into Muslim Spain, continuing his father’s policy toward the Church when he cleared the Lombards out of Northern Italy. He Christianized the Saxon tribes to his east, sometimes under pain of death.

The diary tells of a respect this man had for “Captain Boeing”. Beaten almost senseless, his arms tied so tightly that his elbows touched behind his back, Captain Pease was driven to his knees in the last moments of his life. Knowing he was about to die, Harl Pease uttered the most searing insult possible against an expert swordsman and self-styled “samurai”. Particularly one with such a helpless victim. It was the single word, in Japanese. “Once!“.

The diary tells of a respect this man had for “Captain Boeing”. Beaten almost senseless, his arms tied so tightly that his elbows touched behind his back, Captain Pease was driven to his knees in the last moments of his life. Knowing he was about to die, Harl Pease uttered the most searing insult possible against an expert swordsman and self-styled “samurai”. Particularly one with such a helpless victim. It was the single word, in Japanese. “Once!“.

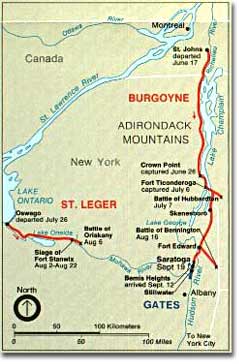

American forces selected a site called Bemis Heights, about 10 miles south of Saratoga, spending a week constructing defensive works with the help of Polish engineer Thaddeus Kosciusko. It was a formidable position: mutually supporting cannon on overlapping ridges, with interlocking fields of fire. Burgoyne knew he had no choice but to stop and give battle at the American position, or be chopped to pieces trying to bypass it.

American forces selected a site called Bemis Heights, about 10 miles south of Saratoga, spending a week constructing defensive works with the help of Polish engineer Thaddeus Kosciusko. It was a formidable position: mutually supporting cannon on overlapping ridges, with interlocking fields of fire. Burgoyne knew he had no choice but to stop and give battle at the American position, or be chopped to pieces trying to bypass it. The second and decisive battle for Saratoga, the Battle of Bemis Heights, occurred on October 7, 1777.

The second and decisive battle for Saratoga, the Battle of Bemis Heights, occurred on October 7, 1777.

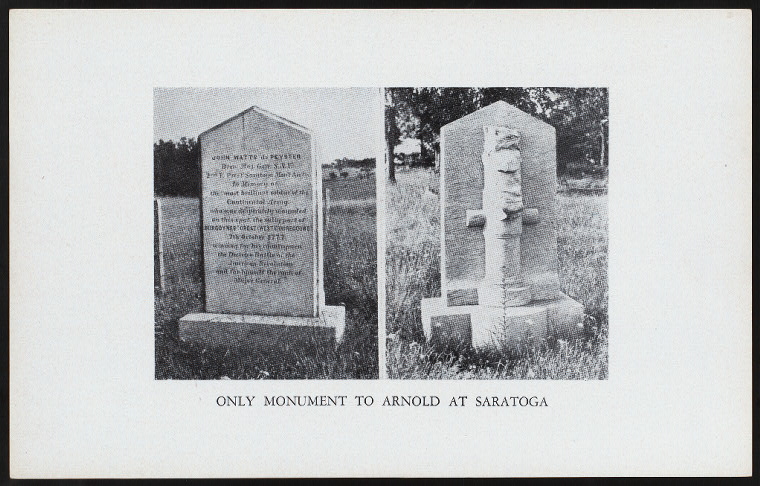

Today, the Saratoga battlefield and the site of Burgoyne’s surrender are preserved as the Saratoga National Historical Park. On the grounds of the park stands an obelisk, containing four niches.

Today, the Saratoga battlefield and the site of Burgoyne’s surrender are preserved as the Saratoga National Historical Park. On the grounds of the park stands an obelisk, containing four niches.

It was game four of the World Series between the Cubbies and the Detroit Tigers, October 6, 1945, with Chicago home at Wrigley Field. Billy Sianis, owner of the Billy Goat Tavern in Chicago, bought tickets for himself and his pet goat “Murphy”. Anyone who’s ever found himself in the company of a goat understands the problem. Right?

It was game four of the World Series between the Cubbies and the Detroit Tigers, October 6, 1945, with Chicago home at Wrigley Field. Billy Sianis, owner of the Billy Goat Tavern in Chicago, bought tickets for himself and his pet goat “Murphy”. Anyone who’s ever found himself in the company of a goat understands the problem. Right? Billy Sianis was right. The Cubs were up two games to one at the time, but they went on to lose the series. They’ve been losing ever since.

Billy Sianis was right. The Cubs were up two games to one at the time, but they went on to lose the series. They’ve been losing ever since. Alou slammed his glove down in anger and frustration. Pitcher Mark Prior glared at the stands, crying “fan interference”. The Marlins came back with 8 unanswered runs in the inning. Steve Bartman required a police escort to get out of the field alive.

Alou slammed his glove down in anger and frustration. Pitcher Mark Prior glared at the stands, crying “fan interference”. The Marlins came back with 8 unanswered runs in the inning. Steve Bartman required a police escort to get out of the field alive.

The mother of all droughts came to a halt on November 2 in a ten-inning cardiac arrest that had us all up Way past midnight, on a school night. I even watched that 17-minute rain delay, and I’m a Red Sox guy.

The mother of all droughts came to a halt on November 2 in a ten-inning cardiac arrest that had us all up Way past midnight, on a school night. I even watched that 17-minute rain delay, and I’m a Red Sox guy.

The family settled for a time in Hannover, West Germany, barely avoiding the communist noose as it closed around their former home in the East.

The family settled for a time in Hannover, West Germany, barely avoiding the communist noose as it closed around their former home in the East.

Steppenwolf gave us 22 albums. We all know them in one way or another. Yet, the lead singer’s escape from the horrors of the Iron Curtain, not once but twice, is all but unknown. That, as Paul Harvey used to say, is the Rest, of the Story.

Steppenwolf gave us 22 albums. We all know them in one way or another. Yet, the lead singer’s escape from the horrors of the Iron Curtain, not once but twice, is all but unknown. That, as Paul Harvey used to say, is the Rest, of the Story.

Once, the small dog was able to perform a task in minutes that otherwise would have taken an airstrip out of service for three days, and exposed an entire construction battalion to enemy fire. The air field at Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, was crucial to the Allied war effort, and the signal corps needed to run a telegraph wire across the field. A 70′ long, 8” pipe crossed underneath the air strip, half filled with dirt.

Once, the small dog was able to perform a task in minutes that otherwise would have taken an airstrip out of service for three days, and exposed an entire construction battalion to enemy fire. The air field at Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, was crucial to the Allied war effort, and the signal corps needed to run a telegraph wire across the field. A 70′ long, 8” pipe crossed underneath the air strip, half filled with dirt. Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and entertaining thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s considered to be the first therapy dog, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed.

Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and entertaining thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s considered to be the first therapy dog, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed. Bill Wynne was 90 years old in 2012, when he was “flabbergasted” to be approached by Australian authorities. They explained that an Australian army nurse had purchased the dog from a Queen Street pet store, becoming separated in the jungles of New Guinea. 68 years later, the Australians had come to award his dog a medal.

Bill Wynne was 90 years old in 2012, when he was “flabbergasted” to be approached by Australian authorities. They explained that an Australian army nurse had purchased the dog from a Queen Street pet store, becoming separated in the jungles of New Guinea. 68 years later, the Australians had come to award his dog a medal.

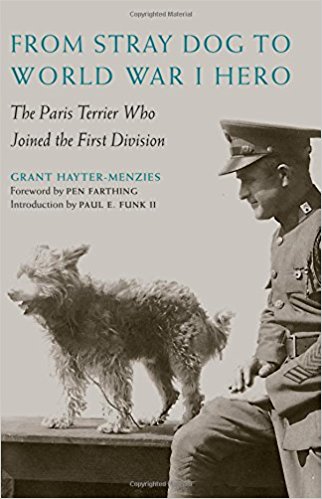

It was a small dog, possibly a Cairn Terrier mix. He looked like a pile of rags, and that’s what they called him. The dog had gotten Donovan out of a jam, now he would become the division mascot for real. Rags was now part of the US 1st Infantry Division, the Big Red One.

It was a small dog, possibly a Cairn Terrier mix. He looked like a pile of rags, and that’s what they called him. The dog had gotten Donovan out of a jam, now he would become the division mascot for real. Rags was now part of the US 1st Infantry Division, the Big Red One.

You must be logged in to post a comment.