During the twentieth century, the United States and others specially recruited bilingual speakers of obscure languages, then applying those skills in secret communications based on those languages. Among these, the story of the Navajo “Code Talkers” are probably best known. Theirs was a language with no alphabet or symbols, a language with such complex syntax and tonal qualities as to be unintelligible to the non-speaker. The military code based on such a language proved unbreakable in WWII. Japanese code breakers never got close.

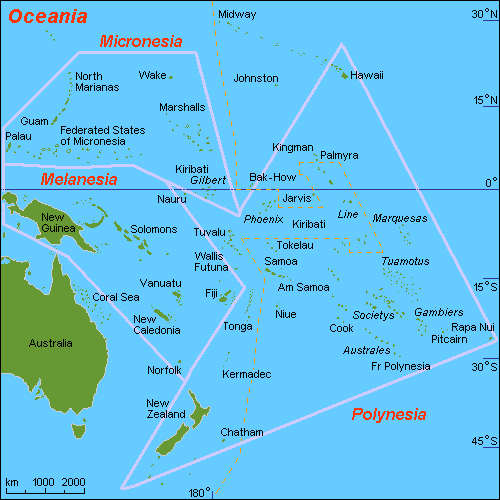

The United States Marine Corps recruited some 4-500 Navajo speakers, who served in all six Marine divisions in the Pacific theater. Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Peleliu, Iwo Jima: Navajo code talkers took part in every assault conducted by the United States Marine Corps, from 1942 to ‘45.

The history of the Navajo code talkers of WWII is relatively well known, but by no means, unique. Indigenous Americans of other nations served as code talkers in WW2, including Assiniboine, Lakota and Meskwaki soldiers, who did service in the Pacific, North African, and European theaters of the war.

The history of the Navajo code talkers of WWII is relatively well known, but by no means, unique. Indigenous Americans of other nations served as code talkers in WW2, including Assiniboine, Lakota and Meskwaki soldiers, who did service in the Pacific, North African, and European theaters of the war.

Fourteen Comanche soldiers took part in the Normandy landings. As with the Navajo, these substituted phrases when their own language lacked a proper term. Thus, “tank” became “turtle”. “Bombers” became “pregnant airplanes”. Adolf Hitler was “Crazy White Man”.

The information is contradictory, but Basque may also have been put to use, in areas where no native speakers were believed to be present. Native Cree speakers served with Canadian Armed Services, though oaths of secrecy have all but blotted their contributions, from the pages of history.

The first documented use of military codes based on native American languages took place during the Second Battle of the Somme in September of 1918, employing on the language skills of a number of Cherokee troops.

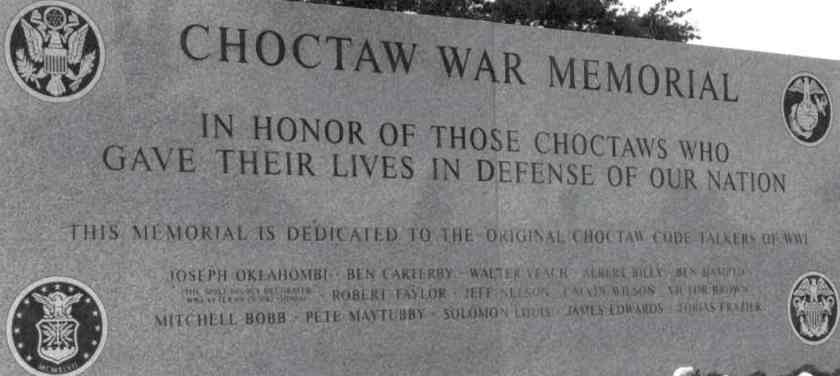

The government of Choctaw nation will tell you otherwise, contending that Theirs was the first native language, used in this way. Late in 1917, Colonel Alfred Wainwright Bloor was serving in France with the 142nd Infantry Regiment. They were a Texas outfit, constituted in May of that year and including a number of Oklahoma Choctaws.

The Allies had already learned the hard way that their German adversaries spoke excellent English, and had already intercepted and broken several English-based codes. Colonel Bloor heard two of his Choctaw soldiers talking to each other, and realized he didn’t have the foggiest notion of what they were saying. If he didn’t understand their conversation, the Germans wouldn’t have a clue.

The first test under combat conditions took place on October 26, 1918, as two companies of the 2nd Battalion performed a “delicate” withdrawal from Chufilly to Chardeny, in the Champagne sector. A captured German officer later confirmed the Choctaw code to have been a complete success. We were “completely confused by the Indian language”, he said, “and gained no benefit whatsoever” from wiretaps.

Choctaw soldiers were placed in multiple companies of infantry. Messages were transmitted via telephone, radio and by runner, many of whom were themselves native Americans.

As in the next war, Choctaw would improvise when their language lacked the proper word or phrase. When describing artillery, they used the words for “big gun”. Machine guns were “little gun shoot fast”.

The Choctaw themselves didn’t use the term “Code Talker”, that wouldn’t come along until WWII. At least one member of the group, Tobias W. Frazier, simply described what they did as, “talking on the radio”. Of the 19 who served in WWI, 18 were native Choctaw from southeast Oklahoma. The last was a native Chickasaw. The youngest was Benjamin Franklin Colbert, Jr., the son of Benjamin Colbert Sr., one of Teddy Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders” of the Spanish American War. Born September 15, 1900 in the Durant Indian Territory, he was all of sixteen, the day he enlisted.

The Choctaw themselves didn’t use the term “Code Talker”, that wouldn’t come along until WWII. At least one member of the group, Tobias W. Frazier, simply described what they did as, “talking on the radio”. Of the 19 who served in WWI, 18 were native Choctaw from southeast Oklahoma. The last was a native Chickasaw. The youngest was Benjamin Franklin Colbert, Jr., the son of Benjamin Colbert Sr., one of Teddy Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders” of the Spanish American War. Born September 15, 1900 in the Durant Indian Territory, he was all of sixteen, the day he enlisted.

Another was Choctaw Joseph Oklahombi, whose name means “man killer” in the Choctaw language. Six days before Sergeant York’s famous capture of 132 Germans in the Argonne Forest, Joseph Oklahombi charged a strongly held German position, single-handed. Oklahombi‘s Croix de Guerre citation, personally awarded him by Marshall Petain, tells the story:

“Under a violent barrage, [Pvt. Oklahombi] dashed to the attack of an enemy position, covering about 210 yards through barbed-wire entanglements. He rushed on machine-gun nests, capturing 171 prisoners. He stormed a strongly held position containing more than 50 machine guns, and a number of trench mortars. Turned the captured guns on the enemy, and held the position for four days, in spite of a constant barrage of large projectiles and of gas shells. Crossed no man’s land many times to get information concerning the enemy, and to assist his wounded comrades”.

Unconfirmed eyewitness accounts report that 250 Germans occupied the position, and that Oklahombi killed 79 of them before their comrades decided it was wiser to surrender. Some guys are not to be trifled with.

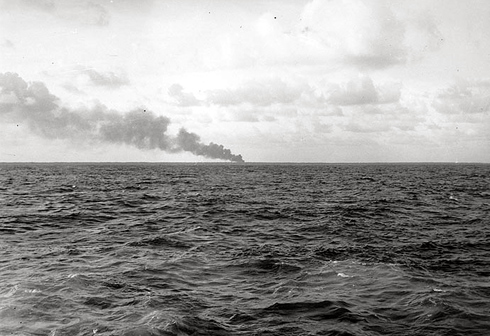

The harbor at Scapa flow had been home to the British deep water fleet since 1904, a time when the place truly was, all but impregnable. By 1939, anti-aircraft weaponry was all but obsolete, old block ships were disintegrating, and anti-submarine nets were inadequate to the needs of the new war.

The harbor at Scapa flow had been home to the British deep water fleet since 1904, a time when the place truly was, all but impregnable. By 1939, anti-aircraft weaponry was all but obsolete, old block ships were disintegrating, and anti-submarine nets were inadequate to the needs of the new war. The electric torpedoes of the era were highly unreliable, and this wasn’t shaping up to be their night.

The electric torpedoes of the era were highly unreliable, and this wasn’t shaping up to be their night.

The European allies and Imperial Germany had about 20,000 dogs working a variety of jobs in WWI. Though the United States didn’t have an official “War Dog” program in those days, a Staffordshire Terrier mix called “Sgt. Stubby” was smuggled “over there” with an AEF unit training out of New Haven, Connecticut.

The European allies and Imperial Germany had about 20,000 dogs working a variety of jobs in WWI. Though the United States didn’t have an official “War Dog” program in those days, a Staffordshire Terrier mix called “Sgt. Stubby” was smuggled “over there” with an AEF unit training out of New Haven, Connecticut.

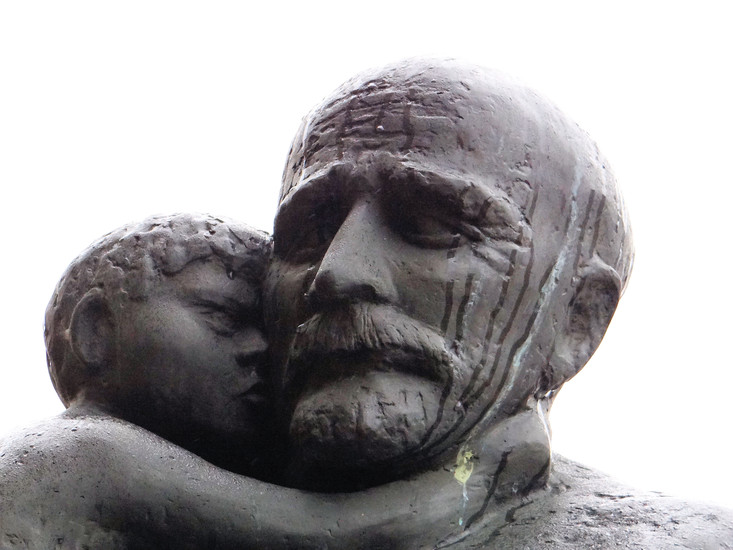

Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and licking faces & performing tricks for thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s been called “the first published post-traumatic stress canine”, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed.

Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and licking faces & performing tricks for thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s been called “the first published post-traumatic stress canine”, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed. A memorial statue was unveiled on December 12 of that year, at the Australian War Memorial at the Queensland Wacol Animal Care Campus in Brisbane.

A memorial statue was unveiled on December 12 of that year, at the Australian War Memorial at the Queensland Wacol Animal Care Campus in Brisbane.

Early armored cars were fine for moving personnel over smooth roads, but there was a need for a vehicle capable of navigating the broken terrain of no man’s land. In the run-up to WWI, several soon-to-be belligerents were conducting experiments with “land ships”, with varying degrees of success.

Early armored cars were fine for moving personnel over smooth roads, but there was a need for a vehicle capable of navigating the broken terrain of no man’s land. In the run-up to WWI, several soon-to-be belligerents were conducting experiments with “land ships”, with varying degrees of success.

The most unusual tank of WWI was the tricycle designed “Lebedenko” or “Tsar Tank”. Developed by pre-Soviet Russia, the armament and crew quarters on this thing were 27′ from the ground, making them irresistible targets for enemy artillery.

The most unusual tank of WWI was the tricycle designed “Lebedenko” or “Tsar Tank”. Developed by pre-Soviet Russia, the armament and crew quarters on this thing were 27′ from the ground, making them irresistible targets for enemy artillery.

Interior temperatures rose to 122° Fahrenheit and more, making me wonder if these things weren’t as dangerous to their own crews as they were to the other side.

Interior temperatures rose to 122° Fahrenheit and more, making me wonder if these things weren’t as dangerous to their own crews as they were to the other side.

The only German project to be produced and fielded in WWI was the A7V. They only made 20 of these things in the armored, “Sturmpanzerwagen Oberschlesien“, “Upper Silesia Assault Armored Vehicle” version, and a few more in the unarmored “Überlandwagen”, “Over-land vehicle”, used for cargo transport.

The only German project to be produced and fielded in WWI was the A7V. They only made 20 of these things in the armored, “Sturmpanzerwagen Oberschlesien“, “Upper Silesia Assault Armored Vehicle” version, and a few more in the unarmored “Überlandwagen”, “Over-land vehicle”, used for cargo transport. It would be very different, in the next war.

It would be very different, in the next war.

John Connell Freeborn was a pilot with the RAF, and a good one, too. Credited with 13½ enemy aircraft shot down, Freeborn flew more operational hours during the Battle of Britain, than any other pilot, ending the war with a Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar, and completing his RAF career as a Wing Commander. Yet, there is a time when every hero is as green as the grass. In the beginning, John Freeborn like everyone else, were rank amateurs.

John Connell Freeborn was a pilot with the RAF, and a good one, too. Credited with 13½ enemy aircraft shot down, Freeborn flew more operational hours during the Battle of Britain, than any other pilot, ending the war with a Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar, and completing his RAF career as a Wing Commander. Yet, there is a time when every hero is as green as the grass. In the beginning, John Freeborn like everyone else, were rank amateurs.

Richard Hough and Denis Richards wrote about the episode in

Richard Hough and Denis Richards wrote about the episode in

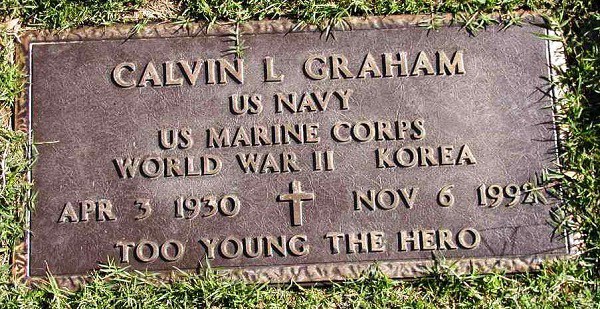

Being around newspapers allowed the boy to keep up on events overseas, “I didn’t like Hitler to start with“, he once told a reporter. By age eleven, some of Graham’s cousins had been killed in the war, and the boy wanted to fight.

Being around newspapers allowed the boy to keep up on events overseas, “I didn’t like Hitler to start with“, he once told a reporter. By age eleven, some of Graham’s cousins had been killed in the war, and the boy wanted to fight.

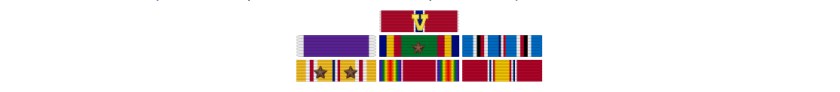

For the rest of his life, Calvin Graham fought for a clean service record, and for restoration of medical benefits. President Jimmy Carter personally approved an honorable discharge in 1978, and all Graham’s medals were reinstated, save for his Purple Heart. He was awarded $337 in back pay but denied medical benefits, save for the disability status conferred by the loss of one of his teeth, back in WW2.

For the rest of his life, Calvin Graham fought for a clean service record, and for restoration of medical benefits. President Jimmy Carter personally approved an honorable discharge in 1978, and all Graham’s medals were reinstated, save for his Purple Heart. He was awarded $337 in back pay but denied medical benefits, save for the disability status conferred by the loss of one of his teeth, back in WW2.

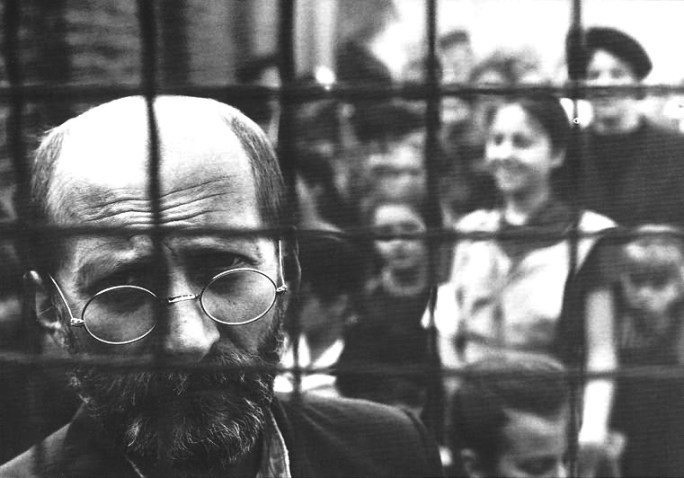

Born Henryk Goldszmit into the Warsaw family of Józef Goldszmit, in 1878 or ’79 (the sources vary), Korczak was the pen name by which he wrote children’s books.

Born Henryk Goldszmit into the Warsaw family of Józef Goldszmit, in 1878 or ’79 (the sources vary), Korczak was the pen name by which he wrote children’s books. Korczak wrote for several Polish language newspapers while studying medicine at the University of Warsaw, becoming a pediatrician in 1904. Always the writer, Korczak received literary recognition in 1905 with his book Child of the Drawing Room (Dziecko salonu), while serving as medical officer during the Russo-Japanese war.

Korczak wrote for several Polish language newspapers while studying medicine at the University of Warsaw, becoming a pediatrician in 1904. Always the writer, Korczak received literary recognition in 1905 with his book Child of the Drawing Room (Dziecko salonu), while serving as medical officer during the Russo-Japanese war.

The Polish nation, the sixth largest in all Europe, was sectioned and partitioned for over a century, by Austrian, Prussian, and Russian imperial powers. Korczak volunteered for military service in 1914, serving as military doctor during WW1 and the series of Polish border wars between 1919-’21.

The Polish nation, the sixth largest in all Europe, was sectioned and partitioned for over a century, by Austrian, Prussian, and Russian imperial powers. Korczak volunteered for military service in 1914, serving as military doctor during WW1 and the series of Polish border wars between 1919-’21.

You must be logged in to post a comment.