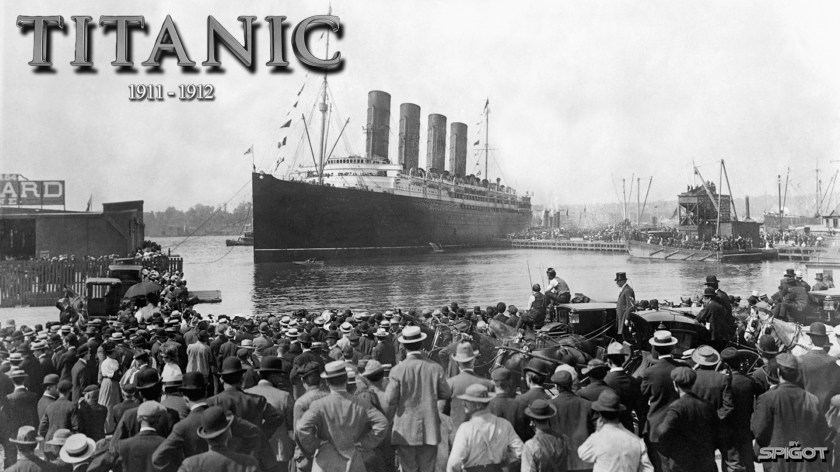

The maiden voyage of the largest ship afloat left the port of Southampton, England on April 10, 1912, carrying 2,224 passengers and crew. An accident was narrowly averted only minutes later, as Titanic passed the moored liners SS City of New York and Oceanic.

Both smaller ships lifted in the bow wave formed by Titanic’s passing, then dropped into the trough. New York’s mooring cables snapped, swinging her about, stern-first. Collision was averted by a bare 4-feet as the panicked crew of the tugboat Vulcan struggled to bring New York under tow.

By the evening of the 14th, Titanic was 400 miles off the coast of Newfoundland, conditions clear, calm and cold. There were warnings of drifting ice from other ships in the area, but it was generally believed that ice posed little danger to large vessels at this time. Captain Edward Smith opined that he “[couldn’t] imagine any condition which would cause a ship to founder. Modern shipbuilding has gone beyond that.”

Lookout Frederick Fleet alerted the bridge of an iceberg dead ahead at 11:40pm. First Officer William Murdoch ordered the engines put in reverse, veering the ship to the left. Lookouts were relieved, thinking that collision had been averted. Below the surface, the starboard side of Titanic ground into the iceberg, opening a gash the length of a football field.

The ship was built to survive flooding in four watertight compartments. The iceberg had opened five. As Titanic began to lower at the bow, it soon became clear that the ship was doomed.

The ship was built to survive flooding in four watertight compartments. The iceberg had opened five. As Titanic began to lower at the bow, it soon became clear that the ship was doomed.

Those aboard were poorly prepared for such an emergency. The ship was built for 64 wooden lifeboats, enough for 4,000, however the White Star Liner carried only 16 wooden lifeboats and four collapsibles. Regulations then in effect required enough room for 990 people. Titanic carried enough to accommodate 1,178.

As it was, there was room for over half of those on board, provided that each boat was filled to capacity. So strictly did Royal Navy officer Charles Lightoller adhere to the “women and children first” directive, that many boats were launched, half-full. The first lifeboat in the water, rated at 65 passengers, launched with only 28 aboard.

Lightoller himself survived, only by clinging to the bottom of an overturned raft.

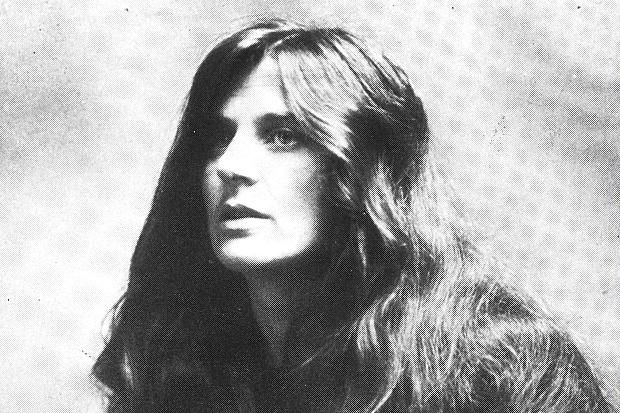

Violet Jessop was among those first to leave, clutching someone’s forgotten baby. As ship’s nurse, she was there to look after the comfort of the White Star Line passengers. Now, this small boat full of confused and disoriented women were being lowered into the cold and darkness of night, while all aboard the great ship was light, and warmth.

Denial is a funny thing, that psychological defense mechanism described by Sigmund Freud, in which a person rejects a plain fact too uncomfortable to contemplate. There was denial aplenty that night, from the well dressed passengers filing onto the decks, and from Violet Jessop, counting the lighted portholes as the boat creaked ever downward. One row, then two: every abandoned stateroom a tableau. Three, and four: feathered hats on dressers, scattered jewels on table tops. Five and then six: each lighted circle revealing a snapshot, soon to slip out of sight.

Floating on the still, frigid waters of the north Atlantic, Jessop must have wondered about Captain Smith. This was not their first cruise together, nor even their first shipwreck.

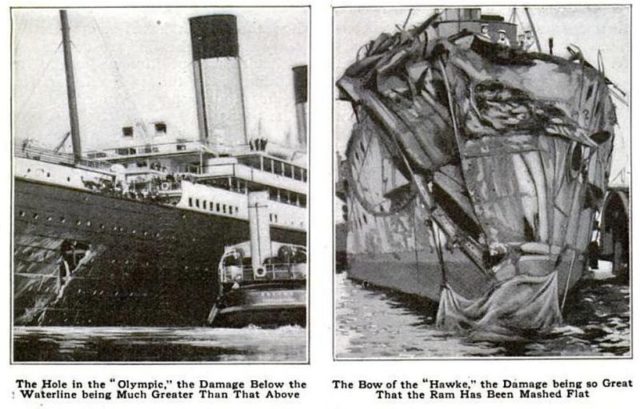

The White Star Line’s RMS Olympic set sail for New York seven months earlier, with Captain Edward Smith, commanding. Violet Jessop was on duty as the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Hawke performed mechanical tests, on a course parallel to the trans-Atlantic liner. Something went wrong and the tiller froze, swinging the bow of the Edgar-class cruiser, toward the liner. Hydrodynamic forces took over and the two ships collided, just after noon. The hull of the cruiser was smashed, two great gashes carved into the side of Olympic, one below the water line.

Two compartments flooded, but the watertight doors did their job. Olympic limped back to Southampton for repairs. Captain Smith and Violet Jessop moved on to the maiden voyage of her sister ship, the unsinkable RMS Titanic.

Denial turned to horror that frigid April night in 1912, when six rows of lights became five and then four, and Titanic began to rise by the stern. RMS Carpathia arrived on the scene around 4am in response to distress calls, and diverted to New York with survivors. Four days later, a crowd of 40,000 awaited the arrival of 705 survivors , in spite of a cold, driving rain. It would take four full days to compile and release the list of casualties.

Violet Jessop survived that night. Captain Smith, did not.

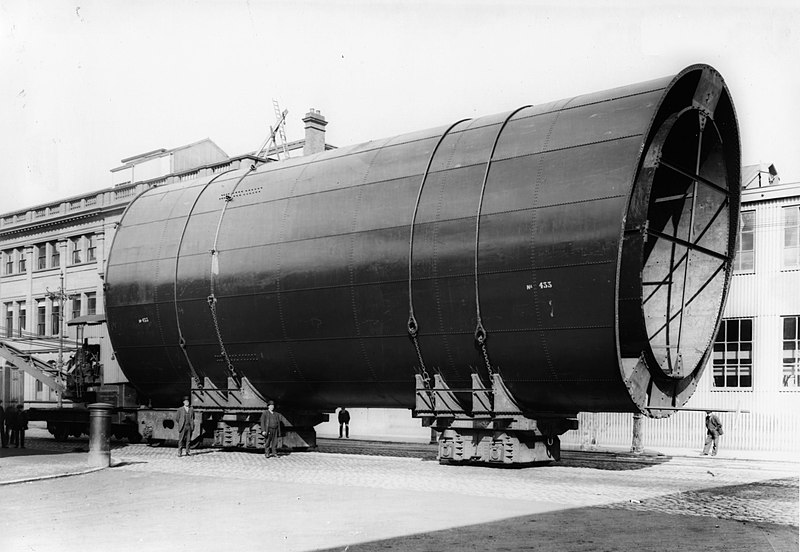

Back in 1907, Director General of the White Star Line J. Bruce Ismay planned a series of three sister ships, to compete with the Cunard lines’ Mauritania, and Lusitania. What these lacked in speed would be made up in size, and luxurious comfort. The three vessels were to be named Olympic, Titanic and Gigantic.

That last name was quietly changed following the Titanic disaster and, on December 12, 1915, the newly christened Britannic was ready for service.

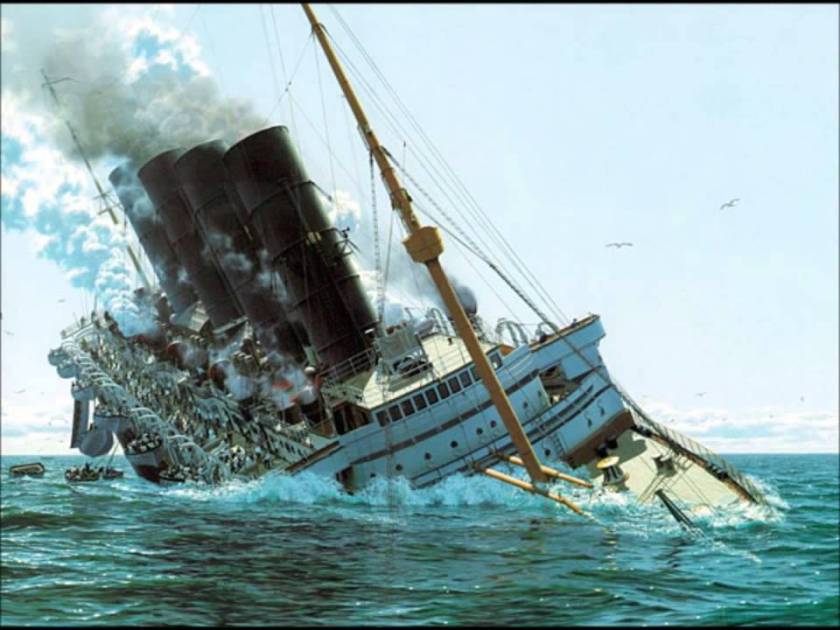

Four years later, the world was at war. Nurse Jessop was working aboard HMHS (His Majesty’s Hospital Ship) Britannic. On November 21, 1916, HMHS Britannic was on station near Kea in the Aegean Sea, when she was struck by a German mine, or torpedo. Violet Jessop calmly made her way to her cabin, She’d been here, before. There she collected a ring, a clock and a prayer book, and helped another nurse, collect her composure.

After the Carpathia rescue, Jessop complained to friends and family that she missed her toothbrush. Her brother Patrick had jokingly told her, next time you wreck, “look after your toothbrush”. This time, she didn’t forget it.

Britannic should have survived even with five watertight compartments filled, but nurses defied orders and opened the windows, to ventilate the wards. In fifty-five minutes, HMHS Britannic replaced her sister ship Titanic, as the largest vessel on the bottom of the sea.

Fortunately, daytime hours combined with warmer weather and more numerous lifeboats, to lessen the cost in lives. 1,035 were safely evacuated from the sinking vessel, keeping the death toll in the Britannic wreck, to thirty.

Violet Jessop survived three of the most famous shipwrecks of her age, and never tired of working at sea. She returned to work as stewardess aboard RMS Olympic after the war, before retiring to private life and passing away, in 1971.

John Maxtone-Graham, editor of “Titanic Survivor”, the story of her life, remembers one last story about “Miss Unsinkable”. Fifty-nine years after the wreck, the phone rang late one night, during a violent thunderstorm. A woman’s voice at the other end asked “Is this the Violet Jessop who was a stewardess on the Titanic and rescued a baby?” “Yes” came the reply, “who is this?” The woman laughed, and responded “I was that baby.”

If you enjoyed this “Today in History”, please feel free to re-blog, “like” & share on social media, so that others may find and enjoy it as well. Please click the “follow” button on the right, to receive email updates on new articles. Thank you for your interest, in the history we all share.

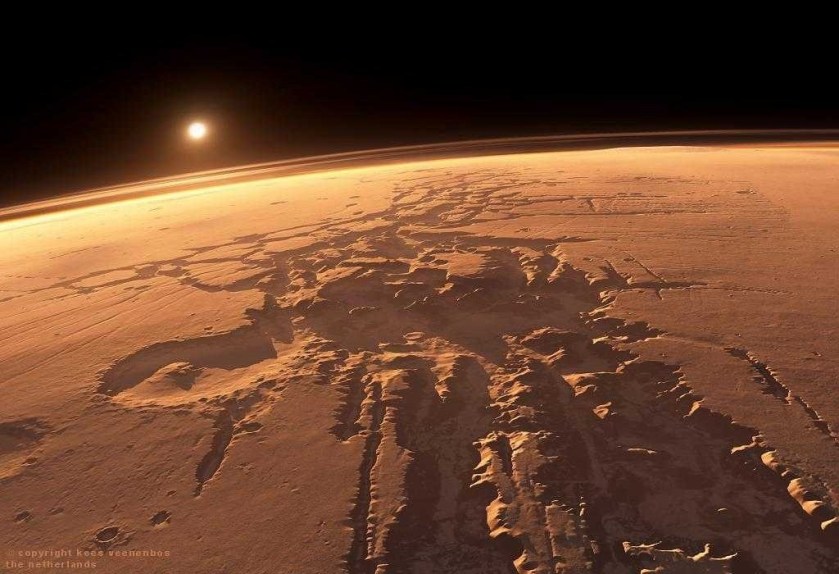

While much of “mainstream” science seems to steer clear of the subject, the University of California at Berkeley jumped in with both feet on this day in 1984, founding the SETI Institute for the “sharing [of] knowledge as scientific ambassadors to the public, the press, and the government”.

While much of “mainstream” science seems to steer clear of the subject, the University of California at Berkeley jumped in with both feet on this day in 1984, founding the SETI Institute for the “sharing [of] knowledge as scientific ambassadors to the public, the press, and the government”.

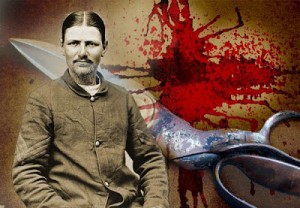

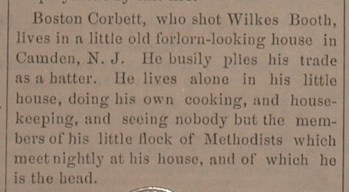

In the first months of the Civil War, Boston Corbett enlisted as a private in the 12th Regiment of the New York state militia. Eccentric behavior quickly got him into trouble. He would carry a bible with him at all times, reading passages aloud and holding unauthorized prayer meetings. He would argue with superior officers, once reprimanding Colonel Daniel Butterfield for using profane language and using the Lord’s name, in vain. That got him a stay in the guardhouse, where he continued to argue.

In the first months of the Civil War, Boston Corbett enlisted as a private in the 12th Regiment of the New York state militia. Eccentric behavior quickly got him into trouble. He would carry a bible with him at all times, reading passages aloud and holding unauthorized prayer meetings. He would argue with superior officers, once reprimanding Colonel Daniel Butterfield for using profane language and using the Lord’s name, in vain. That got him a stay in the guardhouse, where he continued to argue. On June 24, 1864, fifteen members of Corbett’s company were hemmed in and captured, by Confederate Colonel John Singleton Mosby’s men in Culpeper Virginia.

On June 24, 1864, fifteen members of Corbett’s company were hemmed in and captured, by Confederate Colonel John Singleton Mosby’s men in Culpeper Virginia.

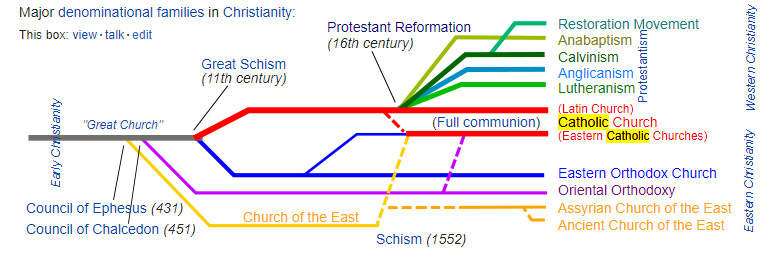

The prince-bishop’s forces fought their way through the streets of Münster for hours, killing some 600 Anabaptists before the city surrendered.

The prince-bishop’s forces fought their way through the streets of Münster for hours, killing some 600 Anabaptists before the city surrendered.

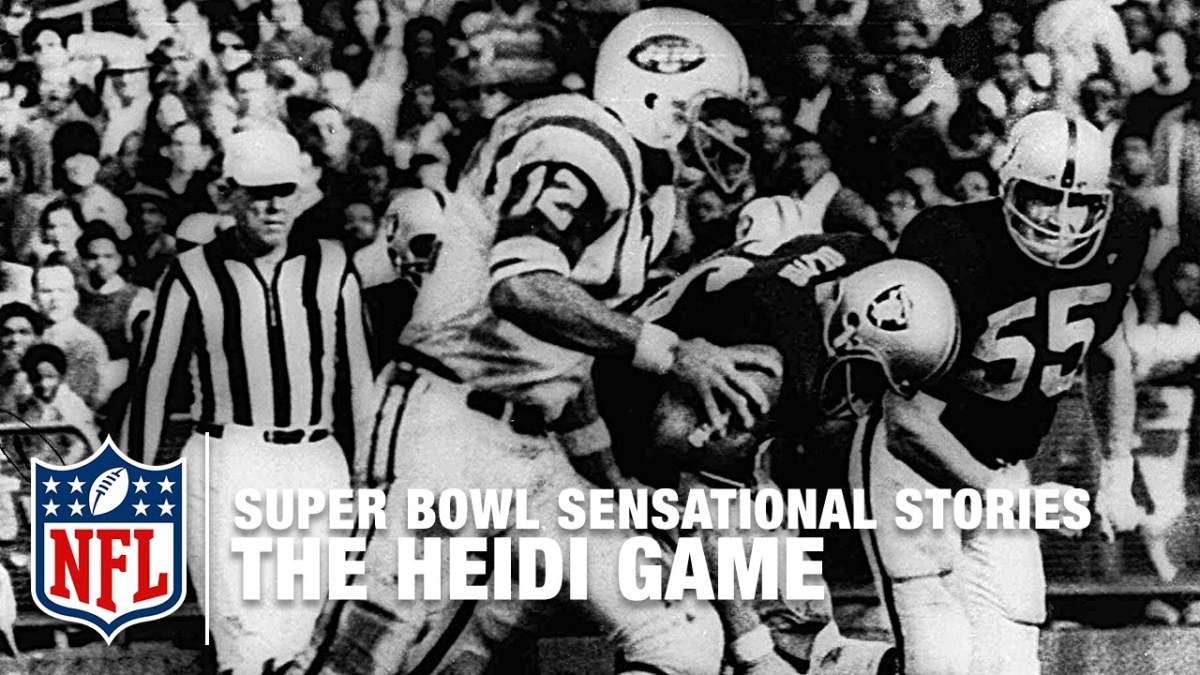

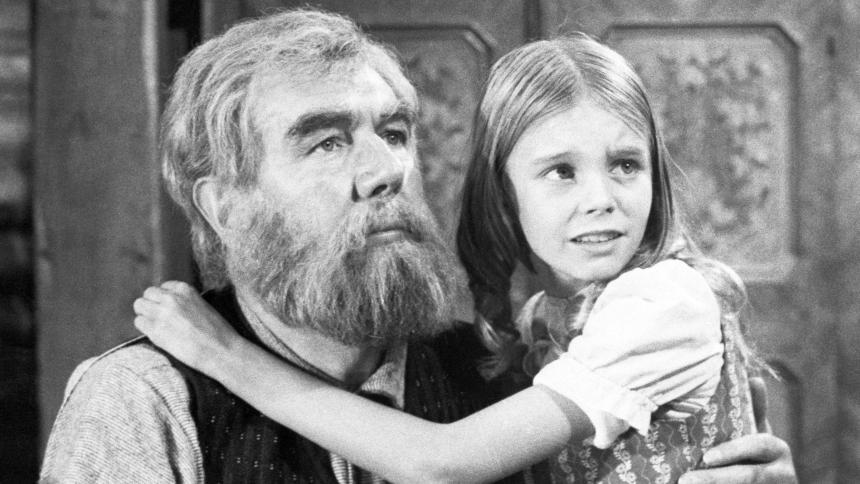

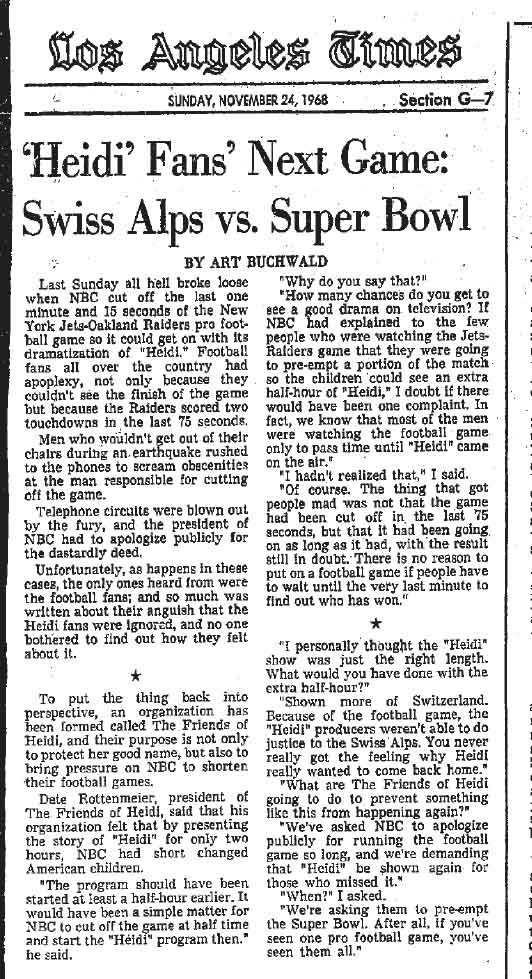

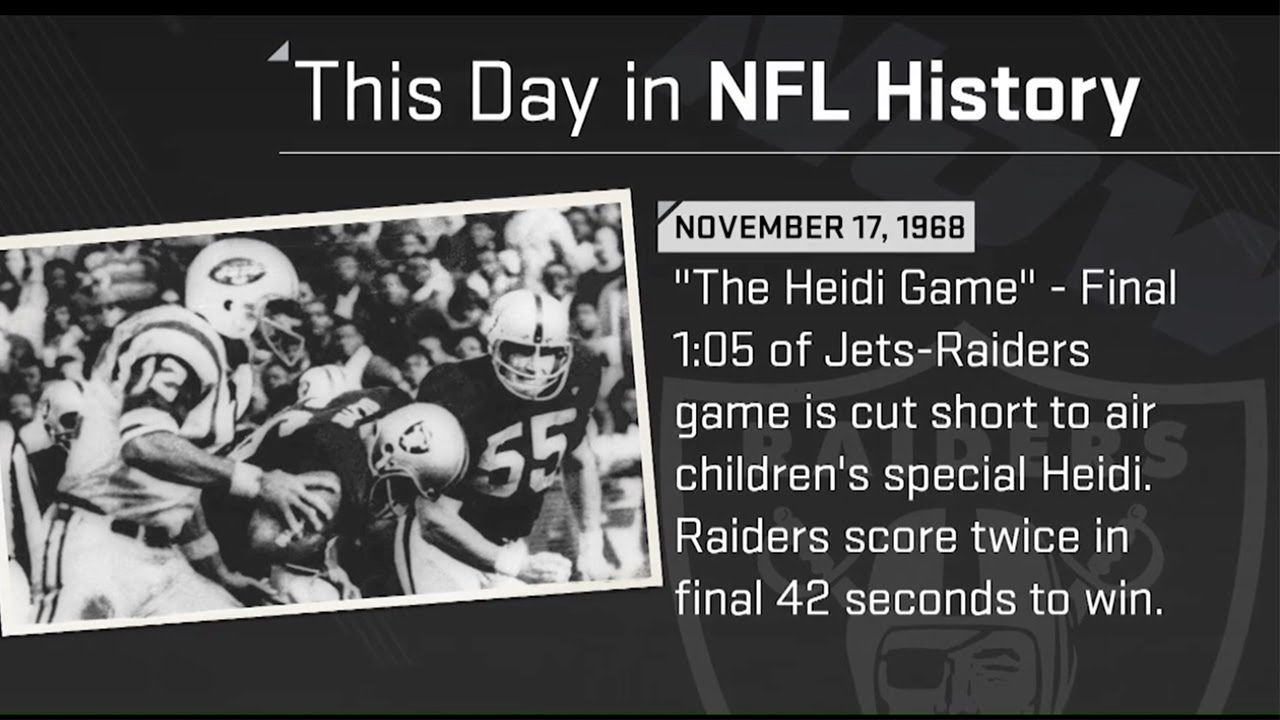

NBC executives, were thrilled. The AFL was only eight years old in 1968 and as yet unproven compared with the older league, the NFL/AFL merger still two years in the future.

NBC executives, were thrilled. The AFL was only eight years old in 1968 and as yet unproven compared with the older league, the NFL/AFL merger still two years in the future.

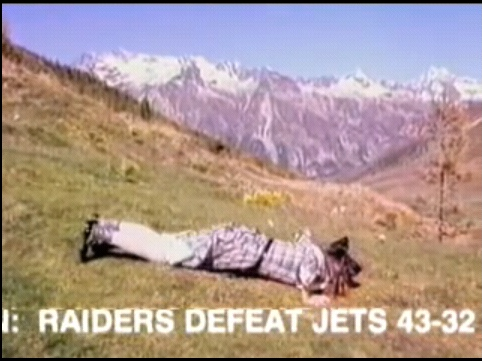

The “Heidi Bowl” was prime time news the following night, on all three networks. NBC’s Huntley-Brinkley Report aired the last sixty seconds while ABC Evening News anchor Frank Reynolds read excerpts from the movie, with clips of the Raiders’ two touchdowns cut in. CBS Evening News’ Harry Reasoner announced the “result” of the game: “Heidi married the goat-herder“.

The “Heidi Bowl” was prime time news the following night, on all three networks. NBC’s Huntley-Brinkley Report aired the last sixty seconds while ABC Evening News anchor Frank Reynolds read excerpts from the movie, with clips of the Raiders’ two touchdowns cut in. CBS Evening News’ Harry Reasoner announced the “result” of the game: “Heidi married the goat-herder“.

Admiral Rodney pretty much had his way. The census of 1790 shows 8,124 on the Dutch island nation. In 1950, the population stood at only 790. It would take 150 years from Rodney’s departure, before tourism even began to restore the economic well-being of the tiny island.

Admiral Rodney pretty much had his way. The census of 1790 shows 8,124 on the Dutch island nation. In 1950, the population stood at only 790. It would take 150 years from Rodney’s departure, before tourism even began to restore the economic well-being of the tiny island.

“Greyfriar’s Bobby” was a Skye Terrier in 19th-century Edinburgh, who waited 14 years by the grave of his owner, Police nightwatchman, John Gray. There he died in 1872 and was buried in the Greyfriars Kirkyard, not far from where his master lay.

“Greyfriar’s Bobby” was a Skye Terrier in 19th-century Edinburgh, who waited 14 years by the grave of his owner, Police nightwatchman, John Gray. There he died in 1872 and was buried in the Greyfriars Kirkyard, not far from where his master lay. Ruswarp was a fourteen-year old Border Collie who went hiking with Graham Nuttall on January 20, 1990 in the Welsh Mountains, near Llandrindod. On April 7, a hiker discovered Nuttall’s body near a mountain stream, where the dog had been standing guard for eleven weeks. Ruswarp was so weak he had to be carried off the mountain, and died shortly after. Today, there is a statue in his memory, on a platform near the Garsdale railway station.

Ruswarp was a fourteen-year old Border Collie who went hiking with Graham Nuttall on January 20, 1990 in the Welsh Mountains, near Llandrindod. On April 7, a hiker discovered Nuttall’s body near a mountain stream, where the dog had been standing guard for eleven weeks. Ruswarp was so weak he had to be carried off the mountain, and died shortly after. Today, there is a statue in his memory, on a platform near the Garsdale railway station.

“The Wall” was dedicated on this day, November 13, 1982. Thirty-one years later, we had come to pay a debt of honor to Uncle Gary’s shipmates, the 134 names inscribed on panel 24E, victims of the 1967 disaster aboard the Supercarrier, USS Forrestal.

“The Wall” was dedicated on this day, November 13, 1982. Thirty-one years later, we had come to pay a debt of honor to Uncle Gary’s shipmates, the 134 names inscribed on panel 24E, victims of the 1967 disaster aboard the Supercarrier, USS Forrestal.

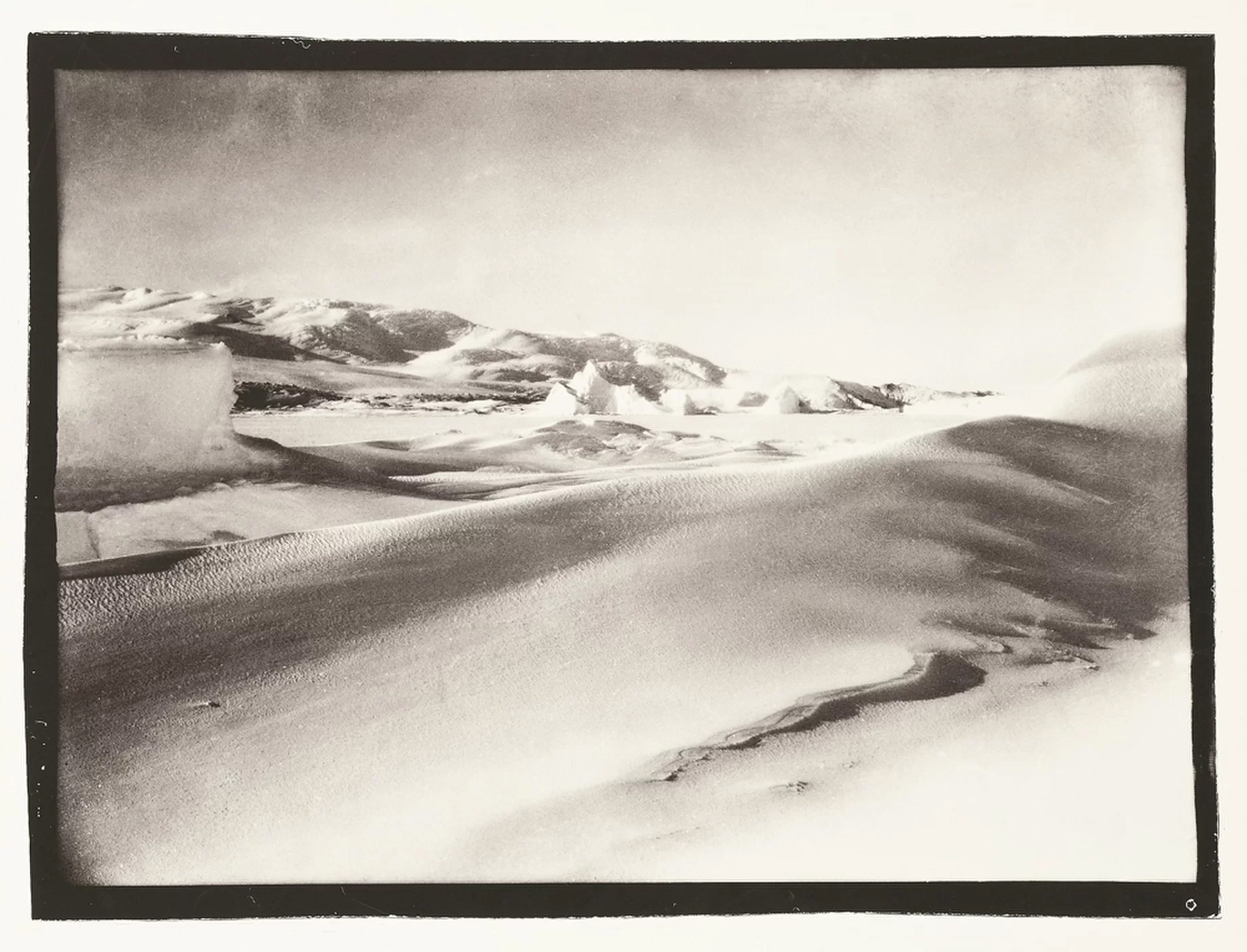

As long as he could remember, Roald Amundsen wanted to be an explorer. As a boy, he would read about the doomed Franklin Arctic Expedition, of 1848. A sixteen-year-old Amundsen took inspiration from Fridtjof Nansen’s epic crossing of Greenland, in 1888.

As long as he could remember, Roald Amundsen wanted to be an explorer. As a boy, he would read about the doomed Franklin Arctic Expedition, of 1848. A sixteen-year-old Amundsen took inspiration from Fridtjof Nansen’s epic crossing of Greenland, in 1888. In the Royal Navy, limited opportunities for career advancement were eagerly sought after, by any number of ambitious officers. Home on leave in 1899, Scott chanced once again to meet the now-knighted “Sir” Clements Markham, and learned of an impending RGS Antarctic expedition, aboard the barque-rigged auxiliary steamship, RRS Discovery. What passed between the two went unrecorded but, a few days later, Scott showed up at the Markham residence, and volunteered to lead the expedition.

In the Royal Navy, limited opportunities for career advancement were eagerly sought after, by any number of ambitious officers. Home on leave in 1899, Scott chanced once again to meet the now-knighted “Sir” Clements Markham, and learned of an impending RGS Antarctic expedition, aboard the barque-rigged auxiliary steamship, RRS Discovery. What passed between the two went unrecorded but, a few days later, Scott showed up at the Markham residence, and volunteered to lead the expedition.

You must be logged in to post a comment.