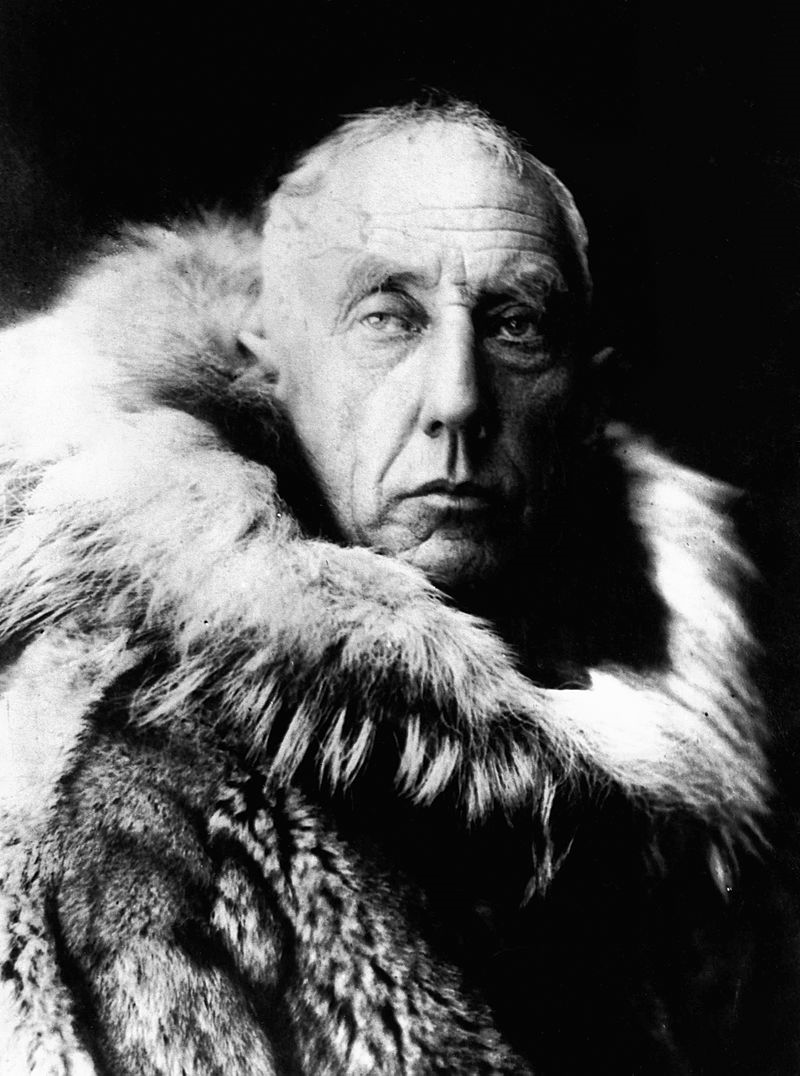

As long as he could remember, Roald Amundsen wanted to be an explorer. As a boy in Norway, he would read about the doomed Franklin Expedition to the Arctic, in 1848. As a sixteen-year-old, Amundsen was captivated by Fridtjof Nansen’s epic crossing of Greenland, in 1888.

The period would come to be known as the “Heroic Age” of polar exploration. Roald Amundsen was born to take part.

Not so, Robert Falcon Scott. A career officer with the British Royal Navy, Scott would take a different path to this story.

Clements Markham, President of the British Royal Geographical Society (RGS), was known to “collect” promising young naval officers with an eye toward future polar exploration. The two first met on March 1, 1887, when the eighteen-year old midshipman’s cutter won a sailing race, across St. Kitt’s Bay.

In 1894, Scott’s father John made a disastrous mistake, selling the family brewery and investing the proceeds, badly. The elder Scott’s death of heart disease three years later brought on fresh family crisis, leaving John’s widow Hannah and her two unmarried daughters, dependent on Robert and his younger brother, Archie.

Now more than ever, Scott was eager to distinguish himself with an eye toward promotion, and the increase in income to be expected, with it.

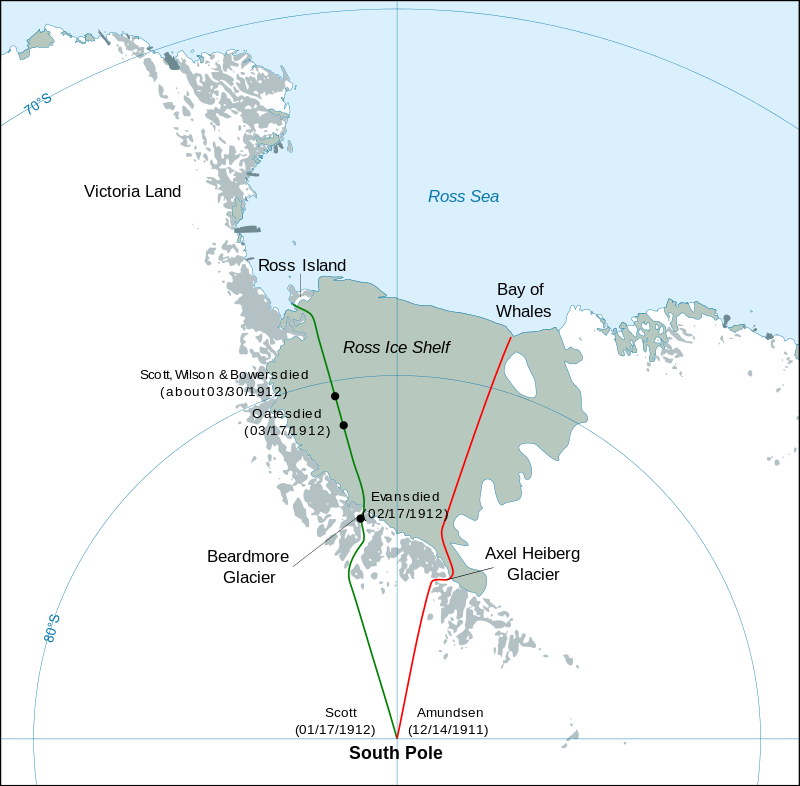

In the Royal Navy, limited opportunities for career advancement were aggressively sought after, by any number of ambitious officers. Home on leave in 1899, Scott chanced once again to meet the now-knighted “Sir” Clements Markham, and learned of an impending RGS expedition to the Antarctic, aboard the barque-rigged auxiliary steamship, RRS Discovery.

What passed between the two went unrecorded but, a few days later, Scott showed up at the Markham residence and volunteered to lead the expedition.

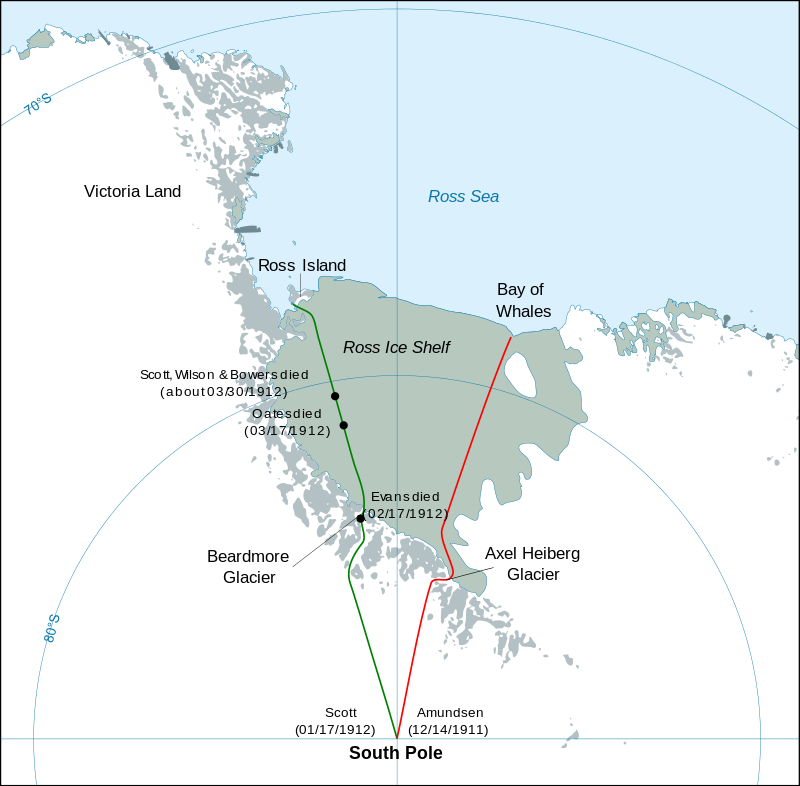

The Discovery expedition of 1901-’04 was one of science as well as exploration. Despite a combined polar experience of near-zero, the fifty officers and men under Robert Falcon Scott made a number of important biological, zoological and geological findings, proving the world’s southernmost continent was at one time, forested. Though later criticized as clumsy and amateurish, a journey south in the direction of the pole discovered the polar plateau, establishing the southernmost record for this time at 82° 17′ S. Only 530 miles short of the pole.

Discovery returned in September 1904, the expedition hailed by one writer as “one of the great polar journeys”, of its time. Once an obscure naval officer, Scott now entered Edwardian society, moving among the higher social and economic circles, of the day.

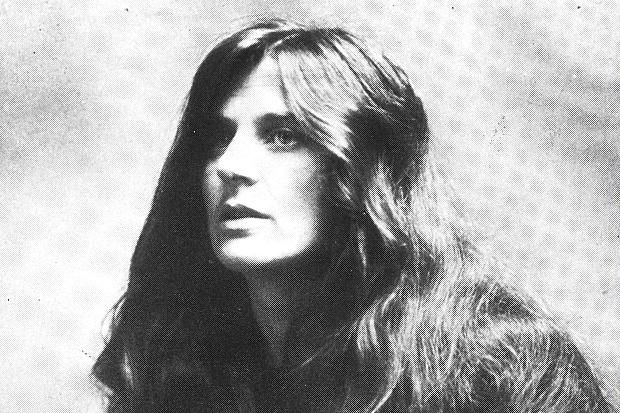

A brief but stormy relationship ensued with Kathleen Bruce, a sculptress who studied under Auguste Rodin and counted among her personal friends, the likes of Pablo Picasso, Aleister Crowley and Isadora Duncan. The couple was married on September 2, 1908 and the marriage produced one child. Peter Markham Scott would grow up to found the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

The elder Scott would never live to see it.

The “Great Southern Journey” of Scott’s Discovery officer Ernest Shackleton, arrived 112 miles short of the pole on January 9, 1909, providing Scott with the impetus for a second attempt, the following year. Scott was still fundraising for the expedition when the old converted whaler Terra Nova departed Cardiff, in South Wales. Scott joined the ship in South Africa and arrived in Melbourne Australia in October, 1910.

Meanwhile, and unbeknownst to Scott, Roald Amundsen was preparing for his own drive on the south pole, aboard the sailing vessel, “Fram” (Forward).

Scott was in Melbourne when he received the telegram: “Beg leave to inform you Fram proceeding Antarctic Amundsen“. Robert Falcon Scott now faced a race to the pole.

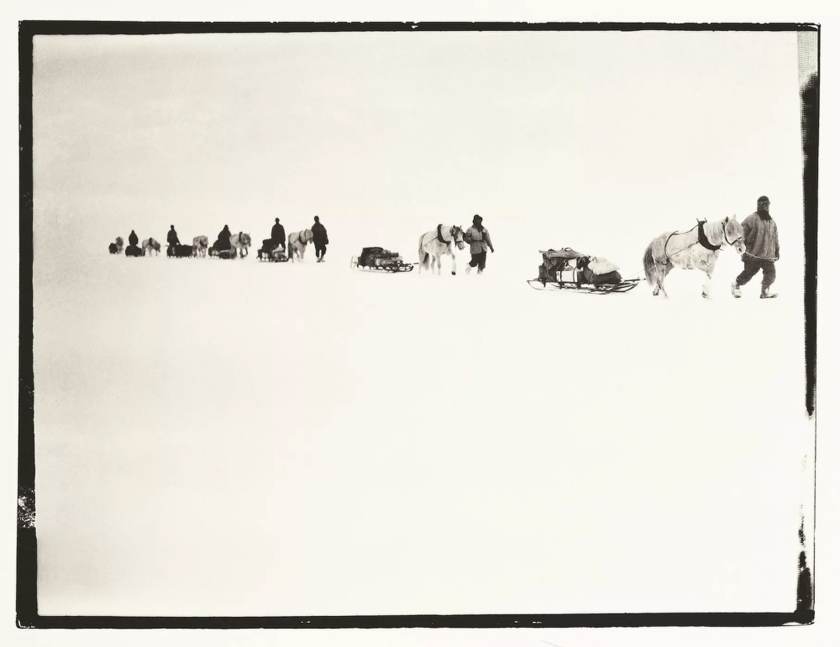

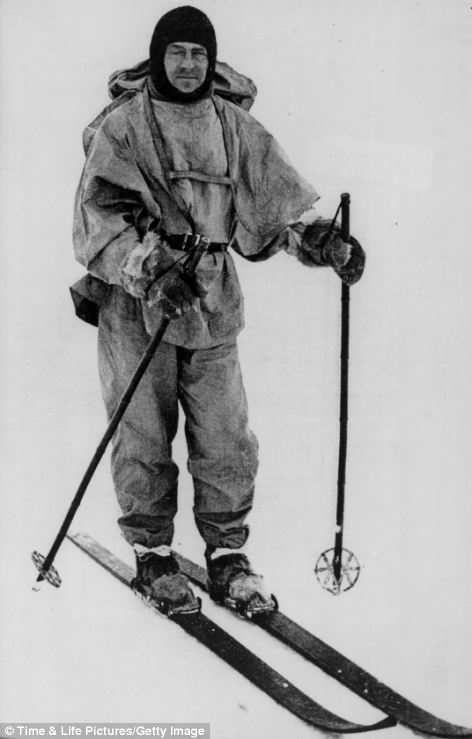

Unlike Amundsen who adopted the lighter fur-skins of the Inuit, the Scott expedition wore heavy wool clothing, depending on motorized and horse-drawn transport and man-hauling sledges for the final drive across the polar plateau. Dog teams were expected to meet them only on the way out, on March 1.

Ponies, poorly acclimatized and weakened by the wretched conditions of Antarctica, slowed the depot-laying part of the Scott expedition. Four horses died of cold or had to be shot, because they slowed the team.

Expedition member Lawrence “Titus” Oates warned Scott against the decision to locate “One-Ton Depot” at 80°, 35-miles short of the planned location. “Sir, I’m afraid you’ll come to regret not taking my advice.” Titus’ words would prove prophetic.

Unlike the earlier attempt, Robert Falcon Scott made it to the pole this time. Amundsen’s Norwegian team had beat him. By a mere five weeks. A century later you can still feel the man’s anguish, by the words in his diary: “The worst has happened…All the day dreams must go…Great God! This is an awful place”.

Utterly Defeated, the five-man Scott party turned to begin the 800-mile, frozen slog back from the Pole on January 19, 1912. By the 23rd, the condition of Petty Officer Edgar “Taff” Evans, began to deteriorate . On February 4, a bad fall on Beardmore Glacier left the man concussed, “dull and incapable”. A second fall two weeks later left the man dead at the foot of the glacier.

The appointed time came and went in early March and the dog teams, failed to materialize. Severely frostbitten, Lawrence Oates struggled on. Soldier, explorer, he was “No Surrender Oates”, a moniker earned years before when he refused to surrender before a superior force in the Boer Wars. In the end, it was impossible to go on.

Lawrence Oates knew he was holding up the team. There was but one option and leaving that tent, was a deliberate act. Final. Suicidal.

Scott’s diary tells us the story:

March 16, 1912 “He was a brave soul. This was the end. He slept through the night before last, hoping not to wake; but he woke in the morning – yesterday. It was blowing a blizzard. He said, ‘I am just going outside and may be some time.’ He went out into the blizzard and we have not seen him since.”

His body was never found.

The last three made final camp on March 19, with 11 miles to go before the next food and supply cache. A howling blizzard descended on the tents and lasted for days as Scott, Henry “Birdie” Bowers and Dr. Edward Wilson wrote good-bye letters to mothers, wives, and others.

March 22, 1912 “Blizzard bad as ever. Wilson and Bowers unable to start. Tomorrow last chance. No fuel and only one or two of food left — must be near the end. Have decided it shall be natural. We shall march for the depot with or without our effects and die in our tracks.”

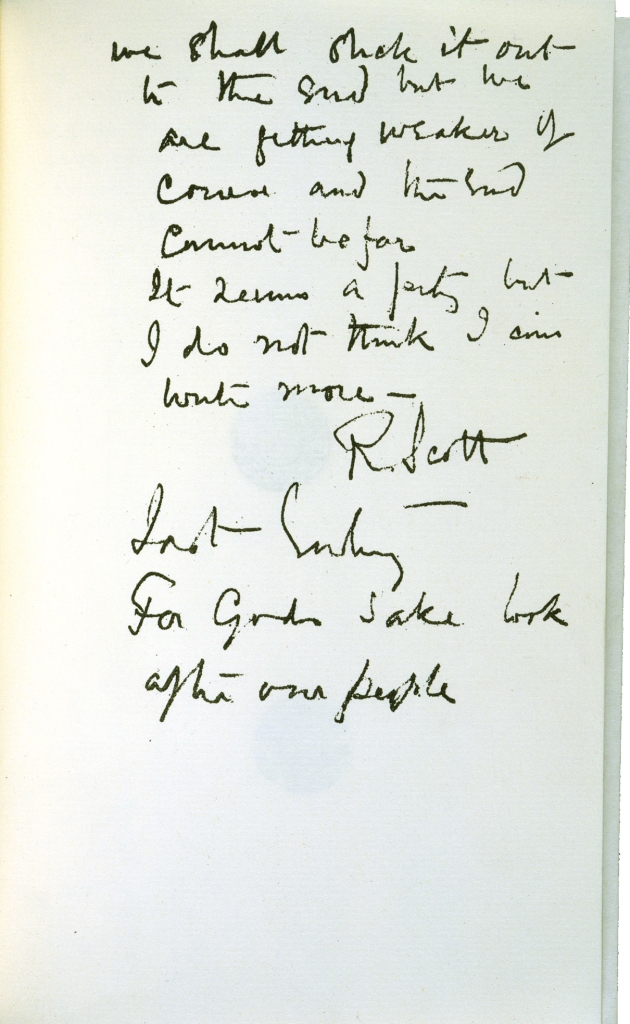

Starving, frostbitten, Robert Falcon Scott wrote to his diary during the final hours of his life.

March 29, 1912 “We had fuel to make two cups of tea apiece and bare food for two days on the 20th. Every day we have been ready to start for our depot 11 miles away, but outside the door of the tent it remains a scene of whirling drift. I do not think we can hope for any better things now. We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far.

It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more.

R. SCOTT.

The frozen corpses of Robert Falcon Scott and his comrades were found on November 12, 1912. You can almost feel his frozen, dying fingers in the words on that final page, written back on March 29:

“Last entry. For God’s sake look after our people”.

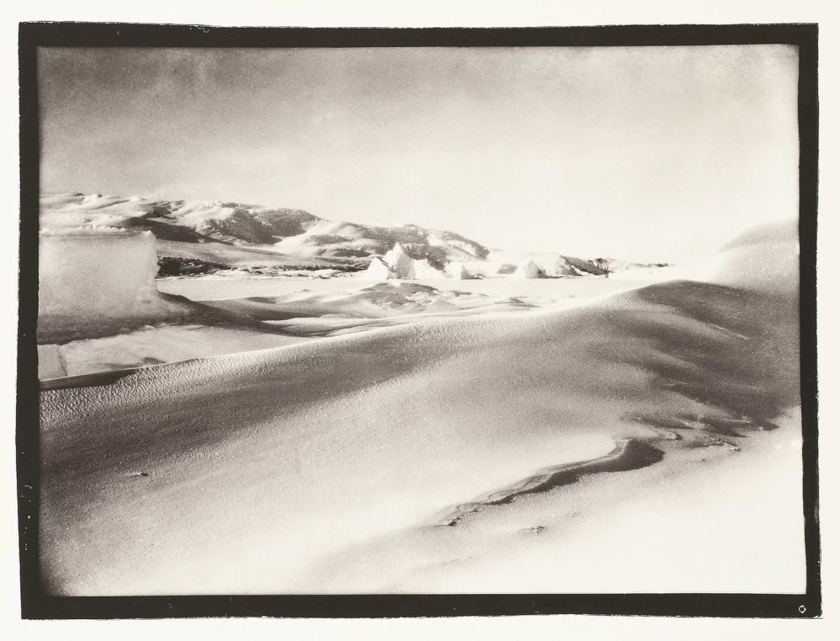

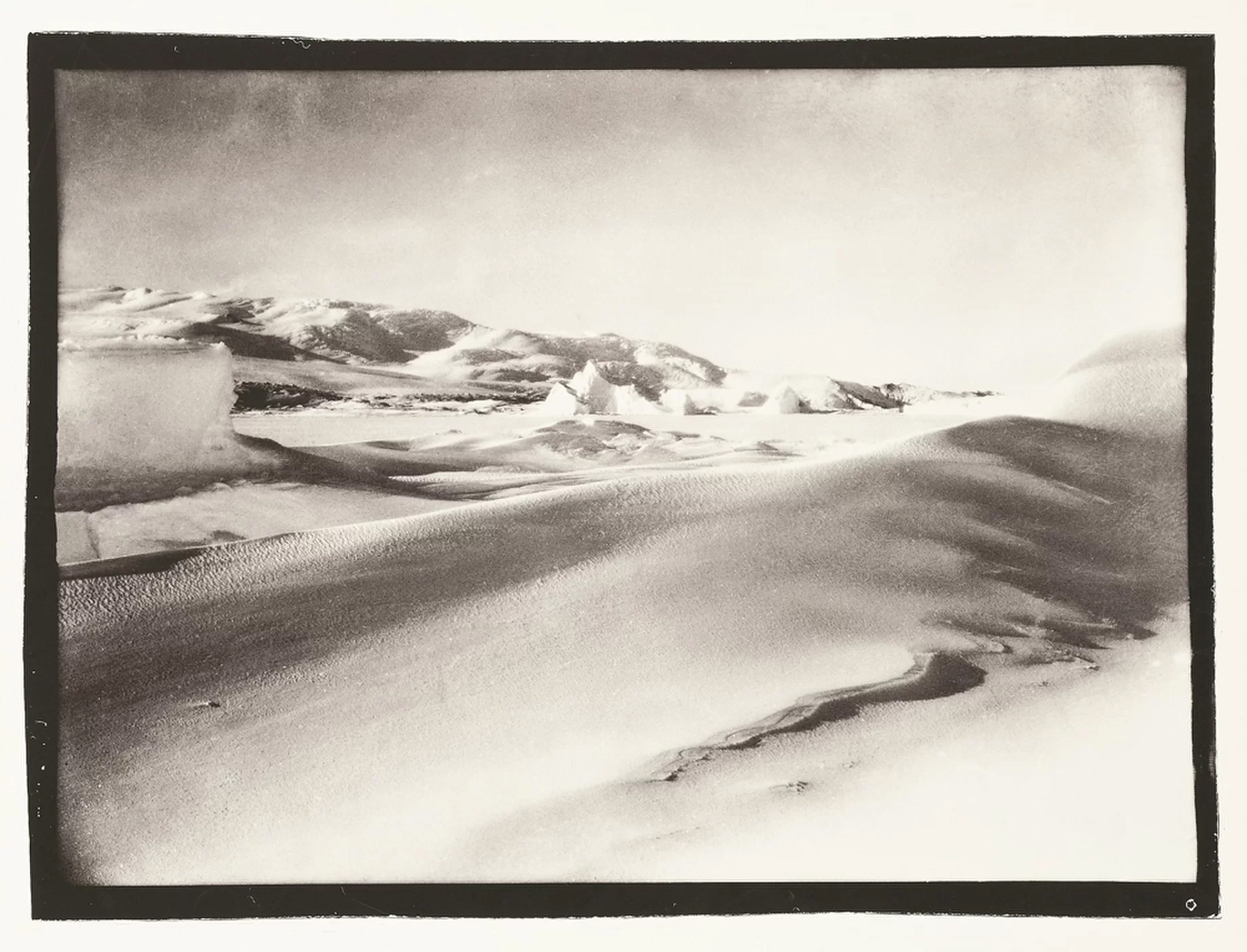

The lowest ground level temperature ever recorded was −128.6° Fahrenheit at the Soviet Vostok Antarctic Station, in 1983. Meteorological conditions for those last days in the Scott camp went unrecorded, and must only be imagined.

There are places in this world so inhospitable, the visitor is fortunate to get out alive. Where returning with the body of one not so lucky, is impossible. The frozen side of Everest is such a place where no fewer than 300 climbers have perished, in the last six decades. A third of them, will never come down.

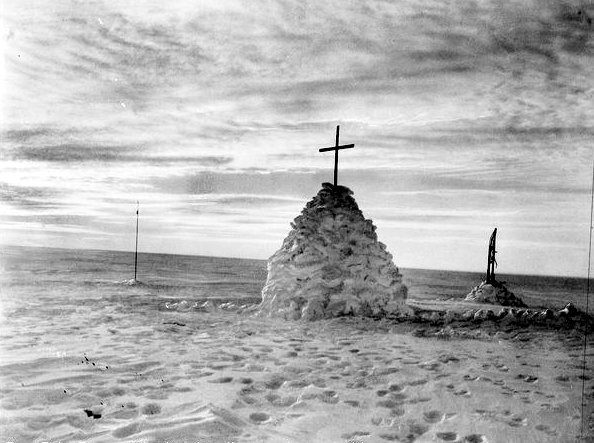

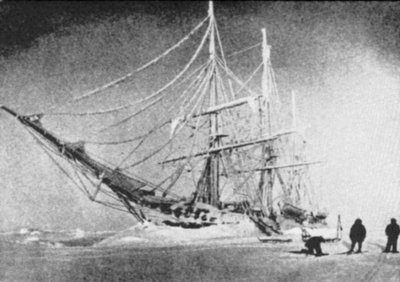

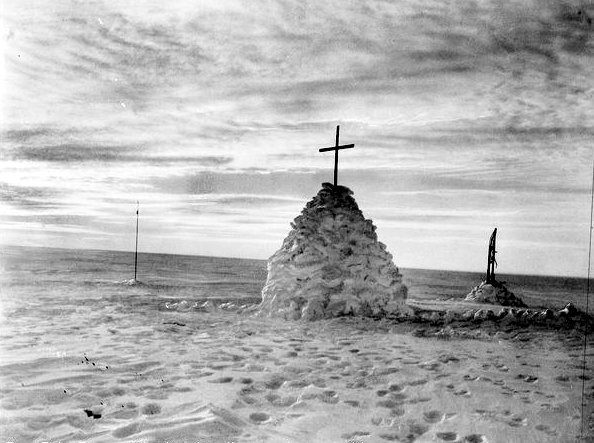

The final camp, is such a place. A high cairn of snow was erected over it all, that final camp becoming the three men’s tomb. Ship’s carpenters built a wooden cross, inscribing on it the names of those lost: Scott, Edward Wilson, Henry Bowers, Lawrence Oates and Edgar Evans. A line from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem, Ulysses, was carved into the cross:

“To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield”.

If only they’d been able to make it, that next eleven miles.

On hearing the fate of his rival, Amundsen said “I would gladly forgo any honor or money if thereby I could have saved Scott his terrible death”.

More than a century later, ice and snow have covered the last camp of the southern party. Pressed ever downward by the weight of snow and ice, their corpses are encased seventy-five-feet down now in the Ross Ice Shelf, inching their way outward and expected to reach the Ross Sea sometime around 2276.

One day in a distant future none alive today will ever see, they will break off and float away, at the heart of some nameless iceberg.

Satellites measured the coldest temperature in recorded history on August 10, 2010 at −93.2 °C (−135.8 °F), in East Antarctica. The Amundsen-Scott weather station at the South Pole reports the average daily temperature for March, at -50.3°C (-58.54°F).

Satellites measured the coldest temperature in recorded history on August 10, 2010 at −93.2 °C (−135.8 °F), in East Antarctica. The Amundsen-Scott weather station at the South Pole reports the average daily temperature for March, at -50.3°C (-58.54°F).

As long as he could remember, Roald Amundsen wanted to be an explorer. As a boy, he would read about the doomed Franklin Arctic Expedition, of 1848. A sixteen-year-old Amundsen took inspiration from Fridtjof Nansen’s epic crossing of Greenland, in 1888.

As long as he could remember, Roald Amundsen wanted to be an explorer. As a boy, he would read about the doomed Franklin Arctic Expedition, of 1848. A sixteen-year-old Amundsen took inspiration from Fridtjof Nansen’s epic crossing of Greenland, in 1888.

Noble though it was, Lawrence Oates’ suicide came to naught. The last three made their final camp on March 19, with 400 miles to go. A howling blizzard descended on the tents the following day and lasted for days, as Scott, Henry “Birdie” Bowers and Dr. Edward Wilson wrote good-bye letters to mothers, wives, and others. In his final starved, frostbitten hours, Robert Falcon Scott wrote to his diary “It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more.” In his final entry, Scott worried about the financial burden on his family, and those of the doomed expedition: “Last entry. For God’s sake look after our people”.

Noble though it was, Lawrence Oates’ suicide came to naught. The last three made their final camp on March 19, with 400 miles to go. A howling blizzard descended on the tents the following day and lasted for days, as Scott, Henry “Birdie” Bowers and Dr. Edward Wilson wrote good-bye letters to mothers, wives, and others. In his final starved, frostbitten hours, Robert Falcon Scott wrote to his diary “It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more.” In his final entry, Scott worried about the financial burden on his family, and those of the doomed expedition: “Last entry. For God’s sake look after our people”. The last three survivors died eleven miles from their next supply depot.

The last three survivors died eleven miles from their next supply depot.

You must be logged in to post a comment.