The Lane Tech High school baseball team was at home on June 26, 1920. 10,000 spectators assembled to watch the game at Cubs Park, now Wrigley Field. New York’s Commerce High was ahead 8–6 in the top of the 9th, when a left handed batter hit a grand slam out of the park. No 17-year-old had ever hit a baseball out of a major league park before, and I don’t believe it’s happened, since. It was the first time the country heard the name, Lou Gehrig.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters that day, to set a team record. The loss didn’t matter to Paul Krichell, the Yankee scout who had been following Gehrig. Krichell didn’t care about the arm either, as much as he did that powerful, left-handed bat. He had seen Gehrig hit some of the longest home runs ever seen on several Eastern campuses, including a 450′ home run at Columbia’s South Field that cleared the stands and landed at 116th Street and Broadway.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters that day, to set a team record. The loss didn’t matter to Paul Krichell, the Yankee scout who had been following Gehrig. Krichell didn’t care about the arm either, as much as he did that powerful, left-handed bat. He had seen Gehrig hit some of the longest home runs ever seen on several Eastern campuses, including a 450′ home run at Columbia’s South Field that cleared the stands and landed at 116th Street and Broadway.

New York Giants manager John McGraw persuaded a young Gehrig to play pro ball under a false name, Henry Lewis, despite the fact that it could jeopardize his collegiate sports eligibility. He played only a dozen games for the Hartford Senators before being found out, and suspended for a time from college ball. This period, and a couple of brief stints in the minor leagues in the ’23 and ’24 seasons, were the only times Gehrig didn’t play for a New York team.

Gehrig started as a pinch hitter with the New York Yankees on June 15, 1923. He came into his own in the ‘26 season, in 1927 he batted fourth on “Murderers’ Row”; the first six hitters in the Yankee’s batting order: Earle Combs, Mark Koenig, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Bob Meusel and Tony Lazzeri.

He had one of the greatest seasons of any batter in history that year, hitting .373, with 218 hits: 52 doubles, 18 triples, 47 home runs, a then-record 175 RBIs, with a .765 slugging percentage. Gehrig’s bat helped the 1927 Yankees to a 110–44 record, the American League pennant, and a four game World Series sweep of the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Gehrig was the “Iron Horse”, playing in more consecutive games than any player in history. It was an “unbreakable” record, standing for 56 years, until surpassed in 1995 by Cal Ripken, Jr.

Gehrig hit his 23rd and last major league grand slam on August 20 1938, a record which would stand until fellow “Bronx Bomber” Alex Rodriquez tied it, in 2012.

Lou Gehrig collapsed in 1939 spring training, and went into an abrupt decline early in the season. Sports reporter James Kahn wrote: “I think there is something wrong with him. Physically wrong, I mean. I don’t know what it is, but I am satisfied that it goes far beyond his ball-playing”.

The team was in Detroit on May 2 when he told manager Joe McCarthy “I’m benching myself, Joe”. It’s “for the good of the team”. McCarthy put Babe Dahlgren in at first and the Yankees won 22-2, but that was it. The Iron Horse’s streak of 2,130 consecutive games, had come to an end.

The team was in Detroit on May 2 when he told manager Joe McCarthy “I’m benching myself, Joe”. It’s “for the good of the team”. McCarthy put Babe Dahlgren in at first and the Yankees won 22-2, but that was it. The Iron Horse’s streak of 2,130 consecutive games, had come to an end.

Gehrig left the team in June, arriving at the Mayo Clinic on the 13th. The diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) was confirmed six days later, on June 19. It was his 36th birthday. It was a cruel prognosis: rapidly increasing paralysis, difficulty in swallowing and speaking, and a life expectancy of fewer than three years.

Gehrig left the team in June, arriving at the Mayo Clinic on the 13th. The diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) was confirmed six days later, on June 19. It was his 36th birthday. It was a cruel prognosis: rapidly increasing paralysis, difficulty in swallowing and speaking, and a life expectancy of fewer than three years.

Gehrig briefly rejoined the Yankees in Washington, D.C. He was greeted by a group of Boy Scouts at Union Station, happily waving and wishing him luck. Gehrig waved back, but leaned forward to a reporter. “They’re wishing me luck”, he said, “and I’m dying.”

Gehrig appeared at Yankee Stadium on “Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day”, July 4, 1939, his once mighty body now so weakened by the disease which would take his name, as to barely be able to stand. Only two months earlier, manager Joe McCarthy had asked Babe Dahlgren to take the Iron Horse’s position. Now he asked the 1st baseman, to look out for his dying teammate. “If Lou starts to fall, catch him.”

Gehrig was awarded a series of trophies and other tokens of affection by the New York sports media, fellow players and groundskeepers. He would place each one on the ground, already too weak to hold them.

As the ceremony drew to a close, Master of Ceremonies Sid Mercer asked for a few words. Overwhelmed and struggling for control, Gehrig waved him off. The New York Times later wrote, “He gulped and fought to keep back the tears as he kept his eyes fastened to the ground”. 62,000 fans would have none of it. The chant went up. “We want Lou!” We want Lou!”

Eleanor Gehrig, a “tower of strength” throughout her husband’s ordeal, watched from a box seat. New York Daily News reporter Rosaleen Doherty wrote that she did not cry, “although all around us, women and quite a few men, were openly sobbing.”

At last, Lou Gehrig shuffled to the microphone, and began to speak. “For the past two weeks, you’ve been reading about a bad break.” As if the neurodegenerative disease destroying his body, was merely a “bad break.” He looked down and paused, as if trying to remember what to say. And then he delivered the most memorable line, of his life.

“Today, I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth.”

Henry Louis Gehrig died on June 2, 1941. He was 37.

I drove by Yankee Stadium a while back, and I thought of Lou Gehrig. It was right after the Boston Marathon bombing, in 2013. The sign out front said “United we Stand”. With it was a giant Red Sox logo. That night, thousands of Yankees fans interrupted a game with the Arizona Diamondbacks, to belt out Neil Diamond’s “Sweet Caroline,” a staple of Red Sox home games, since 1997.

I’ve always been a Boston guy myself, I think I’m required by Massachusetts state law to hate the Yankees. But seriously. They’re a class act..

This was the world of bare knuckle boxing in the age of John L. Sullivan. He thrived in that world. The urban prize ring was his “temple of manhood”. He intended to be its Crown Prince.

This was the world of bare knuckle boxing in the age of John L. Sullivan. He thrived in that world. The urban prize ring was his “temple of manhood”. He intended to be its Crown Prince.

Sullivan’s unbeaten record over 44 professional fights came to an end on July 9, 1892, when “Gentleman Jim” Corbett unloaded a smashing left in the 21st round that put the champion down, for good. Sullivan would later say that his opponent only “gave the finishing touches to what whiskey had already done to me.”

Sullivan’s unbeaten record over 44 professional fights came to an end on July 9, 1892, when “Gentleman Jim” Corbett unloaded a smashing left in the 21st round that put the champion down, for good. Sullivan would later say that his opponent only “gave the finishing touches to what whiskey had already done to me.”

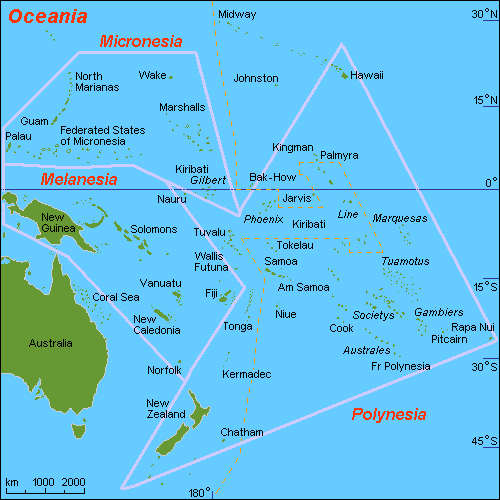

Raleigh believed that the Chesapeake afforded better opportunities for his new settlement, but Portuguese pilot Simon Fernandes, had other ideas. The caravan stopped at Roanoke Island in July, 1587, to check on the 15 men left behind a year earlier. Fernandes was a Privateer, impatient to resume his hunt for Spanish shipping. He ordered the colonists ashore on Roanoke Island.

Raleigh believed that the Chesapeake afforded better opportunities for his new settlement, but Portuguese pilot Simon Fernandes, had other ideas. The caravan stopped at Roanoke Island in July, 1587, to check on the 15 men left behind a year earlier. Fernandes was a Privateer, impatient to resume his hunt for Spanish shipping. He ordered the colonists ashore on Roanoke Island.

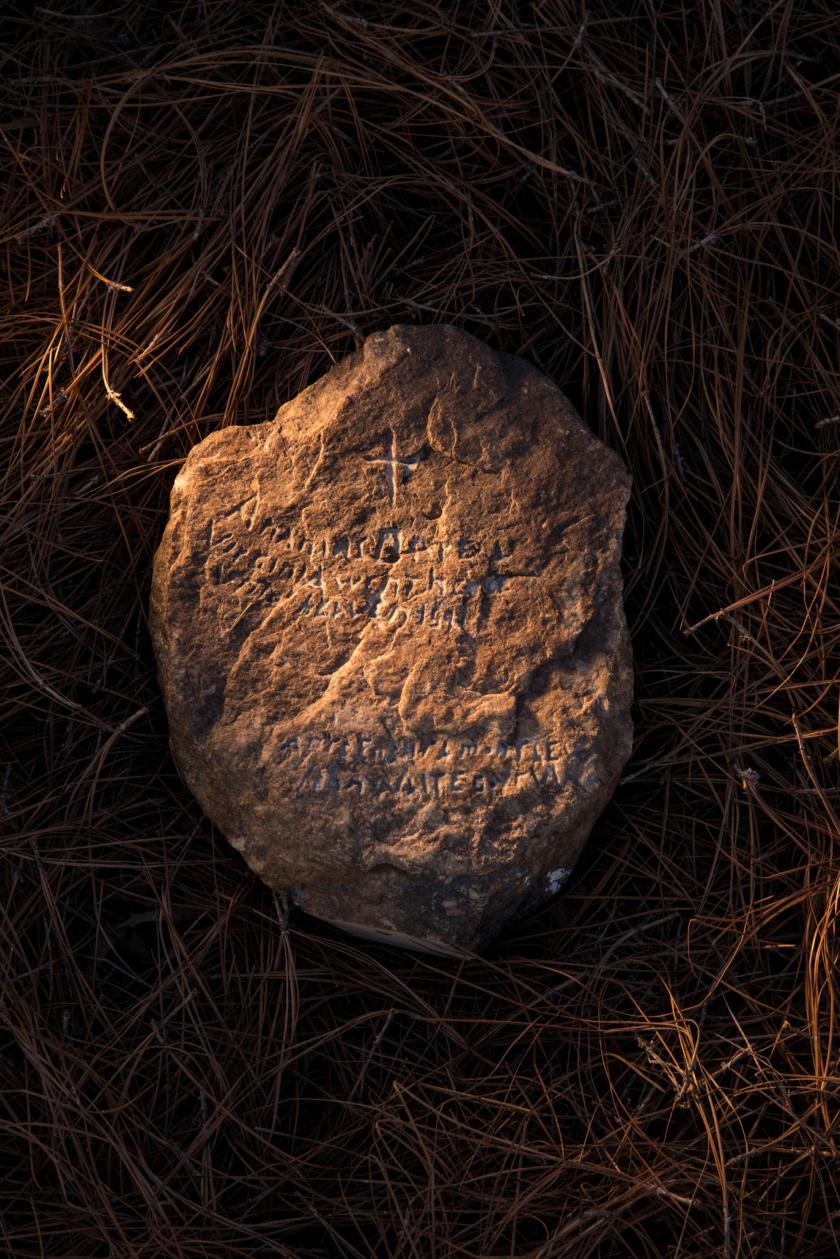

Research concluded at “Site X” in 2017, the cloak & dagger moniker given to deter thieves and looters. The mystery of the lost Colony of Roanoke, remains unsolved. “We don’t know exactly what we’ve got here,” admitted one archaeologist. “It remains a bit of an enigma.”

Research concluded at “Site X” in 2017, the cloak & dagger moniker given to deter thieves and looters. The mystery of the lost Colony of Roanoke, remains unsolved. “We don’t know exactly what we’ve got here,” admitted one archaeologist. “It remains a bit of an enigma.”

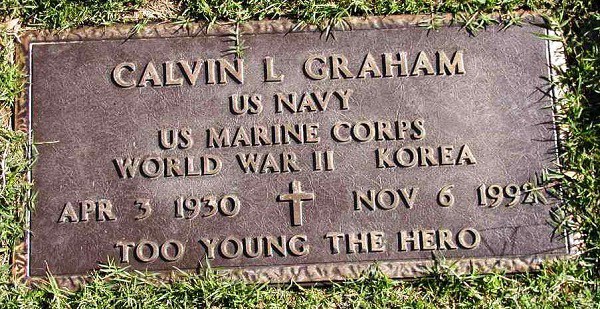

Being around newspapers allowed the boy to keep up on events overseas, “I didn’t like Hitler to start with“, he once told a reporter. By age eleven, some of Graham’s cousins had been killed in the war, and the boy wanted to fight.

Being around newspapers allowed the boy to keep up on events overseas, “I didn’t like Hitler to start with“, he once told a reporter. By age eleven, some of Graham’s cousins had been killed in the war, and the boy wanted to fight.

For the rest of his life, Calvin Graham fought for a clean service record, and for restoration of medical benefits. President Jimmy Carter personally approved an honorable discharge in 1978, and all Graham’s medals were reinstated, save for his Purple Heart. He was awarded $337 in back pay but denied medical benefits, save for the disability status conferred by the loss of one of his teeth, back in WW2.

For the rest of his life, Calvin Graham fought for a clean service record, and for restoration of medical benefits. President Jimmy Carter personally approved an honorable discharge in 1978, and all Graham’s medals were reinstated, save for his Purple Heart. He was awarded $337 in back pay but denied medical benefits, save for the disability status conferred by the loss of one of his teeth, back in WW2.

Born and raised in Austria, Greta Zimmer was 16 years old, in 1939. Fearful of the war bearing down on them, Greta’s parents sent her and her two sisters to America, not knowing if they’d ever see each other again.

Born and raised in Austria, Greta Zimmer was 16 years old, in 1939. Fearful of the war bearing down on them, Greta’s parents sent her and her two sisters to America, not knowing if they’d ever see each other again. The couple went to a movie at Radio City Music Hall, but the film was interrupted by a theater employee who turned on the lights, announcing that the war was over. Leaving the theater, the couple joined the tide of humanity moving toward Times Square.

The couple went to a movie at Radio City Music Hall, but the film was interrupted by a theater employee who turned on the lights, announcing that the war was over. Leaving the theater, the couple joined the tide of humanity moving toward Times Square.

Now Eisenstaedt and his Leica Illa rangefinder camera worked for Life Magazine, heading for Times Square in search of “The Picture™”.

Now Eisenstaedt and his Leica Illa rangefinder camera worked for Life Magazine, heading for Times Square in search of “The Picture™”.

Ford left the family farm outside of modern-day Detroit as a young man, never to return. His father William thought the boy would one day own the place but young Henry couldn’t stand farm work. He later wrote, “I never had any particular love for the farm—it was the mother on the farm I loved”.

Ford left the family farm outside of modern-day Detroit as a young man, never to return. His father William thought the boy would one day own the place but young Henry couldn’t stand farm work. He later wrote, “I never had any particular love for the farm—it was the mother on the farm I loved”.

Ford claimed he’d be able to “grow automobiles from the soil”, a hedge against the metal rationing of world War Two. He dedicated 120,000 acres of soybeans to experimentation, but to no end. The total acreage devoted to “fuel” production, is unrecorded.

Ford claimed he’d be able to “grow automobiles from the soil”, a hedge against the metal rationing of world War Two. He dedicated 120,000 acres of soybeans to experimentation, but to no end. The total acreage devoted to “fuel” production, is unrecorded. Henry Ford’s experiment in making cars from soybeans never got past that first prototype, and came to a halt during WW2. The project was never revived, though several states adopted license plates stamped out of soybeans, a solution farm animals found to be quite delicious.

Henry Ford’s experiment in making cars from soybeans never got past that first prototype, and came to a halt during WW2. The project was never revived, though several states adopted license plates stamped out of soybeans, a solution farm animals found to be quite delicious.

You must be logged in to post a comment.