The 16th century was drawing to a close when Queen Elizabeth set out to establish a permanent English settlement in the New World. The charter went to Walter Raleigh, who sent explorers Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe to scout out locations for a settlement.

The pair landed on Roanoke Island on July 4, 1584, establishing friendly relations with local natives, the Secotans and Croatans. They returned a year later with glowing reports of what is now the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Two Native Croatans, Manteo and Wanchese, accompanied the pair back to England. All of London was abuzz with the wonders of the New World.

Queen Elizabeth was so pleased that she knighted Raleigh. The new land was called “Virginia” in honor of the Virgin Queen.

Raleigh sent a party of 100 soldiers, miners and scientists to Roanoke Island, under the leadership of Captain Ralph Lane. The attempt was doomed from the start. They arrived too late in the season for planting, and Lane alienated a neighboring indigenous tribe when a misunderstanding led to the murder of Chief Wingina. That’ll do it.

By 1586 they had had enough, and left the island on a ship captained by Sir Francis Drake. Ironically, their supply ship arrived about a week later. Finding the island deserted, that ship left 15 men behind to “hold the fort” before they too, departed.

The now knighted “Sir” Walter Raleigh was not deterred. Raleigh recruited 90 men, 17 women and 9 children for a more permanent “Cittie of Raleigh”, appointing expedition artist John White, governor. Among this first colonial expedition were White’s pregnant daughter, Eleanor and her husband Ananias Dare, and the Croatans Wanchese and Manteo.

Raleigh believed that the Chesapeake afforded better opportunities for his new settlement, but Portuguese pilot Simon Fernandes, had other ideas. The caravan stopped at Roanoke Island in July, 1587, to check on the 15 men left behind a year earlier. Fernandes was a Privateer, impatient to resume his hunt for Spanish shipping. He ordered the colonists ashore on Roanoke Island.

Raleigh believed that the Chesapeake afforded better opportunities for his new settlement, but Portuguese pilot Simon Fernandes, had other ideas. The caravan stopped at Roanoke Island in July, 1587, to check on the 15 men left behind a year earlier. Fernandes was a Privateer, impatient to resume his hunt for Spanish shipping. He ordered the colonists ashore on Roanoke Island.

It could not have lifted the spirits of the small group to learn that the 15 left earlier, had disappeared.

Eleanor Dare gave birth to a daughter on August 18, 1587, and named her Virginia. Fernandez departed for England ten days later, taking along an anxious John White, who wanted to return to England for supplies. It was the last time that Governor White would see his family.

White found himself trapped in England by the invasion of the Spanish Armada, and the Anglo-Spanish war. Three years would come and go before White was able to return, and the Hopewell anchored off Roanoke. John White and a party of sailors waded ashore on August 18, 1590, three years to the day from the birth of his granddaughter, Virginia. There they found – nothing – save for footprints, and the letters “CRO”, carved into a nearby tree.

It was a prearranged signal. In case the colonists had to leave the island, they were to carve their destination into a tree or fence post. A cross would have been the sign that they left in an emergency, yet there was no cross.

Reaching the abandoned settlement, the party found the word CROATOAN, carved into a post. Again there was no cross, but the post was part of a defensive palisade, a defense against hostile attack which hadn’t been there when White left for England.

The word CROATOAN signified both the home of Chief Manteo’s people, the barrier island to the south, (modern-day Hatteras Island), and the indigenous people themselves.

White had hopes of finding his family but a hurricane came up, before he was able to explore much further. Ships and supplies were damaged requiring return to England. By this time, Raleigh was busy with a new venture in Ireland, and unwilling to support White’s return to the New World. Without deep pockets of his own, John White was never able to raise the resources to return.

Within the next twenty or so years, English colonists would put down roots in a place called Jamestown, and again in Plymouth. These roots would take hold and grow yet, what happened to that first such outpost, remains a mystery. Those 115 children, women and men, pioneers all, may have died of disease or starvation. They may have been killed by hostile natives. Perhaps they went to live with Chief Manteo’s people, after all.

One of the wilder legends has Virginia Dare, now a beautiful young maiden and example to European and Indian peoples alike, transformed into a snow white doe by a spurned and would-be suitor, the evil medicine man Chico.

The fate of the first English child born on American soil may never be known.

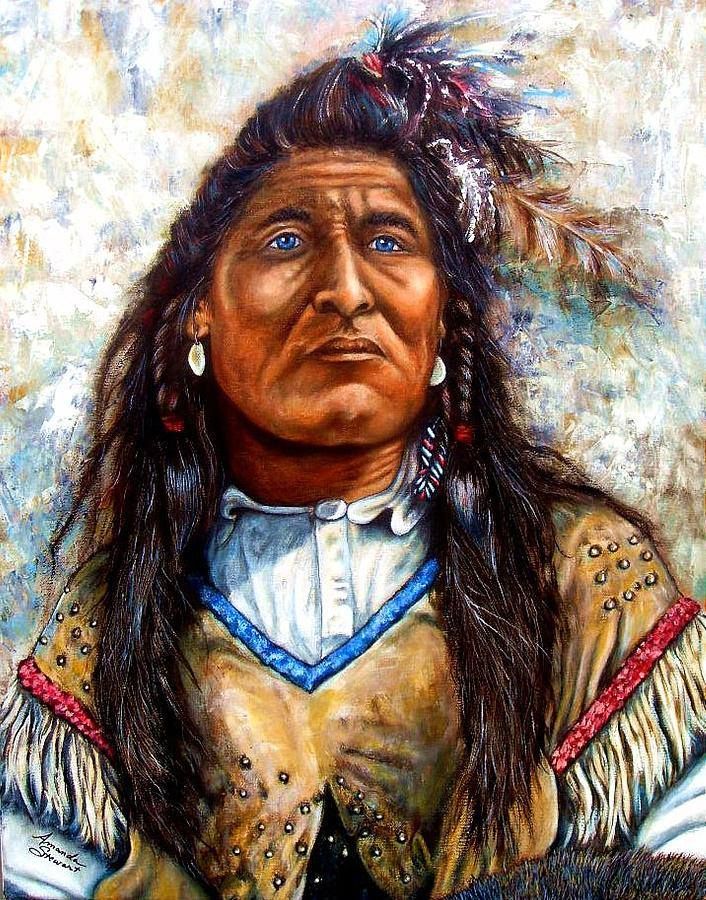

“An Indian girl shows off an English doll in one of many scenes painted by John White, the Lost Colony’s artist governor. White’s realistic portraits of Native American life—including ritual dances (shown here)—became one of the earliest lenses through which Europeans saw the New World”. H/T National Geographic

A personal anecdote involves a conversation I had with a woman in High Point, NC, a few years back. She described herself as having Croatoan ancestry, her family going back many generations on the outer banks of North Carolina. She described her Great Grandmother, a full blooded Croatoan. The woman looked like it, too, except for her crystal blue eyes. She used to smile at the idea of the lost colony of Roanoke. “They’re not lost“, she would say. “They are us“.

Afterward

Four hundred and twenty-eight years ago, the English colony at Roanoke Island vanished, along with the 115 men, women and children who lived there. Since that time, efforts to solve the mystery have concentrated on the island itself, with precious little to show for it.

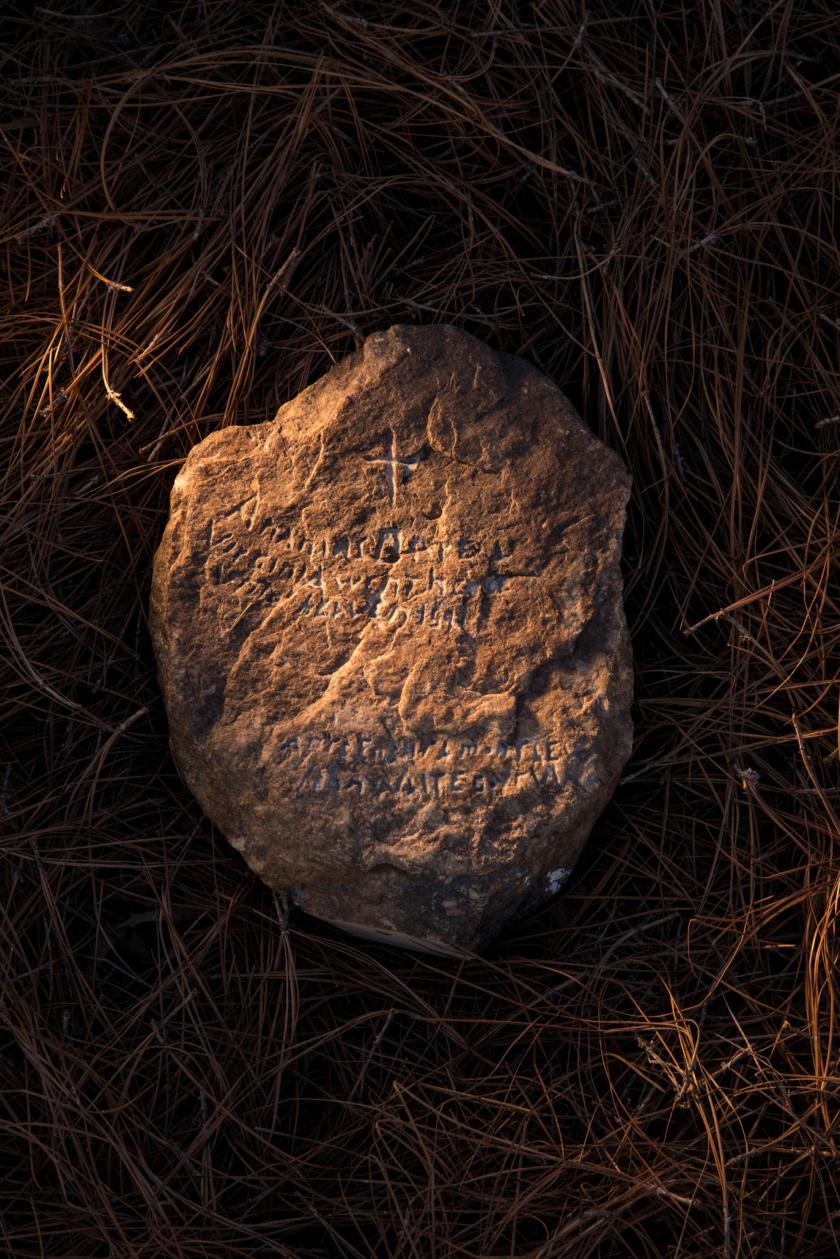

Approximately fifty “Dare Stones” have been discovered containing carved inscriptions, purporting to describe what happened to the lost colonists. Almost all have been debunked as hoaxes, yet research continues on at least one.

In 1993, a hurricane exposed large quantities of pottery and other remnants of a native American village, mixed with seemingly European artifacts. In the 1580s, Hatteras Island would have been an ideal spot, blessed with fertile soil for growing corn, beans and squash, and a bountiful coastline filled with scallops, oysters and fish.

Since then, two independent teams have found archaeological evidence, suggesting that the lost colonists may have split up and made their homes with native Americans. There are a number of European artifacts unlikely to be objects of trade, including a sword hilt, broken English bowls and the fragment of a writing slate, with one letter still visible. In 1998, Archaeologists discovered a 10-carat gold signet ring, a well worn Elizabethan-era object, almost certainly owned by an English nobleman.

Fifty miles to the northwest, the second team believes that they have unearthed pottery used by the lost colonists on the Albemarle Sound, near Edenton, North Carolina.

Research concluded at “Site X” in 2017, the cloak & dagger moniker given to deter thieves and looters. The mystery of the lost Colony of Roanoke, remains unsolved. “We don’t know exactly what we’ve got here,” admitted one archaeologist. “It remains a bit of an enigma.”

Research concluded at “Site X” in 2017, the cloak & dagger moniker given to deter thieves and looters. The mystery of the lost Colony of Roanoke, remains unsolved. “We don’t know exactly what we’ve got here,” admitted one archaeologist. “It remains a bit of an enigma.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.