In the late 1860s, French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi conceived a great work of neoclassical sculpture. An enormous statue depicting a female figure in robes, this latter-day colossus holding high her Torch of Progress and standing by the water’s edge to greet the weary traveler – to Egypt.

Today, the 120-mile Suez canal connecting the Mediterranean with the Red Sea handles nearly fifty ships per day. Around Bartholdi’s time, Ottoman authorities were just getting around to digging the thing. Bartholdi had visited Egypt as a young man, and came away captivated by the Sphinxes, the Great Pyramids, and now this.

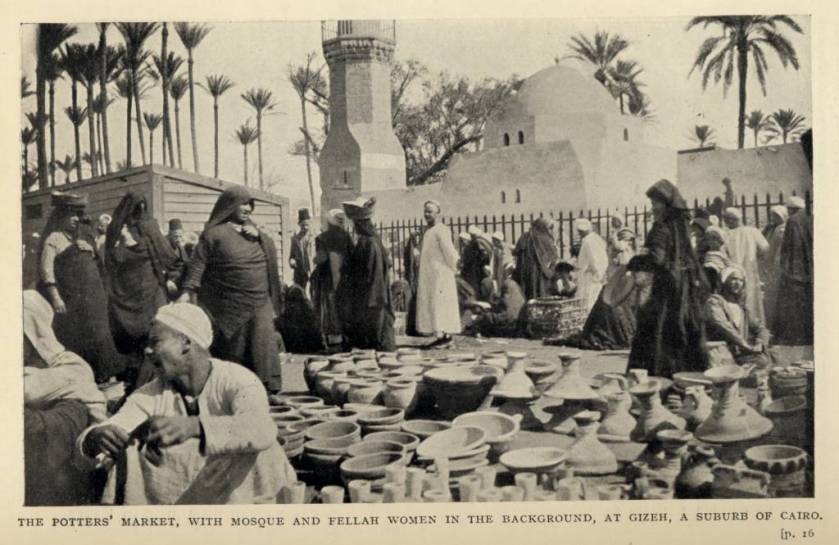

Bartholdi pitched his idea to the Khedive of Egypt in 1867, while attending the World’s Fair, in Paris. An enormous lighthouse in the form of a woman, holding high the lamp of welcome and dressed in the flowing cotton robe of the fellah, the “True Egyptian”, the peasant farmer and agricultural laborer of Egypt and North Africa.

The Egypt deal fell through, when Bartholdi came to a land where he’d never been before, to sell his colossus.

The idea was originally that of French attorney Édouard René de Laboulaye. An observer of American civic culture and passionate supporter for the Union side of the Civil War, Laboulaye wrote a three-volume work on the political history of the United States and considered the gift of “Liberty Enlightening the World” to be symbolic of values repressed at that time, by the 2nd Republique of Napoleon III.

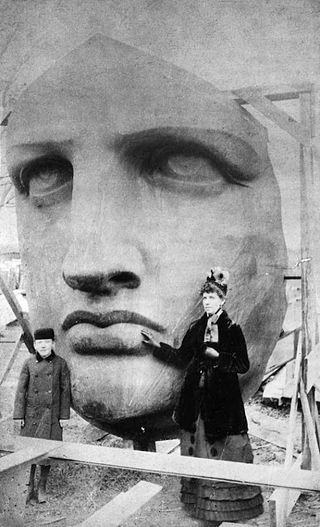

Bartholdi pitched the idea from Niagara Falls to Washington, D.C., from Chicago to Los Angeles, but Americans were slow to appreciate the idea of a lighthouse, in the shape of a woman. Back in Paris, the sculptor put on spectacles of every kind to raise money, charging visitors admission to the dusty workshop to watch the torch’s construction, and selling souvenirs. At one point, Bartholdi even petitioned the French government, to let him hold a national lottery.

The torch arrived late for the centennial festivities of 1876, celebrating the 100th birthday of the young nation. Nevertheless, the “colossal arm” proved popular with Philadelphia fairgoers, where visitors paid admission to climb up into the arm and take in the view from the balcony. The sculptor was so pleased that, for a time, he considered installing the finished statue in Philadelphia.

Fundraising committees were formed in New York, Philadelphia and Boston, to raise money for the foundation and pedestal. On his last full day in office, March 3, 1877, President Ulysses S Grant signed a joint resolution authorizing the President to accept the statue when presented by France, and to select a site for it. President Rutherford B. Hayes accepted Bartholdi’s suggestion and selected Bedloe’s Island, in New York Harbor.

Even then, fundraising went slowly for the New York committee.

With the full statue under construction in Paris, Boston made a play for the statue in 1882, offering to pay the full cost of installation provided that the statue was installed in Boston Harbor. The New York Times was miffed as only the “Newspaper of Record” can be. One editorial sniffed:

“[Boston] proposes to take our neglected statue of Liberty and warm it over for her own use and glory. Boston has probably again overestimated her powers. This statue is dear to us, though we have never looked upon it, and no third rate town is going to step in and take it from us. Philadelphia tried to do that in 1876, and failed. Let Boston be warned . . . that she can’t have our Liberty … that great light-house statue will be smashed into … fragments before it shall be stuck up in Boston Harbor”.

And here I thought that New York/Boston thing started with the Red Sox and the Yankees.

Fundraising toward the $100,000 required to complete the project was a constant and seemingly insurmountable challenge. New York Governor Grover Cleveland vetoed a bill in 1884, providing $50,000 for the effort. A bill to have the United States Congress pick the full tab the following year, was likewise defeated.

With only $3,000 in the bank, the American committee organized a number of fund drives. Poet Emma Lazarus was asked to donate an original work for auction, but declined the request. At the time, Lazarus was involved in aiding Jewish refugees from the anti-Semitic pogroms of Eastern Europe. In time, Lazarus came to see the request as a way to help the cause. The resulting sonnet, The New Colossus, included the iconic lines “Give me your tired, your poor/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

New York World publisher Joseph Pulitzer pushed the project over the top, offering to print names and brief notes from contributors of every size down to a single penny. It was a brilliant marketing scheme. Newspaper circulation went through the ceiling, as readers scooped up papers to see their names in print.

One kindergarten class in Davenport, Iowa raised $1.35. A group of children sent a dollar as “the money we saved to go to the circus with.” Another dollar was sent by a “lonely and very aged woman.” Even the Big Apple’s inebriates stepped up, when a Brooklyn home for alcoholics donated fifteen dollars. Not to be outdone, collection boxes were put out in bars and saloons all over New York City. (The two cities wouldn’t be merged until 1898).

Hundreds of crates containing the disassembled Liberty Enlightening the World arrived in New York on June 17, 1885, aboard the French steamer Isère. Two months later, the final piece fell into place. On August 11, the World announced that $102,000 had been raised from 120,000 donors. 80% of the total arrived in sums of a dollar or less.

Despite the fundraising success, the pedestal wasn’t complete until April of the following year. With no room to erect scaffolding, workers descended down ropes to install skin sections to an iron armature designed by none other than Gustave Eiffel.

The formal dedication was held on the afternoon of October 28, 1886, with former New York Governor and now-President of the United States Grover Cleveland, presiding. As many as a million turned out for the parade held that morning through the streets of the city. At the New York Stock Exchange, traders showered marchers with paper strips containing stock quotes, beginning an American tradition called the ticker-tape parade.

Festivities on the future Liberty Island were for dignitaries only that day, no member of the public was allowed. Ironically, no women were permitted at all for the dedication of the world’s tallest female, save for the Sculptor’s wife, and the granddaughter of French diplomat, Ferdinand de Lesseps. It was believed that women might be injured, in all that crush of humanity.

That didn’t keep a group of offended suffragists from chartering a boat, and getting as close to the island as possible. I wonder what that sounded like.

Liberty Enlightening the World has opened and closed to the public, since that time. She has turned from a dull copper red to the rich green patina you see today. She was injured in a World War, in the Black Tom explosion of 1916. She was there to witness Annie Moore’s arrival at Ellis Island, that 15-year-old “rosy-cheeked Irish girl” from County Cork, the first of some twenty-five million immigrants who arrived at that place legally between 1892 and 1924, helping to transform this nation into the international all-star team, of the world. She witnessed that Kiss on Times Square, ending another World War in Europe. Built in the wake of the Civil War, she has watched over a nation sometimes torn along lines of race and color, as her people learned to get along with others, unlike themselves.

She has witnessed the worst terror attack of modern history and that brief, shining moment where we all seemed to be “One Nation, Under God”. Throughout it all she has remained iconic. Torch held high, the chain at her feet lying broken as she walks forward. The stone tablet in her hand is inscribed “JULY IV MDCCLXXVI”. July 4, 1776.

I hate that statue. Liberty in the usa died in 1860 and really it’s become nothing but a symbol of immigration replacing decdants of founding stock and changing our culture and political system for the not better

LikeLike

I’m sorry you feel that way.

LikeLike

LOL ain’t your fault

LikeLike