On November 9, 2013, there occurred a gathering of four. A tribute to fallen heroes. These four were themselves heroes, and worthy of tribute. This was to be their last such gathering.

This story begins on April 18, 1942, when a flight of sixteen Mitchell B25 medium bombers took off from the deck of the carrier, USS Hornet. It was a retaliatory raid on Imperial Japan, planned and led by Lieutenant Colonel James “Jimmy” Doolittle of the United States Army Air Forces. It was payback for the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, seven months earlier. A demonstration that the Japanese home islands, were not immune from destruction.

Launching such massive aircraft from the decks of a carrier had never been attempted, and there were no means of bringing them back. With extra gas tanks installed and machine guns removed to save the weight, this was to be a one-way mission, into territory occupied by a savage adversary.

Fearing that mission security had been breached, the bomb run was forced to launch 200 miles before the intended departure spot. The range made fighter escort impossible, and left the bombers themselves with only the slimmest margin of error.

Japanese Premier Hideki Tojo was inspecting military bases, at the time of the raid. One B-25 came so close he could see the pilot, though the American bomber never fired a shot.

After dropping their bombs, fifteen continued west, toward Japanese occupied China. Unbeknownst at the time, carburetors bench-marked and calibrated for low level flight had been replaced in flight #8, which now had no chance of making it to the mainland. Twelve crash landed in the coastal provinces. Three more, ditched at sea. Pilot Captain Edward York pointed flight 8 toward Vladivostok, where he hoped to refuel. The pilot and crew were instead taken into captivity, and held for thirteen months.

Crew 3 Engineer-Gunner Corporal Leland Dale Faktor died in the fall after bailing out and Staff Sergeant Bombardier William Dieter and Sergeant Engineer-Gunner Donald Fitzmaurice bailed out of aircraft # 6 off the China coast, and drowned.

The heroism of the indigenous people at this point, is a little-known part of this story. The massive sweep across the eastern coastal provinces, the Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign, cost the lives of 250,000 Chinese. A quarter-million murdered by Japanese soldiers, in the hunt for Doolittle’s raiders. How many could have betrayed the Americans and refused, will never be known.

Amazingly, only eight were captured, among the seventy-seven survivors.

First Lieutenant Pilot “Bill” Farrow and Sergeant Engineer-Gunner Harold Spatz, both of Crew 16, and First Lieutenant Pilot Dean Edward Hallmark of Crew 6 were caught by the Japanese and executed by firing squad on October 15, 1942. Crew 6 Co-Pilot First Lieutenant Robert John Meder died in a Japanese prison camp, on December 11, 1943. Most of the 80 who began the mission, survived the war.

Thirteen targets were attacked, including an oil tank farm, a steel mill, and an aircraft carrier then under construction.. Fifty were killed and another 400 injured, but the mission had a decisive psychological effect. Japan withdrew its powerful aircraft carrier force to protect the home islands. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto attacked Midway, thinking it to have been the jump-off point for the raid. Described by military historian John Keegan as “the most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare”, the battle of Midway would be a major strategic defeat for Imperial Japan.

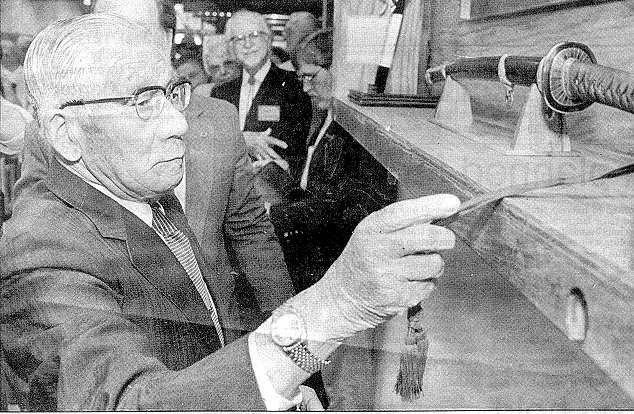

Every year since the late 1940s, the surviving Doolittle raiders have held a reunion. In 1959, the city of Tucson presented them with 80 silver goblets, each engraved with a name. They are on display at the National Museum of the Air Force, in Dayton Ohio.

With those goblets is a fine bottle of vintage Cognac. 1896, the year Jimmy Doolittle was born. There’s been a bargain among the survivors that, one day, the last two would open that bottle, and toast their comrades.

In 2013 they changed their bargain. Just a little. Jimmy Doolittle himself passed away in 1993. Twenty years later, 76 goblets had been turned over, each signifying a man who had passed on. Now, there were only four.

- Lieutenant Colonel Richard E. Cole* of Dayton Ohio was co-pilot of crew No. 1. Remained in China after the Tokyo Raid until June 1943, and served in the China-Burma-India Theater from October, 1943 until June, 1944. Relieved from active duty in January, 1947 but returned to active duty in August 1947.

- Lieutenant Colonel Robert L. Hite* of Odell Texas was co-pilot of crew No. 16. Captured by the Japanese and held prisoner for forty months, he watched his weight drop to eighty pounds.

- Lieutenant Colonel Edward J. Saylor* of Brusett Montana was engineer-gunner of crew No. 15. Served throughout the duration of WW2 until March 1945, both Stateside, and overseas. Accepted a commission in October 1947 and served as Aircraft Maintenance Officer at bases in Iowa, Washington, Labrador and England.

- Staff Sergeant David J. Thatcher* of Bridger Montana was engineer-gunner of crew No. 7. Served in England and Africa after the Tokyo raid until June 1944, and discharged in July 1945.

*H/T, http://www.doolittleraider.com

These four agreed that they would gather one last time. It would be these four men who would finally open that bottle.

Robert Hite, 93, was too frail to travel in 2013. Wally Hite, stood in for his father.

On November 9, 2013, a 117 year-old bottle of rare, vintage cognac was cracked open, and enjoyed among a company of heroes. If there is a more magnificent act of tribute, I cannot at this moment think of what it might be.

On April 18, 2015, Richard Cole and David Thatcher fulfilled their original bargain, as the last surviving members of the Doolittle raid. Staff Sergeant Thatcher passed away on June 23, 2016, at the age of 94. As I write this, only one of those eighty goblets remains upright. Lieutenant Colonel Richard Cole, co-pilot to mission leader Jimmy Doolittle himself, is 103. He is the only living man on the planet, who has earned the right to open that rare and vintage cognac.

Even before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Loyce had wanted to join the Navy. In October 1942, he did just that. First there was basic training in San Diego, and then gunner’s school, learning all about the weapons systems aboard a Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bomber. Then on to Naval Air School Fort Lauderdale, before joining the new 15th Air Group, forming out of Westerly, Rhode Island.

Even before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Loyce had wanted to join the Navy. In October 1942, he did just that. First there was basic training in San Diego, and then gunner’s school, learning all about the weapons systems aboard a Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bomber. Then on to Naval Air School Fort Lauderdale, before joining the new 15th Air Group, forming out of Westerly, Rhode Island. Loyce was the turret gunner on one of these Avengers, assigned to protect the aircraft from above and teamed up with Pilot Lt. Robert Cosgrove from New Orleans, Louisiana and Radioman Digby Denzek, from Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Loyce was the turret gunner on one of these Avengers, assigned to protect the aircraft from above and teamed up with Pilot Lt. Robert Cosgrove from New Orleans, Louisiana and Radioman Digby Denzek, from Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Which brings us back to that funny-looking boat. The Office of Strategic Services (OSS), predecessor to the modern Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), built two of these semi-submersibles, code named “Gimik”, part of a top-secret operation code named “NAPKO”.

Which brings us back to that funny-looking boat. The Office of Strategic Services (OSS), predecessor to the modern Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), built two of these semi-submersibles, code named “Gimik”, part of a top-secret operation code named “NAPKO”.

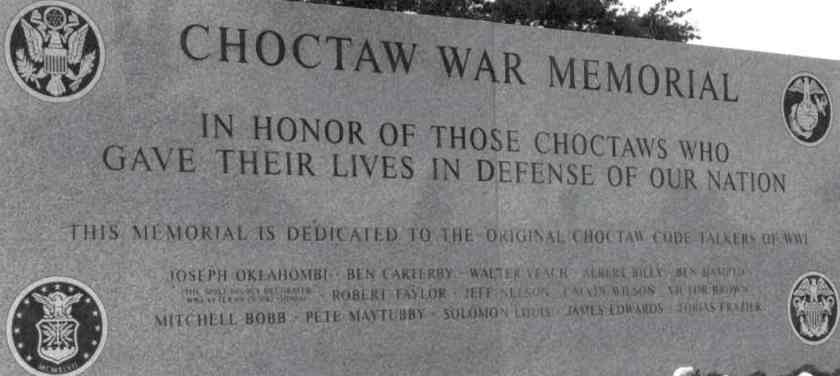

The history of the Navajo code talkers of WWII is relatively well known, but by no means, unique. Indigenous Americans of other nations served as code talkers in WW2, including Assiniboine, Lakota and Meskwaki soldiers, who did service in the Pacific, North African, and European theaters of the war.

The history of the Navajo code talkers of WWII is relatively well known, but by no means, unique. Indigenous Americans of other nations served as code talkers in WW2, including Assiniboine, Lakota and Meskwaki soldiers, who did service in the Pacific, North African, and European theaters of the war.

The Choctaw themselves didn’t use the term “Code Talker”, that wouldn’t come along until WWII. At least one member of the group, Tobias W. Frazier, simply described what they did as, “talking on the radio”. Of the 19 who served in WWI, 18 were native Choctaw from southeast Oklahoma. The last was a native Chickasaw. The youngest was Benjamin Franklin Colbert, Jr., the son of Benjamin Colbert Sr., one of Teddy Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders” of the Spanish American War. Born September 15, 1900 in the Durant Indian Territory, he was all of sixteen, the day he enlisted.

The Choctaw themselves didn’t use the term “Code Talker”, that wouldn’t come along until WWII. At least one member of the group, Tobias W. Frazier, simply described what they did as, “talking on the radio”. Of the 19 who served in WWI, 18 were native Choctaw from southeast Oklahoma. The last was a native Chickasaw. The youngest was Benjamin Franklin Colbert, Jr., the son of Benjamin Colbert Sr., one of Teddy Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders” of the Spanish American War. Born September 15, 1900 in the Durant Indian Territory, he was all of sixteen, the day he enlisted.

The harbor at Scapa flow had been home to the British deep water fleet since 1904, a time when the place truly was, all but impregnable. By 1939, anti-aircraft weaponry was all but obsolete, old block ships were disintegrating, and anti-submarine nets were inadequate to the needs of the new war.

The harbor at Scapa flow had been home to the British deep water fleet since 1904, a time when the place truly was, all but impregnable. By 1939, anti-aircraft weaponry was all but obsolete, old block ships were disintegrating, and anti-submarine nets were inadequate to the needs of the new war. The electric torpedoes of the era were highly unreliable, and this wasn’t shaping up to be their night.

The electric torpedoes of the era were highly unreliable, and this wasn’t shaping up to be their night.

The European allies and Imperial Germany had about 20,000 dogs working a variety of jobs in WWI. Though the United States didn’t have an official “War Dog” program in those days, a Staffordshire Terrier mix called “Sgt. Stubby” was smuggled “over there” with an AEF unit training out of New Haven, Connecticut.

The European allies and Imperial Germany had about 20,000 dogs working a variety of jobs in WWI. Though the United States didn’t have an official “War Dog” program in those days, a Staffordshire Terrier mix called “Sgt. Stubby” was smuggled “over there” with an AEF unit training out of New Haven, Connecticut.

Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and licking faces & performing tricks for thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s been called “the first published post-traumatic stress canine”, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed.

Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and licking faces & performing tricks for thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s been called “the first published post-traumatic stress canine”, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed. A memorial statue was unveiled on December 12 of that year, at the Australian War Memorial at the Queensland Wacol Animal Care Campus in Brisbane.

A memorial statue was unveiled on December 12 of that year, at the Australian War Memorial at the Queensland Wacol Animal Care Campus in Brisbane.

The first Sino-Japanese war of July 1894 – April 1895, was primarily fought over control of the Korean peninsula. The outcome was never in doubt, with the Japanese army and navy by this time patterned after those of the strongest military forces of the day.

The first Sino-Japanese war of July 1894 – April 1895, was primarily fought over control of the Korean peninsula. The outcome was never in doubt, with the Japanese army and navy by this time patterned after those of the strongest military forces of the day.

As Western historians tell the tale of WW2, the deadliest conflict in history began in September 1939, with the Nazi invasion of Poland. The United States joined the conflagration two years later, following the sneak attack on the American Naval anchorage at Pearl Harbor, by naval air forces of the Empire of Japan.

As Western historians tell the tale of WW2, the deadliest conflict in history began in September 1939, with the Nazi invasion of Poland. The United States joined the conflagration two years later, following the sneak attack on the American Naval anchorage at Pearl Harbor, by naval air forces of the Empire of Japan.

John Connell Freeborn was a pilot with the RAF, and a good one, too. Credited with 13½ enemy aircraft shot down, Freeborn flew more operational hours during the Battle of Britain, than any other pilot, ending the war with a Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar, and completing his RAF career as a Wing Commander. Yet, there is a time when every hero is as green as the grass. In the beginning, John Freeborn like everyone else, were rank amateurs.

John Connell Freeborn was a pilot with the RAF, and a good one, too. Credited with 13½ enemy aircraft shot down, Freeborn flew more operational hours during the Battle of Britain, than any other pilot, ending the war with a Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar, and completing his RAF career as a Wing Commander. Yet, there is a time when every hero is as green as the grass. In the beginning, John Freeborn like everyone else, were rank amateurs.

Richard Hough and Denis Richards wrote about the episode in

Richard Hough and Denis Richards wrote about the episode in

You must be logged in to post a comment.