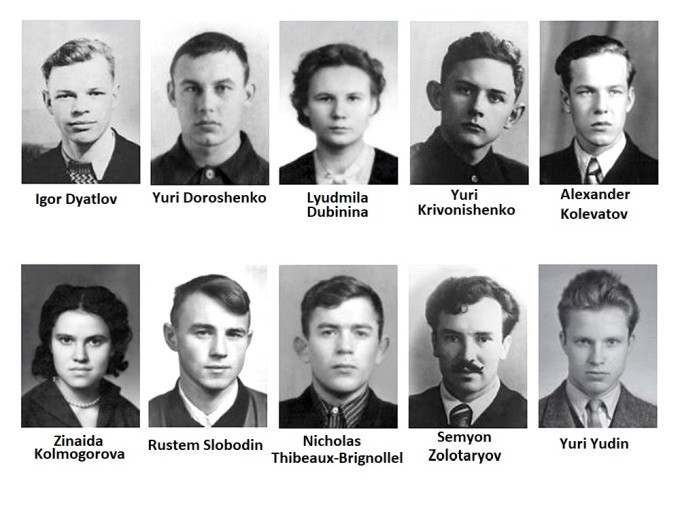

In the world of mountaineering, climbers assign a grade to a boulder or climbing route, describing the degree of difficulty and danger, in the ascent. The group assembled in January 1959 were experienced Grade II hikers, off on a winter trek which would earn them a Grade III certification, upon their safe return. They were ten in number, colleagues from the Ural Polytechnic Institute in Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg) Russia, bent on conquering Mount Otorten, in the northern Ural Mountains. The Northern Ural is a remote and frozen place, the Ural Mountains forming the barrier between the European and Asian continents and ending in an island chain, in the Arctic Ocean. Very few live there, mostly a small ethnic minority called the Mansi people.

The Northern Ural is a remote and frozen place, the Ural Mountains forming the barrier between the European and Asian continents and ending in an island chain, in the Arctic Ocean. Very few live there, mostly a small ethnic minority called the Mansi people.

In the Mansi tongue, Otorten translates as “Don’t Go There”.

No matter. This was going to be an adventure. The eight men and two women made it by truck as far as the tiny village of Vizhai, on the edge of the wilderness. There the group learned the ancient and not a little frightening tale of a group of Mansi hunters, mysteriously murdered on what came to be called “Dead Mountain”.

The eight men and two women made it by truck as far as the tiny village of Vizhai, on the edge of the wilderness. There the group learned the ancient and not a little frightening tale of a group of Mansi hunters, mysteriously murdered on what came to be called “Dead Mountain”.

Nothing like a good, scary mystery when you’re heading into the woods. Right? On January 28, Yuri Yudin became ill, and had to back out of the trek. The other nine agreed to carry on. None of them knew at the time. Yudin was about to become the sole survivor of a terrifying mystery.

On January 28, Yuri Yudin became ill, and had to back out of the trek. The other nine agreed to carry on. None of them knew at the time. Yudin was about to become the sole survivor of a terrifying mystery.

The leader of the expedition, Igor Dyatlov, left word that he expected to return, on February 12. The day came and went with no sign of the group but, no big deal. It was common enough to come back a few days late, from the frozen wilds of the Ural Mountains. By February 20. friends and relatives were concerned Something was wrong. Rescue expeditions were assembled, first from students and faculty of the Ural Polytechnic Institute and later by military and local police.

By February 20. friends and relatives were concerned Something was wrong. Rescue expeditions were assembled, first from students and faculty of the Ural Polytechnic Institute and later by military and local police.

There were airplanes and helicopters, and skiers on the ground. On February 26, searchers found an abandoned tent on the flanks of Kholat Syakhl. Dead Mountain.

Mikhail Sharavin, the student who found the tent, described the scene: “the tent was half torn down and covered with snow. It was empty, and all the group’s belongings and shoes had been left behind.” The tent was cut up the back from the inside, eight or nine sets of footprints in the snow, leading away some 1,600 feet until disappearing, under a fresh fall of snow.

Despite winter temperatures of -13° to -30° Fahrenheit, most of these prints showed feet clad only in socks. Some were barefoot. One had a single shoe. Two bodies were found clad only in underwear, those of Yuri (Georgiy) Krivonischenko and Yuri Doroshenko, near the remains of a small fire.

Their bodies were found under a large Siberian Pine, broken branches up to thirty feet suggesting that someone had climbed the thing, to look around. Or perhaps to get away? Three more bodies were found leading back to the tent, frozen in postures suggesting they were trying to return. Medical investigators examined the bodies. One, that of Rustem Slobodin showed a small skull fracture, probably not enough to threaten his life. Cause of death was ruled, hypothermia.

Three more bodies were found leading back to the tent, frozen in postures suggesting they were trying to return. Medical investigators examined the bodies. One, that of Rustem Slobodin showed a small skull fracture, probably not enough to threaten his life. Cause of death was ruled, hypothermia.

It took two more months to find the last four bodies, buried under twelve feet of snow some 75-feet away. These were better dressed than the other five, indicating they were already outside when something went wrong.  The condition of these last four, would change this whole story. There were unexplained traces of radiation on their clothes. The body of Nikolai Thibeaux-Brignolles showed massive skull fractures, with no external injury. Lyudmila Dubinina and Semyon (Alexander) Zolotaryov showed extensive chest fractures, as if hit by a car. Again, there were no external injuries. Both were missing their eyes. Dubinina was missing her tongue, and part of her face.

The condition of these last four, would change this whole story. There were unexplained traces of radiation on their clothes. The body of Nikolai Thibeaux-Brignolles showed massive skull fractures, with no external injury. Lyudmila Dubinina and Semyon (Alexander) Zolotaryov showed extensive chest fractures, as if hit by a car. Again, there were no external injuries. Both were missing their eyes. Dubinina was missing her tongue, and part of her face. With volumes of questions and no answers, the inquiry was closed in May, 1959. Cause of death was ruled “A spontaneous force which the hikers were unable to overcome“. Dead Mountain was ruled off limits, the files marked confidential. Case closed.

With volumes of questions and no answers, the inquiry was closed in May, 1959. Cause of death was ruled “A spontaneous force which the hikers were unable to overcome“. Dead Mountain was ruled off limits, the files marked confidential. Case closed.

“A spontaneous force which the hikers were unable to overcome“.

Explanations have been offered from the mundane to the supernatural, but none made sense. Mansi hunters had killed them for encroaching on their territory. Except, there were no other footprints. This was the work of a Menk, a mythical Siberian Yeti, or an avalanche, or a super-secret parachute mine exercise, carried out by the Soviet military. There were reports of orange glowing orbs, in the sky. Some believe it was aliens.

How nine experienced mountaineers got caught out in a frozen wilderness or why their tent was cut from the inside, remains a mystery. Missing eyes and tongues may be explained away by small animals. Maybe. The massive internal injuries suffered by three of the victims, defy explanation. The place where it all happened has come to be known as Dyatlov Pass. What happened in that place remains an enigma, to this day.

An estimated 4,000 to 93,000 died in the aftermath of the accident, many of whom, were children.

An estimated 4,000 to 93,000 died in the aftermath of the accident, many of whom, were children. Officials of the top-down Soviet state first downplayed the disaster. Asked by one Ukrainian official, “How are the people?“, acting minister of Internal Affairs Vasyl Durdynets replied there was nothing to be concerned about: “Some are celebrating a wedding, others are gardening, and others are fishing in the Pripyat River.”

Officials of the top-down Soviet state first downplayed the disaster. Asked by one Ukrainian official, “How are the people?“, acting minister of Internal Affairs Vasyl Durdynets replied there was nothing to be concerned about: “Some are celebrating a wedding, others are gardening, and others are fishing in the Pripyat River.” The chaos of these forced evacuations, can scarcely be imagined. Confused adults. Crying children. Howling dogs. Shouting soldiers, barking orders and herding now-homeless civilians onto waiting trains and vehicles by the tens of thousands. Dogs and cats, beloved companion animals and lifelong family members, were abandoned to fend for themselves.

The chaos of these forced evacuations, can scarcely be imagined. Confused adults. Crying children. Howling dogs. Shouting soldiers, barking orders and herding now-homeless civilians onto waiting trains and vehicles by the tens of thousands. Dogs and cats, beloved companion animals and lifelong family members, were abandoned to fend for themselves. There were countless and heartbreaking scenes of final abandonment, of mewling cats, and whimpering dogs. Belorussian writer Svetlana Alexievich compiled hundreds of interviews into a single monologue, an oral history of the forgotten. The devastating Chernobyl Prayer tells the story of: “dogs howling, trying to get on the buses. Mongrels, Alsatians. The soldiers were pushing them out again, kicking them. They ran after the buses for ages.”

There were countless and heartbreaking scenes of final abandonment, of mewling cats, and whimpering dogs. Belorussian writer Svetlana Alexievich compiled hundreds of interviews into a single monologue, an oral history of the forgotten. The devastating Chernobyl Prayer tells the story of: “dogs howling, trying to get on the buses. Mongrels, Alsatians. The soldiers were pushing them out again, kicking them. They ran after the buses for ages.”  There was no mercy. Squads of soldiers were sent to shoot the animals, left behind. Heartbroken families pinned notes to their doors: “Don’t kill our Zhulka. She’s a good dog.” Most of these abandoned pets, were shot. Some escaped notice, and survived.

There was no mercy. Squads of soldiers were sent to shoot the animals, left behind. Heartbroken families pinned notes to their doors: “Don’t kill our Zhulka. She’s a good dog.” Most of these abandoned pets, were shot. Some escaped notice, and survived. Later on, plant management hired someone, to kill the 1,000 or so dogs still remaining. The story is, the worker refused.

Later on, plant management hired someone, to kill the 1,000 or so dogs still remaining. The story is, the worker refused. Today, untold numbers of stray dogs live in the towns of Chernobyl, Pripyat and surrounding villages. Descendants of those left behind, back in 1986. Ill equipped to survive in the wild and driven from forests by wolves and other predators, they forage as best they can among abandoned streets and buildings, of the 1,000-mile exclusion zone. For some, radiation can be found in their fur. Few live beyond the age of six but, all is not bleak.

Today, untold numbers of stray dogs live in the towns of Chernobyl, Pripyat and surrounding villages. Descendants of those left behind, back in 1986. Ill equipped to survive in the wild and driven from forests by wolves and other predators, they forage as best they can among abandoned streets and buildings, of the 1,000-mile exclusion zone. For some, radiation can be found in their fur. Few live beyond the age of six but, all is not bleak. Since September 2017, a partnership between the SPCA International and the US-based 501(c)(3) non-profit

Since September 2017, a partnership between the SPCA International and the US-based 501(c)(3) non-profit  Some have been successfully decontaminated and socialized for human interaction. In 2018, the first batch became available for adoption into homes in Ukraine and North America, some forty puppies and dogs.

Some have been successfully decontaminated and socialized for human interaction. In 2018, the first batch became available for adoption into homes in Ukraine and North America, some forty puppies and dogs. Believe it or not there are visitors to the area. People actually go on tours of the region but they’re strictly warned. No matter how adorable, do not pet, cuddle nor even touch any puppy or dog who has not been through rigorous decontamination.

Believe it or not there are visitors to the area. People actually go on tours of the region but they’re strictly warned. No matter how adorable, do not pet, cuddle nor even touch any puppy or dog who has not been through rigorous decontamination.

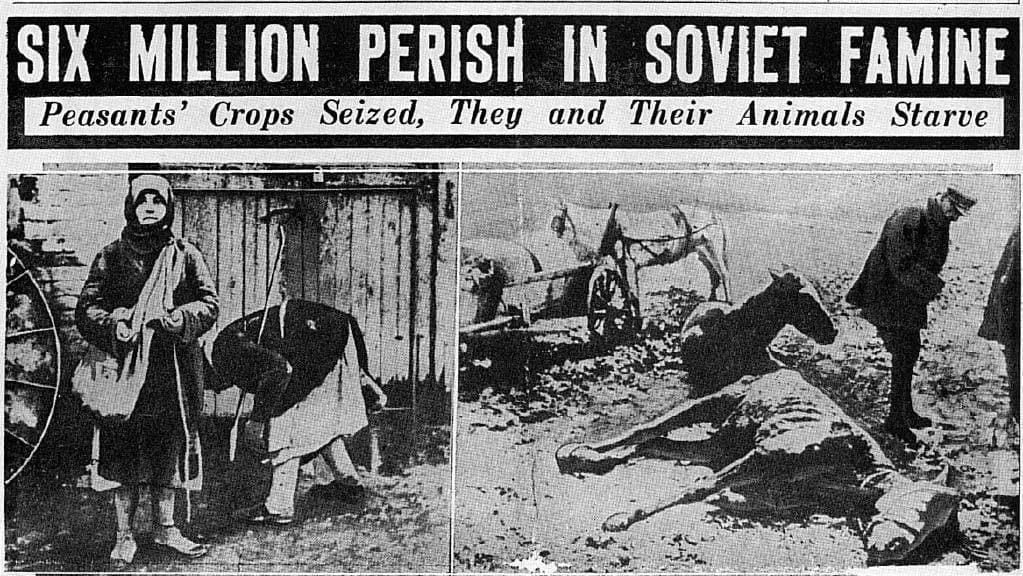

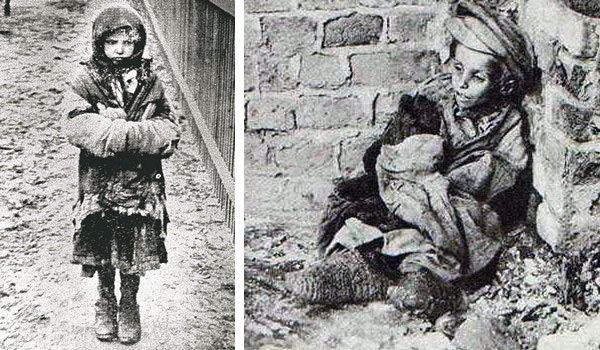

Armed dekulakization brigades confiscated land, livestock and other property by force, evicting entire families. Nearly half a million individuals were dragged from their homes in 1930-’31 alone, packed into freight trains and shipped off to remote areas like Siberia and often left without food or shelter. Many of them, especially children, died in transit or soon after arrival.

Armed dekulakization brigades confiscated land, livestock and other property by force, evicting entire families. Nearly half a million individuals were dragged from their homes in 1930-’31 alone, packed into freight trains and shipped off to remote areas like Siberia and often left without food or shelter. Many of them, especially children, died in transit or soon after arrival. Military blockades were erected around villages preventing the transportation of food, while brigades of young activists from other regions were brought in to sweep through villages and confiscate hidden grain.

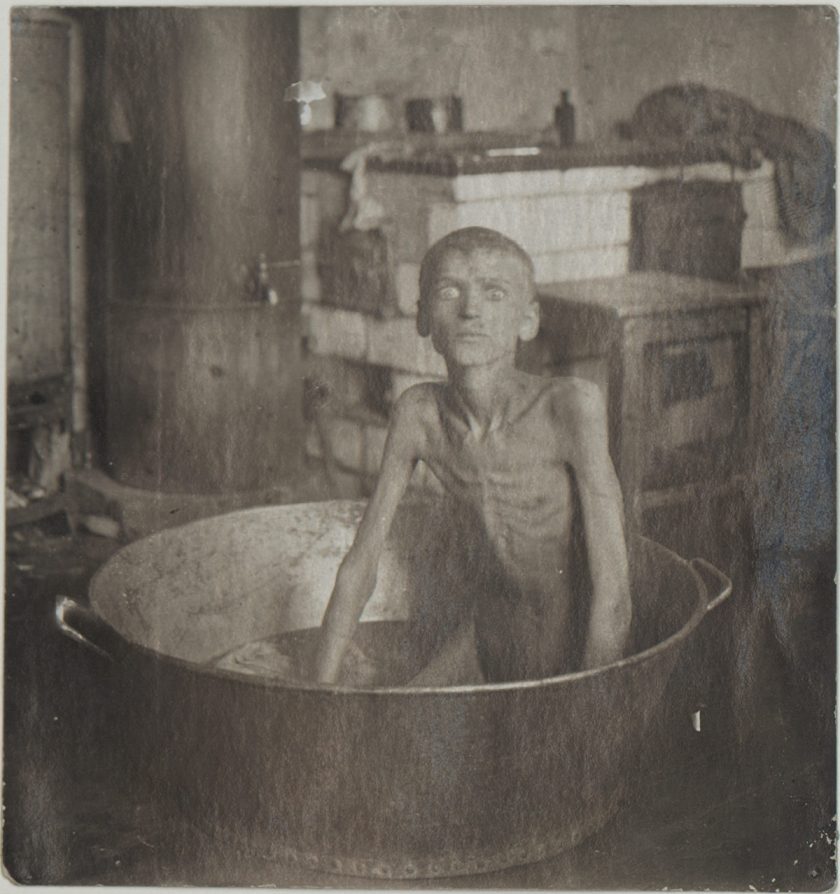

Military blockades were erected around villages preventing the transportation of food, while brigades of young activists from other regions were brought in to sweep through villages and confiscate hidden grain. At the height of the famine, Ukrainians starved to death at a rate of 22,000 per day, almost a third of those, children 10 and under. How many died in total, is anyone’s guess. Estimates range from two million Ukrainian citizens murdered by their own government, to well over ten million.

At the height of the famine, Ukrainians starved to death at a rate of 22,000 per day, almost a third of those, children 10 and under. How many died in total, is anyone’s guess. Estimates range from two million Ukrainian citizens murdered by their own government, to well over ten million. 2,500 people were arrested and convicted during this time, for eating the flesh of their neighbors. The problem was so widespread that the Soviet government put up signs reminding survivors: “To eat your own children is a barbarian act.”

2,500 people were arrested and convicted during this time, for eating the flesh of their neighbors. The problem was so widespread that the Soviet government put up signs reminding survivors: “To eat your own children is a barbarian act.” To this day, the New York Times has failed to repudiate Walter Duranty’s Pulitzer.

To this day, the New York Times has failed to repudiate Walter Duranty’s Pulitzer. To do so at all was an act of courage. single Jewish woman who’d lost part of a leg in a childhood streetcar accident, traveling to a place where the Russian empire and its successor state had a long and wretched history. Particularly when it came to the treatment of its own Jews.

To do so at all was an act of courage. single Jewish woman who’d lost part of a leg in a childhood streetcar accident, traveling to a place where the Russian empire and its successor state had a long and wretched history. Particularly when it came to the treatment of its own Jews.

The Holodomor Memorial to Victims of the Ukrainian Famine-Genocide of 1932–1933 was opened in Washington, D.C. on November 7, 2015

The Holodomor Memorial to Victims of the Ukrainian Famine-Genocide of 1932–1933 was opened in Washington, D.C. on November 7, 2015

Taken individually, either power possessed the potential to destroy the world order. The mind can only ponder the great good fortune of we who would be free, that these malign governments turned to destroying each other.

Taken individually, either power possessed the potential to destroy the world order. The mind can only ponder the great good fortune of we who would be free, that these malign governments turned to destroying each other.

Gagarin’s flight gave fresh life to the “Space Race” between the cold war rivals. President John F. Kennedy announced the intention to put a man on the moon, before the end of the decade.

Gagarin’s flight gave fresh life to the “Space Race” between the cold war rivals. President John F. Kennedy announced the intention to put a man on the moon, before the end of the decade.

The accident began as a test, a carefully planned series of events, intending to simulate a station blackout at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, in the Soviet Socialist Republic of Ukraine.

The accident began as a test, a carefully planned series of events, intending to simulate a station blackout at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, in the Soviet Socialist Republic of Ukraine.

A tall, bearded peasant was spokesman. His two sons and the rest of the men and women nodded approval at every word. The little crippled boy stood with his right hand on his crutch, translating everything he said into Russian for me, word by word.

A tall, bearded peasant was spokesman. His two sons and the rest of the men and women nodded approval at every word. The little crippled boy stood with his right hand on his crutch, translating everything he said into Russian for me, word by word.

As Stalin’s Soviet Union imposed the “terror famine” of 1932-’33, the deliberate starvation of millions of Ukrainian peasant farmers known as the

As Stalin’s Soviet Union imposed the “terror famine” of 1932-’33, the deliberate starvation of millions of Ukrainian peasant farmers known as the  As director of the Soviet Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Lysenko put his theories to work, with unsurprisingly dismal results. He’d force Soviet farmers to plant WAY too close together, on the theory that plants of the same “class” would “cooperate” with one another, and that “mutual assistance” takes place within and even across plant species.

As director of the Soviet Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Lysenko put his theories to work, with unsurprisingly dismal results. He’d force Soviet farmers to plant WAY too close together, on the theory that plants of the same “class” would “cooperate” with one another, and that “mutual assistance” takes place within and even across plant species.

By the siege’s end in the Spring of 1944, nine of them had starved to death, standing watch over all that food. These guys had stood guard over their seed bank for twenty-eight months, without eating so much as a grain.

By the siege’s end in the Spring of 1944, nine of them had starved to death, standing watch over all that food. These guys had stood guard over their seed bank for twenty-eight months, without eating so much as a grain.

On the morning of June 30, 1908, the Tunguska River lit up with a bluish-white light. At 7:17a local time, a column of light far too bright to look at moved across the skies above the Tunguska. Minutes later, a vast explosion knocked people off their feet, flattening buildings, crops and as many as 80 million trees over an area of 830-square miles. A vast “thump” was heard, the shock wave equivalent to an earthquake measuring 5.0 on the Richter scale. Within minutes came a second and then a third shock wave and finally a fourth, more distant this time and described by eyewitnesses as the “sun going to sleep”.

On the morning of June 30, 1908, the Tunguska River lit up with a bluish-white light. At 7:17a local time, a column of light far too bright to look at moved across the skies above the Tunguska. Minutes later, a vast explosion knocked people off their feet, flattening buildings, crops and as many as 80 million trees over an area of 830-square miles. A vast “thump” was heard, the shock wave equivalent to an earthquake measuring 5.0 on the Richter scale. Within minutes came a second and then a third shock wave and finally a fourth, more distant this time and described by eyewitnesses as the “sun going to sleep”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.