On November 9, 2013, there occurred a gathering of four. A tribute to fallen heroes. These four were themselves heroes, and worthy of tribute. This was to be their last such gathering.

This story begins on April 18, 1942, when a flight of sixteen Mitchell B25 medium bombers took off from the deck of the carrier, USS Hornet. It was a retaliatory raid on Imperial Japan, planned and led by Lieutenant Colonel James “Jimmy” Doolittle of the United States Army Air Forces. It was payback for the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, seven months earlier. A demonstration that the Japanese home islands, were not immune from destruction.

Launching such massive aircraft from the decks of a carrier had never been attempted, and there were no means of bringing them back. With extra gas tanks installed and machine guns removed to save the weight, this was to be a one-way mission, into territory occupied by a savage adversary.

Fearing that mission security had been breached, the bomb run was forced to launch 200 miles before the intended departure spot. The range made fighter escort impossible, and left the bombers themselves with only the slimmest margin of error.

Japanese Premier Hideki Tojo was inspecting military bases, at the time of the raid. One B-25 came so close he could see the pilot, though the American bomber never fired a shot.

After dropping their bombs, fifteen continued west, toward Japanese occupied China. Unbeknownst at the time, carburetors bench-marked and calibrated for low level flight had been replaced in flight #8, which now had no chance of making it to the mainland. Twelve crash landed in the coastal provinces. Three more, ditched at sea. Pilot Captain Edward York pointed flight 8 toward Vladivostok, where he hoped to refuel. The pilot and crew were instead taken into captivity, and held for thirteen months.

Crew 3 Engineer-Gunner Corporal Leland Dale Faktor died in the fall after bailing out and Staff Sergeant Bombardier William Dieter and Sergeant Engineer-Gunner Donald Fitzmaurice bailed out of aircraft # 6 off the China coast, and drowned.

The heroism of the indigenous people at this point, is a little-known part of this story. The massive sweep across the eastern coastal provinces, the Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign, cost the lives of 250,000 Chinese. A quarter-million murdered by Japanese soldiers, in the hunt for Doolittle’s raiders. How many could have betrayed the Americans and refused, will never be known.

Amazingly, only eight were captured, among the seventy-seven survivors.

First Lieutenant Pilot “Bill” Farrow and Sergeant Engineer-Gunner Harold Spatz, both of Crew 16, and First Lieutenant Pilot Dean Edward Hallmark of Crew 6 were caught by the Japanese and executed by firing squad on October 15, 1942. Crew 6 Co-Pilot First Lieutenant Robert John Meder died in a Japanese prison camp, on December 11, 1943. Most of the 80 who began the mission, survived the war.

Thirteen targets were attacked, including an oil tank farm, a steel mill, and an aircraft carrier then under construction.. Fifty were killed and another 400 injured, but the mission had a decisive psychological effect. Japan withdrew its powerful aircraft carrier force to protect the home islands. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto attacked Midway, thinking it to have been the jump-off point for the raid. Described by military historian John Keegan as “the most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare”, the battle of Midway would be a major strategic defeat for Imperial Japan.

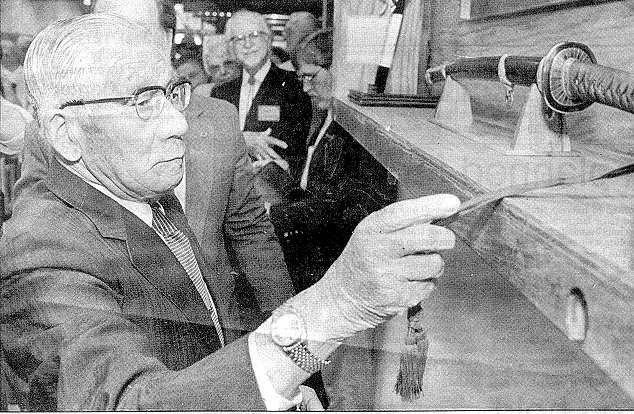

Every year since the late 1940s, the surviving Doolittle raiders have held a reunion. In 1959, the city of Tucson presented them with 80 silver goblets, each engraved with a name. They are on display at the National Museum of the Air Force, in Dayton Ohio.

With those goblets is a fine bottle of vintage Cognac. 1896, the year Jimmy Doolittle was born. There’s been a bargain among the survivors that, one day, the last two would open that bottle, and toast their comrades.

In 2013 they changed their bargain. Just a little. Jimmy Doolittle himself passed away in 1993. Twenty years later, 76 goblets had been turned over, each signifying a man who had passed on. Now, there were only four.

- Lieutenant Colonel Richard E. Cole* of Dayton Ohio was co-pilot of crew No. 1. Remained in China after the Tokyo Raid until June 1943, and served in the China-Burma-India Theater from October, 1943 until June, 1944. Relieved from active duty in January, 1947 but returned to active duty in August 1947.

- Lieutenant Colonel Robert L. Hite* of Odell Texas was co-pilot of crew No. 16. Captured by the Japanese and held prisoner for forty months, he watched his weight drop to eighty pounds.

- Lieutenant Colonel Edward J. Saylor* of Brusett Montana was engineer-gunner of crew No. 15. Served throughout the duration of WW2 until March 1945, both Stateside, and overseas. Accepted a commission in October 1947 and served as Aircraft Maintenance Officer at bases in Iowa, Washington, Labrador and England.

- Staff Sergeant David J. Thatcher* of Bridger Montana was engineer-gunner of crew No. 7. Served in England and Africa after the Tokyo raid until June 1944, and discharged in July 1945.

*H/T, http://www.doolittleraider.com

These four agreed that they would gather one last time. It would be these four men who would finally open that bottle.

Robert Hite, 93, was too frail to travel in 2013. Wally Hite, stood in for his father.

On November 9, 2013, a 117 year-old bottle of rare, vintage cognac was cracked open, and enjoyed among a company of heroes. If there is a more magnificent act of tribute, I cannot at this moment think of what it might be.

On April 18, 2015, Richard Cole and David Thatcher fulfilled their original bargain, as the last surviving members of the Doolittle raid. Staff Sergeant Thatcher passed away on June 23, 2016, at the age of 94. As I write this, only one of those eighty goblets remains upright. Lieutenant Colonel Richard Cole, co-pilot to mission leader Jimmy Doolittle himself, is 103. He is the only living man on the planet, who has earned the right to open that rare and vintage cognac.

Even before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Loyce had wanted to join the Navy. In October 1942, he did just that. First there was basic training in San Diego, and then gunner’s school, learning all about the weapons systems aboard a Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bomber. Then on to Naval Air School Fort Lauderdale, before joining the new 15th Air Group, forming out of Westerly, Rhode Island.

Even before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Loyce had wanted to join the Navy. In October 1942, he did just that. First there was basic training in San Diego, and then gunner’s school, learning all about the weapons systems aboard a Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bomber. Then on to Naval Air School Fort Lauderdale, before joining the new 15th Air Group, forming out of Westerly, Rhode Island. Loyce was the turret gunner on one of these Avengers, assigned to protect the aircraft from above and teamed up with Pilot Lt. Robert Cosgrove from New Orleans, Louisiana and Radioman Digby Denzek, from Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Loyce was the turret gunner on one of these Avengers, assigned to protect the aircraft from above and teamed up with Pilot Lt. Robert Cosgrove from New Orleans, Louisiana and Radioman Digby Denzek, from Grand Rapids, Michigan.

For Frank Eugene Corder, life took a turn for the worse in 1993, around the time the truck driver was fired for reasons unknown. That April, Corder was arrested for theft. Another arrest that October, this time on illegal substance charges, led to a 90-day sentence to a drug rehab center.

For Frank Eugene Corder, life took a turn for the worse in 1993, around the time the truck driver was fired for reasons unknown. That April, Corder was arrested for theft. Another arrest that October, this time on illegal substance charges, led to a 90-day sentence to a drug rehab center.

John Connell Freeborn was a pilot with the RAF, and a good one, too. Credited with 13½ enemy aircraft shot down, Freeborn flew more operational hours during the Battle of Britain, than any other pilot, ending the war with a Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar, and completing his RAF career as a Wing Commander. Yet, there is a time when every hero is as green as the grass. In the beginning, John Freeborn like everyone else, were rank amateurs.

John Connell Freeborn was a pilot with the RAF, and a good one, too. Credited with 13½ enemy aircraft shot down, Freeborn flew more operational hours during the Battle of Britain, than any other pilot, ending the war with a Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar, and completing his RAF career as a Wing Commander. Yet, there is a time when every hero is as green as the grass. In the beginning, John Freeborn like everyone else, were rank amateurs.

Richard Hough and Denis Richards wrote about the episode in

Richard Hough and Denis Richards wrote about the episode in

There would be 5 hours of unarmed, unescorted flight through Nazi-controlled air space and an emergency landing with no brakes, before those V2 rocket components finally made it to England.

There would be 5 hours of unarmed, unescorted flight through Nazi-controlled air space and an emergency landing with no brakes, before those V2 rocket components finally made it to England.

The first non-stop transatlantic flight in history began on June 14, 1919, when British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown departed St. John’s, Newfoundland in a modified bomber, arriving in Ireland the following day.

The first non-stop transatlantic flight in history began on June 14, 1919, when British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown departed St. John’s, Newfoundland in a modified bomber, arriving in Ireland the following day. Five years later, “Lady Lindy” disappeared over the South Pacific, along with copilot Frederick J. Noonan.

Five years later, “Lady Lindy” disappeared over the South Pacific, along with copilot Frederick J. Noonan.

Corrigan made additional modifications and repeated applications over the next two years, all of which were rejected. By 1935, the once-freelance aviation industry faced increasing government regulation. Corrigan found his project losing ground. . In 1937, federal officials not only rebuffed his flight plan. Authorities deemed Corrigan’s aircraft Sunshine unstable for safe flight, and denied renewal of its license to fly.

Corrigan made additional modifications and repeated applications over the next two years, all of which were rejected. By 1935, the once-freelance aviation industry faced increasing government regulation. Corrigan found his project losing ground. . In 1937, federal officials not only rebuffed his flight plan. Authorities deemed Corrigan’s aircraft Sunshine unstable for safe flight, and denied renewal of its license to fly. Aviation officials were apoplectic that a New York to California flight plan, would wind up in Ireland. At a time when Western Union charged by the word, the pilot was excoriated with a 600-word diatribe, enumerating the pilot’s transgressions. Corrigan served a 14-day suspension of his flying license, ending the day he returned with his aircraft aboard the steamship Manhattan.

Aviation officials were apoplectic that a New York to California flight plan, would wind up in Ireland. At a time when Western Union charged by the word, the pilot was excoriated with a 600-word diatribe, enumerating the pilot’s transgressions. Corrigan served a 14-day suspension of his flying license, ending the day he returned with his aircraft aboard the steamship Manhattan. Wrong Way Corrigan flight tested bombers during WW2 and retired in 1950, and bought an orange grove in Santa Ana, California. He claimed he knew nothing about growing oranges, he just copied what his neighbors were doing.

Wrong Way Corrigan flight tested bombers during WW2 and retired in 1950, and bought an orange grove in Santa Ana, California. He claimed he knew nothing about growing oranges, he just copied what his neighbors were doing.

With sandbags, explosives, and the device which made the thing work, the total payload was about a thousand pounds on liftoff. The first such device was released on November 3, 1944, beginning the crossing to the west coast of North America. 9,300 such balloons were released with military payloads, between late 1944 and April, 1945.

With sandbags, explosives, and the device which made the thing work, the total payload was about a thousand pounds on liftoff. The first such device was released on November 3, 1944, beginning the crossing to the west coast of North America. 9,300 such balloons were released with military payloads, between late 1944 and April, 1945. In 1945, intercontinental weapons were more in the realm of science fiction. As these devices began to appear, American authorities theorized that they originated with submarine-based beach assaults, German POW camps, and even the internment camps into which the Roosevelt administration herded Japanese Americans.

In 1945, intercontinental weapons were more in the realm of science fiction. As these devices began to appear, American authorities theorized that they originated with submarine-based beach assaults, German POW camps, and even the internment camps into which the Roosevelt administration herded Japanese Americans.

American authorities were alarmed. Anti-personnel and incendiary bombs were relatively low grade threats. Not so the biological weapons Japanese military authorities were known to be developing at the infamous Unit 731, in northern China.

American authorities were alarmed. Anti-personnel and incendiary bombs were relatively low grade threats. Not so the biological weapons Japanese military authorities were known to be developing at the infamous Unit 731, in northern China.

Following four months of training, Richtofen began his flying career as an observer, taking photographs of Russian troop positions on the eastern front.

Following four months of training, Richtofen began his flying career as an observer, taking photographs of Russian troop positions on the eastern front. Ever aware of his own celebrity, von Richtofen took to painting the wings of his aircraft a brilliant shade of red, after the colors of his old Uhlan regiment. It was only later that he had the whole thing painted. Friend and foe alike knew him as “the Red Knight”, “the Red Devil”, or “’Le Petit Rouge’” and finally, the name that stuck: “the Red Baron”.

Ever aware of his own celebrity, von Richtofen took to painting the wings of his aircraft a brilliant shade of red, after the colors of his old Uhlan regiment. It was only later that he had the whole thing painted. Friend and foe alike knew him as “the Red Knight”, “the Red Devil”, or “’Le Petit Rouge’” and finally, the name that stuck: “the Red Baron”.

The RAF credited Canadian Pilot Captain Roy Brown with shooting Richthofen down, but the angle of the wound suggests that the bullet was fired from the ground. A 2003 PBS documentary demonstrated that Sergeant Cedric Popkin was the person most likely to have killed him, while a 2002 Discovery Channel documentary suggests that it was Gunner W. J. “Snowy” Evans, a Lewis machine gunner with the 53rd Battery, 14th Field Artillery Brigade, Royal Australian Artillery. Just who killed the Red Baron, may never be known with absolute certainty.

The RAF credited Canadian Pilot Captain Roy Brown with shooting Richthofen down, but the angle of the wound suggests that the bullet was fired from the ground. A 2003 PBS documentary demonstrated that Sergeant Cedric Popkin was the person most likely to have killed him, while a 2002 Discovery Channel documentary suggests that it was Gunner W. J. “Snowy” Evans, a Lewis machine gunner with the 53rd Battery, 14th Field Artillery Brigade, Royal Australian Artillery. Just who killed the Red Baron, may never be known with absolute certainty.

You must be logged in to post a comment.