For a variety of reasons, the eastern front of the “War to end all Wars” was a war of movement. Not so on the Western front. As early as October 1914, combatants were forced to burrow into the ground like animals, sheltering from what Ernst Jünger called the ‘Storm of Steel’.

Conditions in the trenches and dugouts must have defied description. You would have smelled the trenches long before you could see them. The collective funk of a million men and more, enduring the Troglodyte existence of men who live in holes. Little but verminous scars in the earth teaming with rats and lice and swarming with flies, time and again the shells churned up and pulverized the soil, the water and the shattered remnants of once-great forests, along with the bodies of the slain.

By the time the United States entered the ‘War to end all Wars’ in April, 1917, millions had endured this existence for three years. The first 14,000 Americans arrived ‘over there’ in June, the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) forming on July 5. American troops fought the military forces of Imperial Germany alongside their British and French allies, others joining Italian forces in the struggle against the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

You couldn’t call the stuff these people lived in mud – it was more like a thick slime, a clinging, sucking ooze capable of swallowing grown men, even horses and mules, alive.

Captain Alexander Stewart wrote “Most of the night was spent digging men out of the mud. The only way was to put duck boards on each side of him and work at one leg: poking and pulling until the suction was relieved. Then a strong pull by three or four men would get one leg out, and work would begin on the other…He who had a corpse to stand or sit on, was lucky”.

On first seeing the horror of Paschendaele, Sir Launcelot Kiggell broke down in tears. “Good God”, he said. “Did we really send men to fight in That?”

Often unseen in times of such dread calamity, are the humanitarian workers. Those who tend to the physical and spiritual requirements, the countless small comforts, of those so afflicted.

Often unseen in times of such dread calamity, are the humanitarian workers. Those who tend to the physical and spiritual requirements, the countless small comforts, of those so afflicted.

Within days of the American declaration of war, Evangeline Booth, National Commander of the Salvation Army, responded, saying “The Salvationist stands ready, trained in all necessary qualifications in every phase of humanitarian work, and the last man will stand by the President for execution of his orders”.

These people are so much more than that donation truck, and the bell ringers we see behind those red kettles, every December.

Lieutenant Colonel William S. Barker of the Salvation Army left New York with Adjutant Bertram Rodda on June 30, 1917, to survey the situation. It wasn’t long before his not-so surprising request came back in a cable from France. Send ‘Lassies’.

A small group of carefully selected female officers was sent to France on August 22. That first party comprised six men, three women and a married couple. Within fifteen months their number had expanded by a factor of 400.

A small group of carefully selected female officers was sent to France on August 22. That first party comprised six men, three women and a married couple. Within fifteen months their number had expanded by a factor of 400.

In December 1917, a plea for a million dollars went out to support the humanitarian work of the Salvation Army, the YMCA, YWCA, War Camp Community Service, National Catholic War Council, Jewish Welfare Board, the American Library Association and others. This “United War Work Campaign” raised $170 million in private donations, equivalent to $27.6 billion, today.

‘Hutments’ were formed all over the front, many right out at the front lines. There were canteen services. Religious observances of all denominations were held in these facilities. Concert performances were given, clothing mended and words of kindness offered in response to all manner of personal problems. On one occasion, the Loyal Order of Moose conducted a member initiation. Pies and cakes were baked in crude ovens and lemonade served to hot and thirsty troops. Of all these corporal works of mercy, the ones best remembered by the ‘doughboys’ themselves, were the doughnuts.

‘Hutments’ were formed all over the front, many right out at the front lines. There were canteen services. Religious observances of all denominations were held in these facilities. Concert performances were given, clothing mended and words of kindness offered in response to all manner of personal problems. On one occasion, the Loyal Order of Moose conducted a member initiation. Pies and cakes were baked in crude ovens and lemonade served to hot and thirsty troops. Of all these corporal works of mercy, the ones best remembered by the ‘doughboys’ themselves, were the doughnuts.

Helen Purviance, sent to France in 1917 with the American 1st Division, seems to have been first with the idea. An ensign with the Salvation Army, Purviance and fellow ensign Margaret Sheldon first formed the dough by hand, later using a wine bottle in lieu of a rolling pin. Having no doughnut cutter at the time, dough was shaped and twisted into crullers, and fried seven at a time on a pot-bellied wood stove.

The work was grueling. The women worked well into the night that first day, serving all of 150 hand-made doughnuts. “I was literally on my knees,” Purviance recalled, but it was easier than bending down all day, on that tiny wood stove. It didn’t seem to matter. Men stood in line for hours, patiently waiting in the mud and the rain for their own little piece of warm, home-cooked heaven in a world full of misery.

Before long, the women got better at it. Soon they were turning out 2,500 to 9,000 doughnuts a day. An elderly French blacksmith made Purviance a doughnut cutter, out of a condensed milk can and a camphor-ice tube, attached to a wooden block.

Before long, the women got better at it. Soon they were turning out 2,500 to 9,000 doughnuts a day. An elderly French blacksmith made Purviance a doughnut cutter, out of a condensed milk can and a camphor-ice tube, attached to a wooden block.

It wasn’t long before the aroma of hot doughnuts could be found, wafting all over the dugouts and trenches of the western front. Salvation Army volunteers and others made apple pies and all manner of other goodies, but the name that stuck, was “Doughnut Lassies”.

One New York Times correspondent wrote in 1918 “When I landed in France I didn’t think so much of the Salvation Army; after two weeks with the Americans at the front I take my hat off… [W]hen the memoirs of this war come to be written the doughnuts and apple pies of the Salvation Army are going to take their place in history”.

Fritz Duquesne was in charge of moving one of those shipments across the bushveld of Portuguese East Africa, when some kind of argument broke out. When it was over, only two wounded Boers were left alive, along with Duquesne himself and a few tottys (native porters). Duquesne ordered the tottys to hide the gold, burn the wagons and kill the survivors. He then rode off on an ox, having given the rest to the porters.

Fritz Duquesne was in charge of moving one of those shipments across the bushveld of Portuguese East Africa, when some kind of argument broke out. When it was over, only two wounded Boers were left alive, along with Duquesne himself and a few tottys (native porters). Duquesne ordered the tottys to hide the gold, burn the wagons and kill the survivors. He then rode off on an ox, having given the rest to the porters.

To keep costs down, off-the-shelf components were used whenever possible. The body was made of fiberglass to keep tooling expenses low. The chassis and suspension came from the 1952 Chevy sedan. The car featured an increased compression-ration version of the same in-line six “Blue Flame” block used in other models, coupled with a two-speed Power glide automatic transmission. No manual transmission of the time could reliably handle an output of 150 HP and a 0-60 time of 11½ seconds.

To keep costs down, off-the-shelf components were used whenever possible. The body was made of fiberglass to keep tooling expenses low. The chassis and suspension came from the 1952 Chevy sedan. The car featured an increased compression-ration version of the same in-line six “Blue Flame” block used in other models, coupled with a two-speed Power glide automatic transmission. No manual transmission of the time could reliably handle an output of 150 HP and a 0-60 time of 11½ seconds.

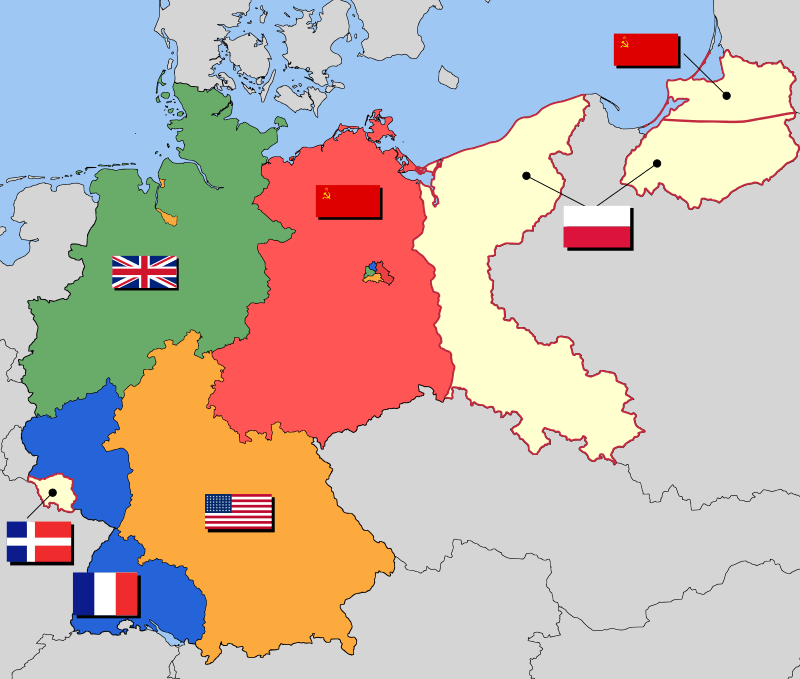

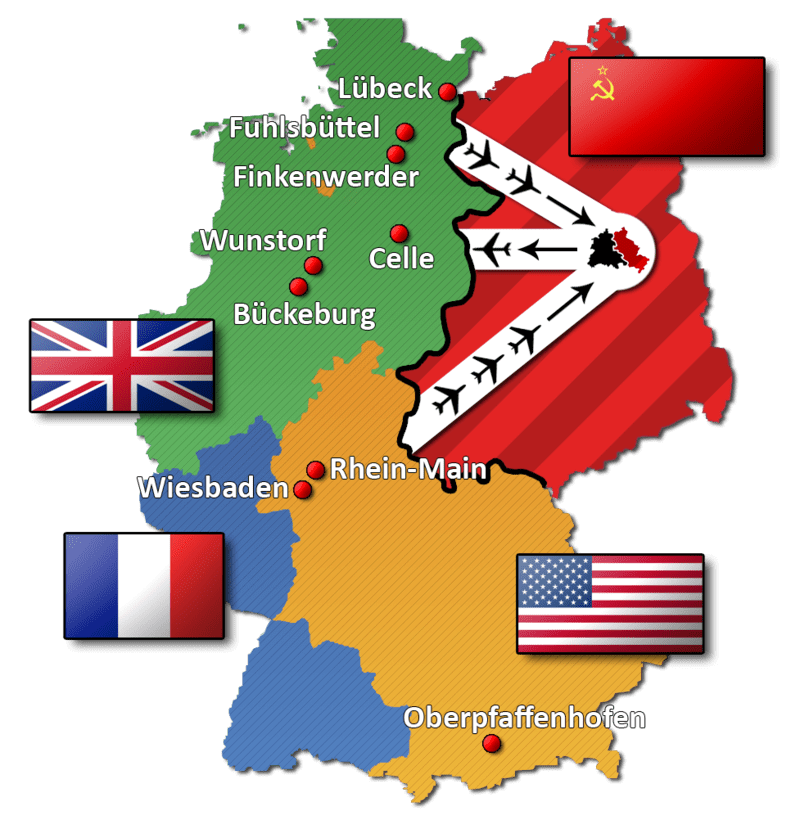

There never was any formal agreement, concerning road and rail access to Berlin through the 100-mile Soviet zone. Western leaders were forced to rely on the “good will” of a regime which had deliberately starved millions of its own citizens to death, in consolidating power.

There never was any formal agreement, concerning road and rail access to Berlin through the 100-mile Soviet zone. Western leaders were forced to rely on the “good will” of a regime which had deliberately starved millions of its own citizens to death, in consolidating power.

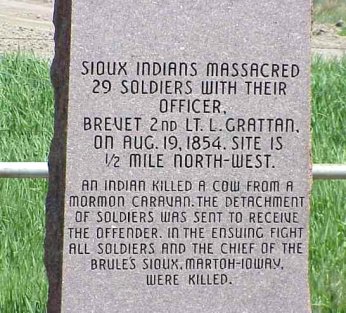

Chief Conquering Bear attempted to negotiate recompense, offering a horse or cow from the tribe’s herd. The owner refused, demanding $25. That same treaty of 1851 specified that such matters would be handled by the local Indian agent, in this case John Whitfield, scheduled to arrive within days with tribal annuities more than sufficient to settle the matter to everyone’s satisfaction.

Chief Conquering Bear attempted to negotiate recompense, offering a horse or cow from the tribe’s herd. The owner refused, demanding $25. That same treaty of 1851 specified that such matters would be handled by the local Indian agent, in this case John Whitfield, scheduled to arrive within days with tribal annuities more than sufficient to settle the matter to everyone’s satisfaction.

The tale of those other two columns is worth a “Today in History” essay of their own if not an entire book, but this is a story about Little Big Horn. Suffice it to say that Major Marcus Reno‘s experience of this day was as grizzly and as shocking, as that moment when the brains and face of his Arikara scout Bloody Knife spattered across his own. Reno’s detachment had entered a buzz saw and would have been annihilated altogether, had it not met up with that of captain Frederick Benteen.

The tale of those other two columns is worth a “Today in History” essay of their own if not an entire book, but this is a story about Little Big Horn. Suffice it to say that Major Marcus Reno‘s experience of this day was as grizzly and as shocking, as that moment when the brains and face of his Arikara scout Bloody Knife spattered across his own. Reno’s detachment had entered a buzz saw and would have been annihilated altogether, had it not met up with that of captain Frederick Benteen.

Most such outbreaks coincided with periods of extreme hardship such as crop failure, famine and floods, and involved between dozens and tens of thousands of individuals.

Most such outbreaks coincided with periods of extreme hardship such as crop failure, famine and floods, and involved between dozens and tens of thousands of individuals. Even today there is little consensus about what caused the phenomenon. Some have blamed “St Anthony’s Fire”, a toxic and psychoactive fungus of the Claviceps genus, also known as ergot. Often ingested with infected rye bread, symptoms of ergot poisoning are not unlike those of LSD, and include nervous spasms, psychotic delusions, spontaneous abortion, convulsions and gangrene resulting from severe vasoconstriction.

Even today there is little consensus about what caused the phenomenon. Some have blamed “St Anthony’s Fire”, a toxic and psychoactive fungus of the Claviceps genus, also known as ergot. Often ingested with infected rye bread, symptoms of ergot poisoning are not unlike those of LSD, and include nervous spasms, psychotic delusions, spontaneous abortion, convulsions and gangrene resulting from severe vasoconstriction.

There is an oft-repeated but mistaken notion that the circus goes back to Roman antiquity. The panem et circenses, (bread and circuses)” of Juvenal, ca AD100, refers more to the ancient precursor of the racetrack, than to anything resembling a modern circus. The only common denominator is the word itself, the Latin root ‘circus’, translating into English, as “circle”.

There is an oft-repeated but mistaken notion that the circus goes back to Roman antiquity. The panem et circenses, (bread and circuses)” of Juvenal, ca AD100, refers more to the ancient precursor of the racetrack, than to anything resembling a modern circus. The only common denominator is the word itself, the Latin root ‘circus’, translating into English, as “circle”. These afternoon shows gained overwhelming popularity by 1770, and Astley hired acrobats, rope-dancers, and jugglers to fill the spaces between equestrian events. The modern circus, was born.

These afternoon shows gained overwhelming popularity by 1770, and Astley hired acrobats, rope-dancers, and jugglers to fill the spaces between equestrian events. The modern circus, was born.

and fear, his demonstrations emphasizing the animal’s intelligence and tractability over ferocity.

and fear, his demonstrations emphasizing the animal’s intelligence and tractability over ferocity.

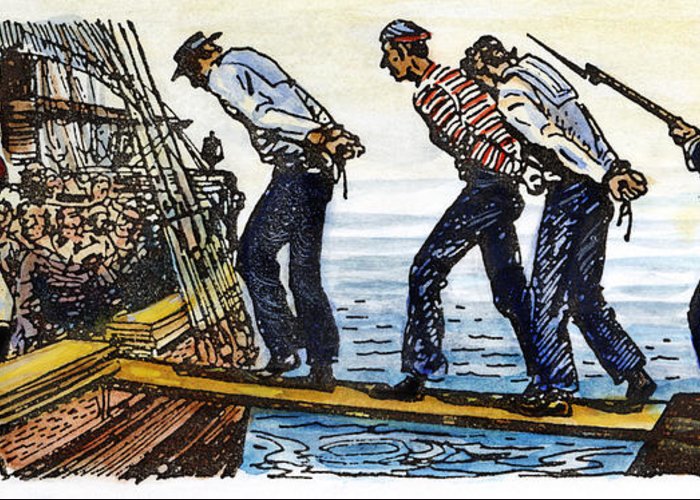

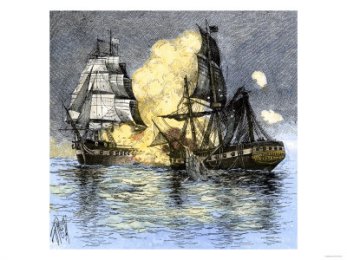

Humphreys then used a hailing trumpet and ordered the American ship to comply, to which Barron responded “I don’t hear what you say”. Humphreys fired two rounds across Chesapeake’s bow, followed immediately by four broadsides.

Humphreys then used a hailing trumpet and ordered the American ship to comply, to which Barron responded “I don’t hear what you say”. Humphreys fired two rounds across Chesapeake’s bow, followed immediately by four broadsides.

United States Naval Captain James Lawrence was eager to comply, confident in the wake of a number of American victories in single-ship actions.

United States Naval Captain James Lawrence was eager to comply, confident in the wake of a number of American victories in single-ship actions.

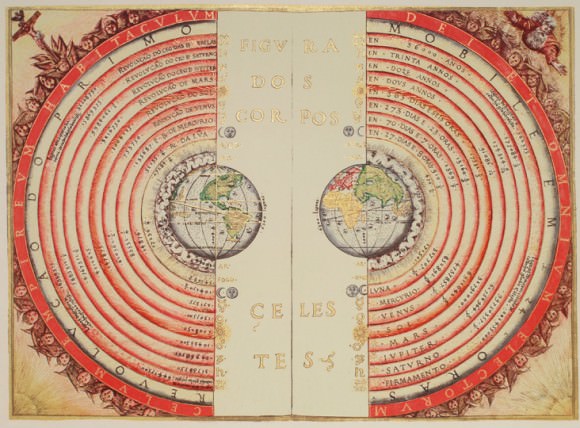

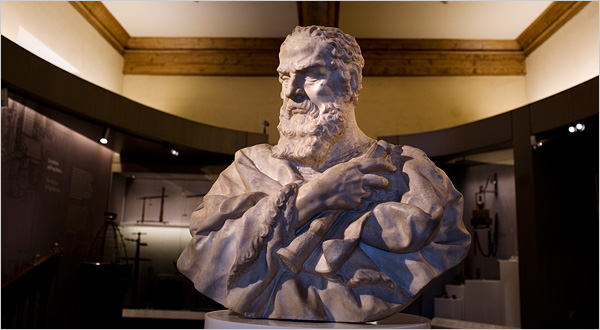

Some 100 years later, two fingers and a tooth were purchased at auction, and have since rejoined their fellow digit at the Museo Galileo. To this day, these remain the only human body parts, in a museum otherwise devoted to scientific instrumentation.

Some 100 years later, two fingers and a tooth were purchased at auction, and have since rejoined their fellow digit at the Museo Galileo. To this day, these remain the only human body parts, in a museum otherwise devoted to scientific instrumentation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.