In the early months of the “Great War”, the British Royal Navy imposed a surface blockade on the German high seas fleet. Even food was treated as a “contraband of war”, a measure widely regarded as an attempt to starve the German population. With good reason. One academic study performed ten years after the war, put the death toll by starvation at 424,000 in Germany alone. The German undersea fleet responded with a blockade of the British home islands, a devastating measure carried out against an island adversary dependent on massive levels of imports.

World War 2 was a time of few restrictions on submarine warfare. Belligerents attacked military and merchant vessels alike with prodigious loss of civilian life, but WW1 didn’t start out that way.

Wary of antagonizing neutral opinion, German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg argued against a “shoot without warning”policy but, strict adherence to maritime prize rules risked U-Boats and crews alike. By early 1915, Germany declared the waters surrounding the British home Isles a war zone where even the vessels of neutral nations were at risk of being sunk.

Desperate to find an effective countermeasure to the German “Unterseeboot”, Great Britain introduced heavily armed merchant ships with concealed weaponry in 1915, phony merchantmen designed to lure submarines into making surface attacks. Britain called these secret countermeasures “Q-ships”, after their home base in Queenstown, in Ireland.

German sailors called them U-Boot-Fälle. “U-boat traps”.

The “unprovoked” sinking of noncombatant vessels, including the famous Lusitania in which 1,198 passengers lost their lives, became a primary justification for war. The German Empire, for her part, insisted that many of these vessels carried munitions intended to kill German boys on European battlefields.

Underwater, the submarines of WWI were slow and blind, on the surface, vulnerable to attack. In 1916, German policy vacillated between strict adherence to prize rules and unrestricted submarine warfare. It was a Hobbesian choice. The first put their own people and vessels at extreme risk, the second threatened to bring neutrals like the United States and Brazil, into the war.

In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson won re-election with the slogan “He kept us out of war”: a conflict begun in Europe, two years earlier.

In a January 31, 1917 memorandum from German Ambassador Count Johann von Bernstorff to American Secretary of State Robert Lansing, the Ambassador stated that “sea traffic will be stopped with every available weapon and without further notice”, effective the following day. The German government was about to resume unrestricted submarine warfare.

Anticipating this resumption and expecting the decision to draw the United States into the war, German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann delivered a message to the German ambassador in Mexico, Heinrich von Eckardt. The telegram instructed Ambassador Eckardt that, if the United States seemed likely to enter the war, he was to approach the Mexican Government with a proposal for military alliance, promising “lost territory” in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona in exchange for a Mexican declaration of war against the United States.

“We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona…”. Signed, ZIMMERMANN

The “Zimmermann Telegram” was intercepted and decoded by British intelligence and revealed to the American government on February 24. The contents of the message outraged American public opinion and helped generate support for the United States’ declaration of war.

In the end, the German response to anticipated US action, brought about the very action it was trying to avoid.

President Woodrow Wilson delivered his war message to a joint session of Congress on April 2, stating that a declaration of war on Imperial Germany would make the world “Safe for Democracy”. Congress voted to support American entry into the war on April 6, 1917. The “Great War”, the “War to end all Wars”, had become a World War.

At the time, a secondary explosion within the hull of RMS Lusitania caused many to believe the liner had been struck by a second torpedo. In 1968, American businessman Gregg Bemis purchased the wreck of the Lusitania for $2,400, from the Liverpool & London War Risks Insurance Association. In 2007 the Irish government granted Bemis a five-year license to conduct limited excavations at the site.

Twelve miles off the Irish coast and 300-feet down, a dive was conducted on the wreck in 2008. Remote submersible operators discovered some 4 million rounds of Remington .303 ammunition in the hold, proof of the German claim that Lusitania was, in fact, a legitimate target under international rules of war. The UK Daily Mail quoted Bemis: “There were literally tons and tons of stuff stored in unrefrigerated cargo holds that were dubiously marked cheese, butter and oysters’”.

American historian, author and journalist Wade Hampton Sides accompanied the expedition. “They are bullets that were expressly manufactured to kill Germans in World War I” he said, “bullets that British officials in Whitehall, and American officials in Washington, have long denied were aboard the Lusitania.‘”

Montana Republican Jeannette Pickering Rankin, a life-long pacifist and the first woman elected to the United States Congress, would be one of only fifty votes against entering WWI. Congresswoman Rankin was elected to a second and non-consecutive term in 1940. Just in time to be the only vote against entering World War 2, in response to President Franklin Delano’s address to a joint session of Congress, December 8, 1941.

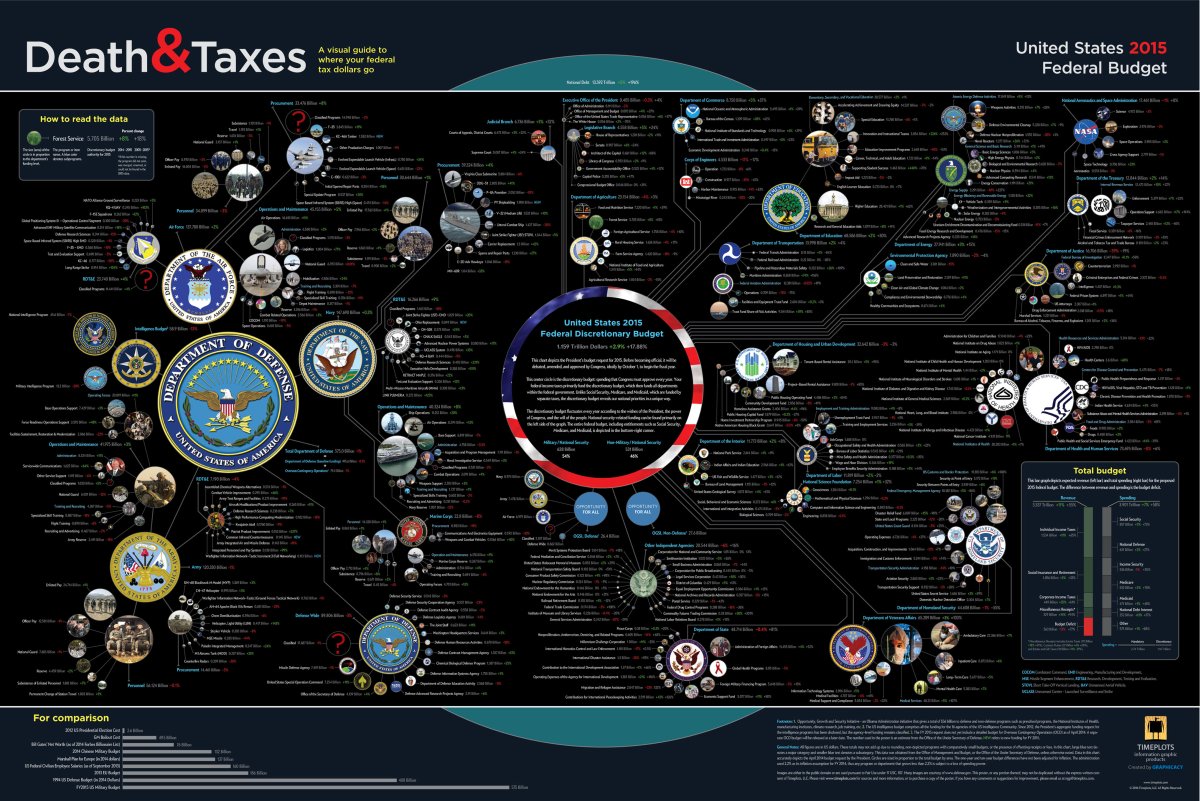

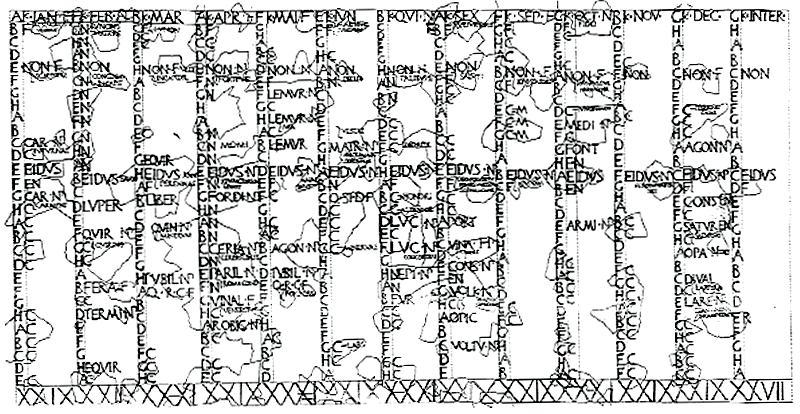

On December 31, 1695, King William III decreed a 2 shilling tax on each house in the land. Never one to miss an opportunity to “stick-it-to-the-rich”, there was an extra tax on every window over ten, a tax which would last for another 156 years.

On December 31, 1695, King William III decreed a 2 shilling tax on each house in the land. Never one to miss an opportunity to “stick-it-to-the-rich”, there was an extra tax on every window over ten, a tax which would last for another 156 years. In Holland, they used to tax the frontage of a home, the wider your house the more you paid. If you’ve ever been to Amsterdam, narrow houses rise several stories, with hooks over windows almost as wide as the building itself. These are used to haul furniture up from the outside, since the stairways are too narrow. The narrowest home in Amsterdam can be found at Singel #7, the house itself barely wider than its own front door.

In Holland, they used to tax the frontage of a home, the wider your house the more you paid. If you’ve ever been to Amsterdam, narrow houses rise several stories, with hooks over windows almost as wide as the building itself. These are used to haul furniture up from the outside, since the stairways are too narrow. The narrowest home in Amsterdam can be found at Singel #7, the house itself barely wider than its own front door. The Roman Emperor Vespasian who ruled from 69 to 79AD, levied a tax on public toilets. When Vespasian’s son, the future Emperor Titus wrinkled his nose, the old man held a coin under the boy’s nose. “Pecunia non olet”, he said. “Money does not stink”. 2,000 years later, the name remains inseparable from public urinals. In France, the er…pissoir… is called vespasiennes, in Italy vespasiani. If you need to piss in Romania you could go to the vespasiene. History fails to record the inevitable push-back on Vespasian’s toilet tax, but I’m sure that ancient Romans had to look where they walked.

The Roman Emperor Vespasian who ruled from 69 to 79AD, levied a tax on public toilets. When Vespasian’s son, the future Emperor Titus wrinkled his nose, the old man held a coin under the boy’s nose. “Pecunia non olet”, he said. “Money does not stink”. 2,000 years later, the name remains inseparable from public urinals. In France, the er…pissoir… is called vespasiennes, in Italy vespasiani. If you need to piss in Romania you could go to the vespasiene. History fails to record the inevitable push-back on Vespasian’s toilet tax, but I’m sure that ancient Romans had to look where they walked. Environmentalist types in Venice, Italy have been pushing a tax on tourism, claiming the city’s facing “an irreversible environmental catastrophe as the subsequent increase in water transport has caused the level of the lagoon bed to drop over time”. Deputy mayor Sandro Simionato said that “This tax is a new and important opportunity for the city,” explaining that it will “help finance tourism”, among other things. So, the problem borne of too much tourism is going to be fixed by a tax to help finance tourism. I think. Or maybe it’s all just another money grab.

Environmentalist types in Venice, Italy have been pushing a tax on tourism, claiming the city’s facing “an irreversible environmental catastrophe as the subsequent increase in water transport has caused the level of the lagoon bed to drop over time”. Deputy mayor Sandro Simionato said that “This tax is a new and important opportunity for the city,” explaining that it will “help finance tourism”, among other things. So, the problem borne of too much tourism is going to be fixed by a tax to help finance tourism. I think. Or maybe it’s all just another money grab. As of December 2015, state and territory tax rates on cigarettes ranged from 17¢ per pack in Missouri to $4.35 in New York, on top of federal, local, county, municipal and local Boy Scout council taxes (kidding). Philip Morris reports that taxes run 56.6% on average, per pack. Not surprisingly, tax rates make a vast difference in where and how people buy cigarettes. There is a tiny Indian reservation on Long Island, measuring a few miles square and home to a few hundred people. Tax rates are close to zero there, on a pack of butts. Until recent changes in tax law, the tiny reservation was selling 100 million cartons per year.

As of December 2015, state and territory tax rates on cigarettes ranged from 17¢ per pack in Missouri to $4.35 in New York, on top of federal, local, county, municipal and local Boy Scout council taxes (kidding). Philip Morris reports that taxes run 56.6% on average, per pack. Not surprisingly, tax rates make a vast difference in where and how people buy cigarettes. There is a tiny Indian reservation on Long Island, measuring a few miles square and home to a few hundred people. Tax rates are close to zero there, on a pack of butts. Until recent changes in tax law, the tiny reservation was selling 100 million cartons per year. Back in 2013, EU politicians were discussing a way of taxing livestock flatulence, as a means of curbing “Global Warming”. At that time there was an Australian ice breaker, making its way to Antarctica to free the Chinese ice breaker that got stuck in the ice trying to free the Russian ship full of environmentalist types. They were all there to view the effects of “Global Warming”, until they got stuck in the ice.

Back in 2013, EU politicians were discussing a way of taxing livestock flatulence, as a means of curbing “Global Warming”. At that time there was an Australian ice breaker, making its way to Antarctica to free the Chinese ice breaker that got stuck in the ice trying to free the Russian ship full of environmentalist types. They were all there to view the effects of “Global Warming”, until they got stuck in the ice.

16th century Church doctrine taught that the Saints built a surplus of good works over a lifetime, sort of a moral bank account. Like “carbon credits” today, positive acts of faith and charity could expiate sin. Monetary contributions to the church could, so it was believed, “buy” the benefits of the saint’s good works, for the sinner.

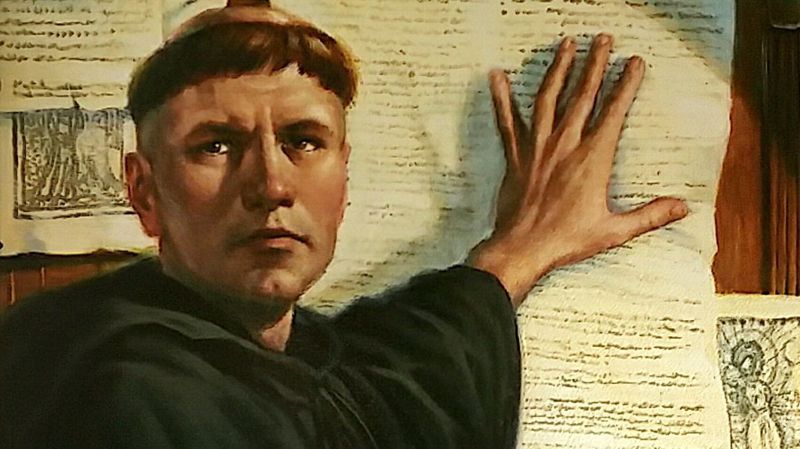

16th century Church doctrine taught that the Saints built a surplus of good works over a lifetime, sort of a moral bank account. Like “carbon credits” today, positive acts of faith and charity could expiate sin. Monetary contributions to the church could, so it was believed, “buy” the benefits of the saint’s good works, for the sinner. A popular story has Martin Luther nailing the document to the door of the Wittenberg Palace Church, but it may never have happened that way. Luther had no intention of confronting the Church at this time. This was an academic work, 95 topics offered for scholarly debate.

A popular story has Martin Luther nailing the document to the door of the Wittenberg Palace Church, but it may never have happened that way. Luther had no intention of confronting the Church at this time. This was an academic work, 95 topics offered for scholarly debate. Luther stood on dangerous ground. Jan Hus had been burned at the stake for such heresy, back in 1415. On this day in 1420, Pope Martinus I called for a crusade against the followers of the Czech priest, the “Hussieten”.

Luther stood on dangerous ground. Jan Hus had been burned at the stake for such heresy, back in 1415. On this day in 1420, Pope Martinus I called for a crusade against the followers of the Czech priest, the “Hussieten”. The papal bull had the effect of hardening Luther’s positions. He publicly burned it, on December 10. Twenty-four days later, Luther was excommunicated. A general assembly of the secular authorities of the Holy Roman Empire summoned Luther to appear before them in April, in the upper-Rhine city of Worms. The “Edict of Worms” of May 25, 1521, declared Luther an outlaw, stating “We want him to be apprehended and punished as a notorious heretic”. Anyone killing Luther was permitted to do so without legal consequence.

The papal bull had the effect of hardening Luther’s positions. He publicly burned it, on December 10. Twenty-four days later, Luther was excommunicated. A general assembly of the secular authorities of the Holy Roman Empire summoned Luther to appear before them in April, in the upper-Rhine city of Worms. The “Edict of Worms” of May 25, 1521, declared Luther an outlaw, stating “We want him to be apprehended and punished as a notorious heretic”. Anyone killing Luther was permitted to do so without legal consequence.

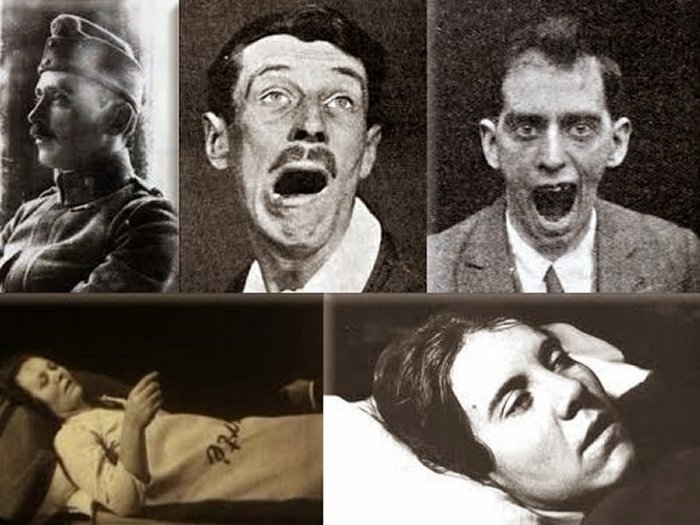

Ordinary flu strains prey most heavily on children, elderly, and those with compromised immune systems. Not this one. This flu would kick off a positive feedback loop between small proteins called cytokines, and white blood cells. This “cytokine storm” resulted in a death rate for 15 to 34-year-olds twenty times higher in 1918, than in previous years.

Ordinary flu strains prey most heavily on children, elderly, and those with compromised immune systems. Not this one. This flu would kick off a positive feedback loop between small proteins called cytokines, and white blood cells. This “cytokine storm” resulted in a death rate for 15 to 34-year-olds twenty times higher in 1918, than in previous years.

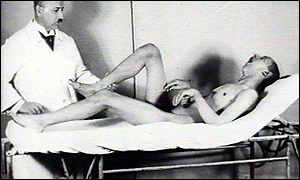

One-third of sufferers died in the acute phase, a higher mortality rate than the Spanish flu of 1918-’19. Many of those who survived never returned to pre-disease states of “aliveness” and lived out the rest of their lives institutionalized, literal prisoners of their own bodies. Living paperweights.

One-third of sufferers died in the acute phase, a higher mortality rate than the Spanish flu of 1918-’19. Many of those who survived never returned to pre-disease states of “aliveness” and lived out the rest of their lives institutionalized, literal prisoners of their own bodies. Living paperweights. Professor John Sydney Oxford is an English virologist, a leading expert on influenza, the 1918 Spanish Influenza, and HIV/AIDS. Few have done more in the modern era, to understand Encephalitis Lethargica: “I certainly do think that whatever caused it could strike again. And until we know what caused it we won’t be able to prevent it happening again.”

Professor John Sydney Oxford is an English virologist, a leading expert on influenza, the 1918 Spanish Influenza, and HIV/AIDS. Few have done more in the modern era, to understand Encephalitis Lethargica: “I certainly do think that whatever caused it could strike again. And until we know what caused it we won’t be able to prevent it happening again.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.