The first recorded drunk driving arrest came about in 1897 when London taxi driver George Smith, crashed into a building. Smith entered a plea of guilty after his arrest and was sentenced to a fine of 25 shillings, equivalent to $33.49 USD, in 2021.

In the US at this time transportation more often, involved a horse. There were 4,192 vehicles on US roads in 1900 mostly steam and electric with a mere 936 running, on internal combustion. The Automobile Club of America estimated 200,000 motorized cars in the United States in 1909. By 1916 the number skyrocketed, to 2.25 million.

As roads became more numerous and cars got faster the drunk driver’s primary concern was no longer, falling off his horse. Now pedestrians and other motorists were increasingly at risk. New York was the first state to enact drunk driving laws, in 1910.

“Prohibition” went into effect at midnight, January 16, 1920. It was now illegal to import, export, transport or sell intoxicating liquor, wine or beer in the United States.

It was a disaster. Portable stills went on sale within a week and organized smuggling was quick to follow. California grape growers increased acreage by over 700% over the first five years, selling dry blocks of grapes as “bricks of Rhine” or “blocks of Port”. The mayor of New York City personally sent instructions to constituents, on how to make wine.

Frustrated by the lack of compliance the federal government ordered the deliberate poisoning of industrial alcohols in 1926 to prevent bootleggers from “renaturing” the stuff, as drinkable alcohol. By some estimates the federal government’s poisoning program killed as many as 10,000 of its own people.

For thirteen years federal prohibition did little more than empower the mob, and destroy the nation’s 5th largest industry. It’s hard to compare alcohol consumption rates before and during prohibition but, if death by cirrhosis of the liver is any indication, alcohol consumption never went down more than 10 to 20 percent. Revelers continued to get behind the wheel, and drive.

In 1927, Dr. Emil Bogen’s landmark study established a scientific method of determining inebriation by testing the blood, urine or breath of a subject. An individual would breathe into an apparatus not unlike a football bladder where chemicals would change to various colors, depending on exposure to alcohol. Colors were then compared with a collection of vials to determination the amount of alcohol in the system. The system worked but it wasn’t very practical, for a traffic stop.

One W.D. McNally published the picture below in the November 1927 issue of Science and Invention with the promise that a method was coming soon, to reliably determine blood alcohol levels.

Prohibition was repealed in late 1933. In the first six months of 1934 Chicago reported a four-fold increase in drunk driving fatalities over the same period of the last full year, of Prohibition. Los Angeles reported similar numbers.

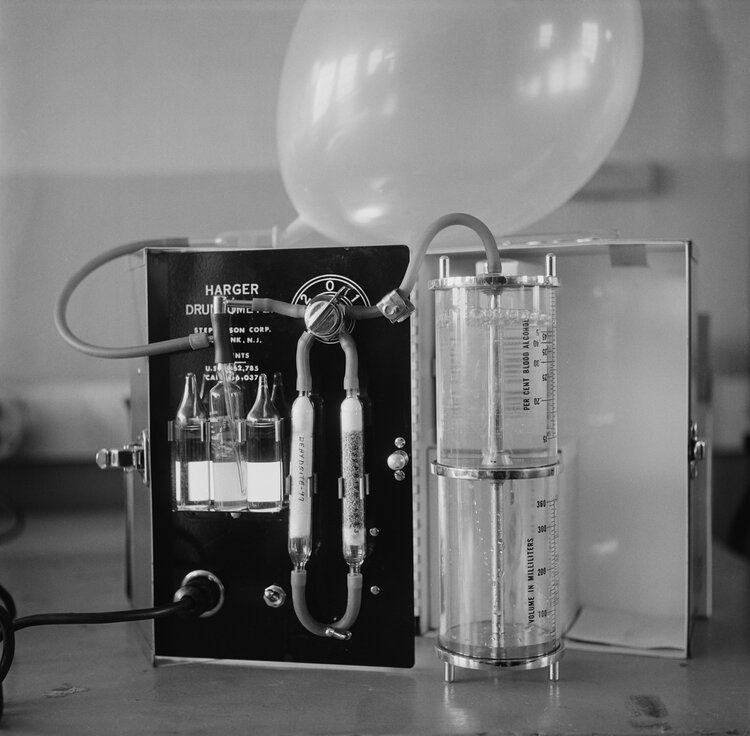

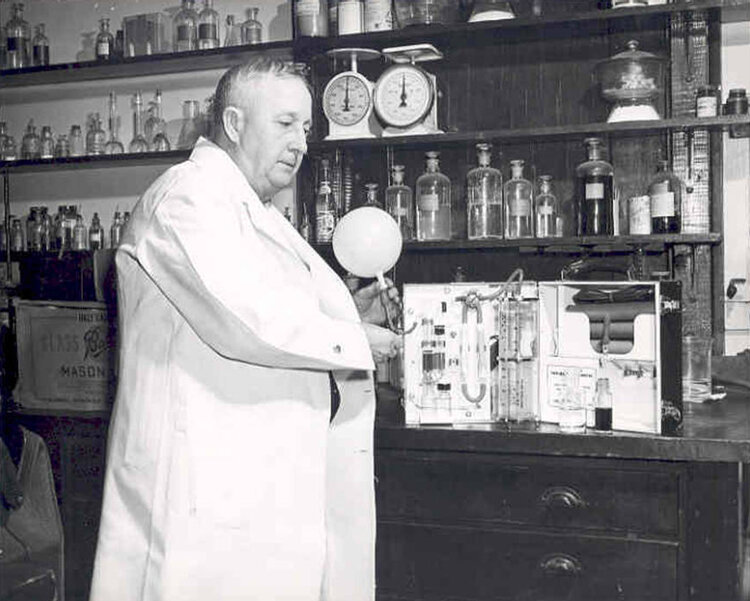

A conceptual breakthrough happened in 1931 when Indiana University biochemist Dr. Rolla N. Harger announced his own method for measuring blood alcohol content, by means of a breath test. By 1938 Harger had a working model of a new machine, small enough for practical use in the field. Indiana State Police first put the device to use on December 31.

By 1940 police departments across the nation were using Harger’s device like the one pictured here, at the New Jersey State police.

When asked what they called their device Harger and his team called the thing, a “Drunkometer”. Whether they were serious or the name was a joke is a matter for conjecture, but the modern breathalyzer, was here to stay.

Eighty three years to the day it is New Year’s Eve, 2021. Tonight, revelers the world over will celebrate the New Year. I wish you and yours a safe, healthy and prosperous new year and if you need to, you can always call a cab. Just make sure the guy’s name isn’t, George Smith.

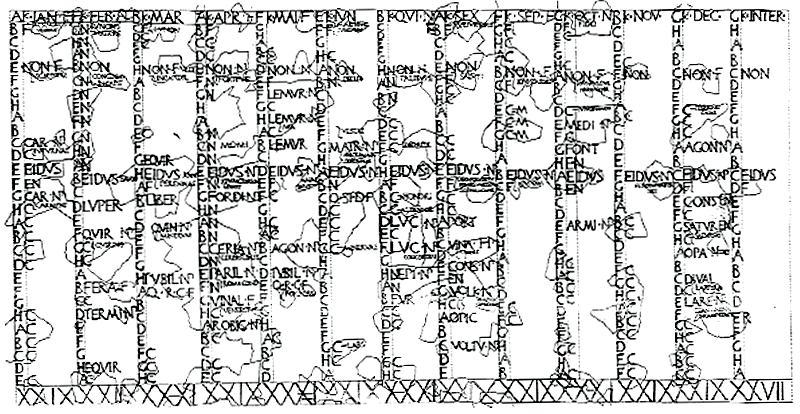

When Caesar went to Egypt in 48BC, he was impressed with the way they handled their calendar. He hired the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes to help straighten things out. The astronomer calculated that a proper year was 365¼ days, which more accurately tracked the solar, and not the lunar year. “Do like the Egyptians”, he might have said, the new “Julian” calendar going into effect in 46BC. Caesar decreed that 67 days be added that year, moving the New Year’s start from March to January 1. The first new year of the new calendar was January 1, 45BC.

When Caesar went to Egypt in 48BC, he was impressed with the way they handled their calendar. He hired the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes to help straighten things out. The astronomer calculated that a proper year was 365¼ days, which more accurately tracked the solar, and not the lunar year. “Do like the Egyptians”, he might have said, the new “Julian” calendar going into effect in 46BC. Caesar decreed that 67 days be added that year, moving the New Year’s start from March to January 1. The first new year of the new calendar was January 1, 45BC.

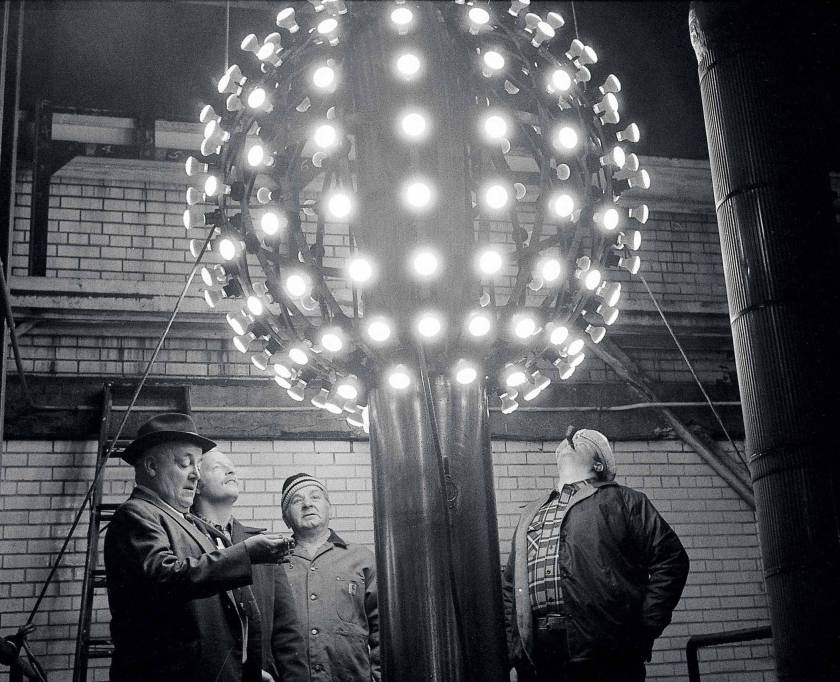

The Artkraft Strauss sign company designed a 5′ wide, 700lb ball covered with incandescent bulbs. The ball was hoist up the flagpole by five men on December 31, 1907. Once it hit the roof of the building, the ball completed an electric circuit, lighting up a sign and touching off a fireworks display.

The Artkraft Strauss sign company designed a 5′ wide, 700lb ball covered with incandescent bulbs. The ball was hoist up the flagpole by five men on December 31, 1907. Once it hit the roof of the building, the ball completed an electric circuit, lighting up a sign and touching off a fireworks display. continues. The ball used the last few years is 12′ wide, weighing 11,875lbs; a great sphere of 2,688 Waterford Crystal triangles, illuminated by 32,256 Philips Luxeon Rebel LED bulbs and producing more than 16 million colors. It used to be that the ball only came out for New Year. The last few years, you can see the thing, any time you like.

continues. The ball used the last few years is 12′ wide, weighing 11,875lbs; a great sphere of 2,688 Waterford Crystal triangles, illuminated by 32,256 Philips Luxeon Rebel LED bulbs and producing more than 16 million colors. It used to be that the ball only came out for New Year. The last few years, you can see the thing, any time you like.

You must be logged in to post a comment.