On December 7, 1941, forces of the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the United States’ Pacific naval Anchorage, at Pearl Harbor. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt addressed a joint session of Congress the following day, requesting a declaration that, since the attack, a state of war had existied between the United States, and Japan. Three days later, Nazi Germany declared war on the United States, reciprocated by an American declaration against Nazi Germany, and their Italian allies. A two-years long conflict in Europe, had become a World War.

In the months that followed, the United States ramped up its war capacity, significantly. Realizing this but having little information, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) determined to visit Pearl Harbor once again, to have a look around.

In the months that followed, the United States ramped up its war capacity, significantly. Realizing this but having little information, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) determined to visit Pearl Harbor once again, to have a look around.

For the IJN, this was an opportunity to test the new Kawanishi H8K1 “Emily” flying boat, an amphibious bomber designed to carry out long distance bombing raids. So it was that a second, albeit smaller attack was launched against Pearl Harbor.

The IJN plan was complex. This, the first Kawanishi H8K1 operation in Japanese military service, involved a small formation of flying boats to be sent to Wotje Atoll in the Marshall Islands, from there to stage the long-range attack. The five flying boats would be loaded with four 550lb bombs apiece and flown to French Frigate Shoals northwest of Oahu, there to rendezvous with three Japanese submarines, waiting to refuel them. Ten miles south of Oahu, the 356’ diesel-powered submarine I-23 was to hold watch over the operation, reporting weather and acting as “lifeguard” in case any aircraft had to ditch in the ocean.

After refueling, the bomber – reconnaissance mission would approach Pearl Harbor and attack the “10-10 dock”, so-called because it was 1,010 feet long and a key naval asset for the US Pacific Fleet.

If successful, this would be an endurance mission, one of the longest bombing raids ever attempted, and carried out entirely without fighter escort. The mission was designated “Operation K”, and scheduled for March 4, 1942.

As it turned out, the raid was a “comedy of errors”, on both sides.

Things began to go wrong, almost from the beginning. I-23 vanished. To this day nobody knows where the submarine went. American forces reported several engagements with possible subs during this time frame. Maybe one of those depth charges did its job. It is equally possible that, unknown to the Imperial Japanese Navy, I-23 was involved in an accident, lost at sea with all hands.

As it was, only two of the new flying boats were ready for the operation, the lead plane (Y-71) flown by Lieutenant Hisao Hashizume, and his “wingman” Ensign Shosuke Sasao flying the second aircraft, Y-72.

The staging and refueling parts of the operation were carried out but, absent weather intelligence from the missing I-23, the two-aircraft bombing formation was ignorant of weather conditions over the target. As it was, a thick cloud cover woud leave the Japanese pilots all but blind.

On the American side, Captain Joseph J. Rochefort, USN, worked in the Combat Intelligence Unit, tasked with intercepting enemy communications and breaking Japanese codes. US code breakers had intercepted and decoded Japanese radio communications prior to the attack of four months earlier, but urgent warnings were ignored by naval authorities at Pearl Harbor.

Once again, Rochefort’s team did its job and urgent warnings were sent to Commander in Chief Pacific (CINCPAC) and to Com-14. Incredibly, these warnings too, fell on deaf ears. Rochefort was incredulous. Years later, he would describe his reaction, at the time “I just threw up my hands and said it might be a good idea to remind everybody concerned that this nation was at war.”

American radar stations on Kauai picked up and tracked the incoming aircraft, but that same cloud cover prevented defenders from spotting them. Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighters were scrambled to search for the attackers, while Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats were sent to look for non-existent Japanese aircraft carriers, assumed to have launched the two bombers.

Meanwhile, the two Japanese pilots became confused, and separated. Hashizume dropped his bombs on the side of Mt. Tantalus, about 1,000 ft. from nearby Roosevelt High School. Hashizume’s bombs left craters 6-10 ft deep and 20-30 ft across on the side of the extinct volcano. Sasao is presumed to have dropped his bombs, over the ocean.

A Los Angeles radio station reported “considerable damage to Pearl Harbor”, with 30 dead sailors and civilians, and 70 wounded. Japanese military authorities took the broadcast to heart, and considered the operation to have been a great success. Talk about ‘fake news’. As it was, the damage was limited to those craters on Mt. Tantalus, and shattered windows at Roosevelt High.

The United States Army and the US Navy blamed each other for the explosions, each accusing the other of jettisoning munitions over the volcano.

The IJN planned another such armed reconnaissance mission for the 6th or 7th of March, but rescheduled for the 10th because of damage to Hashizume’s aircraft, and the exhaustion of air crew. The second raid was carried out on March 10, but Hashizume was shot down and killed near Midway atoll, by Brewster F2A “Buffalo” fighters.

A follow-up to Operation K was scheduled for May 30, but by that time, US military intelligence had gotten wise to the IJN meet-up point. Japanese submarines arriving at French Frigate Shoals found the place mined, and swarming with American warships.

In the end, the Imperial Japanese Navy was unable to observe US Navy activity, or to keep track of American aircraft carriers. Days later, this blindness would have a catastrophic effect on the Japanese war effort, at a place called Midway.

A second crew tested the submarine on October 15, this one including Horace Hunley himself. The submarine conducted a mock attack but failed to surface afterward, this time drowning all 8 crew members.

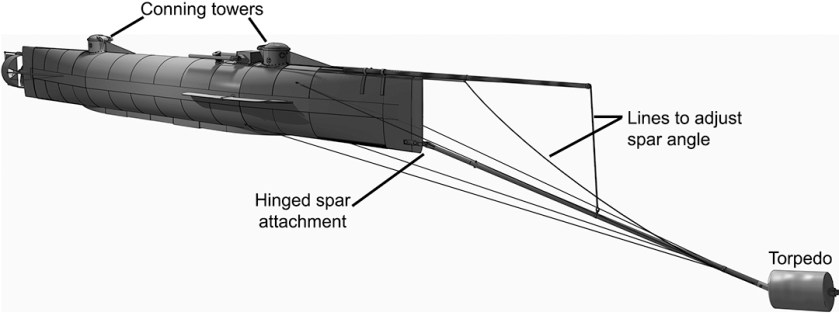

A second crew tested the submarine on October 15, this one including Horace Hunley himself. The submarine conducted a mock attack but failed to surface afterward, this time drowning all 8 crew members. Tide and current conditions in Charleston proved very different from those in Mobile. On several test runs, the torpedo floated out ahead of the sub. That wouldn’t do, so a spar was fashioned and mounted to the bow. At the end of the spar was a 137lb waterproof cask of powder, attached to a harpoon-like device with which Hunley would ram its target.

Tide and current conditions in Charleston proved very different from those in Mobile. On several test runs, the torpedo floated out ahead of the sub. That wouldn’t do, so a spar was fashioned and mounted to the bow. At the end of the spar was a 137lb waterproof cask of powder, attached to a harpoon-like device with which Hunley would ram its target.

On the coin, clearly showing signs of having been struck by a bullet, are inscribed these words:

On the coin, clearly showing signs of having been struck by a bullet, are inscribed these words:

The “Battle of the Atlantic” lasted 5 years, 8 months and 5 days, ranging from the Irish Sea to the Gulf of Mexico, from the Caribbean to the Arctic Ocean. Winston Churchill would describe this as “the dominating factor all through the war. Never for a moment could we forget that everything happening elsewhere, on land, at sea or in the air depended ultimately on its outcome”.

The “Battle of the Atlantic” lasted 5 years, 8 months and 5 days, ranging from the Irish Sea to the Gulf of Mexico, from the Caribbean to the Arctic Ocean. Winston Churchill would describe this as “the dominating factor all through the war. Never for a moment could we forget that everything happening elsewhere, on land, at sea or in the air depended ultimately on its outcome”. New weapons and tactics would shift the balance first in favor of one side, and then to the other. In the end over 3,500 merchant ships and 175 warships would be sunk to the bottom of the ocean, compared with the loss of 783 U-boats.

New weapons and tactics would shift the balance first in favor of one side, and then to the other. In the end over 3,500 merchant ships and 175 warships would be sunk to the bottom of the ocean, compared with the loss of 783 U-boats.

and crews to breathe while running submerged. Venturer was on batteries when the first sounds were detected, giving the British sub the stealth advantage but sharply limiting the time frame in which it could act.

and crews to breathe while running submerged. Venturer was on batteries when the first sounds were detected, giving the British sub the stealth advantage but sharply limiting the time frame in which it could act. With four incoming at as many depths, the German sub didn’t have time to react. Wolfram was only just retrieving his snorkel and converting to electric, when the #4 torpedo struck. U-864 imploded and sank, instantly killing all 73 aboard.

With four incoming at as many depths, the German sub didn’t have time to react. Wolfram was only just retrieving his snorkel and converting to electric, when the #4 torpedo struck. U-864 imploded and sank, instantly killing all 73 aboard.

Those who could escape scrambled onto the deck, injured, disoriented, many still in their underwear as they emerged into the cold and darkness.

Those who could escape scrambled onto the deck, injured, disoriented, many still in their underwear as they emerged into the cold and darkness. Dorchester was listing hard to starboard and taking on water fast, with only 20 minutes to live. Port side lifeboats were inoperable due to the ship’s angle. Men jumped across the void into those on the starboard side, overcrowding them to the point of capsize. Only two of fourteen lifeboats launched successfully.

Dorchester was listing hard to starboard and taking on water fast, with only 20 minutes to live. Port side lifeboats were inoperable due to the ship’s angle. Men jumped across the void into those on the starboard side, overcrowding them to the point of capsize. Only two of fourteen lifeboats launched successfully. Rushing back to the scene, coast guard cutters found themselves in a sea of bobbing red lights, the water-activated emergency strobe lights of individual life jackets. Most marked the location of corpses. Of the 904 on board, the Coast Guard plucked 230 from the water, alive.

Rushing back to the scene, coast guard cutters found themselves in a sea of bobbing red lights, the water-activated emergency strobe lights of individual life jackets. Most marked the location of corpses. Of the 904 on board, the Coast Guard plucked 230 from the water, alive. John 15:13 says “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends”. Rabbi Goode did not call out for a Jew when he gave away his only hope for survival, Father Washington did not ask for a Catholic. Neither minister Fox nor Poling asked for a Protestant. Each gave his life jacket to the nearest man.

John 15:13 says “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends”. Rabbi Goode did not call out for a Jew when he gave away his only hope for survival, Father Washington did not ask for a Catholic. Neither minister Fox nor Poling asked for a Protestant. Each gave his life jacket to the nearest man.

The act served multiple purposes, among them the modernization of what was then a largely WWI vintage merchant marine fleet, serving as the basis for a naval auxiliary that could be activated in time of war or national emergency.

The act served multiple purposes, among them the modernization of what was then a largely WWI vintage merchant marine fleet, serving as the basis for a naval auxiliary that could be activated in time of war or national emergency.

Where there are government subsidies, there are strings. For SS America, those strings were pulled on May 28, 1941, while the ship was at port in Saint Thomas, in the US Virgin Islands. The ship had been called into service by the United States Navy, and ordered to return to Newport News.

Where there are government subsidies, there are strings. For SS America, those strings were pulled on May 28, 1941, while the ship was at port in Saint Thomas, in the US Virgin Islands. The ship had been called into service by the United States Navy, and ordered to return to Newport News.

Columbus had taken his idea of a westward trade route to the Portuguese King, to Genoa and to Venice, before he came to Ferdinand and Isabella in 1486. At that time the Spanish monarchs had a

Columbus had taken his idea of a westward trade route to the Portuguese King, to Genoa and to Venice, before he came to Ferdinand and Isabella in 1486. At that time the Spanish monarchs had a  Columbus seems not to have been impressed, describing these mermaids as “not half as beautiful as they are painted.”

Columbus seems not to have been impressed, describing these mermaids as “not half as beautiful as they are painted.”

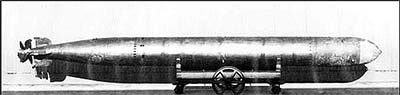

Among the Mark-XIV’s more pronounced deficiencies was a tendency to run about 10-ft. too deep, causing it to miss with depressing regularity. The magnetic exploder often caused premature firing of the warhead, and the contact exploder frequently failed altogether. There must be no worse sound to a submariner, than the metallic ‘clink’ of a dud torpedo bouncing off an enemy hull.

Among the Mark-XIV’s more pronounced deficiencies was a tendency to run about 10-ft. too deep, causing it to miss with depressing regularity. The magnetic exploder often caused premature firing of the warhead, and the contact exploder frequently failed altogether. There must be no worse sound to a submariner, than the metallic ‘clink’ of a dud torpedo bouncing off an enemy hull.

Sam Moses, writing for historynet’s “Hell and High Water,” writes, “In five war patrols between May 1944 and August 1945, the 1,500-ton Barb sank twenty-nine ships and destroyed numerous factories using shore bombardment and rockets launched from the foredeck”.

Sam Moses, writing for historynet’s “Hell and High Water,” writes, “In five war patrols between May 1944 and August 1945, the 1,500-ton Barb sank twenty-nine ships and destroyed numerous factories using shore bombardment and rockets launched from the foredeck”. Two weeks later, USS Barb spotted a 30-ship convoy, anchored in three parallel lines in Namkwan Harbor, on the China coast. Slipping past the Japanese escort guarding the harbor entrance under cover of darkness, the American submarine crept to within 3,000 yards.

Two weeks later, USS Barb spotted a 30-ship convoy, anchored in three parallel lines in Namkwan Harbor, on the China coast. Slipping past the Japanese escort guarding the harbor entrance under cover of darkness, the American submarine crept to within 3,000 yards. On completion of her 11th patrol, USS Barb underwent overhaul and alterations, including the installation of 5″ rocket launchers, setting out on her 12th and final patrol in early June.

On completion of her 11th patrol, USS Barb underwent overhaul and alterations, including the installation of 5″ rocket launchers, setting out on her 12th and final patrol in early June. Working so close to a Japanese guard tower that they could almost hear the snoring of the sentry, the eight-man team dug into the space between two ties and buried the 55-pound scuttling charge. They then dug into the space between the next two ties, and placed the battery.

Working so close to a Japanese guard tower that they could almost hear the snoring of the sentry, the eight-man team dug into the space between two ties and buried the 55-pound scuttling charge. They then dug into the space between the next two ties, and placed the battery.

Once considered mythical but for the old sailor’s stories and the damage inflicted on ships themselves, the first scientific measurement of a rogue wave occurred in the North sea in 1984, when a 36′ wave was measured off the Gorm oil platform, in a relatively placid sea.

Once considered mythical but for the old sailor’s stories and the damage inflicted on ships themselves, the first scientific measurement of a rogue wave occurred in the North sea in 1984, when a 36′ wave was measured off the Gorm oil platform, in a relatively placid sea.

In 1909, the 500-ft. cargo liner SS Waratah disappeared off Durban South Africa, with 211 passengers and crew.

In 1909, the 500-ft. cargo liner SS Waratah disappeared off Durban South Africa, with 211 passengers and crew.

The American public was outraged and there were calls for war in 1807, when HMS Leopard overtook the USS Chesapeake, kidnapping three American-born sailors and one British deserter, leaving another three dead and 18 wounded.

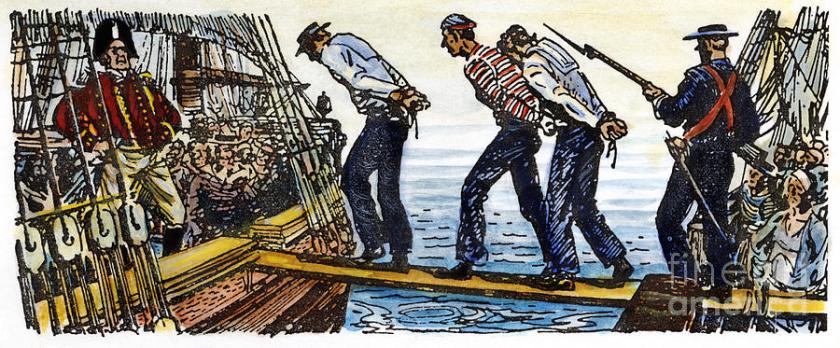

The American public was outraged and there were calls for war in 1807, when HMS Leopard overtook the USS Chesapeake, kidnapping three American-born sailors and one British deserter, leaving another three dead and 18 wounded. Outside of the British Royal Navy, the practice of kidnapping people to serve as shipboard labor was known as “crimping”. Low wages combined with the gold rushes of the 19th century left the waterfront painfully short of manpower, skilled and unskilled, alike. “Boarding Masters” had the job of putting together ship’s crews, and were paid for each recruit. There was strong incentive to produce as many able bodies, as possible. Unwilling men were “shanghaied” by means of trickery, intimidation or violence, most often rendered unconscious and delivered to waiting ships, for a fee.

Outside of the British Royal Navy, the practice of kidnapping people to serve as shipboard labor was known as “crimping”. Low wages combined with the gold rushes of the 19th century left the waterfront painfully short of manpower, skilled and unskilled, alike. “Boarding Masters” had the job of putting together ship’s crews, and were paid for each recruit. There was strong incentive to produce as many able bodies, as possible. Unwilling men were “shanghaied” by means of trickery, intimidation or violence, most often rendered unconscious and delivered to waiting ships, for a fee.

San Francisco political bosses William T. Higgins, (R) and Chris “Blind Boss” Buckley (D) were both notable crimps, and well positioned to look after their political interests. Notorious crimps such as Joseph “Frenchy” Franklin and George Lewis were elected to the California state legislature. There was no better spot, from which to ensure that no legislation would interfere with such a lucrative trade.

San Francisco political bosses William T. Higgins, (R) and Chris “Blind Boss” Buckley (D) were both notable crimps, and well positioned to look after their political interests. Notorious crimps such as Joseph “Frenchy” Franklin and George Lewis were elected to the California state legislature. There was no better spot, from which to ensure that no legislation would interfere with such a lucrative trade. Imagine the hangover the next morning, to wake up and find you’re now at sea, bound for somewhere in the far east. Regulars knew about the trap door and avoided it at all costs, knowing that anyone going over there, was “fair game”.

Imagine the hangover the next morning, to wake up and find you’re now at sea, bound for somewhere in the far east. Regulars knew about the trap door and avoided it at all costs, knowing that anyone going over there, was “fair game”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.