The Mayflower set sail from England on September 6, 1620, and fetched up on the outer reaches of Cape Cod in mid-November, near the present-day site of Provincetown Harbor.

One was born over those 66 days at sea, another died. They were 101 in all, including forty members of the English Separatist Church, a radical Puritan faction who felt the Church of England hadn’t gone far enough, in the Protestant Reformation.

There the group drew up the first written framework of government established in the United States, 41 of them signing the Mayflower Compact on board the ship on November 11, 1620.

With sandy soil and no place to shelter from North Atlantic storms, a month in that place was enough to convince them of its unsuitability. Search parties were sent out and, on December 21, the “Pilgrims“crossed Cape Cod Bay and arrived at what we now know, as Plymouth Harbor.

Fully half of them died that first winter but the rest hung on, with assistance from the Grand Sachem Massasoit (inter-tribal chief) of the Wampanoag confederacy, in the form of the emissaries, Samoset and Squanto. The Mayflower returned to England in April 1621, with half its original crew.

Three more ships arrived in Plymouth over the next two years, including the Fortune (1621), the Anne and the Little James (1623). Those who arrived on these first four ships were known as the “Old Comers” of Plymouth colony, and were given special treatment in the affairs of “America’s Home Town”.

A short seventeen years later, members of the Plymouth Colony founded the town of Taunton twenty-four miles inland, and formally incorporated the place on September 3, 1639.

In 1656, the first successful iron works in Plymouth Colony and only the third in “New England” was established in Taunton, on the Two Mile River. The Taunton Iron Works operated for over 200 years, until 1876.

The town was once home to several silver smithing operations, including Reed & Barton, F.B. Rogers, and Poole Silver. To this day, Taunton is known as the “Silver City”.

Taunton also has the distinction of flying what may have been the first distinctly American flag, in history.

First raised above the town square on October 19, 1774, the flag’s canton featured the Union Jack, on the blood red field of the British Red Ensign. The Declaration of Independence lay two years in the future for these people. They were, after all, still British subjects.

First raised above the town square on October 19, 1774, the flag’s canton featured the Union Jack, on the blood red field of the British Red Ensign. The Declaration of Independence lay two years in the future for these people. They were, after all, still British subjects.

Between hoist and fly ends were written the words “Liberty and Union”, a solemn declaration that the colonies were going to stick together, and that their rights as British citizens, were not about to be violated.

Not so long as they had something to say about it.

On October 21, 1774, the Taunton Sons of Liberty raised the flag 112-feet high on a Liberty Pole, and tacked the following inscription on that pole:

“Be it known to the present,

And to all future generations,

That the Sons of Liberty in TAUNTON

Fired with Zeal for the Preservation of

Their Rights as Men, and as American Englishmen,

And prompted by a just Resentment of

The Wrongs and Injuries offered to the

English Colonies in general, and to

This Province in particular,

Through the unjust Claims of

A British Parliament, and the

Machiavellian Policy of their fixed Resolution

To preserve sacred and inviolate

Their Birth-Rights and Charter-Rights,

And to resist, even unto Blood,

All attempts for their Subversion or Abridgement.

Born to be free, we spurn the Knaves who dare

For us the Chains of Slavery to prepare.

Steadfast, in Freedom’s Cause, we’ll live and die,

Unawed by Statesmen; Foes to Tyranny,

But if oppression brings us to our Graves,

and marks us dead, she ne’er shall mark us Slaves”.

The Taunton flag is considered to be among the oldest distinctly American flags if not the oldest, in history. The city officially adopted it on October 19, 1974, the 200th anniversary of the day it was first raised above Taunton green. Stop and see it if you ever get by. It’s there on the Liberty Pole, directly beneath the Stars and Stripes of the Star Spangled Banner.

The Meux’s Brewery Co Ltd, established in 1764, was a London brewery owned by Sir Henry Meux. What the Times article was describing was a 22′ high monstrosity, held together by 29 iron hoops.

The Meux’s Brewery Co Ltd, established in 1764, was a London brewery owned by Sir Henry Meux. What the Times article was describing was a 22′ high monstrosity, held together by 29 iron hoops. The brewery was located in the crowded slum of St. Giles, where many homes contained several people to the room.

The brewery was located in the crowded slum of St. Giles, where many homes contained several people to the room. One brewery worker was able to save his brother from drowning in the flood, but others weren’t so lucky.

One brewery worker was able to save his brother from drowning in the flood, but others weren’t so lucky. In the days that followed, the crushing poverty of the slum led some to exhibit the corpses of their family members, charging a fee for anyone who wanted to come in and see. In one house, too many people crowded in and the floor collapsed, plunging them all into a cellar full of beer.

In the days that followed, the crushing poverty of the slum led some to exhibit the corpses of their family members, charging a fee for anyone who wanted to come in and see. In one house, too many people crowded in and the floor collapsed, plunging them all into a cellar full of beer.

The harbor at Scapa flow had been home to the British deep water fleet since 1904, a time when the place truly was, all but impregnable. By 1939, anti-aircraft weaponry was all but obsolete, old block ships were disintegrating, and anti-submarine nets were inadequate to the needs of the new war.

The harbor at Scapa flow had been home to the British deep water fleet since 1904, a time when the place truly was, all but impregnable. By 1939, anti-aircraft weaponry was all but obsolete, old block ships were disintegrating, and anti-submarine nets were inadequate to the needs of the new war. The electric torpedoes of the era were highly unreliable, and this wasn’t shaping up to be their night.

The electric torpedoes of the era were highly unreliable, and this wasn’t shaping up to be their night.

John Connell Freeborn was a pilot with the RAF, and a good one, too. Credited with 13½ enemy aircraft shot down, Freeborn flew more operational hours during the Battle of Britain, than any other pilot, ending the war with a Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar, and completing his RAF career as a Wing Commander. Yet, there is a time when every hero is as green as the grass. In the beginning, John Freeborn like everyone else, were rank amateurs.

John Connell Freeborn was a pilot with the RAF, and a good one, too. Credited with 13½ enemy aircraft shot down, Freeborn flew more operational hours during the Battle of Britain, than any other pilot, ending the war with a Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar, and completing his RAF career as a Wing Commander. Yet, there is a time when every hero is as green as the grass. In the beginning, John Freeborn like everyone else, were rank amateurs.

Richard Hough and Denis Richards wrote about the episode in

Richard Hough and Denis Richards wrote about the episode in

A story comes down to us from the Royal Residence of Queen Victoria, of the hapless attendant who told a spicy story one night, at dinner. You could have watched the icicles grow, when the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland turned and said: “We are not amused“.

A story comes down to us from the Royal Residence of Queen Victoria, of the hapless attendant who told a spicy story one night, at dinner. You could have watched the icicles grow, when the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland turned and said: “We are not amused“.

1776 started out well for the cause of American independence, when the twenty-six-year-old bookseller Henry Knox emerged from a six week slog through a New England winter, at the head of a “

1776 started out well for the cause of American independence, when the twenty-six-year-old bookseller Henry Knox emerged from a six week slog through a New England winter, at the head of a “ The Continental Congress adopted the

The Continental Congress adopted the

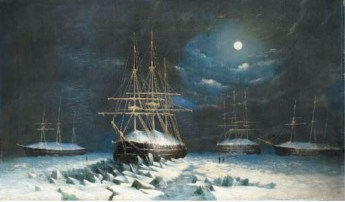

HMS Resolute was a Barque rigged merchant ship, purchased in 1850 as the Ptarmigan, and refitted for Arctic exploration. Re-named Resolute, the vessel became part of a five ship squadron leaving England in April 1852, sailing into the Canadian arctic in search of the doomed Franklin expedition.

HMS Resolute was a Barque rigged merchant ship, purchased in 1850 as the Ptarmigan, and refitted for Arctic exploration. Re-named Resolute, the vessel became part of a five ship squadron leaving England in April 1852, sailing into the Canadian arctic in search of the doomed Franklin expedition. Three of the HMS Resolute expedition’s ships themselves became trapped in floe ice in August 1853, including Resolute, herself. There was no choice but to abandon ship, striking out across the ice pack in search of their supply ships. Most of them made it, despite egregious hardship, straggling into Beechey Island in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, between May and August of the following year.

Three of the HMS Resolute expedition’s ships themselves became trapped in floe ice in August 1853, including Resolute, herself. There was no choice but to abandon ship, striking out across the ice pack in search of their supply ships. Most of them made it, despite egregious hardship, straggling into Beechey Island in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, between May and August of the following year.

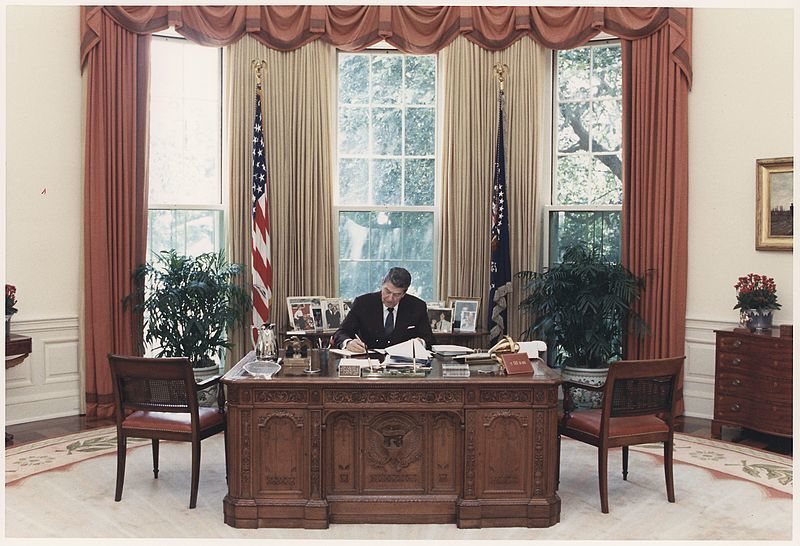

The desk, known as the Resolute Desk, has been used by nearly every American President since, whether in a private study or the oval office.

The desk, known as the Resolute Desk, has been used by nearly every American President since, whether in a private study or the oval office.

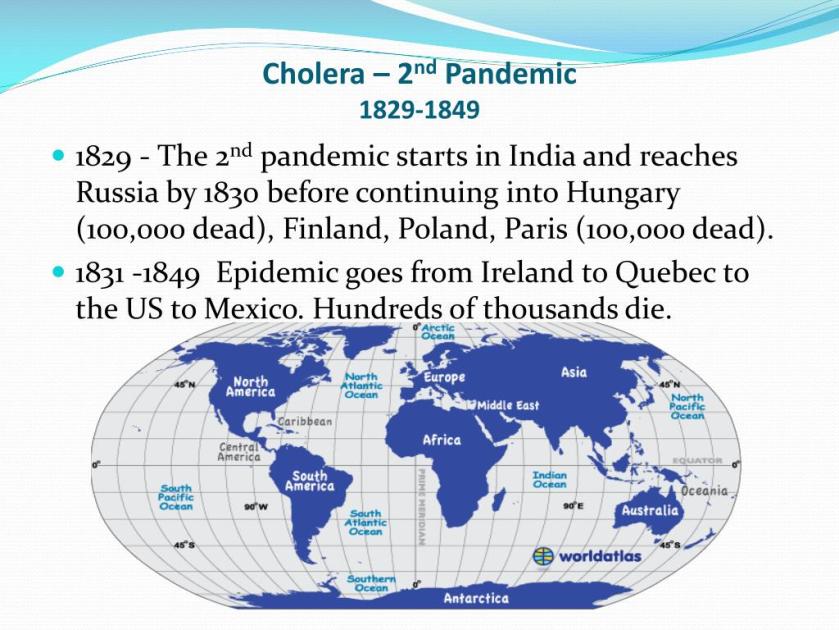

The world would see four more cholera pandemics between 1852 and 1923, with the first being by far, the deadliest. This one devastated much of Asia, North America and Africa. in 1854, the worst year of the outbreak, 23,000 died in Great Britain, alone.

The world would see four more cholera pandemics between 1852 and 1923, with the first being by far, the deadliest. This one devastated much of Asia, North America and Africa. in 1854, the worst year of the outbreak, 23,000 died in Great Britain, alone.

Several other outbreaks had occurred that year, but this one was particularly acute. Within the next three days, 127 died within a short distance of the Broad Street address. By September 10, there were five-hundred more.

Several other outbreaks had occurred that year, but this one was particularly acute. Within the next three days, 127 died within a short distance of the Broad Street address. By September 10, there were five-hundred more.

You must be logged in to post a comment.