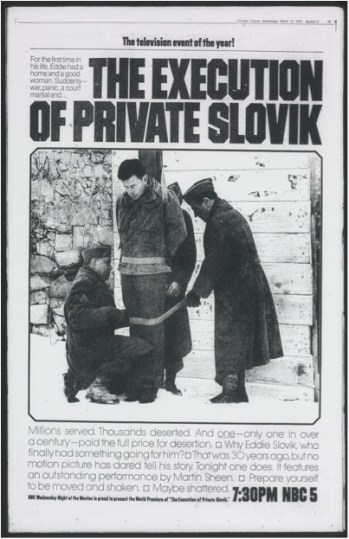

When he was little, his neighbors must have thought he was a bad kid. His first arrest came at age 12, when he and some friends were caught stealing brass from a foundry. There were other episodes between 1932 and ’37: petty theft, breaking & entering, and disturbing the peace. He was sent to prison in 1939, for stealing a car.

Edward Donald “Eddie” Slovik was paroled in 1942, his criminal record rendering him 4F. “Registrant not acceptable for military service”. He took a job at the Montella Plumbing & Heating company in Dearborn, Michigan, where he met bookkeeper Antoinette Wisniewski, the woman who would later become his wife.

There the couple may have ridden out WWII, but the war was consuming manpower at a rate unprecedented in history. Shortly after the couple’s first anniversary, Slovik was re-classified 1A, fit for service, and drafted into the Army. Arriving in France on August 20, 1944, he was part of a 12-man replacement detachment, assigned to Company G of the 109th Infantry Regiment, US 28th Infantry Division.

There the couple may have ridden out WWII, but the war was consuming manpower at a rate unprecedented in history. Shortly after the couple’s first anniversary, Slovik was re-classified 1A, fit for service, and drafted into the Army. Arriving in France on August 20, 1944, he was part of a 12-man replacement detachment, assigned to Company G of the 109th Infantry Regiment, US 28th Infantry Division.

Slovik and a buddy from basic training, Private John Tankey, became separated from their detachment during an artillery attack and spent the next six weeks with Canadian MPs. It was around this time that Private Slovik decided he “wasn’t cut out for combat”.

The rapid movement of the army during this period caused difficulty for many replacements attempting to find their units. Edward Slovik and John Tankey finally caught up with the 109th on October 7. The following day, Slovik asked his company commander Captain Ralph Grotte for reassignment to a rear unit, saying he was “too scared” to be part of a rifle company. Grotte refused, confirming that, were he to run away, such an act would constitute desertion.

And desert, he did. Eddie Slovik left his unit on October 9, despite Private Tankey’s protestations that he should stay. “My mind is made up”, he said. Slovik walked several miles until he found an enlisted cook, to whom he presented the following note.

“I, Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik, 36896415, confess to the desertion of the United States Army. At the time  of my desertion we were in Albuff [Elbeuf] in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my fox hole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.P. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE. — Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415”.

of my desertion we were in Albuff [Elbeuf] in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my fox hole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.P. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE. — Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415”.

Slovik was repeatedly ordered to tear up the note and rejoin his unit, and there would be no consequences. Each time, he refused. The stockade didn’t scare him. He’d been in prison before and it was better than the front lines. Beside that, he was already an ex-con. A dishonorable discharge was hardly going to change anything in an already dim future. Finally, instructed to write a second note on the back of the first acknowledging the legal consequences of his actions, Eddie Slovik was taken into custody.

1.7 million courts-martial were held during WWII, 1/3rd of all the criminal cases tried in the United States during the period. The death penalty was rarely imposed. When it was, it was almost always in cases of rape or murder.

2,864 US Army personnel were tried for desertion between January 1942 and June 1948. Courts-martial handed down death sentences to 49 of them, including Eddie Slovik. Division commander Major General Norman Cota approved the sentence. “Given the situation as I knew it in November, 1944,” he said, “I thought it was my duty to this country to approve that sentence. If I hadn’t approved it–if I had let Slovik accomplish his purpose–I don’t know how I could have gone up to the line and looked a good soldier in the face.”

On December 9, Slovik wrote to Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, pleading for clemency. Desertion was a systemic problem at this time. Particularly after the surprise German offensive coming out of the frozen Ardennes Forest on December 16, an action that went into history as the Battle of the Bulge. Eisenhower approved the execution order on December 23, believing it to be the only way to discourage further desertions.

On December 9, Slovik wrote to Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, pleading for clemency. Desertion was a systemic problem at this time. Particularly after the surprise German offensive coming out of the frozen Ardennes Forest on December 16, an action that went into history as the Battle of the Bulge. Eisenhower approved the execution order on December 23, believing it to be the only way to discourage further desertions.

His uniform stripped of all insignia with an army blanket draped over his shoulders, Slovik was brought to the place of execution near the Vosges Mountains of France. “They’re not shooting me for deserting the United States Army”, he said, “thousands of guys have done that. They just need to make an example out of somebody and I’m it because I’m an ex-con. I used to steal things when I was a kid, and that’s what they are shooting me for. They’re shooting me for the bread and chewing gum I stole when I was 12 years old.”

Army Chaplain Father Carl Patrick Cummings said, “Eddie, when you get up there, say a little prayer for me.” Slovik said, “Okay, Father. I’ll pray that you don’t follow me too soon”. Those were his last words. A soldier placed the black hood over his head. The execution was carried out by firing squad. It was 10:04am local time, January 31, 1945.

Edward Donald Slovik was buried in Plot E of the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery, his marker bearing a number instead of his name. Antoinette Slovik received a telegram informing her that her husband had died in the European Theater of the war and a letter, instructing her to return a $55 allotment check. She wouldn’t learn about the execution for another nine years.

In 1987, President Ronald Reagan ordered the repatriation of Slovik’s remains. He was re-interred at Detroit’s Woodmere Cemetery next to Antoinette who had gone to her final rest, eight years earlier.

In all theaters of WWII, the United States military executed 102 of its own, almost always for the unprovoked rape and/or murder of civilians. From the Civil War to this day, the execution of Private Slovik was the only time a death sentence was carried out for the crime of desertion. At least one member of the tribunal which condemned him to death, would come to see it as a miscarriage of justice.

Nick Gozik of Pittsburg passed away in 2015, at the age of 95. He was there in 1945, a fellow soldier called to witness the execution. “Justice or legal murder”, he said, “I don’t know, but I want you to know I think he was the bravest man in that courtyard that day…All I could see was a young soldier, blond-haired, walking as straight as a soldier ever walked. I thought he was the bravest soldier I ever saw.”

Nick Gozik of Pittsburg passed away in 2015, at the age of 95. He was there in 1945, a fellow soldier called to witness the execution. “Justice or legal murder”, he said, “I don’t know, but I want you to know I think he was the bravest man in that courtyard that day…All I could see was a young soldier, blond-haired, walking as straight as a soldier ever walked. I thought he was the bravest soldier I ever saw.”

In it, a follower called Yen Yüan asked the Master about perfect virtue.

In it, a follower called Yen Yüan asked the Master about perfect virtue. In medieval Japanese, mi-zaru, kika-zaru, and iwa-zaru translate as “don’t see, don’t hear, and don’t speak”, –zaru being an archaic negative verb conjugation and pronounced similarly to “saru”, the word for monkey.

In medieval Japanese, mi-zaru, kika-zaru, and iwa-zaru translate as “don’t see, don’t hear, and don’t speak”, –zaru being an archaic negative verb conjugation and pronounced similarly to “saru”, the word for monkey. The first known depiction of the “Three Mystic Apes” appears over the doors of the Tōshō-gū shrine in Nikkō, Japan, carved sometime in the 17th century.

The first known depiction of the “Three Mystic Apes” appears over the doors of the Tōshō-gū shrine in Nikkō, Japan, carved sometime in the 17th century. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was a Hindu lawyer, a member of the merchant caste from coastal Gujarat, in western India. Today he is known by the honorific “Mahatma”, from Gandhithe Sanskrit meaning “high-souled”, or “venerable”.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was a Hindu lawyer, a member of the merchant caste from coastal Gujarat, in western India. Today he is known by the honorific “Mahatma”, from Gandhithe Sanskrit meaning “high-souled”, or “venerable”.

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland the following September, London Mayor Herbert Morrison was at 10 Downing Street, meeting with Chamberlain’s aide, Sir Horace Wilson. Morrison believed that the time had come for Operation Pied Piper. Only a year to the day from the Prime Minister’s “Peace in our Time” declaration, Wilson protested. “But we’re not at war yet, and we wouldn’t want to do anything to upset delicate negotiations, would we?”

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland the following September, London Mayor Herbert Morrison was at 10 Downing Street, meeting with Chamberlain’s aide, Sir Horace Wilson. Morrison believed that the time had come for Operation Pied Piper. Only a year to the day from the Prime Minister’s “Peace in our Time” declaration, Wilson protested. “But we’re not at war yet, and we wouldn’t want to do anything to upset delicate negotiations, would we?”

This was no mindless panic. Zeppelin raids had killed 1,500 civilians in London alone during the ‘Great War’. Since then, governments had become infinitely better at killing each other’s citizens.

This was no mindless panic. Zeppelin raids had killed 1,500 civilians in London alone during the ‘Great War’. Since then, governments had become infinitely better at killing each other’s citizens. All things considered, the evacuation of all that humanity ran relatively smoothly. James Roffey, founder of the Evacuees Reunion Association, recalls ‘We marched to Waterloo Station behind our head teacher carrying a banner with our school’s name on it. We all thought it was a holiday, but the only thing we couldn’t work out was why the women and girls were crying.’

All things considered, the evacuation of all that humanity ran relatively smoothly. James Roffey, founder of the Evacuees Reunion Association, recalls ‘We marched to Waterloo Station behind our head teacher carrying a banner with our school’s name on it. We all thought it was a holiday, but the only thing we couldn’t work out was why the women and girls were crying.’ In the 2003 BBC Radio documentary “Evacuation: The True Story,” clinical psychologist Steve Davis described the worst cases, as “little more than a pedophile’s charter.”

In the 2003 BBC Radio documentary “Evacuation: The True Story,” clinical psychologist Steve Davis described the worst cases, as “little more than a pedophile’s charter.” Authorities produced posters urging parents to leave the kids where they were and a good thing, too. The Blitz against London itself began on September 7. The city experienced the most devastating attack to-date on December 29, in a blanket fire-bombing that killed almost 3,600 civilians.

Authorities produced posters urging parents to leave the kids where they were and a good thing, too. The Blitz against London itself began on September 7. The city experienced the most devastating attack to-date on December 29, in a blanket fire-bombing that killed almost 3,600 civilians. “Operation Steinbock”, the Luftwaffe’s last large-scale strategic bombing campaign of the war against southern England, was carried out three years later. On this day in 1944, 285 German bombers attacked London in what the Brits called, a “Baby Blitz”.

“Operation Steinbock”, the Luftwaffe’s last large-scale strategic bombing campaign of the war against southern England, was carried out three years later. On this day in 1944, 285 German bombers attacked London in what the Brits called, a “Baby Blitz”. Late in the war, the subsonic “Doodle Bug” or V1 “flying bomb” was replaced by the terrifying supersonic

Late in the war, the subsonic “Doodle Bug” or V1 “flying bomb” was replaced by the terrifying supersonic  In the end, many family ‘reunions’ were as emotionally bruising as the original breakup. Years had come and gone and new relationships had formed. The war had turned biological family members, into all but strangers.

In the end, many family ‘reunions’ were as emotionally bruising as the original breakup. Years had come and gone and new relationships had formed. The war had turned biological family members, into all but strangers.

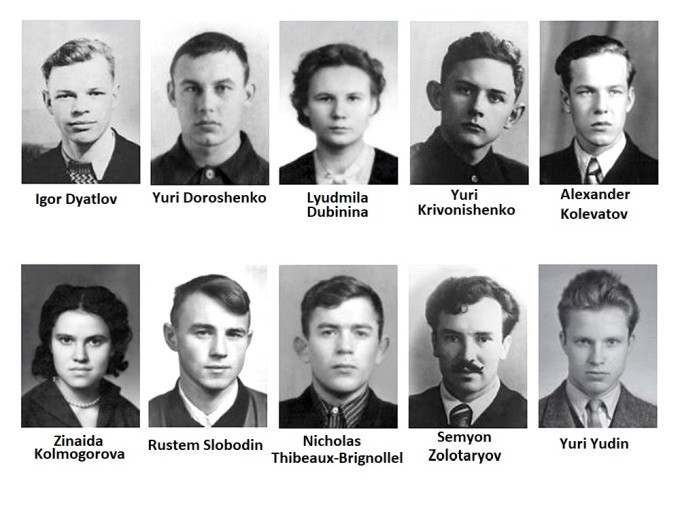

The Northern Ural is a remote and frozen place, the Ural Mountains forming the barrier between the European and Asian continents and ending in an island chain, in the Arctic Ocean. Very few live there, mostly a small ethnic minority called the Mansi people.

The Northern Ural is a remote and frozen place, the Ural Mountains forming the barrier between the European and Asian continents and ending in an island chain, in the Arctic Ocean. Very few live there, mostly a small ethnic minority called the Mansi people. The eight men and two women made it by truck as far as the tiny village of Vizhai, on the edge of the wilderness. There the group learned the ancient and not a little frightening tale of a group of Mansi hunters, mysteriously murdered on what came to be called “Dead Mountain”.

The eight men and two women made it by truck as far as the tiny village of Vizhai, on the edge of the wilderness. There the group learned the ancient and not a little frightening tale of a group of Mansi hunters, mysteriously murdered on what came to be called “Dead Mountain”. On January 28, Yuri Yudin became ill, and had to back out of the trek. The other nine agreed to carry on. None of them knew at the time. Yudin was about to become the sole survivor of a terrifying mystery.

On January 28, Yuri Yudin became ill, and had to back out of the trek. The other nine agreed to carry on. None of them knew at the time. Yudin was about to become the sole survivor of a terrifying mystery. By February 20. friends and relatives were concerned Something was wrong. Rescue expeditions were assembled, first from students and faculty of the Ural Polytechnic Institute and later by military and local police.

By February 20. friends and relatives were concerned Something was wrong. Rescue expeditions were assembled, first from students and faculty of the Ural Polytechnic Institute and later by military and local police.

Three more bodies were found leading back to the tent, frozen in postures suggesting they were trying to return. Medical investigators examined the bodies. One, that of Rustem Slobodin showed a small skull fracture, probably not enough to threaten his life. Cause of death was ruled, hypothermia.

Three more bodies were found leading back to the tent, frozen in postures suggesting they were trying to return. Medical investigators examined the bodies. One, that of Rustem Slobodin showed a small skull fracture, probably not enough to threaten his life. Cause of death was ruled, hypothermia.

Diphtheria is a highly contagious infection caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheriae, with early symptoms resembling a cold or flu. Fever, sore throat, and chills lead to bluish skin coloration, painful swallowing, and difficulty breathing.

Diphtheria is a highly contagious infection caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheriae, with early symptoms resembling a cold or flu. Fever, sore throat, and chills lead to bluish skin coloration, painful swallowing, and difficulty breathing.

Leonhard Seppala and his dog team took their turn, departing in the face of gale force winds and zero visibility, with a wind chill of −85°F.

Leonhard Seppala and his dog team took their turn, departing in the face of gale force winds and zero visibility, with a wind chill of −85°F.

Seppala was in his old age in 1960, when he recalled “I never had a better dog than Togo. His stamina, loyalty and intelligence could not be improved upon. Togo was the best dog that ever traveled the Alaska trail.”

Seppala was in his old age in 1960, when he recalled “I never had a better dog than Togo. His stamina, loyalty and intelligence could not be improved upon. Togo was the best dog that ever traveled the Alaska trail.”

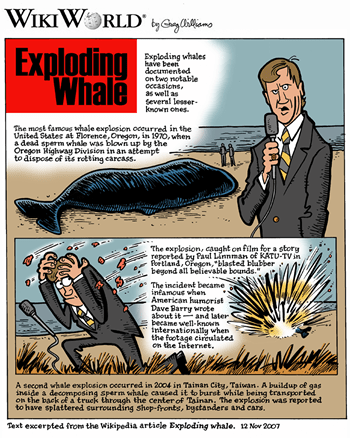

On November 12, 1970, a 45 foot, 8-ton, dead sperm whale washed up on the beaches near Florence, Oregon. State beaches came under the jurisdiction of the Department of Transportation at that time, and officials came down, to have a look.

On November 12, 1970, a 45 foot, 8-ton, dead sperm whale washed up on the beaches near Florence, Oregon. State beaches came under the jurisdiction of the Department of Transportation at that time, and officials came down, to have a look.

Umenhofer was among the crowd that day. A great slab of the stuff the size of a coffee table came down from the sky, and landed on his brand new Oldsmobile 88. He’d just bought the car from a dealer running a “Whale of a Sale” deal. You can’t make this stuff up.

Umenhofer was among the crowd that day. A great slab of the stuff the size of a coffee table came down from the sky, and landed on his brand new Oldsmobile 88. He’d just bought the car from a dealer running a “Whale of a Sale” deal. You can’t make this stuff up.

Nigh on fifty years ago, folks in the Pacific Northwest learned an important lesson on the beaches of Florence. Nine years later, 41 dead sperm whales washed ashore on the nearby coast. This time, the things were burned and buried, where they lay.

Nigh on fifty years ago, folks in the Pacific Northwest learned an important lesson on the beaches of Florence. Nine years later, 41 dead sperm whales washed ashore on the nearby coast. This time, the things were burned and buried, where they lay.

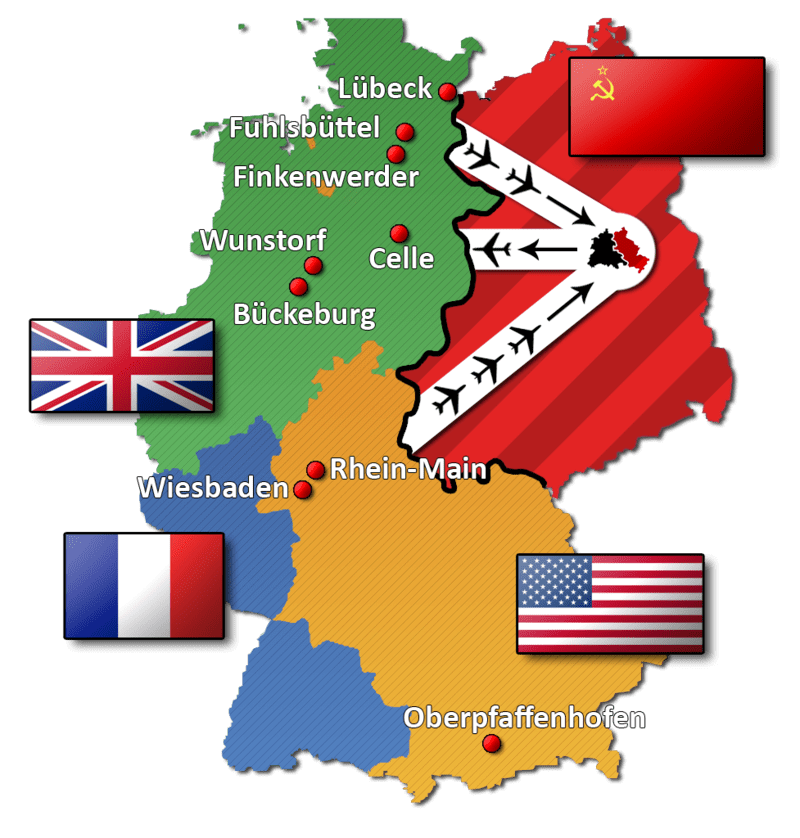

During the war, ideological fault lines were suppressed in the drive to destroy the Nazi war machine. Such differences were quick to reassert themselves in the wake of German defeat. In Soviet-occupied east Germany, factories and equipment were disassembled and transported to the Soviet Union, along with technicians, managers and skilled personnel.

During the war, ideological fault lines were suppressed in the drive to destroy the Nazi war machine. Such differences were quick to reassert themselves in the wake of German defeat. In Soviet-occupied east Germany, factories and equipment were disassembled and transported to the Soviet Union, along with technicians, managers and skilled personnel. West Berlin, a city utterly destroyed by war, was home to some 2.3 million at that time, roughly three times the city of Boston.

West Berlin, a city utterly destroyed by war, was home to some 2.3 million at that time, roughly three times the city of Boston. With that many lives at stake, allied authorities calculated a daily ration of only 1,990 calories would require 646 tons of flour and wheat, 125 tons of cereal, 64 tons of fat, 109 tons of meat and fish, 180 tons of dehydrated potatoes, 180 tons of sugar, 11 tons of coffee, 19 tons of powdered milk, 5 tons of whole milk for the children, 3 tons of fresh yeast for baking, 144 tons of dehydrated vegetables, 38 tons of salt and 10 tons of cheese.

With that many lives at stake, allied authorities calculated a daily ration of only 1,990 calories would require 646 tons of flour and wheat, 125 tons of cereal, 64 tons of fat, 109 tons of meat and fish, 180 tons of dehydrated potatoes, 180 tons of sugar, 11 tons of coffee, 19 tons of powdered milk, 5 tons of whole milk for the children, 3 tons of fresh yeast for baking, 144 tons of dehydrated vegetables, 38 tons of salt and 10 tons of cheese. What followed is known to history, as the

What followed is known to history, as the  US Army Air Force Colonel Gail “Hal” Halvorsen was one of those pilots, flying C-47s and C-54 aircraft deep inside of Soviet controlled territory. On his days off, Halvorsen liked to go sightseeing, often bringing a small movie camera.

US Army Air Force Colonel Gail “Hal” Halvorsen was one of those pilots, flying C-47s and C-54 aircraft deep inside of Soviet controlled territory. On his days off, Halvorsen liked to go sightseeing, often bringing a small movie camera. Newspapers got wind of what was going on. Halvorsen thought he’d be in trouble, but no. Lieutenant General William Henry Tunner liked the idea. A lot. “Operation Little Vittles” became official, on September 22.

Newspapers got wind of what was going on. Halvorsen thought he’d be in trouble, but no. Lieutenant General William Henry Tunner liked the idea. A lot. “Operation Little Vittles” became official, on September 22.

One day, the United States Supreme Court would rule the act an unlawful taking and compensate Lee family descendants.

One day, the United States Supreme Court would rule the act an unlawful taking and compensate Lee family descendants.

Private Christman was the first military burial, but not the first. One had come before. When Private Christman went to his rest in our nation’s most hallowed ground, his grave joined that of Mary Randolph, laid to rest some thirty-six years earlier.

Private Christman was the first military burial, but not the first. One had come before. When Private Christman went to his rest in our nation’s most hallowed ground, his grave joined that of Mary Randolph, laid to rest some thirty-six years earlier.

Mary Randolph, a direct descendant of

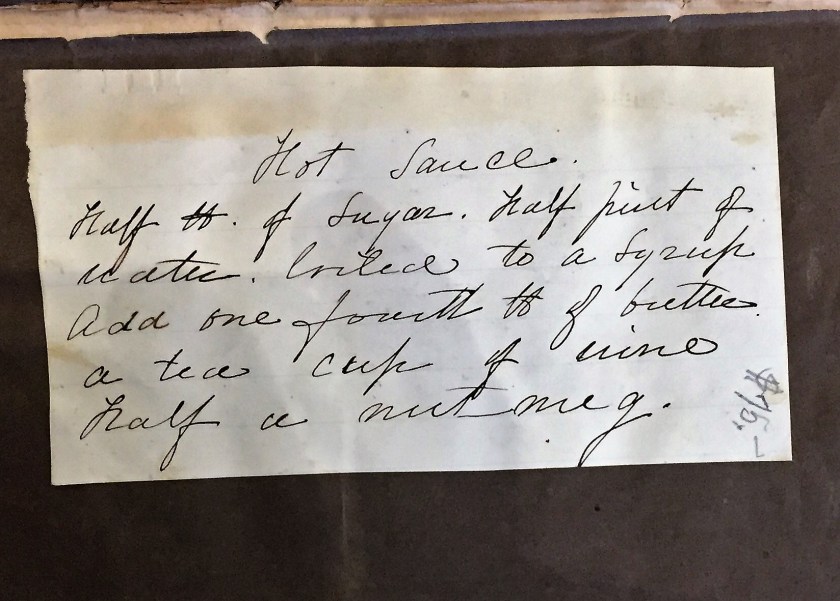

Mary Randolph, a direct descendant of  Mary Randolph is best known as the author of America’s first regional cookbook, “The Virginia House-wife” and known to some, as “The Methodical Cook”.

Mary Randolph is best known as the author of America’s first regional cookbook, “The Virginia House-wife” and known to some, as “The Methodical Cook”. Mary Randolph, wife of David Meade Randolph, was an early advocate of the now-common use of herbs, spices and wines in cooking.

Mary Randolph, wife of David Meade Randolph, was an early advocate of the now-common use of herbs, spices and wines in cooking.

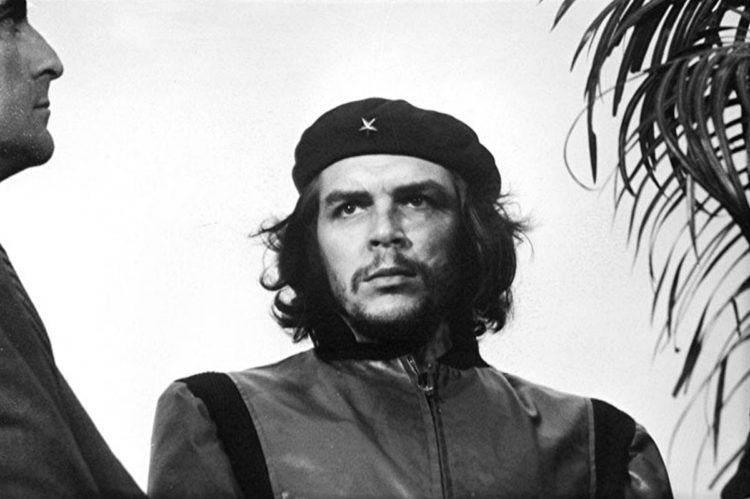

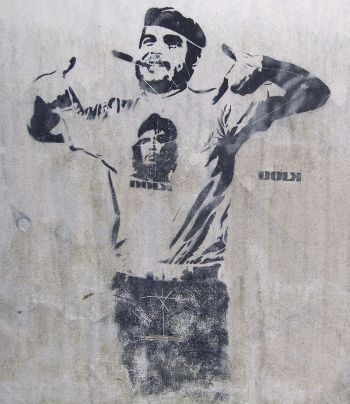

Ernesto Guevara trained and motivated firing squads credited with the summary execution of 16,000 Cubans or more, since the Castro brothers swept out of the Sierra Maestro Mountains in 1959. It was around this time he acquired the nickname “Che” from an odd fondness for the verbal filler che, not unlike the Canadian English “eh” or some Americans’ fondness for the punctuating syllable “Right?”

Ernesto Guevara trained and motivated firing squads credited with the summary execution of 16,000 Cubans or more, since the Castro brothers swept out of the Sierra Maestro Mountains in 1959. It was around this time he acquired the nickname “Che” from an odd fondness for the verbal filler che, not unlike the Canadian English “eh” or some Americans’ fondness for the punctuating syllable “Right?” Numbers are surprisingly inexact but Guevara is believed personally responsible for the murder of hundreds if not thousands, in the name of “Revolutionary Justice”. Guevara himself described in his diary, the murder of peasant guide Eutimio Guerra:

Numbers are surprisingly inexact but Guevara is believed personally responsible for the murder of hundreds if not thousands, in the name of “Revolutionary Justice”. Guevara himself described in his diary, the murder of peasant guide Eutimio Guerra:

While Che himself made no secret of his blood-lust, Western Liberals appear pathologically incapable of regarding the man’s history, as it really was.

While Che himself made no secret of his blood-lust, Western Liberals appear pathologically incapable of regarding the man’s history, as it really was. “Crazy with fury I will stain my rifle red while slaughtering any enemy that falls in my hands! My nostrils dilate while savoring the acrid odor of gunpowder and blood. With the deaths of my enemies I prepare my being for the sacred fight and join the triumphant proletariat with a bestial howl!…Hatred as an element of struggle; unbending hatred for the enemy, which pushes a human being beyond his natural limitations, making him into an effective, violent, selective, and cold-blooded killing machine. This is what our soldiers must become” – Ernesto Ché Guevara

“Crazy with fury I will stain my rifle red while slaughtering any enemy that falls in my hands! My nostrils dilate while savoring the acrid odor of gunpowder and blood. With the deaths of my enemies I prepare my being for the sacred fight and join the triumphant proletariat with a bestial howl!…Hatred as an element of struggle; unbending hatred for the enemy, which pushes a human being beyond his natural limitations, making him into an effective, violent, selective, and cold-blooded killing machine. This is what our soldiers must become” – Ernesto Ché Guevara For many of us, then-President Obama’s March 21, 2016 moment in Havana, Cuba defies understanding, unfolding as it did under a ten-story image of Che Guevara.

For many of us, then-President Obama’s March 21, 2016 moment in Havana, Cuba defies understanding, unfolding as it did under a ten-story image of Che Guevara.

On January 17, 1968, Unit 124 infiltrated the 2½ mile demilitarized zone (DMZ), cutting the wire and entering South Korea. Their mission was to assassinate ROK President Park Chung-hee in his home, the Executive Mansion equivalent to the United States’ own White House, the “Pavilion of Blue Tiles” known as “Blue House”.

On January 17, 1968, Unit 124 infiltrated the 2½ mile demilitarized zone (DMZ), cutting the wire and entering South Korea. Their mission was to assassinate ROK President Park Chung-hee in his home, the Executive Mansion equivalent to the United States’ own White House, the “Pavilion of Blue Tiles” known as “Blue House”.

29 commandos were killed or committed suicide. One escaped, back to North Korea. Only one, Kim Shin-jo, was captured alive.

29 commandos were killed or committed suicide. One escaped, back to North Korea. Only one, Kim Shin-jo, was captured alive.

You must be logged in to post a comment.