When he was little, his neighbors must have thought he was a bad kid. His first arrest came at age 12, when he and some friends were caught stealing brass from a foundry. There were other episodes between 1932 and ’37: petty theft, breaking & entering, and disturbing the peace. He was sent to prison in 1939, for stealing a car.

Edward Donald “Eddie” Slovik was paroled in 1942, his criminal record rendering him 4F. “Registrant not acceptable for military service”. He took a job at the Montella Plumbing & Heating company in Dearborn, Michigan, where he met bookkeeper Antoinette Wisniewski, the woman who would later become his wife.

There the couple may have ridden out WWII, but the war was consuming manpower at a rate unprecedented in history. Shortly after the couple’s first anniversary, Slovik was re-classified 1A, fit for service, and drafted into the Army. Arriving in France on August 20, 1944, he was part of a 12-man replacement detachment, assigned to Company G of the 109th Infantry Regiment, US 28th Infantry Division.

There the couple may have ridden out WWII, but the war was consuming manpower at a rate unprecedented in history. Shortly after the couple’s first anniversary, Slovik was re-classified 1A, fit for service, and drafted into the Army. Arriving in France on August 20, 1944, he was part of a 12-man replacement detachment, assigned to Company G of the 109th Infantry Regiment, US 28th Infantry Division.

Slovik and a buddy from basic training, Private John Tankey, became separated from their detachment during an artillery attack and spent the next six weeks with Canadian MPs. It was around this time that Private Slovik decided he “wasn’t cut out for combat”.

The rapid movement of the army during this period caused difficulty for many replacements attempting to find their units. Edward Slovik and John Tankey finally caught up with the 109th on October 7. The following day, Slovik asked his company commander Captain Ralph Grotte for reassignment to a rear unit, saying he was “too scared” to be part of a rifle company. Grotte refused, confirming that, were he to run away, such an act would constitute desertion.

And desert, he did. Eddie Slovik left his unit on October 9, despite Private Tankey’s protestations that he should stay. “My mind is made up”, he said. Slovik walked several miles until he found an enlisted cook, to whom he presented the following note.

“I, Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik, 36896415, confess to the desertion of the United States Army. At the time  of my desertion we were in Albuff [Elbeuf] in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my fox hole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.P. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE. — Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415”.

of my desertion we were in Albuff [Elbeuf] in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my fox hole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.P. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE. — Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415”.

Slovik was repeatedly ordered to tear up the note and rejoin his unit, and there would be no consequences. Each time, he refused. The stockade didn’t scare him. He’d been in prison before and it was better than the front lines. Beside that, he was already an ex-con. A dishonorable discharge was hardly going to change anything in an already dim future. Finally, instructed to write a second note on the back of the first acknowledging the legal consequences of his actions, Eddie Slovik was taken into custody.

1.7 million courts-martial were held during WWII, 1/3rd of all the criminal cases tried in the United States during the period. The death penalty was rarely imposed. When it was, it was almost always in cases of rape or murder.

2,864 US Army personnel were tried for desertion between January 1942 and June 1948. Courts-martial handed down death sentences to 49 of them, including Eddie Slovik. Division commander Major General Norman Cota approved the sentence. “Given the situation as I knew it in November, 1944,” he said, “I thought it was my duty to this country to approve that sentence. If I hadn’t approved it–if I had let Slovik accomplish his purpose–I don’t know how I could have gone up to the line and looked a good soldier in the face.”

On December 9, Slovik wrote to Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, pleading for clemency. Desertion was a systemic problem at this time. Particularly after the surprise German offensive coming out of the frozen Ardennes Forest on December 16, an action that went into history as the Battle of the Bulge. Eisenhower approved the execution order on December 23, believing it to be the only way to discourage further desertions.

On December 9, Slovik wrote to Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, pleading for clemency. Desertion was a systemic problem at this time. Particularly after the surprise German offensive coming out of the frozen Ardennes Forest on December 16, an action that went into history as the Battle of the Bulge. Eisenhower approved the execution order on December 23, believing it to be the only way to discourage further desertions.

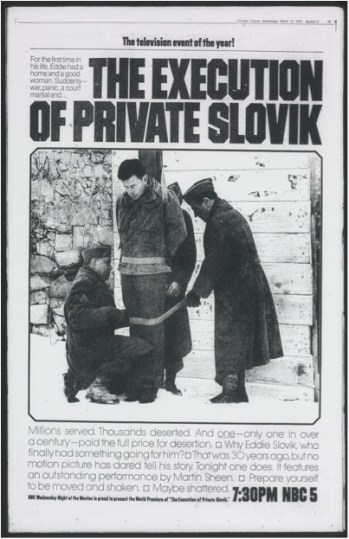

His uniform stripped of all insignia with an army blanket draped over his shoulders, Slovik was brought to the place of execution near the Vosges Mountains of France. “They’re not shooting me for deserting the United States Army”, he said, “thousands of guys have done that. They just need to make an example out of somebody and I’m it because I’m an ex-con. I used to steal things when I was a kid, and that’s what they are shooting me for. They’re shooting me for the bread and chewing gum I stole when I was 12 years old.”

Army Chaplain Father Carl Patrick Cummings said, “Eddie, when you get up there, say a little prayer for me.” Slovik said, “Okay, Father. I’ll pray that you don’t follow me too soon”. Those were his last words. A soldier placed the black hood over his head. The execution was carried out by firing squad. It was 10:04am local time, January 31, 1945.

Edward Donald Slovik was buried in Plot E of the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery, his marker bearing a number instead of his name. Antoinette Slovik received a telegram informing her that her husband had died in the European Theater of the war and a letter, instructing her to return a $55 allotment check. She wouldn’t learn about the execution for another nine years.

In 1987, President Ronald Reagan ordered the repatriation of Slovik’s remains. He was re-interred at Detroit’s Woodmere Cemetery next to Antoinette who had gone to her final rest, eight years earlier.

In all theaters of WWII, the United States military executed 102 of its own, almost always for the unprovoked rape and/or murder of civilians. From the Civil War to this day, the execution of Private Slovik was the only time a death sentence was carried out for the crime of desertion. At least one member of the tribunal which condemned him to death, would come to see it as a miscarriage of justice.

Nick Gozik of Pittsburg passed away in 2015, at the age of 95. He was there in 1945, a fellow soldier called to witness the execution. “Justice or legal murder”, he said, “I don’t know, but I want you to know I think he was the bravest man in that courtyard that day…All I could see was a young soldier, blond-haired, walking as straight as a soldier ever walked. I thought he was the bravest soldier I ever saw.”

Nick Gozik of Pittsburg passed away in 2015, at the age of 95. He was there in 1945, a fellow soldier called to witness the execution. “Justice or legal murder”, he said, “I don’t know, but I want you to know I think he was the bravest man in that courtyard that day…All I could see was a young soldier, blond-haired, walking as straight as a soldier ever walked. I thought he was the bravest soldier I ever saw.”

Very interesting Rick. This one would certainly open up the debate; arguably military justice is the law of the military and you abide by that knowing the consequences if you don’t. However, if the military, or the government, are going to be selective in who they apply it too, then it becomes more personal and less of a law. This begs the question why was he shot and not any of the others? Perhaps it was because of his record and not the fact that he deserted his unit.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That seems to be the impression Eddie himself drew from the experience. Seems like the stars all lined up on the wrong side for this guy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, that was an interesting one, Rick. Beautifully told, as usual. On the one hand, I think no one who hasn’t experienced combat is qualified to judge something like this; on the other hand, I instinctively disliked Private Slovik . But my jury is out on judicial murder and, trying to set aside the dubious morality of killing this man, it is hard to see what purpose it served.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your kind and generous comments, Mike. I think we had a similar impression from this story. I too have never experienced combat on behalf of my country and for that reason, have not earned the right to sit in judgment.

LikeLike

I read this earlier and cannot get it out of my mind. I know desertion is bad…I get that totally…no way can it be condoned.

I’m not experienced in the military so I could be off base. Isn’t it more dangerous to have someone completely frozen and risking his life and not to mention his platoon?

LikeLiked by 1 person

No question about it Max. This one’s a tough story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I did not know this story. I did not know that “desertion was a systemic problem at this time (in WWII). Particularly after the surprise German offensive coming out of the frozen Ardennes Forest on December 16, an action that went into history as the Battle of the Bulge. Eisenhower approved the execution order on December 23, believing it to be the only way to discourage further desertions.” Thank you for sharing his story with the rest of us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I learned a lot reading up for this one, myself. Thanks for coming along for the ride.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History.

LikeLiked by 2 people