In the 4th century BC, Hippocrates of Kos identified an upper respiratory infection, characterized by the formation of a leathery white “pseudomembrane” on the tonsils, pharynx, and/or nasal cavities of its victims. Early symptoms resemble a cold or flu in which fever, sore throat, and chills lead to bluish skin coloration, painful swallowing, and difficulty breathing. Late symptoms include cardiac arrhythmia with cranial and peripheral nerve palsies.

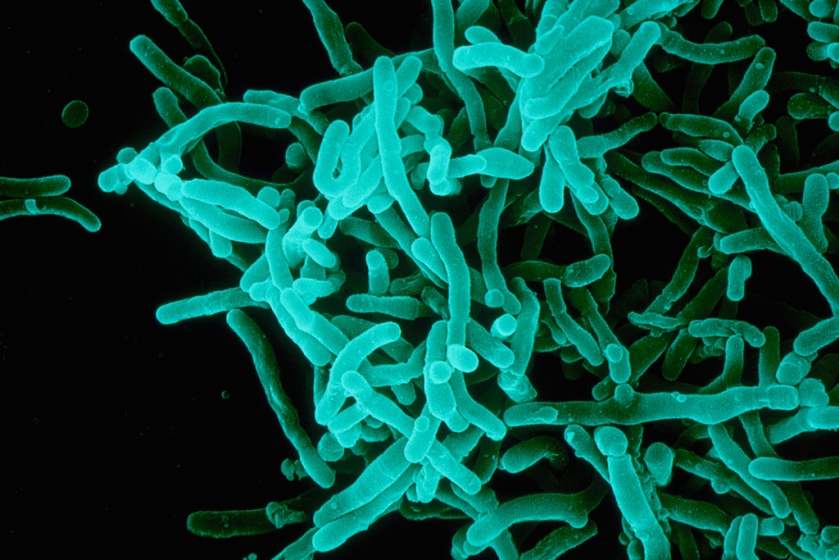

German bacteriologist Friedrich August Johannes Loeffler first identified Corynebacterium diphtheriae in the 1880s, the causal agent of the disease Diphtheria. Within ten years, researchers had developed an effective antitoxin.

Today the disease is all but eradicated in the United States, but diphtheria was once a leading cause of death among children and adults over 40.

Diphtheria is highly contagious and spread by direct physical contact and by breathing aerosolized secretions of its victims. Spain experienced an outbreak of the disease in 1613. To this day the year is remembered as “El Año de los Garotillos”. The Year of Strangulations.

A severe outbreak swept through New England in 1735. In one New Hampshire town, one of every three children under the age of 10 died of the disease. In some cases entire families were wiped out. Noah Webster described the outbreak, saying “It was literally the plague among children. Many families lost three of four children—many lost all”.

Dr. Curtis Welch practiced medicine in Nome, Alaska, in 1925. Several children became ill with what he first diagnosed as tonsillitis. More came down with sore throats, early sufferers beginning to die as Welch observed the pseudomembrane of diphtheria. Dr. Welch had ordered fresh antitoxin the year before, but the shipment hadn’t arrived by the time the ports froze over. By January, all the serum in Nome was expired.

Dr. Curtis Welch practiced medicine in Nome, Alaska, in 1925. Several children became ill with what he first diagnosed as tonsillitis. More came down with sore throats, early sufferers beginning to die as Welch observed the pseudomembrane of diphtheria. Dr. Welch had ordered fresh antitoxin the year before, but the shipment hadn’t arrived by the time the ports froze over. By January, all the serum in Nome was expired.

There were 10,000 living in Nome at the time, 2° south of the Arctic Circle. Welch expected a high mortality rate among the 3,000 or so white inhabitants, but the 7,000 area natives: Central Yupik, Inupiaq, St. Lawrence Island Yupik and American Indians with lineage tied to tribes in the lower 48, likely had no immunity whatsoever. Mortality among these populations could be expected to approach 100%.

Five children had already died by January 25, while Dr. Welch suspected more in the remote native camps. A plea for help went out by telegram and an Anchorage hospital came up with 300,204 units of serum. Enough for 30 patients. A million units would be required. but, perhaps this would be enough to stave off epidemic. Until a larger shipment arrived, in February.

A 20-lb cylinder containing the antitoxin and wrapped in protective fur shipped as far as it could by rail, arriving at Nenana, 674 miles from Nome. Three vintage biplanes were available, but all were in pieces, and none could be started in the sub-arctic cold. The antitoxin would have to go the rest of the way, by dog sled.

On January 27, a US Marshal pounded on the door of Willard J. “Wild Bill” Shannon, begging for his help with the relay to Nome. It was after midnight and −50° Fahrenheit , when Shannon and his nine-dog team received the serum. The temperature had dropped to −62°F by the time the team reached Tolovana, 24 hours later. Shannon himself was hypothermic, with parts of his face turned black with frostbite. Three of his dogs had died on the way, victims of frostbitten lungs.

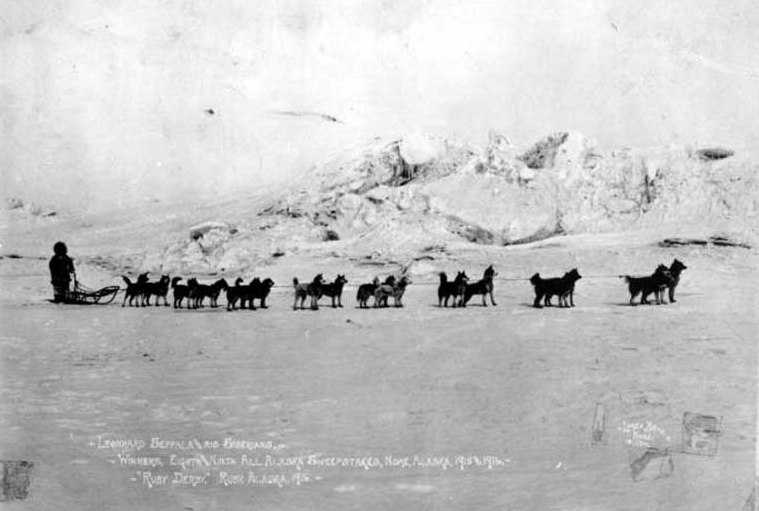

Leonhard Seppala and his team took their turn, departing into gale force winds and zero visibility, with a wind chill of −85°F. With Seppala’s 8-year old-daughter and only child Sigrid at risk for the disease, the stakes could not have been higher.

Up the 5,000′ “Little McKinley”, Seppala gambled on a shortcut across the unstable ice of Norton Sound. The howling gale threatened to break up the ice, stranding the team at sea. Visibility was so poor that Seppala couldn’t see his own “wheel dog” – the dog nearest his sled. The 19-dog team struggled for traction on the glassy skin of the ocean water, returning to the coastline only hours before the ice broke up.

Much of the time, navigation in that black, frozen wilderness was entirely up to Seppala’s lead dog. Most sled dogs are retired by age twelve, especially team leaders, but it was twelve-year-old “Togo”, who was trusted with the lead.

Seppala and Togo ran 170 miles to receive the serum, returning another 91 miles to make the handoff on February 1. Together the pair covered twice as much ground as any other team, over the most dangerous terrain of the “serum run”.

Gunnar Kaasen and his team took the handoff, hitting the trail at 10:00 that night. A massive gust estimated at 80mph upended the sled, pitching musher and serum alike into the snow. Already frostbitten, Kaasen searched in the darkness with bare hands, until he found the cylinder. Covering the last 53 miles overnight, the team reached Front Street, Nome, at 5:30am on February 2. The serum was thawed and ready to use, by noon.

20 mushers and 150 dogs or more had covered 674 miles in 5 days, 7½ hours, a distance that normally took the mail relay 2-3 weeks. Not a single serum ampule was broken.

20 mushers and 150 dogs or more had covered 674 miles in 5 days, 7½ hours, a distance that normally took the mail relay 2-3 weeks. Not a single serum ampule was broken.

With 28 confirmed cases and enough antitoxin for 30, the serum run had held the death toll to no higher than seven.

Doctor Welch suspected as many as 100 or more deaths in the native camps, but the real number will never be known. An untold number of dogs died while completing the run. Several mushers were severely frostbitten.

Gunnar Kaasen and his lead dog “Balto” were hailed as heroes of the serum run, the dog becoming the most popular canine celebrity in the country, after Rin Tin Tin. There was a nine-month vaudeville tour, and Hollywood produced a 30-minute silent film, “Balto’s Race to Nome,” starring himself in the lead role.

A bronze likeness was erected in New York’s Central Park in 1925, with Balto in attendance. The statue stands there to this day, though Kaasen’s lead is depicted wearing Togo’s “colors” (awards).

Balto’s fame was a source of considerable bitterness for Leonhard Seppala, who felt that Kaasen’s 53-mile run was nothing compared with his own 261, Kaasen’s lead little more than a “freight dog”. The statue was particularly galling. “It was almost more than I could bear” he said, “when the ‘newspaper dog’ Balto received a statue for his ‘glorious achievements’”.

Togo lived another four years though the serum run rendered him lame, never again able to run. The real hero of the serum run spent the last years of his life in Poland Spring, Maine, and passed away at the ripe old age of 16.

Wild Bill Shannon disappeared in 1937, while prospecting for gold. His bones were discovered four years later, perhaps a victim of exposure, or perhaps yet another “close call”, with a grizzly bear.

Leonhard Seppala was in his old age in 1960, when he recalled his lead dog on the serum run. “I never had a better dog than Togo. His stamina, loyalty and intelligence could not be improved upon. Togo was the best dog that ever traveled the Alaska trail.”

Today, the memory of the 1925 serum run lives on in the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, held every March and run over much of the same terrain as the ‘Great Race of Mercy’. Togo himself is stuffed and mounted, standing watch at the Iditarod museum headquarters, in Wasilla, Alaska.

Afterward

Despite the decrepit condition of those three biplanes, pilots and mechanics thought they could have one ready to go, in three days. The challenge was immense. Ethylene Glycol wouldn’t be used as an automotive anti-freeze until the following year, and older methods such as Methyl Alcohol wrought havoc on internal engine components.

“The once tight fabric covering the wings and fuselage was weak from all the rough landings as well as the wind and rain. Dirt and oil caked the engine and prop. Wires for the rudders and elevators hung from the sides of the fuselage.” Even in such disrepair, the pilots and mechanics thought one of the planes could be ready to go Nome in just three days, a flight they thought would take no more than 6-hours”.

If unsuccessful, all would be lost. Pilot, aircraft and serum.

The decision was a high stakes gamble, falling in the end to Alaska Governor Scott Bone, who decided on the twenty-team relay. Good thing, too. Multiple efforts to get one of those aircraft in shape for the second shipment, failed.

The Salisbury cousins Gay and Laney tell the tale in a harrowing account called The Cruelest Miles, if you’re interested in more reading. I haven’t gotten to mine yet, but it sounds like a good read.

674 miles in that amount of time…with sleds, dogs, and that weather. The dedication is staggering. The good Lord didn’t bless me with a sense of direction…I can’t imagine how they found their way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amen to that, Max. More than anyone, I think it was Togo who found the way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Dave For Wyoming.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A fascinating story. At least as potent, as the great stories of polar exploration!

LikeLike