“Sitzkrieg”. “Phony War”. Those were the terms used to describe the September 1939 to May 1940 period, when neither side of what was to become World War 2, was yet prepared to launch a major ground war against the other.

The outbreak of “The Great War” twenty-five years earlier, was a different story. Had you been alive in August of 1914, you could have witnessed what might be described as the simultaneous detonation, of a continent. France alone suffered 140,000 casualties over the four day “Battle of the Frontiers”, where the River Sambre met the Meuse. 27,000 Frenchmen died in a single day, August 22, in the forests of the Ardennes and Charleroi.

The British Expeditionary Force escaped annihilation on August 22-23, only by the intervention of mythic angels, at a place called Mons. In the East, a Russian army under General Alexander Samsonov was encircled and so thoroughly shattered at Tannenberg, that German machine gunners were driven to insanity at the damage inflicted by their own guns, on the milling and helpless masses of Russian soldiers. Only 10,000 of the original 150,000 escaped death, destruction or capture. Samsonov himself walked into the woods, and shot himself.

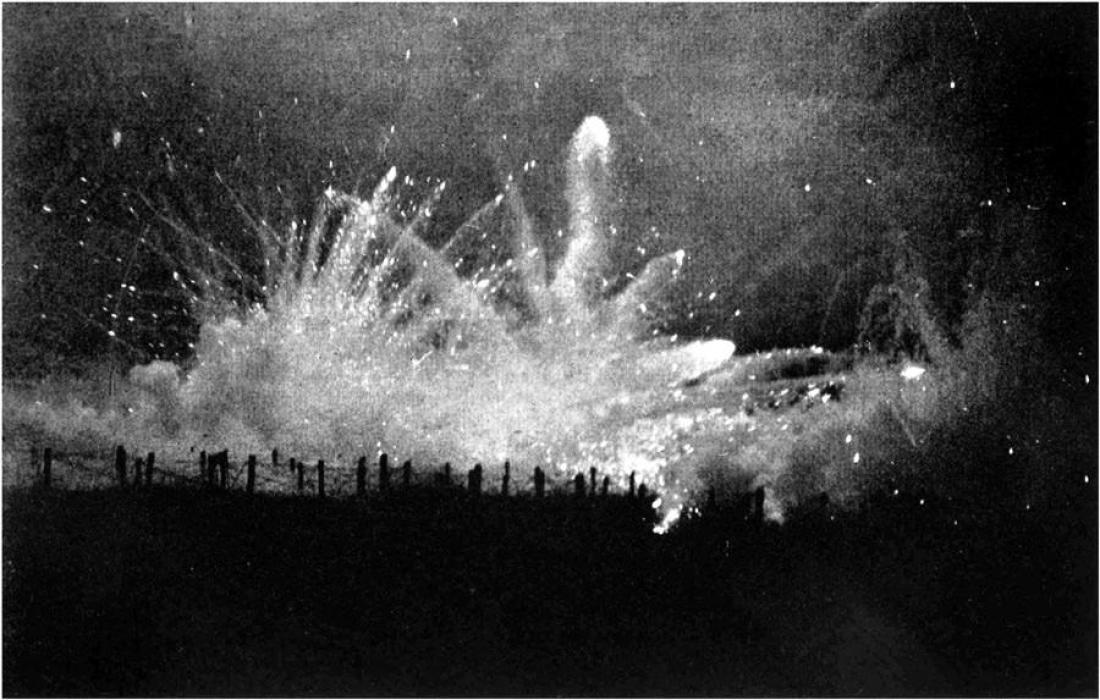

The “Race to the Sea” of mid-September to late October was more a series of leapfrog movements and running combat, in which the adversaries tried to outflank one another. This would be some of the last major movement of the Great War, ending in the apocalypse of Ypres.

When governments make war, It’s the everyday John and the Nigel down the street, the Fritz, the Ivan and the Pierre next door, who must do the fighting, and the bleeding, and the dying.

The battle for the medieval textile town of Leper, most of the battle maps were drawn in French and so we know the place as “Ypres”, began on October 20 and lasted about three weeks, pitting a massive German force of some 600,000 against a quarter-million French, 100,000 British, and 65,000 Belgians.

A million men had been brought to this place, for the purpose of killing each other. The first Battle for Ypres, (there would be others), was the greatest clash in history, or one of them, bringing together more manpower and more firepower than entire wars of the previous century. The losses are hard to get your head around. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) alone suffered 56,000 casualties, including 8,000 killed, 30,000 maimed and another 18,000 missing, of whom roughly one-third, were dead.

The breakdown is harder to get at for the other combatants but, all in, Germany suffered 135,000 casualties, France 85,000 and Belgium, 22,000. Assuming the same percentage distribution of killed, wounded and missing, the three week struggle for Ypres cost the lives of 75,000 men, enough to fill the Athens Olympic Stadium, in Greece.

A story comes down from the fighting of October 22, destined to become German and later Nazi, mythology. French, British and Belgian troops were by this time, digging into the ground to shelter themselves from what Private Ernst Jünger later called the “Storm of Steel”. German Generals, desperate to break through the Allied line and capture Calais and the other French ports on the English Channel, attacked.

German reserve divisions comprised of student volunteers: inexperienced, untrained college students fired with patriotic zeal and singing songs of the Fatherland, marched to the attack against a puny British force, dug into shallow holes around the village of Langemarck. What the BEF lacked this day in numbers, were more than made up, in firepower. Let William Robinson, a volunteer dispatch driver with the British Army, describe what came to be known as the “Kindermord bei Ypern” The Massacre of the Innocents at Ypres.

“The enemy seemed to rise out of the ground and sweep towards us like a great tidal wave, but our machine guns poured steel into them at the rate of six hundred shots per minute, and they’d go down like grass before the scythe… The Germans were climbing over heaps of their own dead, only to meet the same fate themselves.”

Overwhelming German numbers succeeded in forcing the British back and capturing Langemarck on October 22, but the cost was appalling. Some regiments lost 70% of their strength.

Doubt has been cast on the “Myth of Langemarck”, and the tragic bravery of idealistic German boys, happily defending the Fatherland. The numbers of dead and maimed are real enough, but most reservists were in fact comprised of older working class men, not the fresh-faced youth, of the Kindermord. Be that as it may, a story must be told. Excuses must be made to the home team, for the crushing failure of the War of Movement, and the four-year war of attrition, to follow.

Doubt has been cast on the “Myth of Langemarck”, and the tragic bravery of idealistic German boys, happily defending the Fatherland. The numbers of dead and maimed are real enough, but most reservists were in fact comprised of older working class men, not the fresh-faced youth, of the Kindermord. Be that as it may, a story must be told. Excuses must be made to the home team, for the crushing failure of the War of Movement, and the four-year war of attrition, to follow.

Two short months later, some of these same men would step out of their trenches and across the frozen fields of Flanders, to shake the hand of the man he’d been sent there, to kill. The unofficial “Christmas Truce” of 1914 would last a day or two in some sectors and a week or two in others. And then it was back, to the business at hand. For Four. More. Years.

First raised above the town square on October 19, 1774, the flag’s canton featured the Union Jack, on the blood red field of the British Red Ensign. The

First raised above the town square on October 19, 1774, the flag’s canton featured the Union Jack, on the blood red field of the British Red Ensign. The

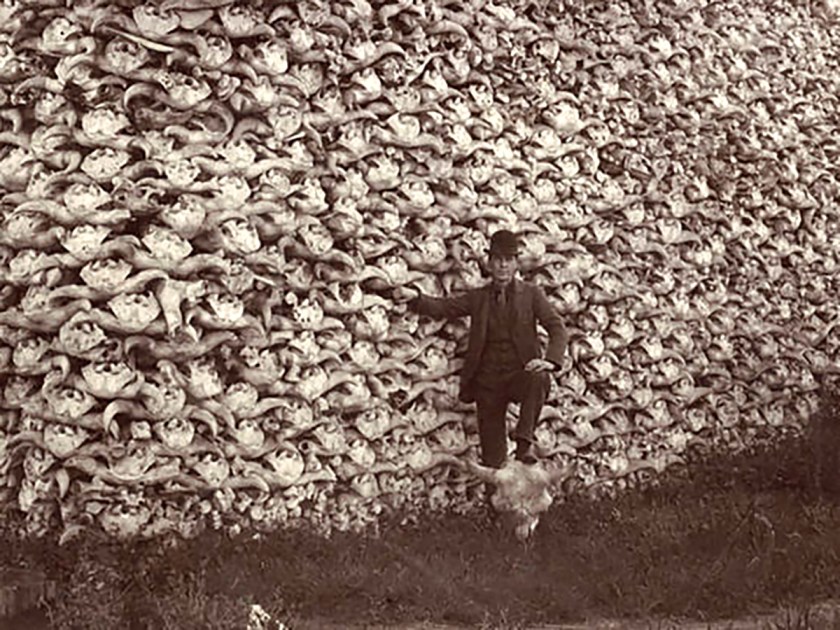

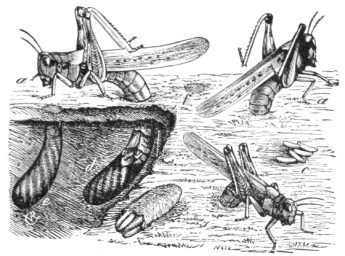

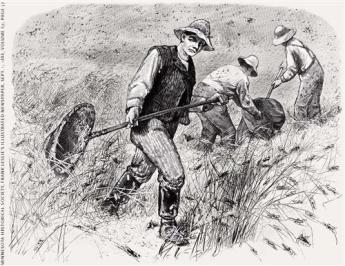

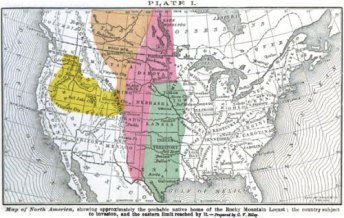

Farmers used gunpowder, fire and water, anything they could think of, to destroy what could only be seen as a plague of biblical proportion. They smeared them with “hopperdozers”, a plow-like device pulled behind horses, designed to knock jumping locusts into a pan of liquid poison or fuel, or even sucking them into vacuum cleaner-like contraptions.

Farmers used gunpowder, fire and water, anything they could think of, to destroy what could only be seen as a plague of biblical proportion. They smeared them with “hopperdozers”, a plow-like device pulled behind horses, designed to knock jumping locusts into a pan of liquid poison or fuel, or even sucking them into vacuum cleaner-like contraptions. And then the locust went away, and no one is entirely certain, why. It is theorized that plowing, irrigation and harrowing destroyed up to 150 egg cases per square inch, in the years between swarms. Great Plains settlers, particularly those alongside the Mississippi river, appear to have disrupted the natural life cycle. Winter crops, particularly wheat, enabled farmers to “beat them to the punch”, putting away stockpiles of food before the pestilence reached the swarming phase.

And then the locust went away, and no one is entirely certain, why. It is theorized that plowing, irrigation and harrowing destroyed up to 150 egg cases per square inch, in the years between swarms. Great Plains settlers, particularly those alongside the Mississippi river, appear to have disrupted the natural life cycle. Winter crops, particularly wheat, enabled farmers to “beat them to the punch”, putting away stockpiles of food before the pestilence reached the swarming phase.

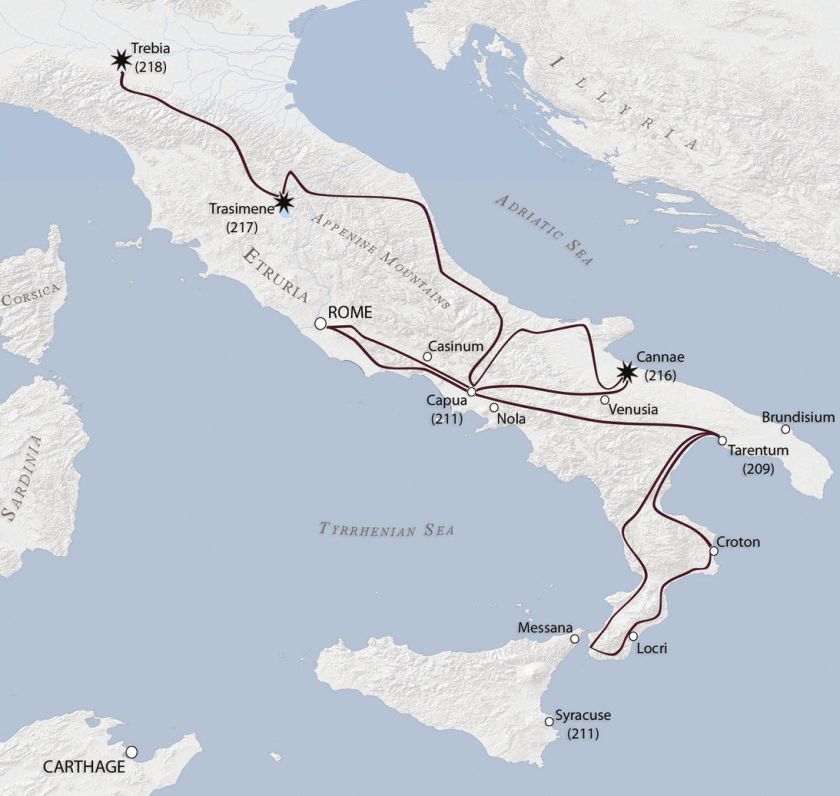

A series of civil wars and other events took place during the first century B.C., ending the Republican period and leaving in its wake an Imperium, best remembered for its long line of dictators.

A series of civil wars and other events took place during the first century B.C., ending the Republican period and leaving in its wake an Imperium, best remembered for its long line of dictators.

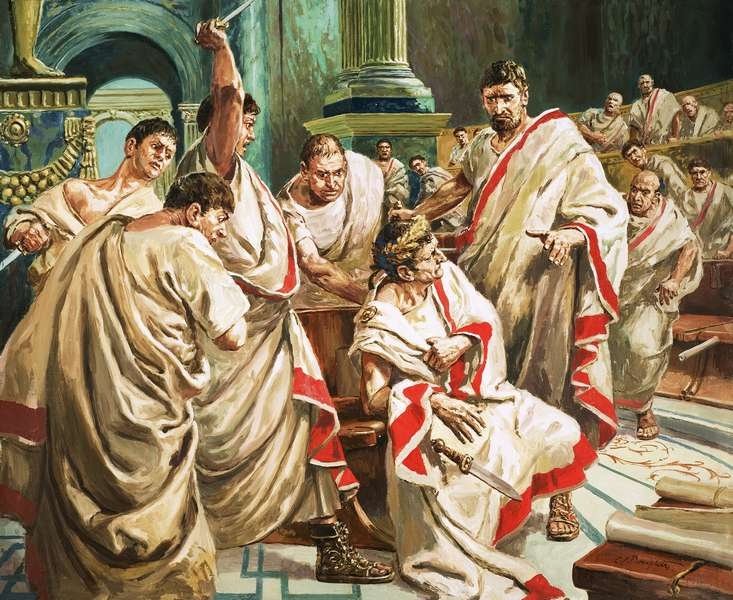

Brutus was 41 on the 15th of March, 44 B.C. The “Ides of March”. Caesar was 56. The Emperor’s dying words are supposed to have been “Et tu, Brute?”, as Brutus plunged the dagger in. “And you, Brutus?” But that’s not what he said. Those words were put into his mouth 1,643 years later, by William Shakespeare.

Brutus was 41 on the 15th of March, 44 B.C. The “Ides of March”. Caesar was 56. The Emperor’s dying words are supposed to have been “Et tu, Brute?”, as Brutus plunged the dagger in. “And you, Brutus?” But that’s not what he said. Those words were put into his mouth 1,643 years later, by William Shakespeare.

The Meux’s Brewery Co Ltd, established in 1764, was a London brewery owned by Sir Henry Meux. What the Times article was describing was a 22′ high monstrosity, held together by 29 iron hoops.

The Meux’s Brewery Co Ltd, established in 1764, was a London brewery owned by Sir Henry Meux. What the Times article was describing was a 22′ high monstrosity, held together by 29 iron hoops. The brewery was located in the crowded slum of St. Giles, where many homes contained several people to the room.

The brewery was located in the crowded slum of St. Giles, where many homes contained several people to the room. One brewery worker was able to save his brother from drowning in the flood, but others weren’t so lucky.

One brewery worker was able to save his brother from drowning in the flood, but others weren’t so lucky. In the days that followed, the crushing poverty of the slum led some to exhibit the corpses of their family members, charging a fee for anyone who wanted to come in and see. In one house, too many people crowded in and the floor collapsed, plunging them all into a cellar full of beer.

In the days that followed, the crushing poverty of the slum led some to exhibit the corpses of their family members, charging a fee for anyone who wanted to come in and see. In one house, too many people crowded in and the floor collapsed, plunging them all into a cellar full of beer.

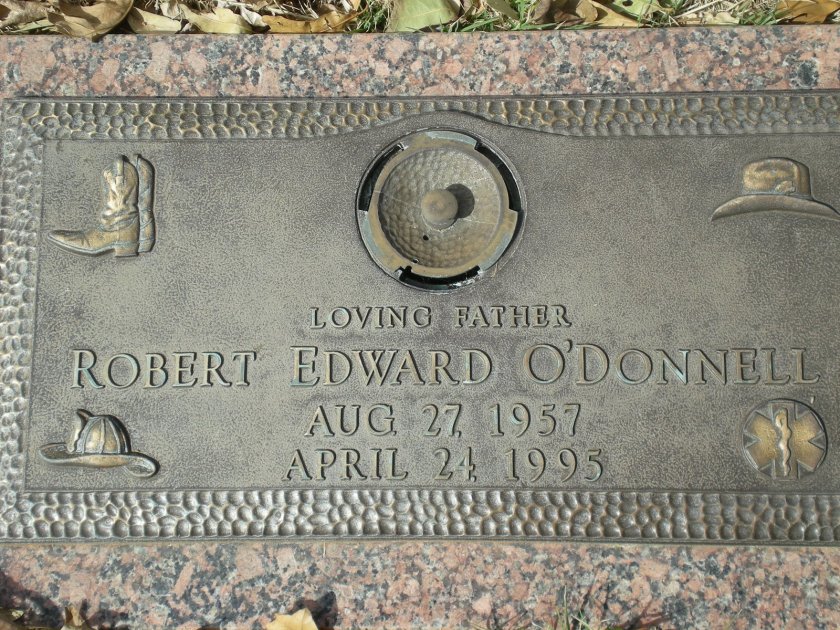

On this day in 1987, Jessica McClure’s life was anything but normal. Frightened and alone, “Baby Jessica” was stuck twenty-two feet down, at the bottom of a well.

On this day in 1987, Jessica McClure’s life was anything but normal. Frightened and alone, “Baby Jessica” was stuck twenty-two feet down, at the bottom of a well.

The sun went down that Wednesday and rose the following day and then it set, and still, the nightmare dragged on.

The sun went down that Wednesday and rose the following day and then it set, and still, the nightmare dragged on.

Margaretha Geertruida Zelle, “M’greet” to family and friends, was born in the Netherlands on August 7, 1876, the eldest of four children.

Margaretha Geertruida Zelle, “M’greet” to family and friends, was born in the Netherlands on August 7, 1876, the eldest of four children.

All things “Oriental” were all the rage in early 1900s Paris. Mata Hari played the more exotic aspects of her background to the hilt, projecting a bold and in-your-face sexuality that was unique and provocative for her time.

All things “Oriental” were all the rage in early 1900s Paris. Mata Hari played the more exotic aspects of her background to the hilt, projecting a bold and in-your-face sexuality that was unique and provocative for her time. The world stood still at the beginning of World War I, but not Mata Hari. Her dancing days were over by 1914, but her neutral Dutch citizenship allowed her to move about without restriction. But not without a price. Mata Hari’s sexual conquests knew no border, naively including officers and government officials of every nationality, and both sides of the Great War.

The world stood still at the beginning of World War I, but not Mata Hari. Her dancing days were over by 1914, but her neutral Dutch citizenship allowed her to move about without restriction. But not without a price. Mata Hari’s sexual conquests knew no border, naively including officers and government officials of every nationality, and both sides of the Great War. Mata Hari’s elderly defense attorney and former lover Edouard Clunet, never really had a chance. He couldn’t cross examine the prosecution’s witnesses, or even directly question his own.

Mata Hari’s elderly defense attorney and former lover Edouard Clunet, never really had a chance. He couldn’t cross examine the prosecution’s witnesses, or even directly question his own.

The harbor at Scapa flow had been home to the British deep water fleet since 1904, a time when the place truly was, all but impregnable. By 1939, anti-aircraft weaponry was all but obsolete, old block ships were disintegrating, and anti-submarine nets were inadequate to the needs of the new war.

The harbor at Scapa flow had been home to the British deep water fleet since 1904, a time when the place truly was, all but impregnable. By 1939, anti-aircraft weaponry was all but obsolete, old block ships were disintegrating, and anti-submarine nets were inadequate to the needs of the new war. The electric torpedoes of the era were highly unreliable, and this wasn’t shaping up to be their night.

The electric torpedoes of the era were highly unreliable, and this wasn’t shaping up to be their night.

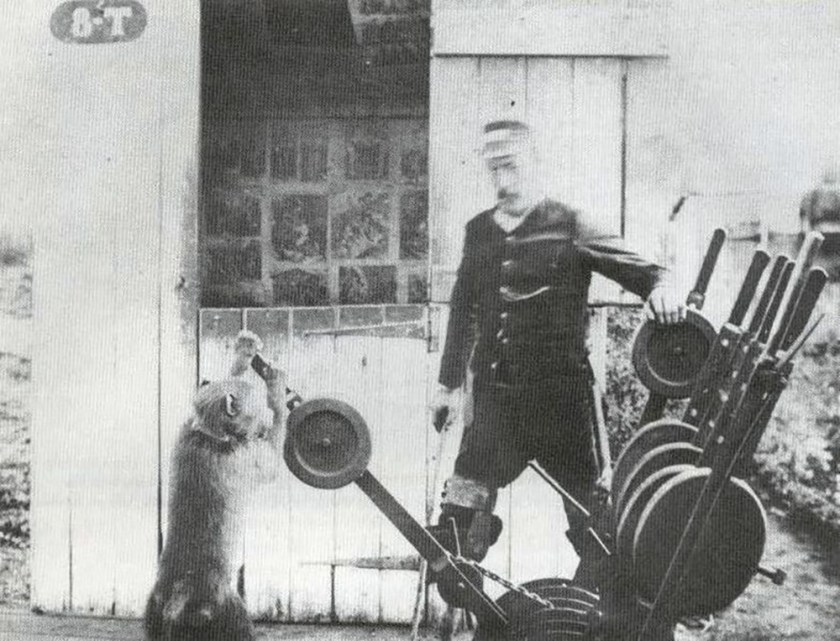

One day at an open-air market, the peg-legged signalman saw something that changed all that. It was a monkey, a Chacma baboon.

One day at an open-air market, the peg-legged signalman saw something that changed all that. It was a monkey, a Chacma baboon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.