For many, the mention of ‘cosmetic surgery’ conjures images of vanity. The never-ending and inevitably fruitless attempt to stave off the years. Add some here and take it off over there. But what of the face left smashed and misshapen, burned or blown half off in service to country?

“Plastic” Surgery, the term comes to us from the Greek Plastikos and first used by the 18th century French surgeon Pierre Desault, has been with us longer than you might expect. Evidence exists of Hindu surgeons performing primitive ‘nose jobs’, as early as BC800-600. The Renaissance-era surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545-1599) developed new methods of reconstruction, using the patient’s own arm skin to replace noses slashed off in swordplay.

“Plastic” Surgery, the term comes to us from the Greek Plastikos and first used by the 18th century French surgeon Pierre Desault, has been with us longer than you might expect. Evidence exists of Hindu surgeons performing primitive ‘nose jobs’, as early as BC800-600. The Renaissance-era surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545-1599) developed new methods of reconstruction, using the patient’s own arm skin to replace noses slashed off in swordplay.

A hillside battle at a place called Hastings changed the world in 1066 yet, if you were on the next hillside, you may not have heard a thing. The industrialized warfare of the 19th and 20th century was vastly different, involving entire populations and inflicting unprecedented levels of destruction on the human form.

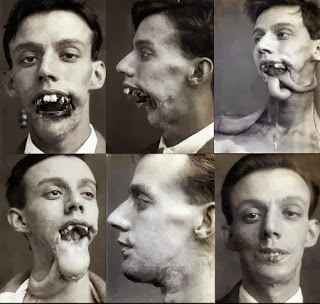

It is beyond horrifying what modern warfare can do to the human form

It’s been said of the American civil war and is no doubt true of any number of conflicts, that a generation of women had to accustom themselves to new ideas of male ‘beauty’. The ‘Great War’ of 1914 – ‘18 was particularly egregious when it came to injuries to the face, neck and arms, as millions of soldiers burrowed into 450-mile-long trench lines to escape what German Private Ernst Jünger described as the “Storm of Steel”.

In the Battle of Verdun, German forces used 1,200 guns firing 2.5 million shells supplied by 1,300 ammunition trains to attack their Allied adversary on the First Day, alone.

For every soldier killed in the Great War, two returned home, maimed. Artillery was especially malevolent, with “drumfire” so rapid as to resemble the rat-a-tat-tat of drums, each blast sending thousands of jagged pieces of metal, shrieking through the air.

For many, severe facial disfigurement was a fate worse than amputation. Worse than death, even. To have been grievously wounded in service to country and return home to be treated not as a wounded warrior, but as something hideous.

The untold human misery of having been turned into a monster, misshapen and ugly. For these men, life often became one of ostracism and loneliness. The painful stares of friends and strangers alike, repelled by such disfiguration, offtimes lead to alcoholism, divorce and suicide.

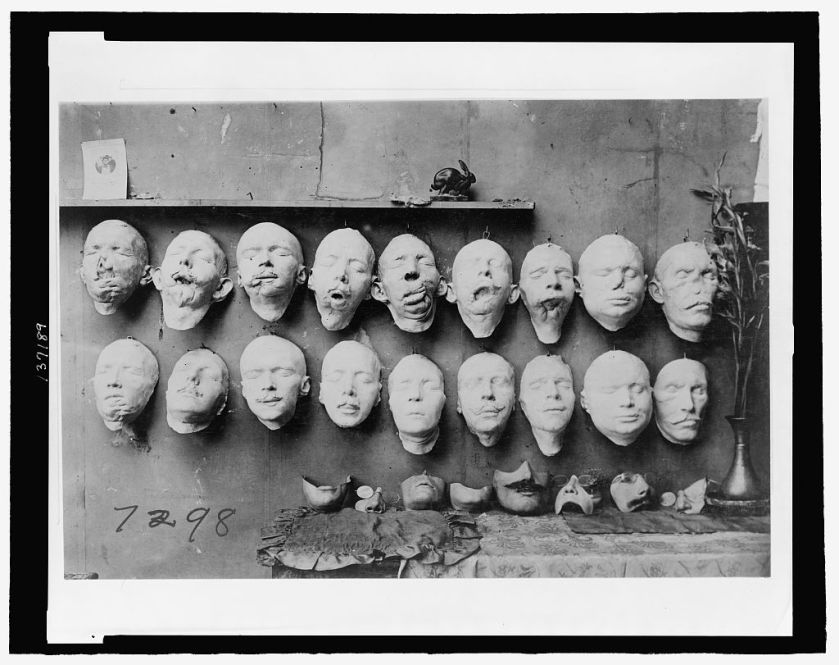

Manchester Massachusetts sculptor Anna Coleman Ladd moved to France in 1917. Inspired by the work of British artist Francis Derwent Wood and his “tin noses shop”, Ladd founded the “Studio for Portrait-Masks” of the Red Cross in Toul, to provide cosmetic prosthetics for men disfigured by the war.

Ladd’s prostheses were uncomfortable to wear, but her services earned her the Légion d’Honneur Croix de Chevalier and the Serbian Order of Saint Sava.

Ladd’s prostheses were uncomfortable to wear, but her services earned her the Légion d’Honneur Croix de Chevalier and the Serbian Order of Saint Sava.

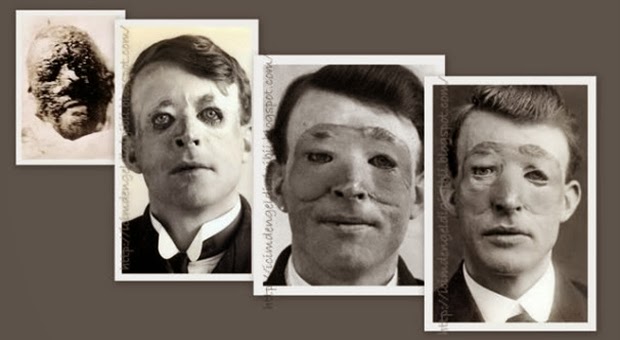

The New Zealand-born otolaryngologist Dr. Harold Gillies was shocked at the human destruction, while working with the French-American dental surgeon Sir August Charles Valadier on new techniques of jaw reconstruction and other maxillofacial procedures.

The sterile medical notation “GSW (gunshot wound) Face” does not begin to prepare the mind for a horror more closely resembling a highway roadkill, than the face of a living man. I left the worst of such images out of this essay. They’re easy enough to find on-line, if you’re interested in seeing them. The medical science is fascinating, but the images are hard to look at.

Dr. Gillies watched the renowned French surgeon Hippolyte Morestin, a man known as “The Father of the Mouths” after multiple breakthroughs in oral surgery, remove a tumor and use the patient’s own jaw-skin, to repair the damage.

Joseph Pickard, of the 5th Northumberland Fusiliers, before and after Dr. Gillies. H/T Daily Mail

Gillies understood the importance of the work, and spoke with British Chief Surgeon Sir William Arbuthnot Lane. The conversation lead to a 1,000-bed facial trauma ward at Queen Mary’s Hospital in Sidcup, Kent, opened in June, 1917.

The largest naval battle of the Great War, the Battle of Jutland, unfolded between May 31 and June 1, 1916, involving 250 ships and some 100,000 men.

The Queen Elizabeth-class battleship HMS Warspite took fifteen direct hits from German heavy shells, at one point having no rudder control and helplessly turning in circles.

Petty Officer Walter Yeo was manning the guns aboard Warspite and received terrible injuries to his face, including the loss of upper and lower eylids, and extensive blast and burn damage to his nose, cheeks and forehead.

Yeo was admitted to Queen Mary’s hospital the following August, where he was treated by Dr. Gillies and believed to be the first recipient of a full facial graft taken from another part of his own body.

Dr. Gillies & Co. developed surgical methods in which rib cartilage is first implanted in foreheads, and then swung down to form the foundational structure of a new nose.

Dr. Gillies & Co. developed surgical methods in which rib cartilage is first implanted in foreheads, and then swung down to form the foundational structure of a new nose.

At a time before antibiotics, tissue grafts could be as dangerous as the trenches themselves. “Tubed pedicles” were developed to get around the problem of infection, where living tissue and its blood supply was rolled into tubes and protected by the natural layer of skin. These tubes of living tissue weren’t pretty to look but were relatively safe from infection. When the patient was ready, new tissue could be “walked” into place, become whole new facial features.

Dr. Harold Gelf Gillies, the Father of modern plastic surgery, performed more than 11,000 such procedures with his colleagues, on over 5,000 individuals. Work continued well after the war and through the mid-twenties, developing new and important surgical techniques.

Dr. Gillies received a knighthood for his work in 1930 and, during the inter-war years, trained many other Commonwealth physicians on his surgical methods. Just in time to send the following generation, off to the next war.

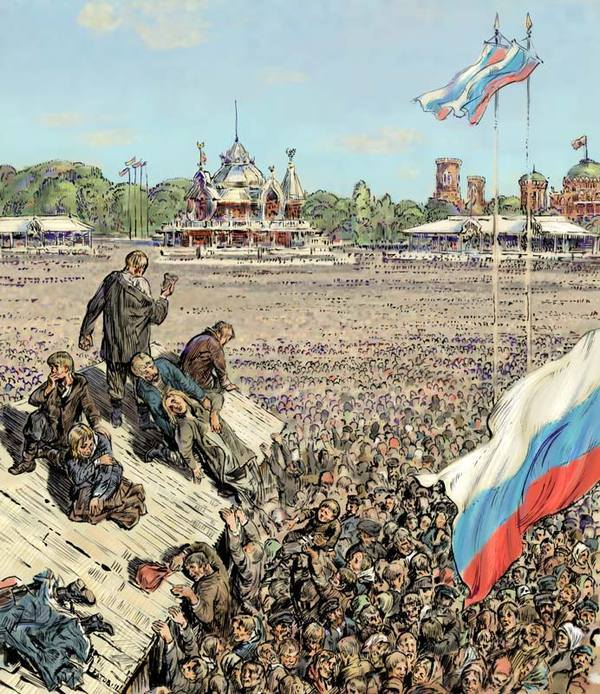

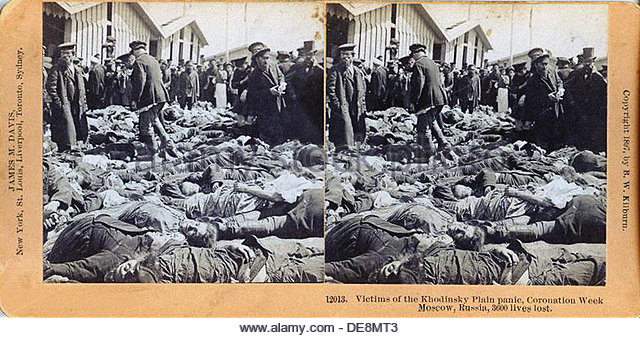

It was customary that gifts be given to the guests of such a celebration. There were commemorative scarves and ornately decorated porcelain cups, bearing the ciphers of Nicholas and Alexandra opposite the double-headed symbol of the Imperial dynasty, the Romanov eagle.

It was customary that gifts be given to the guests of such a celebration. There were commemorative scarves and ornately decorated porcelain cups, bearing the ciphers of Nicholas and Alexandra opposite the double-headed symbol of the Imperial dynasty, the Romanov eagle.

podium was pocked and lined with trenches and pits.

podium was pocked and lined with trenches and pits.

3,662,374 military service certificates were issued to qualifying veterans, bearing a face value equal to $1 per day of domestic service and $1.25 a day for overseas service, plus interest. Total face value of these certificates was $3.638 billion, equivalent to $43.7 billion in today’s dollars and coming to full maturity in 1945.

3,662,374 military service certificates were issued to qualifying veterans, bearing a face value equal to $1 per day of domestic service and $1.25 a day for overseas service, plus interest. Total face value of these certificates was $3.638 billion, equivalent to $43.7 billion in today’s dollars and coming to full maturity in 1945. The Great Depression was two years old in 1932, and thousands of veterans had been out of work since the beginning. Certificate holders could borrow up to 50% of the face value of their service certificates, but direct funds remained unavailable for another 13 years.

The Great Depression was two years old in 1932, and thousands of veterans had been out of work since the beginning. Certificate holders could borrow up to 50% of the face value of their service certificates, but direct funds remained unavailable for another 13 years. This had happened before. Hundreds of Pennsylvania veterans of the Revolution had marched on Washington in 1783, after the Continental Army was disbanded without pay.

This had happened before. Hundreds of Pennsylvania veterans of the Revolution had marched on Washington in 1783, after the Continental Army was disbanded without pay.

Marchers and their families were in their camps on July 28 when Attorney General William Mitchell ordered them evicted. Two policemen became trapped on the second floor of a building when they drew their revolvers and shot two veterans, William Hushka and Eric Carlson, both of whom died of their injuries.

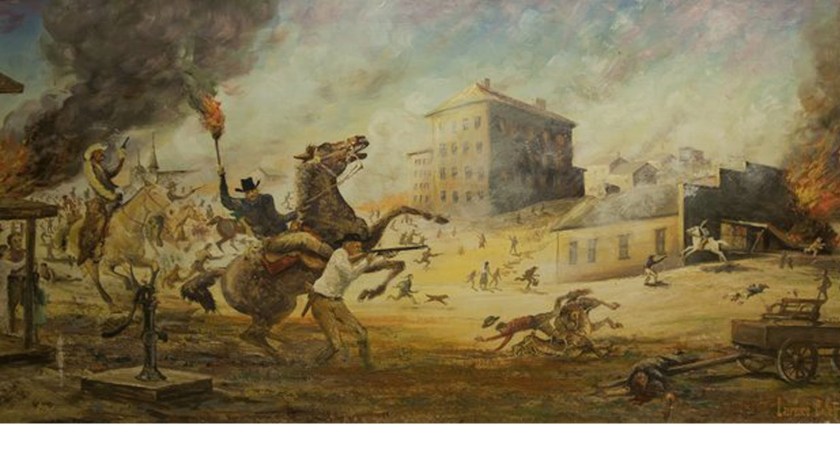

Marchers and their families were in their camps on July 28 when Attorney General William Mitchell ordered them evicted. Two policemen became trapped on the second floor of a building when they drew their revolvers and shot two veterans, William Hushka and Eric Carlson, both of whom died of their injuries. President Herbert Hoover ordered the Army under General Douglas MacArthur to evict the Bonus Army from Washington. 500 Cavalry formed up on Pennsylvania Avenue at 4:45pm, supported by 500 Infantry, 800 police and six battle tanks under the command of then-Major George S. Patton. Civil Service employees came out to watch as bonus marchers cheered, thinking that the Army had gathered in their support.

President Herbert Hoover ordered the Army under General Douglas MacArthur to evict the Bonus Army from Washington. 500 Cavalry formed up on Pennsylvania Avenue at 4:45pm, supported by 500 Infantry, 800 police and six battle tanks under the command of then-Major George S. Patton. Civil Service employees came out to watch as bonus marchers cheered, thinking that the Army had gathered in their support. Bonus marchers fled to their largest encampment across the Anacostia River, when President Hoover ordered the assault stopped. Feeling that the Bonus March was an attempt to overthrow the government, General MacArthur ignored the President and ordered a new attack, the army routing 10,000 and leaving their camps in flames. 1,017 were injured and 135 arrested.

Bonus marchers fled to their largest encampment across the Anacostia River, when President Hoover ordered the assault stopped. Feeling that the Bonus March was an attempt to overthrow the government, General MacArthur ignored the President and ordered a new attack, the army routing 10,000 and leaving their camps in flames. 1,017 were injured and 135 arrested. Then-Major Dwight D. Eisenhower was one of MacArthur’s aides at the time. Eisenhower believed that it was wrong for the Army’s highest ranking officer to lead an action against fellow war veterans. “I told that dumb son-of-a-bitch not to go down there”, he said.

Then-Major Dwight D. Eisenhower was one of MacArthur’s aides at the time. Eisenhower believed that it was wrong for the Army’s highest ranking officer to lead an action against fellow war veterans. “I told that dumb son-of-a-bitch not to go down there”, he said. The bonus march debacle doomed any chance that Hoover had of being re-elected. Franklin D. Roosevelt opposed the veterans’ bonus demands during the election, but was able to negotiate a solution when veterans organized a second demonstration in 1933. Roosevelt’s wife Eleanor was instrumental in these negotiations, leading one veteran to quip: “Hoover sent the army. Roosevelt sent his wife”.

The bonus march debacle doomed any chance that Hoover had of being re-elected. Franklin D. Roosevelt opposed the veterans’ bonus demands during the election, but was able to negotiate a solution when veterans organized a second demonstration in 1933. Roosevelt’s wife Eleanor was instrumental in these negotiations, leading one veteran to quip: “Hoover sent the army. Roosevelt sent his wife”.

Thorne was soon headed to Special Forces, the elite warrior becoming an instructor of skiing, mountaineering, survival and guerrilla tactics.

Thorne was soon headed to Special Forces, the elite warrior becoming an instructor of skiing, mountaineering, survival and guerrilla tactics. As part of the 10th Special Forces Group, Thorne served in a search-and-rescue capacity in West Germany, earning a reputation for courage in operations to recover bodies and classified documents, following a plane in the Zagros Mountains of Iran.

As part of the 10th Special Forces Group, Thorne served in a search-and-rescue capacity in West Germany, earning a reputation for courage in operations to recover bodies and classified documents, following a plane in the Zagros Mountains of Iran.

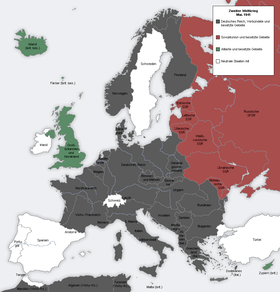

The island nation of Great Britain alone escaped occupation, but British armed forces were shattered and defenseless in the face of the German war machine.

The island nation of Great Britain alone escaped occupation, but British armed forces were shattered and defenseless in the face of the German war machine. Hitler ordered his Panzer groups to resume the advance on May 26, while a National Day of Prayer was declared at Westminster Abbey. That night Winston Churchill ordered “Operation Dynamo”. One of the most miraculous evacuations in military history had begun from the beaches of Dunkirk.

Hitler ordered his Panzer groups to resume the advance on May 26, while a National Day of Prayer was declared at Westminster Abbey. That night Winston Churchill ordered “Operation Dynamo”. One of the most miraculous evacuations in military history had begun from the beaches of Dunkirk. Larger ships were boarded from piers, while thousands waded into the surf and waited in shoulder deep water for smaller vessels. They came from everywhere: merchant marine boats, fishing boats, pleasure craft, lifeboats and tugs. The smallest among them was the 14’7″ fishing boat “Tamzine”, now in the Imperial War Museum.

Larger ships were boarded from piers, while thousands waded into the surf and waited in shoulder deep water for smaller vessels. They came from everywhere: merchant marine boats, fishing boats, pleasure craft, lifeboats and tugs. The smallest among them was the 14’7″ fishing boat “Tamzine”, now in the Imperial War Museum. A thousand copies of navigational charts helped organize shipping in and out of Dunkirk, as buoys were laid around Goodwin Sands to prevent strandings. Abandoned vehicles were driven into the water at low tide, weighted down with sand bags and connected by wooden planks, forming makeshift jetties.

A thousand copies of navigational charts helped organize shipping in and out of Dunkirk, as buoys were laid around Goodwin Sands to prevent strandings. Abandoned vehicles were driven into the water at low tide, weighted down with sand bags and connected by wooden planks, forming makeshift jetties. 7,669 were evacuated on the first full day of the evacuation, May 27, and none too soon. The following day, members of the SS Totenkopf Division marched 100 captured members of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment off to a pit, and machine gunned the lot of them. A group of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment were captured that same day, herded into a barn and murdered with grenades.

7,669 were evacuated on the first full day of the evacuation, May 27, and none too soon. The following day, members of the SS Totenkopf Division marched 100 captured members of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment off to a pit, and machine gunned the lot of them. A group of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment were captured that same day, herded into a barn and murdered with grenades.

Most light equipment and virtually all heavy equipment had to be left behind, just to get what remained of the allied armies out alive. But now, with the United States still the better part of a year away from entering the war, the allies had a military fighting force that would live to fight on.

Most light equipment and virtually all heavy equipment had to be left behind, just to get what remained of the allied armies out alive. But now, with the United States still the better part of a year away from entering the war, the allies had a military fighting force that would live to fight on.

If you’ve raised a child, you are well acquainted with the triumphs and the terrors of giving those little tykes the sword with which they will conquer their world.

If you’ve raised a child, you are well acquainted with the triumphs and the terrors of giving those little tykes the sword with which they will conquer their world.

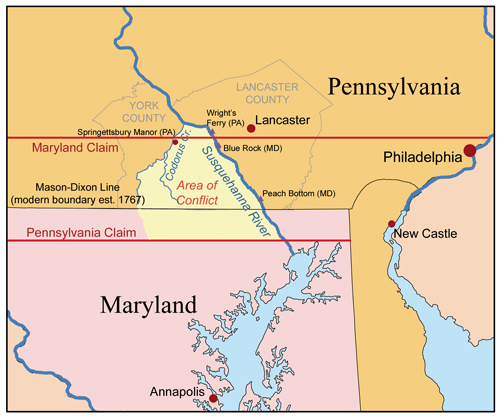

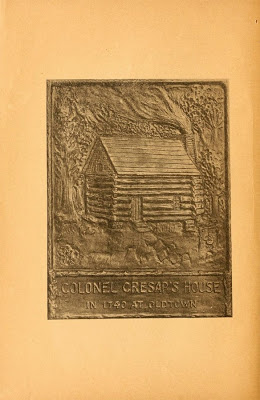

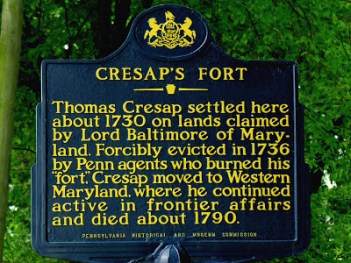

Business was good. By 1730, Wright had applied for a ferry license. With Lord Baltimore fearing a loss of control in the area (read – taxes), Maryland resident Thomas Cresap established a second ferry service up the river. Maryland granted Cresap some 500 acres along the west bank, serenely unconcerned that much of the area was already inhabited by Pennsylvania farmers.

Business was good. By 1730, Wright had applied for a ferry license. With Lord Baltimore fearing a loss of control in the area (read – taxes), Maryland resident Thomas Cresap established a second ferry service up the river. Maryland granted Cresap some 500 acres along the west bank, serenely unconcerned that much of the area was already inhabited by Pennsylvania farmers.

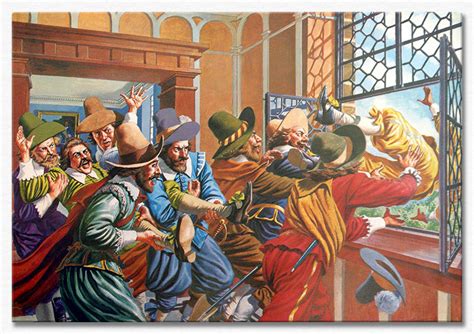

Maryland authorities petitioned George II, King of Great Britain and Ireland, imploring the King to restore order among his subjects. King George’s proclamation of August 18, 1737 instructed the governments of both colonies to cease hostilities. When that failed to stop the fighting, the Crown organized direct negotiations between the two. Peace was signed in London on May 25, 1738, the agreement providing for an exchange of prisoners and a provisional boundary to be drawn fifteen miles south of the southernmost home in Philadelphia, and mandating that neither Maryland nor Pennsylvania “permit or suffer any Tumults Riots or other Outragious Disorders to be committed on the Borders of their respective Provinces.”

Maryland authorities petitioned George II, King of Great Britain and Ireland, imploring the King to restore order among his subjects. King George’s proclamation of August 18, 1737 instructed the governments of both colonies to cease hostilities. When that failed to stop the fighting, the Crown organized direct negotiations between the two. Peace was signed in London on May 25, 1738, the agreement providing for an exchange of prisoners and a provisional boundary to be drawn fifteen miles south of the southernmost home in Philadelphia, and mandating that neither Maryland nor Pennsylvania “permit or suffer any Tumults Riots or other Outragious Disorders to be committed on the Borders of their respective Provinces.”

In 18th century London, it was a bad idea to go out at night. Not without a lantern in one hand, and a club in the other.

In 18th century London, it was a bad idea to go out at night. Not without a lantern in one hand, and a club in the other.

When the Great Depression descended across the land, minor league clubs folded by the bushel. Small town owners were desperate to innovate. The first-ever night game in professional baseball was played on May 2, 1930, when Des Moines, Iowa hosted Wichita for a Western League game.

When the Great Depression descended across the land, minor league clubs folded by the bushel. Small town owners were desperate to innovate. The first-ever night game in professional baseball was played on May 2, 1930, when Des Moines, Iowa hosted Wichita for a Western League game.

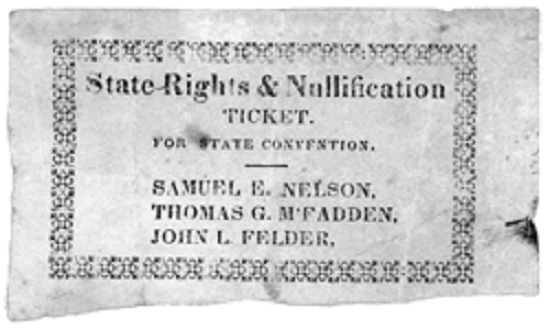

In the first half of the 19th century, 90% of federal government revenue came from tariffs on foreign manufactured goods. A lion’s share of this revenue was collected in the south, with the region’s greater dependence on imported goods. Much of this federal largesse was spent in the north, with the construction of railroads, canals and other infrastructure.

In the first half of the 19th century, 90% of federal government revenue came from tariffs on foreign manufactured goods. A lion’s share of this revenue was collected in the south, with the region’s greater dependence on imported goods. Much of this federal largesse was spent in the north, with the construction of railroads, canals and other infrastructure.

The issue of slavery had joined and become so intertwined with ideas of self-determination, as to be indistinguishable.

The issue of slavery had joined and become so intertwined with ideas of self-determination, as to be indistinguishable. In Washington, Republicans backed the anti-slavery side, while most Democrats supported their opponents. On May 20, 1856, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner took to the floor of the Senate and denounced the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Never known for verbal restraint, Sumner attacked the measure’s sponsors Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois (he of the later Lincoln-Douglas debates), and Andrew Butler of South Carolina by name, accusing the pair of “consorting with the harlot, slavery”. Douglas was in the audience at the time and quipped “this damn fool Sumner is going to get himself shot by some other damn fool”.

In Washington, Republicans backed the anti-slavery side, while most Democrats supported their opponents. On May 20, 1856, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner took to the floor of the Senate and denounced the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Never known for verbal restraint, Sumner attacked the measure’s sponsors Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois (he of the later Lincoln-Douglas debates), and Andrew Butler of South Carolina by name, accusing the pair of “consorting with the harlot, slavery”. Douglas was in the audience at the time and quipped “this damn fool Sumner is going to get himself shot by some other damn fool”.

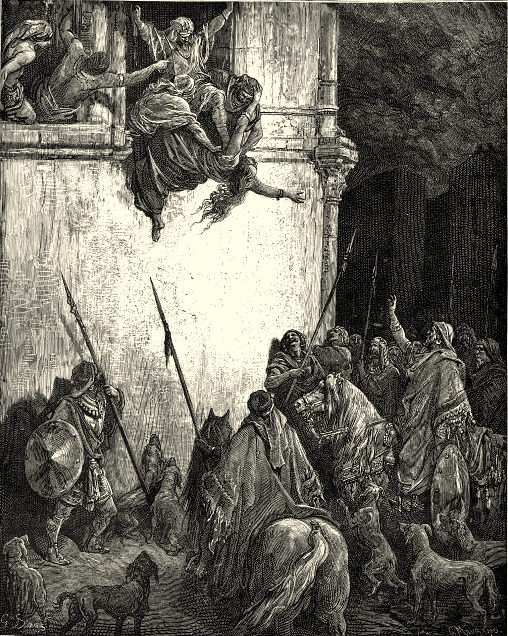

The trio approached Sumner, who was sitting at his desk writing letters. “Mr. Sumner”, Brooks said, “I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine.”

The trio approached Sumner, who was sitting at his desk writing letters. “Mr. Sumner”, Brooks said, “I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine.” In the next two days, a group of unarmed men will be hacked to pieces by anti-slavery radicals, on the banks of

In the next two days, a group of unarmed men will be hacked to pieces by anti-slavery radicals, on the banks of

You must be logged in to post a comment.