The column of British soldiers moved out from Boston late on the 18th, their mission to confiscate the American arsenal at Concord and to capture the Patriot leaders Sam Adams and John Hancock, known to be hiding in Lexington.

Boston Patriot leaders had been preparing for such an event. Sexton Robert John Newman and Captain John Pulling carried two lanterns to the steeple of the Old North church, signaling that the Regulars were crossing the Charles River to Cambridge. Dr. Joseph Warren ordered Paul Revere and Samuel Dawes to ride out and warn surrounding villages and towns, the two soon joined by a third rider, Samuel Prescott. It was Prescott alone who would make it as far as Concord, though hundreds of riders would fan out across the countryside, before the night was through.

The column entered Lexington at sunrise on April 19, bayonets gleaming in the early morning light. Armed with a sorry assortment of weapons, colonial militia was waiting, pouring out of Buckman Tavern and fanning out across the town square. Some weapons were hand made by village gunsmiths and blacksmiths, some decades old, but all were in good working order. Taking positions across the village green to block the soldiers’ line of march, 80 “minutemen” turned and faced 700 of the most powerful military, on the planet.

Words were exchanged and no one knows who fired the first shot. When it was over, eight Lexington men lay dead or dying, another ten wounded. One British soldier was wounded.

Vastly outnumbered, the militia soon gave way, as word spread and militia gathered from Concord to Cambridge. The King’s Regulars never did find the weapons for which they had come, nor did they find Adams or Hancock. There had been too much warning for that.

Regulars would clash with colonial subjects two more times that day, first at Concord Bridge and then in a running fight at a point in the road called “The Bloody Angle”. Finally, hearing that militia was coming from as far away as Worcester, the column turned to the east and began their return march to Boston.

Some British soldiers marched 35 miles over those two days, the final retreat coming under increasing attack from militia members firing from behind stone walls, buildings and trees.

One taking up such a firing position was Samuel Whittemore of Menotomy Village, now Arlington Massachusetts. At 80, Whittemore was the oldest known combatant of the Revolution.

Whittemore took a position by the road, armed with his ancient musket, two dueling pistols and the old cutlass captured years earlier from a French officer whom he explained had “died suddenly”.

Waiting until the last possible moment, Whittemore rose and fired his musket at the oncoming Redcoats: one shot, one kill. Several charged him from only feet away as he drew his pistols. Two more shots, one dead and one mortally wounded. He had barely drawn his sword when the Regulars were on him, a .69 caliber ball fired almost point blank tearing part of his face off, as the butt of a rifle smashed down on his head. Whittemore tried to fend off the bayonet strokes with his sword but he didn’t have a chance. He was run through thirteen times, before he lay still. One for each colony.

The people who came out of their homes to clean up the mess afterward found Whittemore, up on one knee, trying to reload his old musket.

Doctor Nathaniel Tufts treated the old man’s wounds as best he could, but there was nothing he could do. Sam Whittemore was taken home to die in the company of loved ones, which he did. Eighteen years later, at the age of ninety-eight.

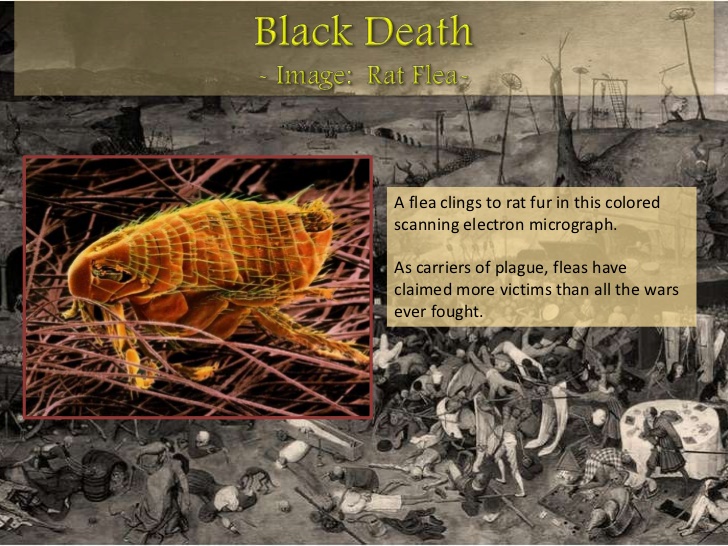

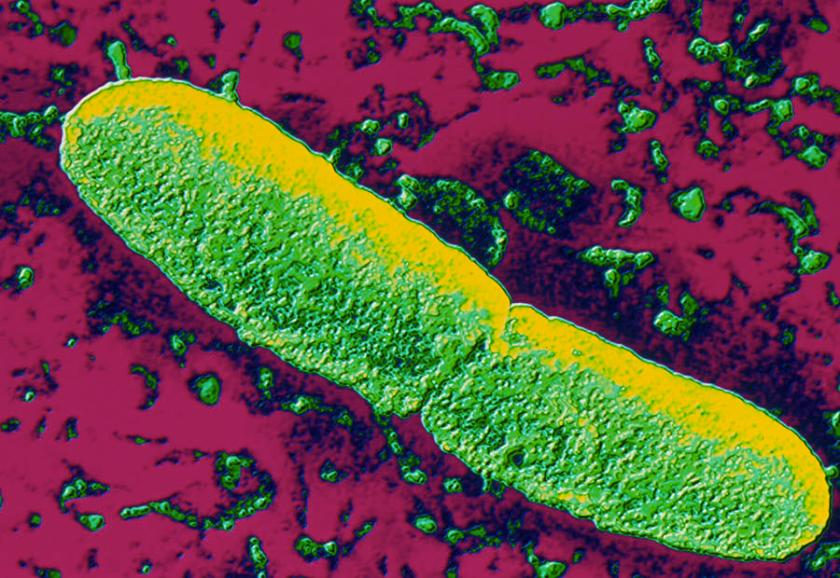

In the early 1330s, a deadly plague broke out on the steppes of Mongolia. The gram-negative bacterium Yersinia Pestis preyed heavily on rodents, the fleas from which would transmit the disease to people, the infection then rapidly spreading to others.

In the early 1330s, a deadly plague broke out on the steppes of Mongolia. The gram-negative bacterium Yersinia Pestis preyed heavily on rodents, the fleas from which would transmit the disease to people, the infection then rapidly spreading to others.

The Black death of 1346-’53 was a catastrophe unparalleled in human history, but it was by no means the last such outbreak. The Third Pandemic began in China in 1855, spreading to Hong Kong and on to British India. In China and India alone the disease killed 12 million people. It then spread to parts of Africa, Europe, Australia, and South America.

The Black death of 1346-’53 was a catastrophe unparalleled in human history, but it was by no means the last such outbreak. The Third Pandemic began in China in 1855, spreading to Hong Kong and on to British India. In China and India alone the disease killed 12 million people. It then spread to parts of Africa, Europe, Australia, and South America.

The body of an elderly Chinese man was discovered in a Chinatown basement. An autopsy found the man to have died of plague. There were more than 18,000 Chinese and another 2,000 Japanese living in the 14-block Chinatown section of the city. Many called for a quarantine of Chinatown, but Chinese citizens objected, as did then-Governor Henry Gage, who tried to sweep the whole outbreak under the carpet. Business interests likewise objected to the quarantine. Except for the Hearst Newspapers, not much was heard about it.

The body of an elderly Chinese man was discovered in a Chinatown basement. An autopsy found the man to have died of plague. There were more than 18,000 Chinese and another 2,000 Japanese living in the 14-block Chinatown section of the city. Many called for a quarantine of Chinatown, but Chinese citizens objected, as did then-Governor Henry Gage, who tried to sweep the whole outbreak under the carpet. Business interests likewise objected to the quarantine. Except for the Hearst Newspapers, not much was heard about it. San Francisco was hit by a massive earthquake on April 18, 1906, followed by a great fire. Thousands of San Franciscans were crowded into refugee camps with an even higher number of rats. For the first time, the disease now jumped the boundaries of Chinatown.

San Francisco was hit by a massive earthquake on April 18, 1906, followed by a great fire. Thousands of San Franciscans were crowded into refugee camps with an even higher number of rats. For the first time, the disease now jumped the boundaries of Chinatown.

Finally, even John D. Rockefeller, Jr., a lifelong teetotaler who contributed $350,000 to the Anti-Saloon League, had to announce his support for repeal.

Finally, even John D. Rockefeller, Jr., a lifelong teetotaler who contributed $350,000 to the Anti-Saloon League, had to announce his support for repeal.

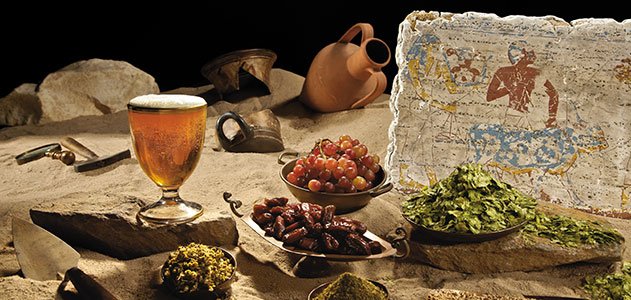

The night before Roosevelt’s law went into effect, April 6, 1933, beer lovers lined up at the doors of their favorite public houses, waiting for their first legal beer in thirteen years. A million and a half barrels of the stuff were consumed the following day, a date remembered today as “National Beer Day”.

The night before Roosevelt’s law went into effect, April 6, 1933, beer lovers lined up at the doors of their favorite public houses, waiting for their first legal beer in thirteen years. A million and a half barrels of the stuff were consumed the following day, a date remembered today as “National Beer Day”.

His two companions were killed. Smith himself was transported to the principle village of Werowocomoco, and brought before the Chief of the Powhatan. His head was forced onto a large stone as a warrior raised a club to smash out his brains. Pocahontas, favorite daughter of Wahunsonacock, rushed in and placed her head on top of his, stopping the execution. Whether it actually happened this way has been debated for centuries. One theory describes the event as an elaborate adoption ceremony, though Smith himself wouldn’t have known that at the time. Afterward, Powhatan told Smith he would “forever esteem him as his son Nantaquoud”.

His two companions were killed. Smith himself was transported to the principle village of Werowocomoco, and brought before the Chief of the Powhatan. His head was forced onto a large stone as a warrior raised a club to smash out his brains. Pocahontas, favorite daughter of Wahunsonacock, rushed in and placed her head on top of his, stopping the execution. Whether it actually happened this way has been debated for centuries. One theory describes the event as an elaborate adoption ceremony, though Smith himself wouldn’t have known that at the time. Afterward, Powhatan told Smith he would “forever esteem him as his son Nantaquoud”. Pocahontas was a pet name, variously translated as “playful one” “my favorite daughter” or “little wanton”. Early in life, she bore the secret name “Matoaka”, meaning “Bright Stream Between the Hills”. Later she was known as “Amonute” which, to the best of my knowledge, has never been translated.

Pocahontas was a pet name, variously translated as “playful one” “my favorite daughter” or “little wanton”. Early in life, she bore the secret name “Matoaka”, meaning “Bright Stream Between the Hills”. Later she was known as “Amonute” which, to the best of my knowledge, has never been translated.

Later descendants of the “Indian Princess” include Glenn Strange, the actor who played Frankenstein in three Universal films during the 1940s, and the character Sam Noonan, the popular bartender in the CBS series, “Gunsmoke”. Astronomer Percival Lowell is a direct descendant of Pocahontas, as is Las Vegas performer Wayne Newton, and former First Lady Edith Wilson, whom some describe as the first female President of the United States. But that must be a story for another day.

Later descendants of the “Indian Princess” include Glenn Strange, the actor who played Frankenstein in three Universal films during the 1940s, and the character Sam Noonan, the popular bartender in the CBS series, “Gunsmoke”. Astronomer Percival Lowell is a direct descendant of Pocahontas, as is Las Vegas performer Wayne Newton, and former First Lady Edith Wilson, whom some describe as the first female President of the United States. But that must be a story for another day.

America’s first war dog, “Stubby”, got there by accident, and served 18 months ‘over there’, participating in seventeen battles on the Western Front.

America’s first war dog, “Stubby”, got there by accident, and served 18 months ‘over there’, participating in seventeen battles on the Western Front. Stubby saw his first action at Chemin des Dames. Since the boom of artillery fire didn’t faze him, he learned to follow the example of ducking when the big ones came close. It became a great game to see who could hit the dugout, first. After a few days, the guys were watching him for a signal. Stubby was always the first to hear incoming fire. We can only guess how many lives were spared by his early warning.

Stubby saw his first action at Chemin des Dames. Since the boom of artillery fire didn’t faze him, he learned to follow the example of ducking when the big ones came close. It became a great game to see who could hit the dugout, first. After a few days, the guys were watching him for a signal. Stubby was always the first to hear incoming fire. We can only guess how many lives were spared by his early warning. After the Armistice, Stubby returned home a nationally acclaimed hero, eventually received by both Presidents Harding and Coolidge. Even General John “Black Jack” Pershing, who commanded the AEF during the war, presented Stubby with a gold medal made by the Humane Society, declaring him to be a “hero of the highest caliber.”

After the Armistice, Stubby returned home a nationally acclaimed hero, eventually received by both Presidents Harding and Coolidge. Even General John “Black Jack” Pershing, who commanded the AEF during the war, presented Stubby with a gold medal made by the Humane Society, declaring him to be a “hero of the highest caliber.”

After a year coaching at Providence College in 1939 and a year playing professional football for the Chicago Cardinals in 1940, Tonelli joined the Army in early 1941, assigned to the 200th Coast Artillery Regiment in Manila.

After a year coaching at Providence College in 1939 and a year playing professional football for the Chicago Cardinals in 1940, Tonelli joined the Army in early 1941, assigned to the 200th Coast Artillery Regiment in Manila. Military forces of Imperial Japan appeared unstoppable in the early months of WWII, attacking first Thailand, then the British possessions of Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong, as well as US military bases in Hawaii, Wake Island, Guam and the Philippines.

Military forces of Imperial Japan appeared unstoppable in the early months of WWII, attacking first Thailand, then the British possessions of Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong, as well as US military bases in Hawaii, Wake Island, Guam and the Philippines. On April 9, 75,000 surrendered the Bataan peninsula, beginning a 65 mile, five-day slog into captivity through the heat of the Philippine jungle. Japanese guards were sadistic. They would beat the marchers and bayonet those too weak to walk. Japanese tanks swerved out of their way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, thousands perished in what came to be known as the Bataan Death March.

On April 9, 75,000 surrendered the Bataan peninsula, beginning a 65 mile, five-day slog into captivity through the heat of the Philippine jungle. Japanese guards were sadistic. They would beat the marchers and bayonet those too weak to walk. Japanese tanks swerved out of their way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, thousands perished in what came to be known as the Bataan Death March. Minutes later, a Japanese officer appeared, speaking perfect English. “Did one of my men take something from you?” “Yes”, Tonelli replied. “My school ring”. “Here,” said the officer, pressing the ring into his hand. “Hide it somewhere. You may not get it back next time”. Tonelli was speechless. “I was educated in America”, the officer said. “At the University of Southern California. I know a little about the famous Notre Dame football team. In fact, I watched you beat USC in 1937. I know how much this ring means to you, so I wanted to get it back to you”.

Minutes later, a Japanese officer appeared, speaking perfect English. “Did one of my men take something from you?” “Yes”, Tonelli replied. “My school ring”. “Here,” said the officer, pressing the ring into his hand. “Hide it somewhere. You may not get it back next time”. Tonelli was speechless. “I was educated in America”, the officer said. “At the University of Southern California. I know a little about the famous Notre Dame football team. In fact, I watched you beat USC in 1937. I know how much this ring means to you, so I wanted to get it back to you”. The hellish 60-day journey aboard the filthy, cramped merchant vessel began in late 1944, destined for slave labor camps in mainland Japan. Tonelli was barely 100 pounds on arrival, his body ravaged by malaria and intestinal parasites. He was barely half the man who once played fullback at Notre Dame Stadium, Soldier Field and Comiskey Park.

The hellish 60-day journey aboard the filthy, cramped merchant vessel began in late 1944, destined for slave labor camps in mainland Japan. Tonelli was barely 100 pounds on arrival, his body ravaged by malaria and intestinal parasites. He was barely half the man who once played fullback at Notre Dame Stadium, Soldier Field and Comiskey Park.

The coming cataclysm would lay waste to a generation, and to a continent.

The coming cataclysm would lay waste to a generation, and to a continent.

On November 11, Armistice Day, the casket was removed from the Rotunda of the Capitol and escorted under military guard to the amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery. In a simple ceremony, President Warren G. Harding bestowed on this unknown soldier the Medal of Honor, and the Distinguished Service Cross.

On November 11, Armistice Day, the casket was removed from the Rotunda of the Capitol and escorted under military guard to the amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery. In a simple ceremony, President Warren G. Harding bestowed on this unknown soldier the Medal of Honor, and the Distinguished Service Cross.

You must be logged in to post a comment.