Following the end of World War II in Europe, the three major allied powers (United States, United Kingdom and the Soviet Union) met at Potsdam, capital of the German federal state of Brandenburg. The series of agreements signed at Cecilienhof Castle and known as the Potsdam agreement built on earlier accords reached at conferences at Tehran, Casablanca and Yalta, addressing issues of German demilitarization, reparations, de-nazification and the prosecution of war criminals.

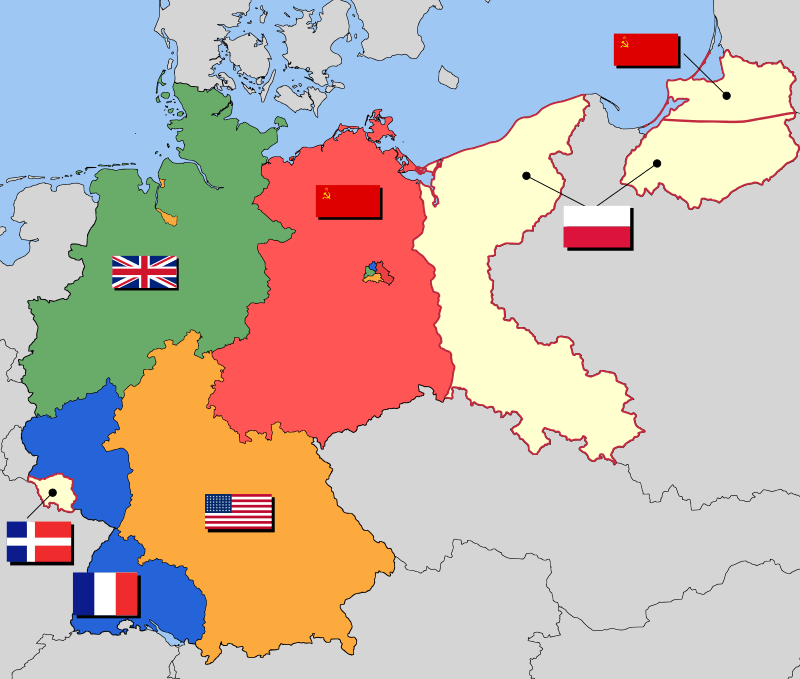

Among the provisions of the Potsdam agreement was the division of defeated Germany into four zones of occupation, rougly coinciding with the then-current locations of allied armies. The former capital city of Berlin was itself partitioned into four zones of occupation. A virtual island located 100 miles inside Soviet-controlled eastern Germany.

During the war, ideological fault lines were suppressed in the mutual desire to destroy the Nazi war machine. These were quick to reassert themselves, in the wake of German defeat. In Soviet-occupied east Germany, factories and equipment were disassembled and transported to the Soviet union, along with technicians, managers and skilled personnel.

Soviet leader Josef Stalin informed German communist leaders in June 1945, of his belief that the United States would withdraw within a year or two. He had his reasons. At that time, the Truman Administration had yet to decide whether American forces would remain in West Berlin past 1949, when an independent West German government was expected to be established.

Stalin would do everything he could to undermine the British position within its zone of occupation, and appears unconcerned about that of the French. He and other Soviet leaders assured visiting Bulgarian and Yugoslavian delegations. In time, all of Germany would be Soviet, and Communist.

The former German capital became the focus of diametrically opposing governing philosophies, and leaders on both sides believed all Europe to be at stake. Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov put it succinctly, “What happens to Berlin, happens to Germany; what happens to Germany, happens to Europe.”

There never was any formal agreement, concerning road and rail access to Berlin through the 100-mile Soviet zone. Western leaders were forced to rely on the “good will” of a regime which had deliberately starved millions of its own citizens to death, in consolidating power.

There never was any formal agreement, concerning road and rail access to Berlin through the 100-mile Soviet zone. Western leaders were forced to rely on the “good will” of a regime which had deliberately starved millions of its own citizens to death, in consolidating power.

With 2.8 million Berliners to feed, clothe and shelter from the elements, Soviet leaders permitted cargo access on only ten trains per day over a single rail line.

Western allies believed the restriction to be only be temporary, but this belief would prove to be sadly mistaken.

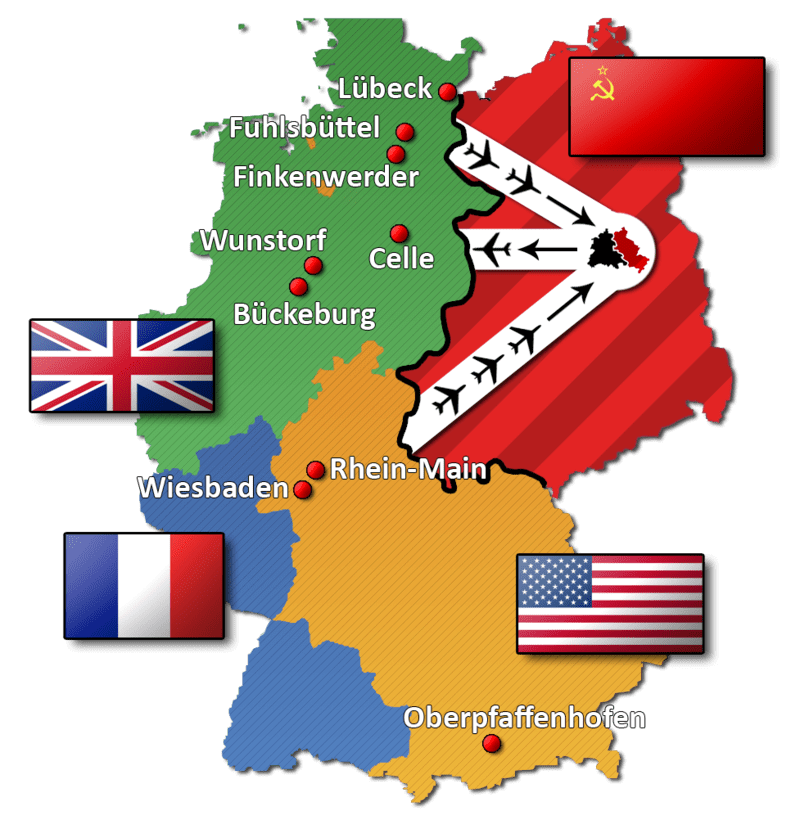

Only three corridors were permitted through Soviet-controlled air space. With millions to feed, the Soviets stopped delivering agricultural products from their zone in eastern Germany, in 1946. The American commander, General Lucius Clay, retaliated by stopping shipments of dismantled industries from western Germany into the Soviet Union. The Soviets responded with obstructionist policies, doing everything it could to throw sand in the gears of all four occupied zones.

US and UK zones of occupation combined into a single “bizone” in January 1947, joining with that of France and becoming the “trizone” on June 1, 1948. Representatives of these governments and that of the Benelux nations of Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg met twice in London to discuss the future of Germany, while Soviet leaders threatened to ignore any decisions coming out of such conferences.

The four-power solution was unworkable throughout the postwar period. For the city of Berlin, 1948 would reach the point of crisis.

That March, Soviet authorities slowed cargo to a crawl, individually searching every truck and train. General Clay ordered a halt to train traffic on April 2, ordering that supplies to the military garrison in Berlin be transported by air. Soviets eased their restrictions a week later, but still interrupted road and rail traffic. Meanwhile, Soviet military aircraft began to harass and “buzz” allied flights in and out of West Berlin. On April 5, a Soviet Air Force Yakovlev Yak-3 fighter collided with a British European Airways Vickers Viking 1B airliner near RAF Gatow airfield. Everyone onboard both aircraft, were killed.

The final straw came with the currency crisis of early 1948, when the Deutsche Mark was introduced. The former Reichsmark was severely devalued by this time, with calamitous economic repercussions. The new currency went into use in all four sectors of occupied Berlin, against the wishes of the Soviets. This new currency combined with the Marshall Pan had the potential to revitalize the German economy, and that wouldn’t do. Not for Soviet policy makers, for whom a prostrate German economy remained the objective.

Soviet guards halted all traffic on the autobahn to Berlin on June 19, the day after the new currency was introduced.

At the time, West Berlin had 36 days’ food supplies, and 45 days’ supply of coal. The western nations had scaled military operations down in the wake of the war, to the point where the western sectors of the city had only 8,973 Americans, 7,606 British and 6,100 French. Soviet military forces numbered some 1.5 million. Believing that Allied powers had no choice but to cave to their demands, Soviet authorities cut off the electricity.

While ground routes were never negotiated in and out of occupied Berlin, the same was not true of the air. Three air routes had been agreed upon back in 1945. These went into use on this day in 1948, beginning the largest humanitarian airlift, in history.

Of all the malignant governing ideologies of history, Josef Stalin’s Soviet Union has to be counted among the worst. These people had no qualms about using genocide by starvation as a political tool. They had proven as much during the Holodomor of 1932 – ’33, during which this evil empire had murdered millions of its own citizens, by deliberate starvation. Two million German civilians would be nothing more than a means to an end.

With that many lives at stake, allied authorities calculated that a daily ration of only 1,990 kilocalories would require 646 tons of flour and wheat, 125 tons of cereal, 64 tons of fat, 109 tons of meat and fish, 180 tons of dehydrated potatoes, 180 tons of sugar, 11 tons of coffee, 19 tons of powdered milk, 5 tons of whole milk for children, 3 tons of fresh yeast for baking, 144 tons of dehydrated vegetables, 38 tons of salt and 10 tons of cheese.

Every. Single. Day.

Heat and power for such a population would require 3,475 tons of coal, diesel and gasoline, every day.

United States Air force General Curtis LeMay was asked “Can you haul coal?” LeMay replied “We can haul anything.”

The obstacles were daunting. Postwar demobilization had diminished US cargo capabilities in Europe to a nominal 96 aircraft, theoretically capable of transporting 300 tons per day. Great Britain’s RAF was somewhat better with a capacity of 400 tons, according to General Sir Brian Robertson.

700 tons were nowhere near the 5,000 per day that was needed, but it was a start. With additional aircraft mobilizing all over the United States, the United Kingdom and France, the people of occupied Berlin had to buy into the program.

General Clay went to Ernst Reuter, Berlin’s mayor-elect. “Look, I am ready to try an airlift. I can’t guarantee it will work. I am sure that even at its best, people are going to be cold and people are going to be hungry. And if the people of Berlin won’t stand that, it will fail. And I don’t want to go into this unless I have your assurance that the people will be heavily in approval.”

Luckily, General Albert Wedemeyer was in Europe on an inspection tour, when the crisis broke out. Wedemeyer had been in charge of the previously-largest airlift in history, the China-Burma-India theater route over the Himalayas, known as “The Hump”. Reuter was skeptical but assured the authorities that the people of Berlin were behind the plan. Wedemeyer’s endorsement gave the plan a major boost. The Berlin Airlift began seventy years ago today, June 26, 1948.

The Australian Air force joined in the largest humanitarian effort in history that September. The Canadians never did, believing the operation to be a provocation which would lead to war with the Soviet Union.

Through the Fall and Winter of 1948 – ’49 the airlift carried on. Soviet authorities maintained their stranglehold but, preoccupied with rebuilding their own war-ravaged economy and fearful of the United States’ nuclear capabilities, Stalin had little choice but to look on. On April 15, 1949, the Soviet news agency TASS announced that the Soviets were willing to lift the blockade.

Negotiations were begun almost at once but now, the Allies held the stronger hand. An agreement was announced on May 4 that the blockade would be ended, in eight days’ time. A British convoy drove through the gates at a minute after midnight on May 12, though the airlift would continue, to build up a comfortable surplus.

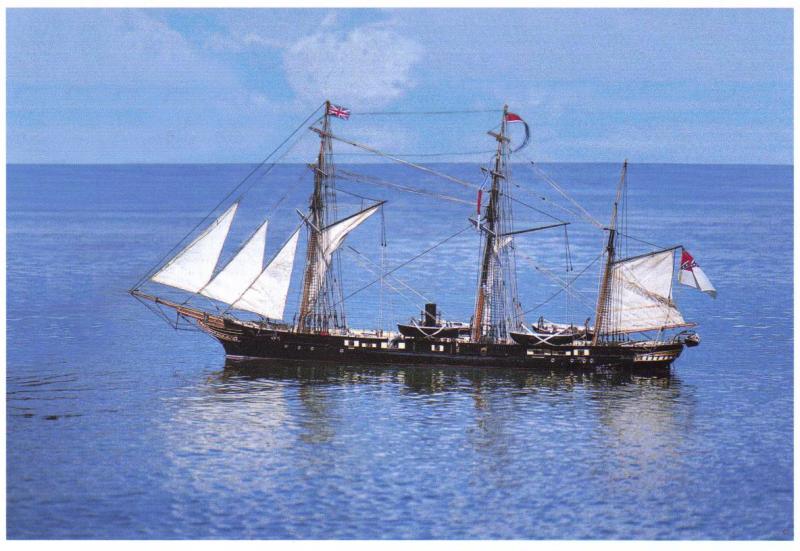

At the height of the operation, an aircraft landed every thirty seconds in West Berlin. The USAF delivered 1,783,573 tons altogether and the RAF 541,937, on a total of 278,228 flights. The Royal Australian Air Force delivered 7,968 tons of freight in over 2,000 sorties. Added together, the Berlin Airlift covered nearly the distance from the Earth, to the Sun.

39 British and 31 American airmen lost their lives during the operation.

In 1961, Communist leaders would erect a wall around their sector of the city. Not to keep foreigners out, but to keep their own unfortunate citizens, in. The Berlin Wall would not come down, for twenty-eight years.

If you enjoyed this “Today in History”, please feel free to re-blog, “like” & share on social media, so that others may find and enjoy it as well. Please click the “follow” button on the right, to receive email updates on new articles. Thank you for your interest, in the history we all share.

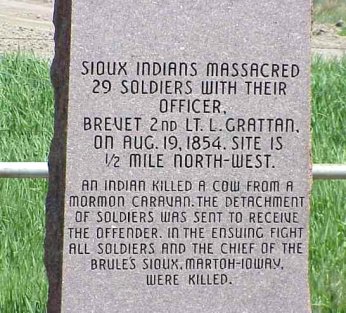

Chief Conquering Bear attempted to negotiate recompense, offering a horse or cow from the tribe’s herd. The owner refused, demanding $25. That same treaty of 1851 specified that such matters would be handled by the local Indian agent, in this case John Whitfield, scheduled to arrive within days with tribal annuities more than sufficient to settle the matter to everyone’s satisfaction.

Chief Conquering Bear attempted to negotiate recompense, offering a horse or cow from the tribe’s herd. The owner refused, demanding $25. That same treaty of 1851 specified that such matters would be handled by the local Indian agent, in this case John Whitfield, scheduled to arrive within days with tribal annuities more than sufficient to settle the matter to everyone’s satisfaction.

The tale of those other two columns is worth a “Today in History” essay of their own if not an entire book, but this is a story about Little Big Horn. Suffice it to say that Major Marcus Reno‘s experience of this day was as grizzly and as shocking, as that moment when the brains and face of his Arikara scout Bloody Knife spattered across his own. Reno’s detachment had entered a buzz saw and would have been annihilated altogether, had it not met up with that of captain Frederick Benteen.

The tale of those other two columns is worth a “Today in History” essay of their own if not an entire book, but this is a story about Little Big Horn. Suffice it to say that Major Marcus Reno‘s experience of this day was as grizzly and as shocking, as that moment when the brains and face of his Arikara scout Bloody Knife spattered across his own. Reno’s detachment had entered a buzz saw and would have been annihilated altogether, had it not met up with that of captain Frederick Benteen.

There is an oft-repeated but mistaken notion that the circus goes back to Roman antiquity. The panem et circenses, (bread and circuses)” of Juvenal, ca AD100, refers more to the ancient precursor of the racetrack, than to anything resembling a modern circus. The only common denominator is the word itself, the Latin root ‘circus’, translating into English, as “circle”.

There is an oft-repeated but mistaken notion that the circus goes back to Roman antiquity. The panem et circenses, (bread and circuses)” of Juvenal, ca AD100, refers more to the ancient precursor of the racetrack, than to anything resembling a modern circus. The only common denominator is the word itself, the Latin root ‘circus’, translating into English, as “circle”. These afternoon shows gained overwhelming popularity by 1770, and Astley hired acrobats, rope-dancers, and jugglers to fill the spaces between equestrian events. The modern circus, was born.

These afternoon shows gained overwhelming popularity by 1770, and Astley hired acrobats, rope-dancers, and jugglers to fill the spaces between equestrian events. The modern circus, was born.

and fear, his demonstrations emphasizing the animal’s intelligence and tractability over ferocity.

and fear, his demonstrations emphasizing the animal’s intelligence and tractability over ferocity.

Humphreys then used a hailing trumpet and ordered the American ship to comply, to which Barron responded “I don’t hear what you say”. Humphreys fired two rounds across Chesapeake’s bow, followed immediately by four broadsides.

Humphreys then used a hailing trumpet and ordered the American ship to comply, to which Barron responded “I don’t hear what you say”. Humphreys fired two rounds across Chesapeake’s bow, followed immediately by four broadsides.

United States Naval Captain James Lawrence was eager to comply, confident in the wake of a number of American victories in single-ship actions.

United States Naval Captain James Lawrence was eager to comply, confident in the wake of a number of American victories in single-ship actions.

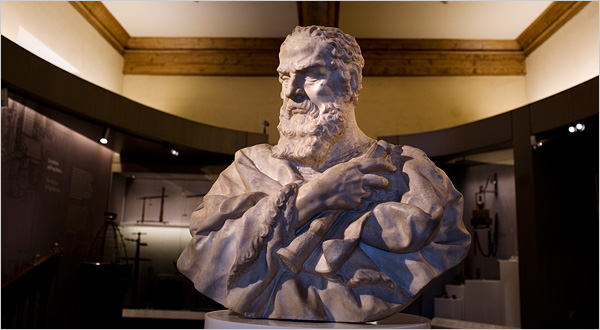

Some 100 years later, two fingers and a tooth were purchased at auction, and have since rejoined their fellow digit at the Museo Galileo. To this day, these remain the only human body parts, in a museum otherwise devoted to scientific instrumentation.

Some 100 years later, two fingers and a tooth were purchased at auction, and have since rejoined their fellow digit at the Museo Galileo. To this day, these remain the only human body parts, in a museum otherwise devoted to scientific instrumentation.

Finally, a constellation of thirteen stars breaks out of the clouds above, signifying a new people, now ready to take its place among the sovereign nations of earth.

Finally, a constellation of thirteen stars breaks out of the clouds above, signifying a new people, now ready to take its place among the sovereign nations of earth.

The militant atheist type wishing to divest himself of all that “church & state” stuff may, at his convenience, feel free to send those dollar bills, to me. I’m in the book.

The militant atheist type wishing to divest himself of all that “church & state” stuff may, at his convenience, feel free to send those dollar bills, to me. I’m in the book.

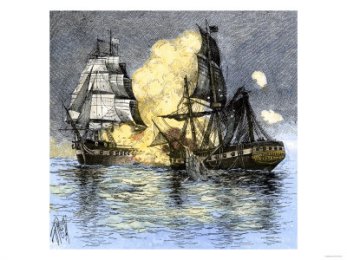

CSS Alabama steamed out of Cherbourg harbor on the morning of June 19, 1864, escorted by the French ironclad Couronne, which remained nearby to ensure that the combat remained in international waters. Kearsarge steamed further to sea as the Confederate vessel approached. There would be no one returning to port until the issue was decided.

CSS Alabama steamed out of Cherbourg harbor on the morning of June 19, 1864, escorted by the French ironclad Couronne, which remained nearby to ensure that the combat remained in international waters. Kearsarge steamed further to sea as the Confederate vessel approached. There would be no one returning to port until the issue was decided. Captain Winslow put his ship around and headed for his adversary at 10:50am. Alabama fired first from a distance of a mile, and continued to fire as the range decreased.

Captain Winslow put his ship around and headed for his adversary at 10:50am. Alabama fired first from a distance of a mile, and continued to fire as the range decreased.

Austrian military history professor Erik Durschmied wrote in his excellent book`

Austrian military history professor Erik Durschmied wrote in his excellent book`

Stoker wrote in his notes, “in Wallachian language means DEVIL”. In a time and place remembered for near-cartoonish levels of violence, Vlad Țepeș stands out for his extraordinary cruelty. There are tales of Țepeș disemboweling his own mistress. That he collected the noses of vanquished adversaries. Some 24,000 of them. That he dined among forests of victims, spitted on poles. That he even impaled the donkeys they rode in on.

Stoker wrote in his notes, “in Wallachian language means DEVIL”. In a time and place remembered for near-cartoonish levels of violence, Vlad Țepeș stands out for his extraordinary cruelty. There are tales of Țepeș disemboweling his own mistress. That he collected the noses of vanquished adversaries. Some 24,000 of them. That he dined among forests of victims, spitted on poles. That he even impaled the donkeys they rode in on.

Outnumbered five-to-one, Ţepeş employed a scorched earth policy, poisoning the waters, diverting small rivers to create marshes and digging traps covered with timber and leaves. He would send sick people among the Turks, suffering lethal diseases such as leprosy, tuberculosis and bubonic plague.

Outnumbered five-to-one, Ţepeş employed a scorched earth policy, poisoning the waters, diverting small rivers to create marshes and digging traps covered with timber and leaves. He would send sick people among the Turks, suffering lethal diseases such as leprosy, tuberculosis and bubonic plague.

The British line advanced up Breed’s Hill twice that afternoon, Patriot fire decimating their number and driving the survivors back down the hill to reform and try again.

The British line advanced up Breed’s Hill twice that afternoon, Patriot fire decimating their number and driving the survivors back down the hill to reform and try again.

You must be logged in to post a comment.