In the early days of the Civil War, the government in Washington refused to recognize the Confederate states’ government, believing any such recognition would amount to legitimizing an illegal entity. The Union refused formal agreement regarding the exchange of prisoners. Following the capture of over a thousand federal troops at the first battle of Bull Run (Manassas), a joint resolution in Congress called for President Lincoln to establish a prisoner exchange agreement.

In July 1862, Union Major General John A. Dix and Confederate Major General D. H. Hill met under flag of truce to draw up an exchange formula, regarding the return of prisoners. The “Dix-Hill Cartel” determined that Confederate and Union Army soldiers were exchanged at a prescribed rate: captives of equivalent ranks were exchanged as equals. Corporals and Sergeants were worth two privates. Lieutenants were four and Colonels fifteen, all the way up to Commanding General, equivalent to sixty private soldiers. Similar exchange rates were established for Naval personnel.

My twice-great grandfather, Corporal Jacob Deppen of the 128th Pennsylvania Infantry, was paroled in such an exchange.

President Lincoln’s emancipation proclamation of September 1862 not only freed those enslaved in Confederate territories, but also provided for the enlistment of black soldiers. The government in Richmond responded that such would be regarded as runaway slaves and not soldiers. Their white officers would be treated as criminals, for inciting servile insurrection.

The policy was made clear in July 1863, following the Union defeat at Fort Wagner, an action depicted in the 1989 film, Glory. The Dix-Hill protocol was formally abandoned on July 30. Neither side was ready for the tide of humanity, about to come.

The US Army began construction the following month on the Rock Island Prison, built on an Island between Davenport Iowa and Rock Island, Illinois. In time, Rock Island would become one of the most infamous POW camps of the north, housing some 12,000 Confederate prisoners, seventeen per cent of whom, died in captivity.

On this day in 1864, the first prisoners had barely moved into the most notorious POW camp of the Civil War, the first Federal soldiers arriving on February 28.

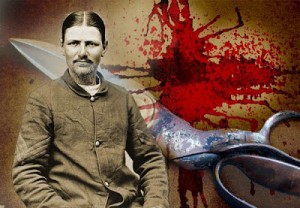

The pictures at the top of this page were taken at Camp Sumter, better known as Andersonville. Conditions in this place defy description. Sergeant Major Robert H. Kellogg of the 16th Regiment Connecticut Volunteers, entered this hell hole on May 2:

“As we entered the place, a spectacle met our eyes that almost froze our blood with horror, and made our hearts fail within us. Before us were forms that had once been active and erect;—stalwart men, now nothing but mere walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin. Many of our men, in the heat and intensity of their feeling, exclaimed with earnestness. “Can this be hell?” “God protect us!” and all thought that he alone could bring them out alive from so terrible a place. In the center of the whole was a swamp, occupying about three or four acres of the narrowed limits, and a part of this marshy place had been used by the prisoners as a sink, and excrement covered the ground, the scent arising from which was suffocating. The ground allotted to our ninety was near the edge of this plague-spot, and how we were to live through the warm summer weather in the midst of such fearful surroundings, was more than we cared to think of just then”.

Over 45,000 Union troops would pass through the verminous open sewer known as Andersonville. Nearly 13,000 died there.

Now all but forgotten, the ‘Eighty acres of Hell’ located in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago was home to some forty thousand Confederate POWs between 1862 and 1865, seventeen per cent of whom, never left. No southern soldier was equipped for the winters at Camp Douglas, nor the filth, or the disease. Nearby Oak Woods Cemetery is home to the largest mass grave, in the western hemisphere.

Union and Confederate governments established 150 such camps between 1861 and 1865, makeshift installations of rickety wooden buildings and primitive sewage systems, often little more than tent cities. Some 347,000 human beings languished in these places, victims of catastrophically poor hygiene, harsh summary justice, starvation, disease and swarming vermin.

The training depot designated camp Rathbun near Elmira New York became the most notorious camp in the north, in 1864. 12,213 Confederate prisoners were held there, often three men to a tent. Nearly 25% of them died there, only slightly less, than Andersonville. The death rate in “Hellmira” was double that of any other camp in the north.

Historians debate the degree to which such brutality resulted from deliberate mistreatment, or economic necessity.

The Union had more experience being a “country” at this time, with well established banking systems and means of commerce and transportation. For the south, the war was an economic catastrophe. The Union blockade starved southern ports of even the basic necessities from the beginning, while farmers abandoned fields to take up arms. Most of the fighting of the Civil War took place on southern soil, destroying incalculable acres of rich farm lands.

The capital at Richmond saw bread riots as early as 1862. Southern Armies subsisted on corn meal and peanuts. The Confederate government responded by printing currency, about a billion dollars worth. By 1864, a Confederate dollar was worth 5¢ in gold. Southern inflation exceeded 9000%, by 1865.

Captain Henry Wirz, commandant of the stockade at Camp Sumter, was tried and executed after the war, only one of two men to be hanged for war crimes. Captain Wirz appeared at trial reclined on a couch, advanced gangrene preventing him from sitting up. To some, the man was a scapegoat. A victim of circumstances beyond his control. To others he is a demon, personally responsible for the hell of Andersonville prison. I make no pretense of answering such a question. The subject is capable of inciting white-hot passion, from that day to this.

On a personal note:

There are many good reasons to study history, among which is an understanding of where we come from. How do we know where we’re going, if we don’t understand where we’ve been.

Should our ancestors be towering historical figures or merely those who played a part, the principle applies on the micro, as well as a larger scale.

Among those farmers who laid down their tools were the four Tyner brothers of North Carolina: James, William, Nicholas and Benjamin. My twice-great Grandfather, Private James Tyner, 52nd North Carolina Infantry, was captured at Spotsylvania Courthouse and imprisoned at “Hellmira”. He died in captivity on March 13, 1865, less than a month before General Lee surrendered at Appomattox. Nicholas alone survived the war, to return to the Sand Hills of North Carolina.

Corporal Jacob Deppen of the 128th PA Infantry re-enlisted with the Army of the James, after his parole. He and Nicholas Tyner would lay down their weapons at Appomattox, former enemies turned countrymen, if they could only figure out how to do it.

William Christian Long was Blacksmith to the 17th Pennsylvania Cavalry, and survived the war. His name may be found on the Pennsylvania monument, at Gettysburg.

Archibald Blue of Drowning Creek North Carolina wanted no part of what he saw as a “rich man’s war” and ordered his five sons away. He was murdered for his politics in 1865. The killer was never found.

Four men, each of whom played a part in the most destructive war, in American history. Without any of these four, I wouldn’t be here to tell their story.

Rick Long

The American Revolution was on its last legs in December 1776. The year had started out well for the Patriot cause but turned into a string of disasters, beginning in August. Food, ammunition and equipment were in short supply by December. Men were deserting as the string of defeats brought morale to a new low. Most of those who remained, ended enlistments at the end of the year.

The American Revolution was on its last legs in December 1776. The year had started out well for the Patriot cause but turned into a string of disasters, beginning in August. Food, ammunition and equipment were in short supply by December. Men were deserting as the string of defeats brought morale to a new low. Most of those who remained, ended enlistments at the end of the year.

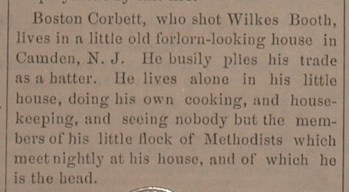

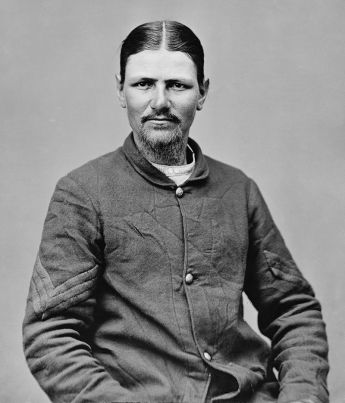

In the first months of the Civil War, Boston Corbett enlisted as a private in the 12th Regiment of the New York state militia. Eccentric behavior quickly got him into trouble. He would carry a bible with him at all times, reading passages aloud and holding unauthorized prayer meetings. He would argue with superior officers, once reprimanding Colonel Daniel Butterfield for using profane language and using the Lord’s name, in vain. That got him a stay in the guardhouse, where he continued to argue.

In the first months of the Civil War, Boston Corbett enlisted as a private in the 12th Regiment of the New York state militia. Eccentric behavior quickly got him into trouble. He would carry a bible with him at all times, reading passages aloud and holding unauthorized prayer meetings. He would argue with superior officers, once reprimanding Colonel Daniel Butterfield for using profane language and using the Lord’s name, in vain. That got him a stay in the guardhouse, where he continued to argue. On June 24, 1864, fifteen members of Corbett’s company were hemmed in and captured, by Confederate Colonel John Singleton Mosby’s men in Culpeper Virginia.

On June 24, 1864, fifteen members of Corbett’s company were hemmed in and captured, by Confederate Colonel John Singleton Mosby’s men in Culpeper Virginia.

Emil Joseph Kapaun was the son of Czech immigrants, a farm kid who grew up in 1920s Kansas. Graduating from Pilsen High, class of 1930, he spent much of the 30s in theological seminary, becoming an ordained priest of the Roman Catholic faith on June 9, 1940.

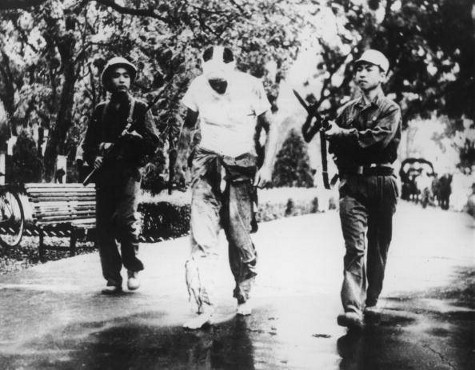

Emil Joseph Kapaun was the son of Czech immigrants, a farm kid who grew up in 1920s Kansas. Graduating from Pilsen High, class of 1930, he spent much of the 30s in theological seminary, becoming an ordained priest of the Roman Catholic faith on June 9, 1940. A single regiment was attacked by the 39th Chinese Corps on November 1, and completely overrun the following day. For the 8th Cav., the battle of Unsan was one of the most devastating defeats of the Korean War. Father Kapaun was ordered to evade, an order he defied. He was performing last rites for a dying soldier, when he was seized by Chinese communist forces.

A single regiment was attacked by the 39th Chinese Corps on November 1, and completely overrun the following day. For the 8th Cav., the battle of Unsan was one of the most devastating defeats of the Korean War. Father Kapaun was ordered to evade, an order he defied. He was performing last rites for a dying soldier, when he was seized by Chinese communist forces. Chinese Communist guards would taunt him during daily indoctrination sessions, “Where is your god now?” Before and after these sessions, he would move through the camp, ministering to Catholic and non-Catholic alike. Kapaun would slip in behind every work detail, cleaning latrines while other prisoners argued over who’d get the job. He’d wash the filthy laundry of those made weak and incontinent with dysentery.

Chinese Communist guards would taunt him during daily indoctrination sessions, “Where is your god now?” Before and after these sessions, he would move through the camp, ministering to Catholic and non-Catholic alike. Kapaun would slip in behind every work detail, cleaning latrines while other prisoners argued over who’d get the job. He’d wash the filthy laundry of those made weak and incontinent with dysentery. In the end, he was too weak to lift the plate that held the meager meal the guards left for him. US Army records report that he died of pneumonia on May 6, 1951, but his fellow prisoners will tell you that he died on May 23, of malnutrition and starvation. He was 35.

In the end, he was too weak to lift the plate that held the meager meal the guards left for him. US Army records report that he died of pneumonia on May 6, 1951, but his fellow prisoners will tell you that he died on May 23, of malnutrition and starvation. He was 35.

Humbert Roque Versace was born in Honolulu on July 2, 1937, the oldest of five sons born to Colonel Humbert Joseph Versace. Writer Marie Teresa “Tere” Rios was his mother, author of the

Humbert Roque Versace was born in Honolulu on July 2, 1937, the oldest of five sons born to Colonel Humbert Joseph Versace. Writer Marie Teresa “Tere” Rios was his mother, author of the  He did his tour, and voluntarily signed up for another six months. By the end of October 1963, Rocky had fewer than two weeks to the end of his service. He had served a year and one-half in the Republic of Vietnam. Now he planned to go to seminary school. He had already received his acceptance letter, from the Maryknoll order.

He did his tour, and voluntarily signed up for another six months. By the end of October 1963, Rocky had fewer than two weeks to the end of his service. He had served a year and one-half in the Republic of Vietnam. Now he planned to go to seminary school. He had already received his acceptance letter, from the Maryknoll order.

The effect was entirely unacceptable to his Communist tormentors. To the people of these villages, this man made sense.

The effect was entirely unacceptable to his Communist tormentors. To the people of these villages, this man made sense.

You must be logged in to post a comment.