In the early days of the Civil War, the government in Washington refused to recognize the Confederate states’ government, believing any such recognition would amount to legitimizing an illegal entity. The Union refused formal agreement regarding the exchange of prisoners. Following the capture of over a thousand federal troops at the first battle of Bull Run (Manassas), a joint resolution in Congress called for President Lincoln to establish a prisoner exchange agreement.

In July 1862, Union Major General John A. Dix and Confederate Major General D. H. Hill met under flag of truce to draw up an exchange formula, regarding the return of prisoners. The “Dix-Hill Cartel” determined that Confederate and Union Army soldiers were exchanged at a prescribed rate: captives of equivalent ranks were exchanged as equals. Corporals and Sergeants were worth two privates. Lieutenants were four and Colonels fifteen, all the way up to Commanding General, equivalent to sixty private soldiers. Similar exchange rates were established for Naval personnel.

My twice-great grandfather, Corporal Jacob Deppen of the 128th Pennsylvania Infantry, was paroled in such an exchange.

President Lincoln’s emancipation proclamation of September 1862 not only freed those enslaved in Confederate territories, but also provided for the enlistment of black soldiers. The government in Richmond responded that such would be regarded as runaway slaves and not soldiers. Their white officers would be treated as criminals, for inciting servile insurrection.

The policy was made clear in July 1863, following the Union defeat at Fort Wagner, an action depicted in the 1989 film, Glory. The Dix-Hill protocol was formally abandoned on July 30. Neither side was ready for the tide of humanity, about to come.

The US Army began construction the following month on the Rock Island Prison, built on an Island between Davenport Iowa and Rock Island, Illinois. In time, Rock Island would become one of the most infamous POW camps of the north, housing some 12,000 Confederate prisoners, seventeen per cent of whom, died in captivity.

On this day in 1864, the first prisoners had barely moved into the most notorious POW camp of the Civil War, the first Federal soldiers arriving on February 28.

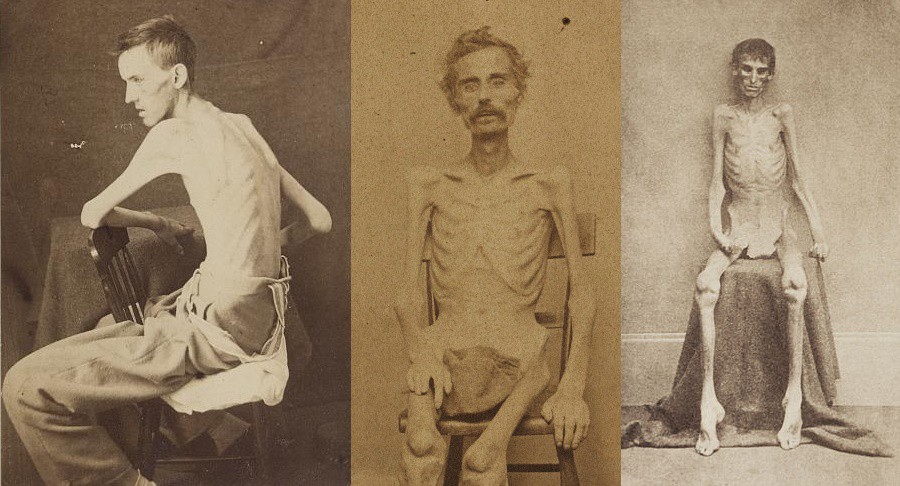

The pictures at the top of this page were taken at Camp Sumter, better known as Andersonville. Conditions in this place defy description. Sergeant Major Robert H. Kellogg of the 16th Regiment Connecticut Volunteers, entered this hell hole on May 2:

“As we entered the place, a spectacle met our eyes that almost froze our blood with horror, and made our hearts fail within us. Before us were forms that had once been active and erect;—stalwart men, now nothing but mere walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin. Many of our men, in the heat and intensity of their feeling, exclaimed with earnestness. “Can this be hell?” “God protect us!” and all thought that he alone could bring them out alive from so terrible a place. In the center of the whole was a swamp, occupying about three or four acres of the narrowed limits, and a part of this marshy place had been used by the prisoners as a sink, and excrement covered the ground, the scent arising from which was suffocating. The ground allotted to our ninety was near the edge of this plague-spot, and how we were to live through the warm summer weather in the midst of such fearful surroundings, was more than we cared to think of just then”.

Over 45,000 Union troops would pass through the verminous open sewer known as Andersonville. Nearly 13,000 died there.

Now all but forgotten, the ‘Eighty acres of Hell’ located in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago was home to some forty thousand Confederate POWs between 1862 and 1865, seventeen per cent of whom, never left. No southern soldier was equipped for the winters at Camp Douglas, nor the filth, or the disease. Nearby Oak Woods Cemetery is home to the largest mass grave, in the western hemisphere.

Union and Confederate governments established 150 such camps between 1861 and 1865, makeshift installations of rickety wooden buildings and primitive sewage systems, often little more than tent cities. Some 347,000 human beings languished in these places, victims of catastrophically poor hygiene, harsh summary justice, starvation, disease and swarming vermin.

The training depot designated camp Rathbun near Elmira New York became the most notorious camp in the north, in 1864. 12,213 Confederate prisoners were held there, often three men to a tent. Nearly 25% of them died there, only slightly less, than Andersonville. The death rate in “Hellmira” was double that of any other camp in the north.

Historians debate the degree to which such brutality resulted from deliberate mistreatment, or economic necessity.

The Union had more experience being a “country” at this time, with well established banking systems and means of commerce and transportation. For the south, the war was an economic catastrophe. The Union blockade starved southern ports of even the basic necessities from the beginning, while farmers abandoned fields to take up arms. Most of the fighting of the Civil War took place on southern soil, destroying incalculable acres of rich farm lands.

The capital at Richmond saw bread riots as early as 1862. Southern Armies subsisted on corn meal and peanuts. The Confederate government responded by printing currency, about a billion dollars worth. By 1864, a Confederate dollar was worth 5¢ in gold. Southern inflation exceeded 9000%, by 1865.

Captain Henry Wirz, commandant of the stockade at Camp Sumter, was tried and executed after the war, only one of two men to be hanged for war crimes. Captain Wirz appeared at trial reclined on a couch, advanced gangrene preventing him from sitting up. To some, the man was a scapegoat. A victim of circumstances beyond his control. To others he is a demon, personally responsible for the hell of Andersonville prison. I make no pretense of answering such a question. The subject is capable of inciting white-hot passion, from that day to this.

On a personal note:

There are many good reasons to study history, among which is an understanding of where we come from. How do we know where we’re going, if we don’t understand where we’ve been.

Should our ancestors be towering historical figures or merely those who played a part, the principle applies on the micro, as well as a larger scale.

Among those farmers who laid down their tools were the four Tyner brothers of North Carolina: James, William, Nicholas and Benjamin. My twice-great Grandfather, Private James Tyner, 52nd North Carolina Infantry, was captured at Spotsylvania Courthouse and imprisoned at “Hellmira”. He died in captivity on March 13, 1865, less than a month before General Lee surrendered at Appomattox. Nicholas alone survived the war, to return to the Sand Hills of North Carolina.

Corporal Jacob Deppen of the 128th PA Infantry re-enlisted with the Army of the James, after his parole. He and Nicholas Tyner would lay down their weapons at Appomattox, former enemies turned countrymen, if they could only figure out how to do it.

William Christian Long was Blacksmith to the 17th Pennsylvania Cavalry, and survived the war. His name may be found on the Pennsylvania monument, at Gettysburg.

Archibald Blue of Drowning Creek North Carolina wanted no part of what he saw as a “rich man’s war” and ordered his five sons away. He was murdered for his politics in 1865. The killer was never found.

Four men, each of whom played a part in the most destructive war, in American history. Without any of these four, I wouldn’t be here to tell their story.

Rick Long

One lesson in all this is how recent it was, and how far we’ve progressed in minimizing aggression–at least within national borders. Other countries, back to Babylon and Egypt, then later Brazil had slavery, but not combined with a tariff nullification Cold War that went hot.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It sounds as bad as the the POWs camps of Japan and Germans during the Second World War. An appealing way to treat a human being.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For many years, the number of dead from the American Civil War was understood to be 632,000. Recent computerized tallies compared before and after census numbers, and controlled for immigration. These revealed numbers closer to 650-850 thousand, and settled on a mid-point of 750,000. More dead than every war this nation has ever fought, from the Revolution to the wars on terror. Combined.

LikeLiked by 1 person

They are staggering figures and presumably not as well documented or appreciated Stateside as the First and Second World Wars?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Does that number inculde civilian deaths in the South? And deaths during reconstruction? Which weren t small numbers

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t think the number included reconstruction, just the war. Everything I’ve read indicates far higher casualties in the south, despite a manpower size disadvantage of 2-to-1. Is that your understanding?

LikeLike

My understanding is no one knows. In part because records sucked, in part because no one could figure out stuff like Southern non combatants dying from various things. Hunger and homelessness leading to all sorts of health issues

Been working on trying to figure out the war debt issue myself and how long it took to pay off. I know the South had to cover our debt on our own, plus part of the damnyankees debt, all while our economy was destroyed.

Again can’t find any good answers on that either

LikeLiked by 1 person

Plus a lot of my links have disappeared over the years making it more difficult to track down info that portrays lincoln and those people in a negative light.

Was trying to do a post on how anti Washington, Jefferson etc all and anti constitution the tyrant was before he gained office but none of those articles are available on the NC State webpage any longer

Clearly shot callers are purging info and still rewriting history to suit their needs

LikeLiked by 1 person

Are you in NC? That’s where my father’s people come from.

LikeLike

Yup

Right outside Mayberry by the sea

LikeLiked by 1 person

😂 We’re out in Richmond & Scotland counties, in the sand hills.

LikeLike

I know bith very well

Spent years at Ft Bragg. My people hail from Vrigina mostly. I stayed here after the military. No real opportunities in Appalachia anymore

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re a former Army Ranger if I’m not mistaken. I figured you’d know Ft Bragg.

LikeLike

Started off in 1st Ranger Batt and worked my way up but the early days as a Ranger are my most fond military memories

The games are fun. I am a huge fan of the various strength sports. The Girls enjoy all the dancing and what not. Wouldn’t want to go more then once a year but it’s fun to do

I like the local festivals. Helps remind me why the 24 years I did weren t a complete waste

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for your service.

LikeLike

LOL I did it all for the nookie 😉

LikeLiked by 2 people

I still go to the high land games out that way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Those things look like a hoot. Never been.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Plausibly Live and commented:

My Great Grandfather, Francis Marion Holt (1st Arkansas Cavalry (US)), was a POW for a short time. Many other of “Arkansas’ damned Yankees” were not as lucky as he was.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My Great Grandfather, Francis Marion Holt (1st Arkansas Cavalry (US)), was a POW for a short time. Many other of “Arkansas’ damned Yankees” were not as lucky as he was…

LikeLiked by 1 person

This one hits home with a lot of us, I think.

LikeLiked by 1 person