In the Elizabethan and Stuart ages, exploration and colonization was a private enterprise. The English Crown would grant exclusive rights to individuals and corporations to form and exploit colonies, in exchange for sovereignty and a portion of the proceeds. Such propositions were high risk/reward, profit-driven enterprises, of interest to a relative few explorers and investors.

Queen Elizabeth I of England granted Walter Raleigh a charter to establish a colony north of Spanish Florida in 1583, the area called “Virginia” in honor of the virgin Queen. At the time, the name applied to the entire coastal region from South Carolina to Maine and included Bermuda.

Queen Elizabeth I of England granted Walter Raleigh a charter to establish a colony north of Spanish Florida in 1583, the area called “Virginia” in honor of the virgin Queen. At the time, the name applied to the entire coastal region from South Carolina to Maine and included Bermuda.

By the turn of the 17th century, Raleigh’s influence with the Queen was just about nil. Liz’ only interest seemed to be the revenue stream produced for the crown, and Raleigh was providing none after sinking £40,000 into the disastrous “Lost Colony of Roanoke”.

By the mid-1590s, a new colonial plan identified parts of northern Virginia where climate conditions better suited English sensibilities, than those of the more southerly latitudes. The area produced vast wealth from the cold-water fish prized by Europeans, providing the foothold and profits required to support the addition of settlers.

Early explorers to the area included Sir Humphrey Gilbert, Martin Pring and George Weymouth, who brought back an American Native named Squanto, who learned to speak English before returning to his homeland. Sir John Smith called the area “New England”.

Bartholomew Gosnold departed Falmouth, Cornwall in 1602 with 32 onboard the barque “Concord”. Intending to establish a colony in New England, Gosnold sailed due west to the Azores, coming ashore at Cape Elizabeth Maine, on May 14. He sailed into Provincetown Harbor the following day, naming the place “Cape Cod”.

Following the coastline, Gosnold discovered an island covered with wild grapes. Naming it after his deceased daughter, he called the place Martha’s Vineyard. The expedition came ashore on Cuttyhunk in the Elizabethan island chain where they briefly ran a trading post, before heading back to England. Today, Gosnold is the smallest town in Massachusetts with a population of 75 with most of the land owned by the Forbes family.

Following the coastline, Gosnold discovered an island covered with wild grapes. Naming it after his deceased daughter, he called the place Martha’s Vineyard. The expedition came ashore on Cuttyhunk in the Elizabethan island chain where they briefly ran a trading post, before heading back to England. Today, Gosnold is the smallest town in Massachusetts with a population of 75 with most of the land owned by the Forbes family.

The title of “first European” may be a misnomer, as Vikings are believed to have explored the area as early as 1000AD. The land was fruitful for those first Viking explorers, but the indigenous peoples fought back ferociously, causing the Nordic interloper to withdraw to the more easily colonized areas of Greenland and Iceland.

The first Puritans fetched up on the shores of Cape Cod in 1620, staying long enough to draw up the first written governing framework in the colonies, signing the Mayflower Compact off the shore of “P’town” on November 11. Today the sandy soil and scrubby vegetation of the Cape is a delight to tourists, but those first settlers weren’t feeling it. They had to eat. The only positive result from two exploratory trips ashore was the discovery of seed corn stashed by the natives. A third trip ashore resulted in a hostile “first encounter” on the beaches of modern day Eastham, persuading the “Pilgrims” that this wasn’t their kind of place. They left the Cape for good on December 16, dropping anchor at Plymouth Harbor.

The Pilgrims would later encounter the English-speaking natives Samoset and Squanto, who helped to conclude peace terms with Massasoit, Sachem of the Wampanoag.

Some 90% of the native population had been wiped out in the two years preceding, by an epidemic long thought to be smallpox but now believed to be Leptospirosis, a highly contagious pulmonary hemorrhagic syndrome. Things may have otherwise gone for the Pilgrims as they did for those Vikings of 600 years earlier, but that must be a tale for another day.

Militia from my own town of Falmouth and neighboring Sandwich poured onto the beaches on April 3, 1779, opposing a landing by 220 Regulars in the modern day area of Surf Drive. The invaders were repulsed but not before little Falmouth sustained a cannonade of ball shot and grape that lasted from eleven in the morning, until dark.

The British warship HMS Nimrod fired on my little town during the War of 1812. It’s closed now, but the building formerly housing the Nimrod Restaurant, still sports a hole in the wall where the cannon ball came in.

The British warship HMS Nimrod fired on my little town during the War of 1812. It’s closed now, but the building formerly housing the Nimrod Restaurant, still sports a hole in the wall where the cannon ball came in.

Cape Cod was among the first areas settled by the English in North America, the town of Sandwich established in 1637 followed by Barnstable and Yarmouth, in 1639. The thin soil was ill suited to agriculture, and intensive farming techniques eroded topsoil. Farmers grazed cattle on the grassy dunes of the shoreline, only to watch “in horror as the denuded sands ‘walked’ over richer lands, burying cultivated fields and fences.”

By 1800, Cape Cod was all but denuded of trees and firewood had to be transported by boat from Maine. Local agriculture was all but abandoned by 1860, save for better-suited, smaller scale crops such as cranberries and strawberries. By 1950, Cape Cod forests had recovered in a way not seen since the late 1700s.

The early Industrial Revolution that built up Rhode Island and Massachusetts bypassed much of Cape Cod, but not entirely. Blacksmiths Isaac Keith and Ezekiel Ryder began building small buggies and sleighs in the Upper Cape town of Bourne, in 1828. Two years later Keith went off on his own. By the Gold Rush of 1849, the Keith Car Works was a major builder of the Conestoga Wagons found throughout the United States and Canada, as well as its smaller, lighter cousin, the Prairie Schooner. Before the railroads, Conestoga wagons were heavily used in the transportation of shade tobacco grown in Connecticut, western Massachusetts and southern Vermont, even now some of the finest cigar binders and wrappers available. To this day we still call cigars, “stogies”.

The dredging of a canal connecting the Manomet and Scusset rivers and cutting 62 miles off the water route from Boston to New York had been talked about since the time of Miles Standish. Construction of a privately owned toll canal began on June 22, 1909. Giant boulders left by the glaciers and ghastly winter weather hampered construction, the canal finally opening on July 29, 1914 and charging a maximum of $16 per vessel. Navigation was difficult, due to a 5-plus mile-per-hour current combined with a maximum width of 100′ and a max. depth of 25-feet. Several accidents damaged the canal’s reputation and toll revenues failed to meet investors’ expectations.

The dredging of a canal connecting the Manomet and Scusset rivers and cutting 62 miles off the water route from Boston to New York had been talked about since the time of Miles Standish. Construction of a privately owned toll canal began on June 22, 1909. Giant boulders left by the glaciers and ghastly winter weather hampered construction, the canal finally opening on July 29, 1914 and charging a maximum of $16 per vessel. Navigation was difficult, due to a 5-plus mile-per-hour current combined with a maximum width of 100′ and a max. depth of 25-feet. Several accidents damaged the canal’s reputation and toll revenues failed to meet investors’ expectations.

German submarine U-156 surfaced off Nauset beach in Orleans on July 21, 1918, shelling the tug Perth Amboy and its string of towed barges. The federal government took over the canal under a presidential proclamation within four days, later placing it under the jurisdiction of the Army Corps of Engineers. The canal was re-dredged as part of President Roosevelt’s depression era Works Progress Administration to its current width of 480-feet and depth of 32-feet and connected to the mainland by the Sagamore, Bourne, and Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridges.

Despite the WuFlu, millions of tourists will wait countless hours this year in a sea of brake lights, to cross those two narrow roadways onto “the Cape” to enjoy that brief blessed moment of warmth hidden amidst our four seasons, known locally as “almost winter, winter, still winter and bridge construction”.

Despite the WuFlu, millions of tourists will wait countless hours this year in a sea of brake lights, to cross those two narrow roadways onto “the Cape” to enjoy that brief blessed moment of warmth hidden amidst our four seasons, known locally as “almost winter, winter, still winter and bridge construction”.

If anyone wonders why my buddy Carl calls me the “Cape Cod Curmudgeon”, I can only say in my own defense. I’ve been commuting through that crap, for decades.

Childhood memories of standing in line. Smiling. Trusting. And then…the Gun. That sound. Whack! The scream. That feeling of betrayal…being shuffled along. Next!

Childhood memories of standing in line. Smiling. Trusting. And then…the Gun. That sound. Whack! The scream. That feeling of betrayal…being shuffled along. Next!

And did you know? The American Revolution was fought out, entirely in the midst of a smallpox pandemic.

And did you know? The American Revolution was fought out, entirely in the midst of a smallpox pandemic. The idea of inoculation was not new. Terrible outbreaks occurred in Colonial Boston in 1640, 1660, 1677-1680, 1690, 1702, and 1721, killing hundreds, each time. At the time, sickness was considered the act of an angry God. Religious faith frowned on experimentation on the human body.

The idea of inoculation was not new. Terrible outbreaks occurred in Colonial Boston in 1640, 1660, 1677-1680, 1690, 1702, and 1721, killing hundreds, each time. At the time, sickness was considered the act of an angry God. Religious faith frowned on experimentation on the human body. Colonists were chary of the procedure, deeply suspicious of how deliberately infecting a healthy person, could produce a desirable outcome. John Adams submitted to the procedure in 1764 and gave the following account:

Colonists were chary of the procedure, deeply suspicious of how deliberately infecting a healthy person, could produce a desirable outcome. John Adams submitted to the procedure in 1764 and gave the following account: As Supreme Commander, General Washington had a problem. An inoculated soldier would be unfit for weeks before returning to duty. Doing nothing and hoping for the best was to invite catastrophe but so was the inoculation route, as even mildly ill soldiers were contagious and could set off a major outbreak.

As Supreme Commander, General Washington had a problem. An inoculated soldier would be unfit for weeks before returning to duty. Doing nothing and hoping for the best was to invite catastrophe but so was the inoculation route, as even mildly ill soldiers were contagious and could set off a major outbreak.

So it was on December 9, 1979, smallpox was officially described, as eradicated. The only infectious disease ever so declared.

So it was on December 9, 1979, smallpox was officially described, as eradicated. The only infectious disease ever so declared.

A female lion, “Soda”, was purchased sometime later. The lions were destined to spend their adult years in a Paris zoo but both remembered from whence they had come. Both animals recognized William Thaw on a later visit to the zoo, rolling onto their backs in expectation of a good belly rub.

A female lion, “Soda”, was purchased sometime later. The lions were destined to spend their adult years in a Paris zoo but both remembered from whence they had come. Both animals recognized William Thaw on a later visit to the zoo, rolling onto their backs in expectation of a good belly rub. Escadrille N.124 changed its name in December 1916, adopting that of a French hero of the American Revolution. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette.

Escadrille N.124 changed its name in December 1916, adopting that of a French hero of the American Revolution. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette.

Burgoyne’s movements began well with the near-bloodless capture of Fort Ticonderoga in early July, 1777. By the end of July, logistical and supply problems caused Burgoyne’s forces to bog down. On July 27, a Huron-Wendat warrior allied with the British army murdered one Jane McCrae, the fiancé of a loyalist serving in Burgoyne’s army. Gone was the myth of “civilized” British conduct of the war, as dead as the dark days of late 1776 and General Washington’s “Do or Die” crossing of the Delaware and the Christmas attack on Trenton.

Burgoyne’s movements began well with the near-bloodless capture of Fort Ticonderoga in early July, 1777. By the end of July, logistical and supply problems caused Burgoyne’s forces to bog down. On July 27, a Huron-Wendat warrior allied with the British army murdered one Jane McCrae, the fiancé of a loyalist serving in Burgoyne’s army. Gone was the myth of “civilized” British conduct of the war, as dead as the dark days of late 1776 and General Washington’s “Do or Die” crossing of the Delaware and the Christmas attack on Trenton. Meanwhile, attempts to solve the supply problem culminated in the August 16 Battle of Bennington, a virtual buzz saw in which New Hampshire and Massachusetts militiamen under General John Stark along with the Vermont militia of Colonel Seth Warner and Ethan Allen’s “Green Mountain Boys”, killed or captured nearly 1,000 of Burgoyne’s men.

Meanwhile, attempts to solve the supply problem culminated in the August 16 Battle of Bennington, a virtual buzz saw in which New Hampshire and Massachusetts militiamen under General John Stark along with the Vermont militia of Colonel Seth Warner and Ethan Allen’s “Green Mountain Boys”, killed or captured nearly 1,000 of Burgoyne’s men. Meanwhile Howe’s capture of Philadelphia met with only limited success, leading to his resignation as Commander in Chief of the American station and Sir Henry Clinton, withdrawing troops to New York.

Meanwhile Howe’s capture of Philadelphia met with only limited success, leading to his resignation as Commander in Chief of the American station and Sir Henry Clinton, withdrawing troops to New York.

Fort Moultrie surrendered without a fight on May 7. Clinton demanded unconditional surrender the following day but Lincoln bargained for the “Honours of War”. Prominent citizens were by this time, asking Lincoln to surrender. On May 11, the British fired heated shot into the city, burning several homes. Benjamin Lincoln surrendered on May 12.

Fort Moultrie surrendered without a fight on May 7. Clinton demanded unconditional surrender the following day but Lincoln bargained for the “Honours of War”. Prominent citizens were by this time, asking Lincoln to surrender. On May 11, the British fired heated shot into the city, burning several homes. Benjamin Lincoln surrendered on May 12. In the summer of 1780, American General Horatio Gates suffered humiliating defeat at the Battle of Camden. Cornwallis idea of turning over one state after another to loyalists failed to materialize, as the ham-fisted brutality of officers like Banastre Tarleton, incited feelings of resentment among would-be supporters. Like the Roman general Fabius who could not defeat the Carthaginians in pitched battle, General Washington’s brilliant protege Nathaniel Greene pursued a “hit & run” strategy of “scorched earth”, attacking supply trains harassing Cornwallis’ movements at every turn.

In the summer of 1780, American General Horatio Gates suffered humiliating defeat at the Battle of Camden. Cornwallis idea of turning over one state after another to loyalists failed to materialize, as the ham-fisted brutality of officers like Banastre Tarleton, incited feelings of resentment among would-be supporters. Like the Roman general Fabius who could not defeat the Carthaginians in pitched battle, General Washington’s brilliant protege Nathaniel Greene pursued a “hit & run” strategy of “scorched earth”, attacking supply trains harassing Cornwallis’ movements at every turn. Through the Carolinas and on to Virginia, Greene’s forces pursued Cornwallis’ army. With Greene dividing his forces, General Daniel Morgan delivered a crushing defeat, defeating Tarleton’s unit at a place called Cowpens in January, 1781. The battle of Guilford Courthouse was an expensive victory, costing Cornwallis a quarter of his strength and forcing a move to the coast in hopes of resupply.

Through the Carolinas and on to Virginia, Greene’s forces pursued Cornwallis’ army. With Greene dividing his forces, General Daniel Morgan delivered a crushing defeat, defeating Tarleton’s unit at a place called Cowpens in January, 1781. The battle of Guilford Courthouse was an expensive victory, costing Cornwallis a quarter of his strength and forcing a move to the coast in hopes of resupply.

For nine years, threat of war with Mexico stayed the American hand. Through all or part of the next four Presidential terms, formal annexation of the Independent Republic was never far from view. Through all or part of the Jackson, Van Buren and Harrison administrations, it was not until 1944 when President John Tyler restarted negotiations. Issues related to the balance between slave and free states between north and south, doomed the treaty to failure. It was March 1, 1845 when Tyler finally got his joint resolution, with support from President-elect James K. Polk. Texas was admitted to the union on December 29.

For nine years, threat of war with Mexico stayed the American hand. Through all or part of the next four Presidential terms, formal annexation of the Independent Republic was never far from view. Through all or part of the Jackson, Van Buren and Harrison administrations, it was not until 1944 when President John Tyler restarted negotiations. Issues related to the balance between slave and free states between north and south, doomed the treaty to failure. It was March 1, 1845 when Tyler finally got his joint resolution, with support from President-elect James K. Polk. Texas was admitted to the union on December 29. In April 1846, Mexican troops crossed the Rio Grande and invaded Brownsville Texas, attacking US troops 20 miles upriver from Taylor’s camp.

In April 1846, Mexican troops crossed the Rio Grande and invaded Brownsville Texas, attacking US troops 20 miles upriver from Taylor’s camp.

The earliest discernible Mother’s day dates back to 1200-700BC and descending from the Phrygian rituals of modern day Turkey and Armenia. “Cybele” was the great Phrygian goddess of nature, mother of the Gods, of humanity, and of all the beasts of the natural world, her cult spreading throughout Eastern Greece with colonists from Asia Minor.

The earliest discernible Mother’s day dates back to 1200-700BC and descending from the Phrygian rituals of modern day Turkey and Armenia. “Cybele” was the great Phrygian goddess of nature, mother of the Gods, of humanity, and of all the beasts of the natural world, her cult spreading throughout Eastern Greece with colonists from Asia Minor. In the sixteenth century, it became popular for Protestants and Catholics alike to return to their “mother church” whether that be the church of their own baptism, the local parish church, or the nearest cathedral. Anyone who did so was said to have gone “a-mothering”. Domestic servants were given the day off and this “Mothering Sunday”, the 4th Sunday in Lent, was often the only time when whole families could get together. Children would gather wild flowers along the way, to give to their own mothers or to leave in the church. Over time the day became more secular, but the tradition of gift giving continued.

In the sixteenth century, it became popular for Protestants and Catholics alike to return to their “mother church” whether that be the church of their own baptism, the local parish church, or the nearest cathedral. Anyone who did so was said to have gone “a-mothering”. Domestic servants were given the day off and this “Mothering Sunday”, the 4th Sunday in Lent, was often the only time when whole families could get together. Children would gather wild flowers along the way, to give to their own mothers or to leave in the church. Over time the day became more secular, but the tradition of gift giving continued.

Ann Maria Reeves Jarvis was a social activist in mid-19th century western Virginia. Pregnant with her sixth child in 1858, she and other women formed “Mothers’ Day Work Clubs”, to combat the health and sanitary conditions leading at that time to catastrophic levels of infant mortality. Jarvis herself gave birth between eleven and thirteen times in a seventeen year period.

Ann Maria Reeves Jarvis was a social activist in mid-19th century western Virginia. Pregnant with her sixth child in 1858, she and other women formed “Mothers’ Day Work Clubs”, to combat the health and sanitary conditions leading at that time to catastrophic levels of infant mortality. Jarvis herself gave birth between eleven and thirteen times in a seventeen year period. Following Jarvis’ death in 1905, her daughter Anna conceived of Mother’s Day as a way to honor her legacy and to pay respect for the sacrifices made by all mothers, on behalf of their children.

Following Jarvis’ death in 1905, her daughter Anna conceived of Mother’s Day as a way to honor her legacy and to pay respect for the sacrifices made by all mothers, on behalf of their children.

This story is dedicated to two of the most beautiful women in my life. Ginny Long, thanks Mom, for not throttling me all those times you could have. And most especially, for all those times when you SHOULD have. Sheryl Kozens Long, thanks for 25 great years. Rest in peace, sugar. I wish you didn’t have to leave us, quite so soon.

This story is dedicated to two of the most beautiful women in my life. Ginny Long, thanks Mom, for not throttling me all those times you could have. And most especially, for all those times when you SHOULD have. Sheryl Kozens Long, thanks for 25 great years. Rest in peace, sugar. I wish you didn’t have to leave us, quite so soon.

The Plaza Hotel menu was heavy on the French in those days and Ettore began to add some Italian. A little pasta, a nice tomato sauce. Before long, he was promoted to head chef.

The Plaza Hotel menu was heavy on the French in those days and Ettore began to add some Italian. A little pasta, a nice tomato sauce. Before long, he was promoted to head chef. Maurice and Eva Weiner were patrons of the restaurant, and owners of a self-service grocery store chain. The couple helped develop large-scale canning operations. Before long Ettore and Mario bought farm acreage in Milton Pennsylvania, to raise tomatoes. In 1928, they changed the name on the label, making it easier for a tongue-tied non-Italian consumer, to pronounce. Calling himself “Hector” for the same reason, Ettore said “Everyone is proud of his own family name, but sacrifices are necessary for progress.”

Maurice and Eva Weiner were patrons of the restaurant, and owners of a self-service grocery store chain. The couple helped develop large-scale canning operations. Before long Ettore and Mario bought farm acreage in Milton Pennsylvania, to raise tomatoes. In 1928, they changed the name on the label, making it easier for a tongue-tied non-Italian consumer, to pronounce. Calling himself “Hector” for the same reason, Ettore said “Everyone is proud of his own family name, but sacrifices are necessary for progress.” During the Great Depression, Hector would tout the benefits of pasta, praising the stuff as an affordable, hot and nutritious meal for the whole family.

During the Great Depression, Hector would tout the benefits of pasta, praising the stuff as an affordable, hot and nutritious meal for the whole family.

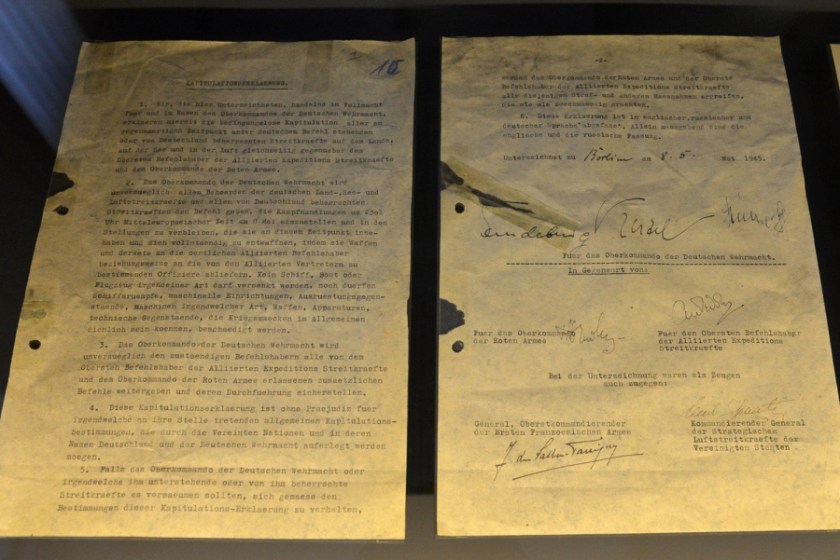

The German government announced the end of hostilities right away to its own people, but most of the Allied governments, remained silent. It was nearly midnight the following day when Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel signed a second instrument of surrender, in the Berlin headquarters of Soviet General Georgy Zhukov.

The German government announced the end of hostilities right away to its own people, but most of the Allied governments, remained silent. It was nearly midnight the following day when Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel signed a second instrument of surrender, in the Berlin headquarters of Soviet General Georgy Zhukov. And still, the world waited.

And still, the world waited. President Truman’s speech begins: “This is a solemn but a glorious hour. I only wish that Franklin D. Roosevelt had lived to witness this day. General Eisenhower informs me that the forces of Germany have surrendered to the United Nations. The flags of freedom fly over all Europe. For this victory, we join in offering our thanks to the Providence which has guided and sustained us through the dark days of adversity”.

President Truman’s speech begins: “This is a solemn but a glorious hour. I only wish that Franklin D. Roosevelt had lived to witness this day. General Eisenhower informs me that the forces of Germany have surrendered to the United Nations. The flags of freedom fly over all Europe. For this victory, we join in offering our thanks to the Providence which has guided and sustained us through the dark days of adversity”. Nearly every extermination camp, death march, ghetto and pogrom now remembered as the Holocaust, occurred on the Eastern Front.

Nearly every extermination camp, death march, ghetto and pogrom now remembered as the Holocaust, occurred on the Eastern Front.

You must be logged in to post a comment.