The Argonne Forest is a long strip of wild woodland and stony mountainside in northeastern France, a hunting preserve since the earliest days of the Bourbon Kings. For most of WWI, the Argonne remained behind German lines. On October 2, 1918, nine companies of the US 77th “Metropolitan Division” came to take part of it back.

Their objective was the Charlevaux ravine and a road & railroad on the other side, cutting off German communications in the sector. As heavy fighting drew to a close on the first day, the men found a way up hill 198 and began to dig in for the night.

Major Charles White Whittlesey, commanding, thought that things were too quiet that first night. Orders called for them to be supported by two American units on their right and a French force on their left/ That night, the voices drifting in from the darkness, were speaking German.

They had come up against a heavily defended double trench line and, unknown at the time, allied forces to their left and right had been cut off and stalled. The Metropolitan Division was alone, and surrounded.

The fighting was near constant on day two, with no chance of getting a runner through. Whittlesey dispatched a message by carrier pigeon, “Many wounded. We cannot evacuate.” The last thing that German forces wanted was for an enemy messenger to get through, and the bird went down in a hail of German bullets.

Whittlesey grabbed another pigeon and wrote “Men are suffering. Can support be sent?”/ That second bird would be shot down as well.

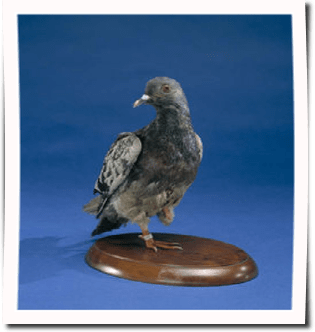

On day three, the “lost battalion” came under fire from its own artillery. Whittlesey grabbed his third and last carrier pigeon, “Cher Ami”, and frantically wrote out his message.

German gunfire exploded from the high ridges above them as this bird, too, fluttered to the ground. Soon she was up again, flying out of sight despite the hail of bullets. She arrived in her coop 65 minutes later, shot through the breast and blind in one eye. The message, hanging by a single tendon from a leg all but shot off, read: “WE ARE ALONG THE ROAD PARALELL 276.4. OUR ARTILLERY IS DROPPING A BARRAGE DIRECTLY ON US. FOR HEAVENS SAKE STOP IT”.

Drops of food and supplies were attempted from the air, but they all ended up in German hands.

By October 7, food and ammunition were running out. 554 had entered the Ardennes five days earlier, now fifty per cent were either dead, or wounded. Water was available from a nearby stream, but only at the cost of exposure to German fire. Bandages had to be removed from the dead in order to treat the wounded. Medicine was completely out and men were falling ill. Even so, survivors continued to fight off German attacks from all sides.

Out of the forest emerged a blindfolded American prisoner, carrying a white flag. He’d been sent with a message, from the German commander:

The suffering of your wounded men can be heard over here in the German lines, and we are appealing to your humane sentiments to stop. A white flag shown by one of your men will tell us that you agree with these conditions. Please treat Private Lowell R. Hollingshead [the bearer] as an honorable man. He is quite a soldier. We envy you. The German commanding officer.

Though he later denied it, Whittlesey’s response was remembered as “You go to hell!”. White sheets placed to help allied aircraft find their position were pulled in, lest they be mistaken for flags of surrender. The meaning was unmistakable. When they were finally relieved the following day, only 194 were fit to walk out on their own.

The Meuse-Argonne offensive of which it was part would last forty seven days, and account for the greatest single-battle loss of life, in American military history.

Edward Leslie Grant attended Dean Academy in his home town of Franklin, Massachusetts, and later graduated from Harvard University. “Harvard” Eddie Grant became a Major League ballplayer, playing utility infielder for the Cleveland Indians as early as 1905.

Grant delighted in aggravating his fellow infielders, calling the ball with the grammatically correct “I have it”, instead of the customary “I got it”.

Grant played for the Philadelphia Phillies and the Cincinnati Reds, before retiring from the New York Giants and opening a Law Office in Boston. He was one of the first men to enlist when the US entered WWI in 1917, becoming a Captain in the 77th Infantry Division, A.E.F.

Sixty former ballplayers were killed during the Great War, including nine former Major League players, twenty-six minor players, three negro leaguers and a number who played college, semi-pro and amateur. Another four played in the Australian League. Harvard Eddie Grant was killed leading a search for the Lost Battalion on October 5, the first Major League ball player to be killed in the Great War.

Eddie Grant was honored on Memorial Day, 1921, as representatives of the US Armed Forces and Major League Baseball joined with his sisters to unveil a plaque in center field at the Polo Grounds. From that day until the park closed in 1957, a wreath was solemnly placed at the foot of that plaque after the first game of every double header. He is memorialized by the Edward L. Grant Highway in The Bronx, and by Grant Field at Dean College in Franklin, Massachusetts.

Major Whittlesey, Captain George McMurtry, and Captain Nelson Holderman all received the Medal of Honor for their actions atop hill 198. Whittlesey was further honored as a pallbearer at the interment ceremony for the Unknown Soldier, but his experience weighed heavily on him.

In what is believed to have been a suicide, Charles White Whittlesey disappeared from the SS Toloa bound for Havana in 1921, leaving instructions in his stateroom as to what to do with his bags. Whittlesey’s cenotaph is located at Pittsfield Cemetery in his home town of Pittsfield, Massachusetts. It is an ‘IMO’ marker (In Memory Only). His body was never found.

In prepared remarks before a gathering at Abilene Christian College in 1938, Lieutenant James Leak compared those six days lost in the Ardennes with the 1836 siege of the Alamo, and the legendary 300, at Thermopylae. “[T]he “Lost Battalion””, he said, “is entirely a misnomer…it was not “Lost”. We knew exactly where we were, and went to the exact position to which we had been ordered“.

In 1825, Lick left Buenos Aires, for a year-long tour of Europe. This was the time of the Brazilian War for Independence, and Portuguese authorities captured his ship on its return.

In 1825, Lick left Buenos Aires, for a year-long tour of Europe. This was the time of the Brazilian War for Independence, and Portuguese authorities captured his ship on its return. Gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, shortly after Lick’s arrival. He caught a little of the gold fever himself, but soon learned that he could make more money buying and selling land, rather than digging holes in it.

Gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, shortly after Lick’s arrival. He caught a little of the gold fever himself, but soon learned that he could make more money buying and selling land, rather than digging holes in it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.